Results and Discussion - Center for Behavioral Decision Research

advertisement

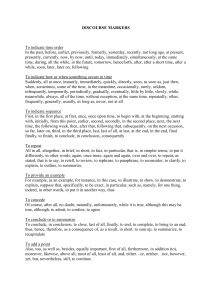

Delay, Doubt, and Decision: How Delaying a Choice Reduces the Appeal of Normative Options Niels van de Ven Tilburg University Thomas Gilovich Cornell University Marcel Zeelenberg Tilburg University Running Head: Delay, Doubt, and Decision Key words: Status Quo; Default; Decision Making; Delayed Choice 2 Abstract To help explain a regularity in democratic elections, we examined whether choosing to delay making a choice between a normative option and an alternative tends to make people subsequently less likely to choose what most people would otherwise have chosen. The results of two experiments demonstrated that participants who chose to put off making a decision between two alternatives were indeed less likely to opt for the normative option. Two additional experiments that primed a sense of doubt in participants provided support for a self-perception account of this result. Electing to delay making a choice is interpreted as an indication of doubt—doubt that tends to be attributed to the most prominent option, which is typically the normative option. Delayinduced doubt about the normative option makes it less appealing and less likely to be selected. 3 Delay, Doubt, and Decision: How to Undo the Appeal of Normative Options Half of the electorate was disappointed by the outcome of the 2004 U.S. Presidential contest. Furthermore, because losing tends to elicit more pain than winning elicits pleasure (Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, & Vohs, 2001; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Rozin & Royzmann, 2001), we can assume—and the blogosphere appeared to confirm—that supporters of John Kerry had stronger emotional reactions to the outcome than did supporters of George W. Bush. In addition to the conviction that the outcome meant that the country would continue down the wrong path, Kerry supporters had an additional reason to be disappointed: Most pollsters predicted that Kerry would win. Why did so many polls get it wrong? It appears that most pollsters factored in a statistical regularity known as the incumbent rule that, alas, did not play out in this particular election. The incumbent rule describes the fact that undecided voters who end up casting ballots tend to vote against the incumbent. One analysis found that in 127 of 155 national, state, and municipal elections, the majority of undecided voters went for the challenger (Panagakis, 1989). Had most of the 3.5 million voters who described themselves as undecided near the end of the 2004 campaign voted for John Kerry, George Bush would have been a one-term president (CNN/USA Today/Gallop, 2004). They did not do so in this election, perhaps because the anxiety aroused in the electorate in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks made the prospect of change—and its attendant uncertainty—unappealing (see Landau, Solomon, Greenberg, Cohen, & Pyszczynski, 2004; Lerner, Gonzalez, Small, & Fischhoff, 2003; Willer, 2004). 4 Whatever psychologists may think of the outcome of the 2004 election, they are likely to find the very existence of the incumbent rule of some interest. Why do undecided voters tend to vote against the incumbent? One might have expected undecided voters to do the opposite. After all, decision researchers have documented a pervasive status quo bias in people’s choices—when in doubt, people tend to stick with the status quo option rather than try something new (Ritov & Baron, 1992; Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988). Undecided voters are nothing if not in doubt, and the incumbent is by definition the status quo candidate. Why, then, don’t undecided voters favor the incumbent? One possibility is that the status quo bias may typically exert itself before the eve of the election, and therefore at that point the remaining undecided voters are people who couldn’t quite get themselves to favor the incumbent despite the status quo bias. Undecided voters, in other words, may be mainly undecided about—i.e., have reservations about—the incumbent (Panagakis, 1989). Thus, when the time comes to cast their ballots, the doubts these voters harbor about the incumbent exert themselves and they tend to vote for the challenger. In this article, we propose and test a variant of this explanation and examine its broader implications. We contend that undecided voters interpret the fact that they have yet to decide as information that calls the incumbent into question. Given that the incumbent is typically the more psychologically prominent of the candidates, and given that people have an understanding of the idea that “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” they may wonder why they haven’t already resolved to vote for the incumbent. “If the 5 incumbent is so great, why am I having reservations about voting for him?” The experience of doubt, in other words, is experienced as doubt about the incumbent. This analysis implies that a similar effect should manifest itself far beyond democratic elections. That is, the doubt that comes with the decision to delay making a choice will typically be attributed to the most psychologically prominent option, and thus reduce its appeal. Thus, normative options of all sorts—options that most people would otherwise favor if not for a delay—should prove less popular after putting off a decision.1 People tend to prefer a sure thing over a gamble with only a slightly higher expected value and