abhidhamma stages

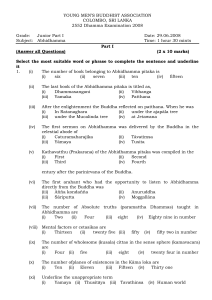

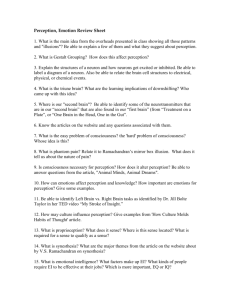

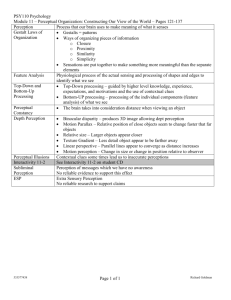

advertisement

Extract from Les Lancaster lecture on Stages of Perception. Equanimity is not only the prerequisite for further transformation, it is also central to the sharp observational skills that underpin the analysis of mental processes. My own approach to the nature of consciousness places considerable emphasis on these skills and their fruits, as depicted in the Abhidhamma texts. An understanding of the Abhidhamma’s analysis of the stages of perception can cast considerable light on the nature of the psychological processes. It enables me to take the first steps towards the integrative theory of consciousness that I shall develop in future chapters. The stages of perception in Abhidhamma The Abhidhamma states that in a complete perceptual process there are seventeen moments of consciousness, grouped into a number of stages. During the first three moments, the mind’s naturally pure state (bhavanga) is disturbed when a stimulus arrives at the ‘sense door’. Following this, there is a turning towards the particular sense door stimulated (moment four - ‘adverting’). In moment five, a sensory consciousness arises. In the case of visual perception, for example, this stage would be termed ‘seeing.’ Such ‘seeing’ is not what we normally mean by the term, for there is no recognition of the object at this stage. It is characterised by a sense of contact between sense organ and sense object, and might be thought of as a consciousness that merely intimates that a formed entity has stimulated the eye. ‘The subject sees a certain object, as to the nature of which it does not as yet know anything’ (Aung, 1910/1972, p. 28, emphasis original). Harvey (1995) suggests that there is a ‘bare awareness of a sensory object being present, plus the knowledge of which sensemodality it belongs to, and the discernment which discriminates the object into its basic parts or aspects’ (p. 150). The next three stages in the perceptual sequence—occupying moments six to eight— entail a more conceptual analysis of the input, by means of which the nature of the object giving rise to that input is clarified. The first of these stages is termed ‘receiving’, which may be understood as a receiving of the input by that faculty of mind which, in due course, will discriminate and cognize the sensory input. It is said to be characterised by a simple feeling tone, and may perhaps be best thought of as an initial sense of the ‘flavour’ conveyed by a given sense object, which at this stage is merely ‘agreeable,’ ‘disagreeable’ or ‘neutral’. ‘Receiving’ is followed in moment seven by ‘examining’. During this stage, the mind detects the marks of differentiation in the object. The function of sanna, ‘cognition’, is said to be strong during this stage. The linguistic element sa- implies ‘linking’, and the psychological function seems to entail an examination of the associations that the received entity give rise to. ‘Sanna is the activity of seeing-as: knowing something through the application of a specific perceptual label’ (Harvey, 1995, pp. 141-2). By means of the examination, the nature of the object is assessed, but, as yet, there is no reaction to it. For Guenther (no date), consciousness at this stage has the ‘nature of general inclusion’ (p. 39), and therefore mistakes can be made, such as when a deer mistakes a scarecrow for a man. We should understand ‘examining consciousness’ as the function whereby one detects features in common across associated images, a necessary preliminary to establishing the identity of the stimulus that triggered the process in the first place. The next stage—moment eight—is that of ‘establishing,’ which ‘determines the nature of the mind’s response to the object which has been identified’ (Cousins, 1981, p. 33). As Aung suggests, during this stage the definitive properties of the object are separated from the surroundings, in order that the object might finally be apperceived in the ensuing stage. ‘Establishing’ is described as the ‘gateway’ to further perceptual reactions, since it determines the precise bias which will become dominant in the continuation of the mental process. It is important to realise that at no stage, up to and including this one of ‘establishing’, is the subject ‘intelligently aware’ (Aung, 1910/1972, p. 29) of the nature and character of the object. From the moment of ‘adverting’ to that of ‘establishing’ the