so this analysis leads to the prediction that the gamble may seem more attractive after a delay. People typically prefer the status quo (Ritov & Baron, 1992; Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988) and default options (Johnson & Goldstein, 2003) over their alternatives and so this analysis leads to the prediction that the alternative may be more appealing after a delay. A key element of our analysis is that the delay is selfchosen: A delay that is imposed cannot be taken as a sign of one’s doubts about the incumbent and thus, we predict, would not have the same effect (Bem, 1972). A rather different effect of delay on choice was reported by Bastardi and Shafir (1998). They found that people often wait to learn additional information that, if they had known about it from the start, would not have influenced their decision. But because they chose to wait for it, once it arrives, it has an impact. They give the example of a student who is thinking about enrolling in a course, but doesn’t know whether it will be taught by a renowned lecturer or a replacement. Had it been known from the beginning that it would be taught by the replacement, the student would likely have enrolled anyway. But because uncertainty is something one tries to avoid and the costs of waiting 6 are minimal, the student might very well wait to find out who is teaching the course. If, at that point, it is discovered that the course will be taught by the replacement, the student might very well choose not to enroll. (“If I waited to find out who was teaching the course, it must matter to me, and so the fact that it is not taught by the right teacher must mean that it is not the right course for me.”) In the research reported by Bastardi and Shafir (1998), the delay and subsequent receipt of additional information led participants to make a different decision than they would have made otherwise. Our research investigates whether the mere decision to wait, without the subsequent receipt of any additional information, can also lead people to make a different decision than they would have made otherwise—to reject the normative option rather then embrace it. In Bastardi and Shafir’s studies, participants apparently inferred from their decision to await additional information that the information was instrumental to their choice. In our research, we examine whether participants will attribute their delay to doubts about the most salient or normative option. We report the results of four studies that examine our thesis. Experiment 1 examines whether choosing to delay making a choice leads people ultimately to be less inclined to choose the normative option than when the choice is made right away. Experiment 2 investigates the same question, but does so in a situation in which the choice has real consequences for participants and also compares the effect of a selfchosen delay with an imposed delay. Experiments 3 and 4 examine the mechanism underlying the results obtained in the first two studies. More specifically, these latter two studies examine whether an induced sense of doubt tends to be attributed to the most prominent option and hence leads people to be disinclined to choose it. 7 Experiment 1 Participants were asked to put themselves in the position of someone who had inherited money from a relative, with the stipulation that the money had to be invested, and could not be spent, for five years. The relative’s financial advisor recommended that the money be invested in the stock of one company, but mentioned the stock of another company as a possible alternative. The key question was whether, when asked to choose, participants would opt for the first, default, option or the alternative.2 Half the participants were shown the daily stock prices of the two stocks for the previous three months and were asked to make their decision. The other half were asked if they would like to wait and see the daily stock prices of the two companies over the next three months before making a decision. Both groups of participants received the same threemonths’ record of performance, which provided no basis for favoring one stock over the other. We predicted that those who elected to wait before making a decision would be less likely to choose the default option than those who had to choose immediately. Method Participants. Sixty-four Cornell University undergraduates participated in exchange for extra credit in their psychology or human development courses. Procedure. Participants read a scenario inviting them to imagine that an uncle left them a substantial inheritance that they could not spend for at least five years. The family’s financial advisor recommended that the money be invested in Bank of America stock in the interim. The advisor also stipulated that if there were any objection to investing in Bank of America, an alternative would be to invest the inheritance in United 8 Technologies, whose stock had “performed on par with that of Bank of America stock for the last several years.” Participants in the immediate choice condition were shown a graph depicting the performance of both stocks over the previous three months. As can be seen in Figure 1, the (hypothetical) performance of the two stocks during this period was very similar and offered no compelling basis for choosing one over the other. Participants were asked whether they would “take the financial adviser’s recommendation and invest in Bank of America” or “invest in United Technologies.” Participants in the possible delay condition, who were not initially shown a graph of the stocks’ three-month performance, were asked whether they wanted to choose between the two stocks right then or put off the decision until they completed other, unrelated studies, after which time they would receive information about the performance of the two stocks over the past three months. After spending roughly fifteen minutes completing the unrelated experiments, participants who had chosen to put off their decision were then shown the graph of the two stocks’ performance and asked to make their choice. Results & Discussion Consistent with prior research (Dhar & Simonson, 1992; Ritov & Baron, 1992; Samuelson & Zeckhauser, 1988), the overwhelming majority (84%) of participants in the immediate choice condition opted for the focal option, to invest in Bank of America. As predicted, a significantly smaller percentage of participants (62%) who were given the opportunity to delay their decision chose the recommended option, χ2(1, N = 64) = 3.93, p < .05. 9 This comparison, although statistically significant, likely understates the true effect of delaying a choice. Nine of the 32 participants in the possible delay condition did not delay their decision and they all chose to invest in Bank of America. Among the remaining 23 participants who opted to delay making a choice, only 48% chose to invest in Bank of America, the focal option. The choice of participants who actually delayed their choice differed from those who could delay but did not, χ2(1, N = 32) = 7.51, p < .01, and from those who were asked to choose immediately, χ2(1, N = 55) = 8.37, p < .01. These latter groups did not differ from each other, p = .568, Fisher’s exact test.3 The results of this study indicate that a delay in making a choice can influence the choice that is eventually made, even if the delay does not result in the acquisition of additional information that could be taken to favor one option over another. Participants who elected to delay their choice were less likely to choose the default option. These results are thus both consistent with, and yet quite different from, those of Bastardi and Shafir (1998), who found that that people often put off a decision in order to receive information that, had they known it from the beginning, would not have influenced their choice. But, having waited to receive the information, they alter their decision to be in line with it. In their studies, the information received favored one option over the other. In the current study, it was the delay itself that influenced participants’ choices. Experiment 2 To further test our contention that electing to delay a choice makes one less likely to opt for the normative option, we conducted an experiment that expands on the results of Experiment 1 in three important respects. First, the choice that was put to participants was not hypothetical, but involved real financial consequences. Second, to test the idea 10 that it is the knowledge that one chose to wait that is responsible for the effect documented in Study 1, we added a condition in which participants were forced to wait before making their choice. We predicted that these participants would opt for the normative option just as often as those in the control condition. Third, to test the generality of the phenomenon under investigation, we also operationalized the status quo in a very different fashion from Experiment 1. In this case, we had participants choose between a guaranteed sum of money, on the one hand, and a chance of getting a larger sum, on the other. Because the expected value of the gamble was not much higher than the guaranteed sum, we expected the latter to serve as a powerful default option from which, under normal circumstances, few participants would depart. Method Participants. Sixty-one Cornell University undergraduates participated in exchange for extra credit in various Psychology and Human Development courses. Procedure. The experimenter explained to each participant that he or she would complete two separate experiments. The first, a study of everyday decision making, involved a simple choice: whether to receive $5 for certain or opt for a 70% chance of receiving $8. Participants were shown a cup with 7 white stones and 3 black stones from the game of Go and told that, if they elected to gamble, they would draw blindly from the cup and receive $8 if they drew a white stone and nothing if they drew a black stone. Participants in the immediate choice condition made the choice right away and then proceeded to the second, entirely unrelated study. Participants in the chosen delay condition were told that they could make the decision right away or wait until the completion of the other study (which involved a get- 11 acquainted conversation with another participant and was completely unrelated to this experiment). The experimenter explained that it would be a bit more convenient for her if the choice were delayed but that the timing of the decision was entirely up to the participant. Participants were then given a sheet of paper and asked to place a checkmark next to “I choose to decide now” (n=1) or “I choose to decide later” (n=19). Having participants write down their preference was designed to reinforce the fact that they had chosen to delay the decision. Participants in the forced delay condition were told about the choice between $5 for sure or a 70% chance of $8, but were also told that they would be making their decision at the end of the session, after the other experiment was completed. Results and Discussion