process is viewed as progressing automatically. By contrast, progress to the subsequent two stages is not inevitable, allowing for the possibility of so-called ‘incomplete’ cases, as indicated in Figure 3.2. The stages of perception in Abhidhamma The Abhidhamma states that in a complete perceptual process there are seventeen moments of consciousness, grouped into a number of stages. During the first three moments, the mind’s naturally pure state (bhavanga) is disturbed when a stimulus arrives at the ‘sense door’. Following this, there is a turning towards the particular sense door stimulated (moment four - ‘adverting’). In moment five, a sensory consciousness arises. In the case of visual perception, for example, this stage would be termed ‘seeing.’ Such ‘seeing’ is not what we normally mean by the term, for there is no recognition of the object at this stage. It is characterised by a sense of contact between sense organ and sense object, and might be thought of as a consciousness that merely intimates that a formed entity has stimulated the eye. ‘The subject sees a certain object, as to the nature of which it does not as yet know anything’ (Aung, 1910/1972, p. 28, emphasis original). Harvey (1995) suggests that there is a ‘bare awareness of a sensory object being present, plus the knowledge of which sensemodality it belongs to, and the discernment which discriminates the object into its basic parts or aspects’ (p. 150). The next three stages in the perceptual sequence—occupying moments six to eight— entail a more conceptual analysis of the input, by means of which the nature of the object giving rise to that input is clarified. The first of these stages is termed ‘receiving’, which may be understood as a receiving of the input by that faculty of mind which, in due course, will discriminate and cognize the sensory input. It is said to be characterised by a simple feeling tone, and may perhaps be best thought of as an initial sense of the ‘flavour’ conveyed by a given sense object, which at this stage is merely ‘agreeable,’ ‘disagreeable’ or ‘neutral’. ‘Receiving’ is followed in moment seven by ‘examining’. During this stage, the mind detects the marks of differentiation in the object. The function of sanna, ‘cognition’, is said to be strong during this stage. The linguistic element sa- implies ‘linking’, and the psychological function seems to entail an examination of the associations that the received entity give rise to. ‘Sanna is the activity of seeing-as: knowing something through the application of a specific perceptual label’ (Harvey, 1995, pp. 141-2). By means of the examination, the nature of the object is assessed, but, as yet, there is no reaction to it. For Guenther (no date), consciousness at this stage has the ‘nature of general inclusion’ (p. 39), and therefore mistakes can be made, such as when a deer mistakes a scarecrow for a man. We should understand ‘examining consciousness’ as the function whereby one detects features in common across associated images, a necessary preliminary to establishing the identity of the stimulus that triggered the process in the first place. The next stage—moment eight—is that of ‘establishing,’ which ‘determines the nature of the mind’s response to the object which has been identified’ (Cousins, 1981, p. 33). As Aung suggests, during this stage the definitive properties of the object are separated from the surroundings, in order that the object might finally be apperceived in the ensuing stage. ‘Establishing’ is described as the ‘gateway’ to further perceptual reactions, since it determines the precise bias which will become dominant in the continuation of the mental process. It is important to realise that at no stage, up to and including this one of ‘establishing’, is the subject ‘intelligently aware’ (Aung, 1910/1972, p. 29) of the nature and character of the object. From the moment of ‘adverting’ to that of ‘establishing’ the process is viewed as progressing automatically. By contrast, progress to the subsequent two stages is not inevitable, allowing for the possibility of so-called ‘incomplete’ cases, as indicated in Figure 3.2. [Insert Figure 3.2 about here] The next stage is referred to by the Pali term, javana, which means ‘running.’ I will follow Rhys Davids in using this term untranslated, since no single English word adequately conveys its meaning. Terms such as ‘apperception’ and ‘impulsions’ are often used, but are obscure. The term is evidently intended to convey the more active nature of the mind process engaged at this point. In fact, the javana thought-process generally runs for seven moments of consciousness. The previous stage of ‘establishing’ is said to be characterised by a strong presence of drive. It is within the javana phase that this drive is consummated, and implicates potential actions likely to have future karmic consequences. In a useful analogy to the intake of food, ‘establishing’ is equated to smelling the food, whilst javana is the act of actually eating the food. Javana brings about the individual’s conceptualization of the event or stimulus which began the process. ‘At this stage ... the subject interprets the sensory impression, and fully appreciates the objective significance of his experience’ (Aung, 1910/1972, p. 29). Javana is a critical stage for the individual’s spiritual development, since it has the potential to lock in place habitual, ‘unskilful’ ways of perceiving and thinking. Buddhism calls on the individual to overcome such limitations in perception and thought. Moreover, in the unenlightened person, javana generates the sense of self as apparent subject of the perception, resulting in what to Buddhism is the ‘conceit of “I am”’ (Collins, 1982, p. 242). According to the Abhidhamma, the perceptual process is completed with two final moments of ‘registering’. Collins suggests that, ‘In modern terms, perhaps, one might interpret these two moments as the transition from a perception to the (short-term) memory of it; a transition necessary if the event is to be stored in (long-term) memory’ (Collins, 1982, p. 243). Cousins points out that the precise meaning of the Pali term used here (Tadarammana) is ‘having the same object’ and that the stage, ‘may perhaps be seen as fixing the conscious experience of the javana stage in the unconscious mind’ (Cousins, 1981, p. 28). The notion of the whole javana reaction, including the sense of ‘I’ (in the spiritually undeveloped person) becoming fixed in memory, is a point of some importance. This notion will be discussed later in terms of the role of ‘I’ in memory (see Chapter 5). For the moment, let us simply note that the sense of self experienced at the time of perception is viewed as being stored together with the trace of whatever may have been perceived. The function of each stage in the process is illustrated by various extended similes, an example being the following. A man is sleeping under a mango tree, with his head covered (moment one). The wind rustles the branches, causing a mango-fruit to fall, grazing the sleeping man’s ear (moments two and three). He is aroused from sleep by the sound (moment four— ‘adverting’); removes his head covering and looks (moment five—‘sensation’); picks up the mango (moment six—‘receiving’); examines it by squeezing it (moment seven); and recognizes it as a mango by smelling it (moment eight—‘establishing’). He eats it (moments nine to fifteen—javana); and savours the last morsels and the after-taste (moments sixteen and seventeen— ‘registering’). In addition to its description of the complete perceptual process, attributable to what is called a ‘very great object’, the Abhidhamma considers various incomplete cases, in which the process fails to reach moment seventeen. Three such cases are recognized (see Figure 3.2), two of which may be equated with known psychological conditions. The incomplete case labelled by the Abhidhamma as ‘great’, in which there is a failure to register the javana stage, would seem to relate directly to cases of amnesia. Here, there is no deficiency in perception per se, but subsequent memory for what has been perceived is compromised. The ‘slight’ case, which ends when the object is established, may be related to phenomena such as subliminal perception. Despite the nature of the sensory stimulus being established, it does not become incorporated into the normal conscious process dominated by the sense of ‘I’. These postulated parallels to cases studied by cognitive neuroscience will be revisited in later chapters. For the moment, let me emphasize that the consciousness associated with the arising of ‘I’ (in Abhidhamma terms, arising through the javana moments in an untrained mind) should not be seen as the totality of consciousness. Material that may be inaccessible to ‘I’, and subliminal in such terms, may not intrinsically be outside of consciousness. The next stage is referred to by the Pali term, javana, which means ‘running.’ I will follow Rhys Davids in using this term untranslated, since no single English word adequately conveys its meaning. Terms such as ‘apperception’ and ‘impulsions’ are often used, but are obscure. The term is evidently intended to convey the more active nature of the mind process engaged at this point. In fact, the javana thought-process generally runs for seven moments of consciousness. The previous stage of ‘establishing’ is said to be characterised by a strong presence of drive. It is within the javana phase that this drive is consummated, and implicates potential actions likely to have future karmic consequences. In a useful analogy to the intake of food, ‘establishing’ is equated to smelling the food, whilst javana is the act of actually eating the food. Javana brings about the individual’s conceptualization of the event or stimulus which began the process. ‘At this stage ... the subject interprets the sensory impression, and fully appreciates the objective significance of his experience’ (Aung, 1910/1972, p. 29). Javana is a critical stage for the individual’s spiritual development, since it has the potential to lock in place habitual, ‘unskilful’ ways of perceiving and thinking. Buddhism calls on the individual to overcome such limitations in perception and thought. Moreover, in the unenlightened person, javana generates the sense of self as apparent subject of the perception, resulting in what to Buddhism is the ‘conceit of “I am”’ (Collins, 1982, p. 242). According to the Abhidhamma, the perceptual process is completed with two final moments of ‘registering’. Collins suggests that, ‘In modern terms, perhaps, one might interpret these two moments as the transition from a perception to the (short-term) memory of it; a transition necessary if the event is to be stored in (long-term) memory’ (Collins, 1982, p. 243). Cousins points out that the precise meaning of the Pali term used here (Tadarammana) is ‘having the same object’ and that the stage, ‘may perhaps be seen as fixing the conscious experience of the javana stage in the unconscious mind’ (Cousins, 1981, p. 28). The notion of the whole javana reaction, including the sense of ‘I’ (in the spiritually undeveloped person) becoming fixed in memory, is a point of some importance. This notion will be discussed later in terms of the role of ‘I’ in memory (see Chapter 5). For the moment, let us simply note that the sense of self experienced at the time of perception is viewed as being stored together with the trace of whatever may have been perceived. The function of each stage in the process is illustrated by various extended similes, an example being the following. A man is sleeping under a mango tree, with his head covered (moment one). The wind rustles the branches, causing a mango-fruit to fall, grazing the sleeping man’s ear (moments two and three). He is aroused from sleep by the sound (moment four— ‘adverting’); removes his head covering and looks (moment five—‘sensation’); picks up the mango (moment six—‘receiving’); examines it by squeezing it (moment seven); and recognizes it as a mango by smelling it (moment eight—‘establishing’). He eats it (moments nine to fifteen—javana); and savours the last morsels and the after-taste (moments sixteen and seventeen— ‘registering’). In addition to its description of the complete perceptual process, attributable to what is called a ‘very great object’, the Abhidhamma considers various incomplete cases, in which the process fails to reach moment seventeen. Three such cases are recognized (see Figure 3.2), two of which may be equated with known psychological conditions. The incomplete case labelled by the Abhidhamma as ‘great’, in which there is a failure to register the javana stage, would seem to relate directly to cases of amnesia. Here, there is no deficiency in perception per se, but subsequent memory for what has been perceived is compromised. The ‘slight’ case, which ends when the object is established, may be related to phenomena such as subliminal perception. Despite the nature of the sensory stimulus being established, it does not become incorporated into the normal conscious process dominated by the sense of ‘I’. These postulated parallels to cases studied by cognitive neuroscience will be revisited in later chapters. For the moment, let me emphasize that the consciousness associated with the arising of ‘I’ (in Abhidhamma terms, arising through the javana moments in an untrained mind) should not be seen as the totality of consciousness. Material that may be inaccessible to ‘I’, and subliminal in such terms, may not intrinsically be outside of consciousness.