As predicted, and as shown in Figure 2, participants who chose to delay making their decision were less likely to opt for the sure amount (53%) than were participants who either had to make the choice right way (70%) or had to delay making the choice (86%). As predicted, the pattern of responses in the latter two conditions did not differ significantly, χ2 (1, N = 41) = 1.48, but they did differ from the responses of the nineteen participants in the chosen delay condition who, in fact, chose to put off their decision, χ2 (1, N = 60) = 3.99, p < .05). When the single participant in the chosen delay condition who did not put off the decision (and who, not surprisingly, opted for the sure amount) is included in the analysis, this difference was only marginally significant, χ2 (1, N = 61) = 3.43, p < .10). Experiment 3 12 We have offered something of a self-perception account of the tendency of people who delay making a choice to reject the normative option, operationalized in one study as the default and in another as a sure thing. Those who decline the opportunity to decide have observed a behavior they need to explain: their own failure to choose. The failure to make a choice is likely to be taken as a signal that one is in doubt, doubt that is likely to be attributed disproportionately to the most prominent alternative, which, in most cases, is the normative option. Failing to make a choice that could have been made calls into question all available options, but the normative option particularly strongly (Simmons & Nelson, 2006). Individuals are likely to reason, explicitly or implicitly, “Why don’t I feel comfortable with this [the normative] option? There must be something wrong with it.” To test this interpretation of the results obtained in Studies 1 and 2, we used a priming procedure to activate a sense of doubt in our participants. We predicted that this incidental feeling of doubt would tend to be attributed to the most prominent option, which, in the context of this experiment, would likely be the status quo option for most participants. We therefore anticipated that participants in whom the concept of doubt had been primed would be less likely than those in a control condition to choose the status quo option. Method Participants. Eighty Tilburg University students completed this experiment as part of a larger research session for which they received course credit. Procedure. All participants first completed a scrambled sentence task (Bargh, Chaiken, Raymond, & Hymes, 1996; Srull & Wyer, 1979). This task was introduced as a language skills study being conducted for the Department of Communication and one that 13 was unrelated to the other tasks performed in the testing session. This cover story was reinforced by the use of different logos and layouts on the response forms. More specifically, they were given a series of sets of words from which they were to construct grammatically correct sentences. In the neutral condition they unscrambled 20 sets of words that did not revolve around a single theme. In the doubt condition, participants also unscrambled 20 word sets, 10 of which were related to the theme of doubt. Participants in the doubt condition, for example, were given the set “did know not to John what do”, which could be unscrambled to create “John did not know what to do”. After writing down 10 sentences related to the theme of doubt and uncertainty, we expected the concept of doubt to be activated in the minds of participants in the doubt condition. A comprehensive debriefing revealed that none of the participants in the doubt condition was aware that many of the sentences were related to the theme of doubt. After completing the scrambled sentence task, participants read a scenario that required them to make a hypothetical choice. The scenario was based on one used by Samuelson and Zeckhauser (1988) in one of the landmark studies of the status quo effect. Participants were asked to imagine that they worked for a company and had to choose one of four offers to make to a potential customer. They could choose one offer that would result in a €15,000 profit, with a 70% chance that the offer would be accepted; a second possible offer would result in a €20,000 profit, with a 60% chance of acceptance; a third would result in a €25,000 profit, with a 50% chance of acceptance; and the fourth would result in a €30,000 profit, with a 40% chance of acceptance. Half the participants were presented with the first option specified as the default (“the normal policy of the 14 company is to ask for €15,000”). For the remaining participants, none of the options was singled out. The design was thus a 2 (Prime: Neutral versus Doubt) 2 (Framing: Status Quo provided versus not provided) between-participants factorial, with participants equally distributed among the conditions. Results & Discussion As predicted, and as shown in Table 1, the usual status quo effect was exhibited by participants in the status quo condition. These participants chose to make the €15,000 offer significantly more often when it was presented as the status quo (75%) than when it was listed simply as one of the four options (20%), χ2(1, N = 40) = 12.13, p < .001. However, no such effect was observed among participants primed with doubt, who chose to make the €15,000 offer roughly equally often when it was presented as the status quo (40%) and when it was not (30%), χ2(1, N = 40) = 0.44, p > .5. Examining these two effects in one overall analysis, the effect of framing the €15,000 offer as the status quo or not exerted a significantly larger effect on participants in the neutral condition than it did on participants in the doubt condition, Wald z =2.02, p <.05. Perhaps most important, the percentage of participants who chose the status quo option was significantly higher in the neutral prime condition (75%) than in the doubt prime condition (40%), χ2(1, N = 40) = 5.02, p < .05. These findings indicate that activating the concept of doubt can erase the status quo effect. We attribute this result to the tendency of people to construe their feelings of doubt as doubt about the most salient option. In this case, the option highlighted as the status quo was almost certainly the most prominent to all participants because there was 15 little else to distinguish the four options. To further investigate whether it is the tendency to attach one’s feeling of doubt to the most salient option that is responsible for the observed tendency to shy away from a normative option, we employed a more direct manipulation of salience in the following study. Also, to provide further evidence that it is the attribution of doubt to the most salient option that is responsible for the observed effects, the following study also includes a manipulation check to be sure that the scrambled sentence task did indeed increase the feeling of doubt. Experiment 4 In this study, we manipulated the relative salience of different options by making one option the focal option. That is, before making a choice between two consumer products, we had participants take some time to think about one product or the other, hence making it focal. Prior research has shown that people tend to prefer focal options over non-focal options (Dhar & Simonson, 1992). We expected no such preference among participants primed with doubt. We expected these participants to attribute their feeling of doubt to the focal option and therefore see it as less desirable. Method Participants. One hundred twenty Tilburg University students participated in exchange for course credit. Procedure. Participants first completed the same scrambled sentence task used in Experiment 3, half in the neutral condition and half in the doubt condition. Participants then read a brief scenario that asked them to imagine that they were interested in buying a flat-panel television. The choice set consisted of two options, one from Samsung and one from Sony. Following Dhar and Simonson (1992), participants were asked to write down 16 one advantage and one disadvantage of either Samsung (Samsung focal condition) or Sony (Sony focal condition). Participants were not given any detailed information about a particular Sony or Samsung model, but both are well-known brands and every participant was able to list an advantage and disadvantage of the focal brand. What they listed, not surprisingly, was rather general and non-descript (e.g., “Sony is well known for quality sound players”; “Samsung is generally good quality, but expensive”). After providing the requested information, participants were asked to rate how difficult it was for them to specify an advantage and disadvantage of the specified product on an 11-point scale anchored at “very difficult” (-5) and “very easy” (5). Participants in a control group were not asked to think of an advantage or disadvantage of either product (and hence did not rate the difficulty of doing so). All participants indicated their preference for one of the two televisions by checking the relevant point on an 11-point scale, with Samsung on one endpoint and Sony on the other. The position of the two brands at the scale endpoints was counterbalanced (and had no influence on the results). The design was thus a 2 (Prime: neutral versus doubt) 3 (Focal Option: Samsung versus Sony focal versus none) factorial. Results and Discussion Manipulation check. As a check on the effectiveness of the doubt prime, we examined participants’ ratings of how difficult it was for them to list a positive and negative feature of the specified brand. This question was not asked of participants in the control condition and so only the data from those in the Sony focal and Samsung focal conditions were used in this analysis. A 2 (Prime: neutral versus doubt) 2 (Focal Option: Samsung versus Sony) ANOVA yielded only one significant result, the predicted 17 main effect of prime, F(1, 73) = 5.60, p < .05. Participants who were primed with doubt found it more difficult to report a positive and a negative attribute (-0.82) than did those in the neutral prime condition (0.97). The priming manipulation thus appears to have been effective. Brand preference. A 2 (Prime: neutral versus doubt) 3 (Focal Option: Samsung versus Sony versus none) ANOVA yielded only one significant effect, the predicted interaction between prime and focal option, F(2, 114) = 4.41, p < .05. As can be seen in Figure 3, participants tended to favor the focal option after they had unscrambled neutral sentences: those for whom Samsung was the focal option tended to favor the Samsung more than those for whom the Sony was the focal option, although not to a statistically significant degree, t(144) = 1.58, p = .12. A stronger pattern of preferences in the opposite direction was expressed by participants in the doubt prime condition: Those for whom the Samsung was the focal option had less of a preference for the Samsung than those for whom the Sony was the focal option, t(144) = 2.62, p = .01. In the control condition, the priming manipulation, as expected, had no effect on participants’ preference, t(114) = 0.45, p = .653. In the most direct test of our hypothesis, we collapsed (with appropriate reverse scoring) the two conditions in which one option was made focal and found a significant difference between priming condition, t(114) = 2.97, p < .01. Participants in the neutral prime condition preferred the focal option (M = 0.73, with higher numbers indicating a preference for the focal option) significantly more than did those in the doubt prime condition (M = -1.20). These findings demonstrate that an increase in doubt can undermine the usual preference for focal options. Participants primed with doubt exhibited a preference for the 18 non-focal option over the focal option. That an incidental feeling of doubt tends to influence choice in the same way as a delay of a choice supports our contention that it is the attribution of doubt to the most salient option that is responsible for the effect that choosing to delay a choice has on the choice itself. General Discussion The studies presented here demonstrate that both delay and the activation of doubt influence choice in a consistent way. Experiments 1 and 2 demonstrate that a voluntary delay in making a choice leads people to select the normative option less often. Participants who delayed making a choice in Experiment 1 were less likely to select a recommended option. Those who chose to delay their choice in Experiment 2 were less likely to opt for a sure gain over a gamble. Experiments 3 and 4 demonstrated that the activation of doubt has the same effect, leading people to select a normative or focal option less often as well. Together, the results of these studies suggest that electing to delay making a choice is taken as a sign of doubt about the best option to choose, a state that tends to be attributed disproportionately to the normative or focal option. As a result, the normative option is chosen less often than it would have been otherwise. We noted earlier that this research was inspired by a curious regularity in electoral history—that undecided voters who end up casting ballots tend not to vote for the incumbent. This regularity is curious because one might very well have expected the opposite result. Undecided voters are, by definition, uncertain and one might expect them to deal with their uncertainty by clinging to the familiar candidate (the incumbent) and rejecting the unfamiliar candidate (the challenger). Our findings help to make sense of this curiosity, but also highlight a more general version of the same puzzle. That is, 19 why doesn’t the sense of doubt that is bound up in delaying a choice—or that arises from the direct activation of doubt itself—lead people to be more cautious and stick with what is often seen as the safer, normative alternative, such as the status quo, the default, or the sure thing? Our answer to this question is that the normative option is typically the most prominent or focal option, and hence the most salient “target” to which one’s sense of doubt can be attributed. But is that always the case? Aren’t there times when a sense of doubt makes people more conservative in their choices and more likely to opt for the normative option? Although only future research can answer this question for certain, we believe there are such circumstances, and a couple of candidates stand out. One obvious consideration that follows directly from our analysis is that the pattern of results might be very different when there is little difference in the psychological prominence of the different options. This might occur when the normative option is not more salient than the alternative, as might happen when the normative option is a rather mundane status quo option and the alternative has something thrilling about it. In such cases, a person’s sense of doubt may not be disproportionately attached to the normative option and hence it may not be disproportionately avoided. Another consideration that is likely to be important is the magnitude of the consequences associated with one’s choice. The more consequential the decision, the less likely people may be to stray from the “safety” of the normative option (Miller & Taylor, 1995; Risen & Gilovich, 2007a, 2007b). Even though the processes we have investigated in the research reported here may lead to doubts about the normative option, there are times when those doubts may not be strong enough to overcome the fear that 20 arises from the prospect of deviating from the safety of what most people would otherwise choose. The same can be said about accountability. The more accountable a person is for a given decision (Tetlock, 1992; Tetlock & Boettger, 1994), the less likely that person might be to stray from the status quo, a default option, or a focal option, even when he or she harbors doubts about such an option. The current findings are consistent with and extend recent work by Simmons and Nelson (2006) on how people choose between “intuitive” and non-intuitive options. Their work deals with those situations in which one has an intuitive, “gut” feeling that one option is best, but that feeling is opposed by various deliberate, “rational” considerations. They find that an increased feeling of confidence, even one induced from ancillary sources, makes people more likely to go with their gut feeling. For example, they find a pervasive tendency in sports betting contexts for people to bet on the favorite against the point spread (because their strong feeling that the favorite will simply win the game carries over to the more challenging bet against the spread). However, when participants were given a description of an upcoming game in a difficult-to-read font, they were less confident in their assessments and chose the favorite less often. What we have shown here is that delaying a choice that one could have made earlier is seen as a cue that one is not confident of which alternative is best (Bem, 1972). That lack of confidence, in turn, makes people less likely to choose, in Simmons and Nelson’s terminology, the “intuitive option”—the sure thing, the status quo, the most prominent option. The present research extends the work of Bastardi and Shafir (1998), who also documented how a delay in making a choice can systematically influence the choice that 21 is ultimately made. In their research, the delay was accompanied by additional information—information that, had it been known from the outset, would not have influenced a person’s decision. But, having waited to receive it, people feel compelled to take it into account and they end up choosing differently than they would have otherwise. Our research shows that the mere act of delaying a choice—without the receipt of additional information—can also systematically influence the options that are chosen, leading individuals veer away from prominent alternatives that they would otherwise have chosen. Some of the prominent alternatives that we examined could be characterized as defaults—as people’s “fall back” positions or what they would tend to choose unless something unusual occurred to make them choose otherwise. These might be described as “soft” defaults: not choices that would be enacted unless one chose otherwise (Johnson & Goldstein, 2003), but general preferences or tendencies, all else being equal, to make one choice rather than another. We found that delaying a choice makes people less inclined to go with such soft defaults. Would our effect also be obtained on “harder” defaults? Only further research can tell, of course, but there is every reason to suspect that it would be much harder to get people to turn away from firmer defaults. For one thing, the doubt that comes from delaying a choice might simply discourage people from making an active decision at all. Doing so would result in the default being “chosen” even if the delay fostered considerable doubt about it. Implications for the Quality of Decisions Folk wisdom advises us to “not rush to judgment,” to “think things over,” and even to “sleep on it” before making important decisions, advice that people readily take 22 to heart (Greenleaf & Lehman, 1995; Tykocinski & Ruffle, 2003). Whether this is good advice, of course, depends on what the decision maker does with the extra time. To the extent that additional pertinent information is gathered, the quality of decisions delayed will, on average, be enhanced (but see Bastardi & Shafir, 1998, for an exception). Without additional information, however, whether additional thought and analysis typically improves decision making is a question of great controversy (Carmon, Wertenbroch, & Zeelenberg, 2003; Dijksterhuis, 2004; Hammond, 1996; Payne, Bettman & Johnson, 1993) and likely depends on the decision domain in question and the analytic skills of the decision maker. The current findings suggest that beyond any substantive considerations that arise as a product of additional deliberation, choosing to delay a decision has a systematic effect on choice. One might consider this a good thing, given that what we have shown here is that after a delay people are less enamored of focal options and less inclined to go with the status quo. Indeed, when the status quo is arbitrary or when the focal option would otherwise be mindlessly followed, the effect of delaying a choice will, on average, be positive. But normative options like defaults or the status quo are often normative for a reason. They often represent the voice of experience and the accumulation of wisdom. Therefore, a tendency to depart from normative options may, in many of these circumstances, lead to decisions of lower average quality than those would ordinarily make. Thus, there may be no overall answer to the question of whether the effects and processes we report here tend to help or hinder effective decision making. The clearest prescriptive implication, then, is that decision makers be aware that the decision to delay 23 making a choice is not a neutral act: it alters the choices they are likely to make in a predictable direction. This fact constitutes potentially useful information that should be factored into decision analyses. Although polls now suggest that an even greater percentage of the American electorate now wishes that undecided voters in the 2004 Presidential election had conformed to historical trends and voted against the incumbent, the tendency for delayed choices to diminish the appeal of normative options like the status quo cannot be taken to be good or bad in itself. 24 References Bastardi, A., & Shafir, E. (1998). On the pursuit and misuse of useless information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 19-32. Bem, D. J. (1972). Self perception theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 1-62). New York: Academic Press. Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5, 323-370. Carmon, Z., Wertenbroch, K., & Zeelenberg, M. (2003). Option attachment: When deliberating making choosing feels like losing. Journal of Consumer Research, 30, 15-29. CNN/USA Today/Gallup. (2004). Final poll shows presidential race to be dead heat. Retrieved april 15th, 2005, from http://www.gallup.com/poll/content/login.aspx?ci=13873 Dhar, R., & Simonson, I. (1992). The effect of the focus of comparison on consumer preferences. Journal of Marketing Research, 29, 430-440. Dijksterhuis, A. (2004). Think different: The merits of unconscious thought in preference development and decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 586-598. Greenleaf, E. A., & Lehman, D. R. (1995). Reasons for substantial delay in consumer decision-making. Journal of Consumer Research, 22, 186-199. Hammond, K. R. (1996). Human judgment and social policy: Irreducible uncertainty, inevitable error, unavoidable injustice. New York: Oxford University Press. Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302, 1338-1339. 25 Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263-291. Landau, M. J., Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., Cohen, F., & Pyszczynski, T. (2004). Deliver us from evil: The effects of mortality salience and reminders of 9/11 on support for President George W. Bush. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1136-1150. Lerner, J. S., Gonzalez, R. M., Small, D. A., & Fischhoff, B. (2003). Effects of fear and anger on perceived risks of terrorism: A national field experiment. Psychological Science, 14, 144-150. Miller, D. T., & Taylor, B. R. (1995). Counterfactual thought, regret, and superstition: How to avoid kicking yourself. In N. J. Roese & J. M. Olson (Eds.), What might have been: The social psychology of counterfactual thinking (pp. 305-332). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Panagakis, N. (1989). Incumbent races: Closer than they appear. The Polling Report, 5, 1-3. Payne, J. W., Bettman, J. R., & Johnson, E. J. (1993). The adaptive decision maker. New York: Cambridge University Press. Risen, J. L., & Gilovich, T. (2007a). Another look at why people are reluctant to exchange lottery tickets. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 1422. Risen, J. L., & Gilovich, T. (2007b). Why people are reluctant to tempt fate. Manuscript in preparation. 26 Ritov, I., & Baron, J. (1992). Status-quo and omission biases. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 4, 49-62. Rozin, R. & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5, 296-321. Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1, 7-59. Simmons, J. P., & Nelson, L. D. (2006). Intuitive confidence: Choosing between intuitive and nonintuitive alternatives. Journal of Experimental Psychology-General, 135, 409-428. Tetlock, P.E. (1992). The impact of accountability on judgment and choice: Toward a social contingency model. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp 331-376). New York: Academic Press. Tetlock, P.E., & Boettger, R. (1994). Accountability amplifies the status quo effect when change creates victims. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 7, 1-23. Tykocinski, O. E., & Ruffle, B. J. (2003). Reasonable reasons for waiting. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 16, 147-157. Willer, R. (2004). The effects of government-issued terror warnings on presidential approval ratings. Current Research in Social Psychology, 10, 1-12. 27 Authors’ Note This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grants 0241638 and 0542486. We thank Elizabeth McQuilken for her help in collecting some of the reported data and Dennis Regan for commenting on an earlier version of the manuscript. Address correspondence to Thomas Gilovich, Department of Psychology, Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; e-mail: tdg1@cornell. 28 Footnotes 1 By the normative option we mean simply the option that most people would choose, following Webster’s definition of normative as “of, relating or conforming to…norms.” Thus, our usage does not imply anything prescriptive or any connotation that the normative option is the superior option. 2 We use the term default here in its loose sense, denoting what is typically done or what one is encouraged to do in the absence of a compelling reason to do otherwise. This is the sense of the term captured by such statements as “The default is to play for a tie at home and a win on the road” or “The default is to borrow money only to purchase appreciating assets.” We discuss the implications of our findings for people’s responses to “stricter” defaults, or those options that will automatically be enacted unless one chooses otherwise, in the general discussion. 3 A chi-square test was not appropriate for this latter comparison because two of the expected cell frequencies were 5 or less. 29 Table 1. Percentage of Participants Electing to Make the €15,000 Offer When It Was Designated as the Status Quo or Not, as a Function of Priming Condition. Presentation of €15,000 Option Priming Condition Status Quo Control Neutral 75% 20% Doubt 40% 30% 30 Figure 1. Performance of the two (hypothetical) stocks in Experiment 1. 120% Performance 100% 80% 60% BOA UT 40% 20% 0% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Weeks 8 9 10 11 12 31 Figure 2. Percentage of Participants Choosing the Normative Option (Experiment 2) 100% Choice for Normative Option 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Self-Chosen Delay n = 19 Forced Delay n = 21 Immediate Choice n = 20 32 Figure 3. Brand Preference by Focal Option and Prime Condition (Experiment 4) 2.5 Neutral Prime Doubt Prime 2 Preference for Sony 1.5 1 0.5 0 -0.5 -1 Samsung Focal Sony Focal No Focal Option Note: A positive preference score indicates a preference for Sony, a negative score a preference for Samsung.