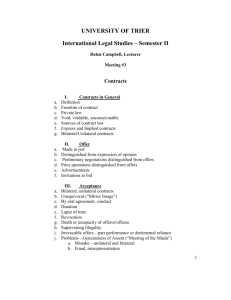

Contracts

advertisement

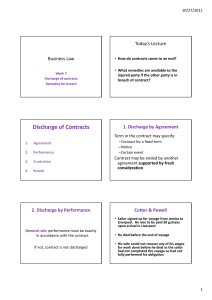

PRIVITY OF CONTRACT As a general rule, only the parties to a contract – the promisor and the promisee – owe any duties and enjoy any rights arising from the contract. Common law recognizes three exceptions: Assignment (of Rights): A transaction whereby an obligee (the assignor) transfers her rights to some third party (the assignee). As a consequence, the assignor’s contract rights are extinguished, and the assignee may demand any performance due to the assignor. Delegation (of Duties): A transaction whereby an obligor (the delegator) frees himself from his duties by having some third party (the delegatee) perform those duties. Despite his delegation, the delegator remains liable for his contract duties if the delegatee fails to perform. Third-Party Beneficiary Contract: A third party, X, is intended, by the terms of the contract between Y and Z, to benefit from Y’s and Z’s performance of the contract. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 1 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) SCOPE OF ASSIGNMENT As a general rule, all contract rights may be assigned, except where: (1) the assignment is prohibited by statute; (2) the contract to be assigned is for personal services, unless all that remains under the contract is a money payment for services previously rendered; (3) the assignment would materially increase the risk or alter the duties of the obligor; or (4) the contract specifically forbids assignment. There are exceptions to this exception, namely the contract may not prevent the assignment of (a) the right to receive money, (b) rights in, or the alienation of, real property, (c) negotiable instruments, or (d) the right to recover damages for breach of contract or for payment of an account under the UCC. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 2 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) SCOPE OF DELEGATION As a general rule, all contract duties may be delegated, except where: (1) the delegator owes the obligee fiduciary duties or other duties arising from a special trust in the delegator; (2) performance depends on the personal skills or talents of the delegator (e.g., Roger Clemens cannot delegate his pitching duties to Annika Sorenstam); (3) performance by the delegatee would vary materially the performance expected by the obligee (e.g., Sue Smith contracts with Annika Sorenstam to give her golf lessons; Annika cannot delegate those duties to her caddie, because Sue wanted Annika’s personal performance); or (4) the contract specifically forbids delegation. If the delegation is enforceable, the obligee must accept performance by the delegatee. But, if the delegatee fails to perform adequately, the delegator remains liable for the delegatee’s breach. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 3 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) INTENDED BENEFICIARIES Intended Beneficiary: A third party for whose benefit a contract is formed. Creditor Beneficiary: A third party who benefits from a contract in which the promisor promises to pay a debt owed by the promisee to the third-party beneficiary. Donee Beneficiary: A third party for whose benefit a contract was made whereby the promisor promised the promisee to make a gift to the third-party beneficiary. An intended third-party beneficiary’s rights vest (i.e., become enforceable), subject to any reservation of rights to the contracting parties, when one of the following occurs: (1) the third party demonstrates manifest assent to the contract (e.g., sends a letter acknowledging awareness of and consent to the contract for her benefit); (2) the third party materially alters her position in detrimental reliance on the contract (e.g., sells her automobile in anticipation of receiving a new automobile pursuant to the contract); or (3) some condition for vesting occurs (e.g., an insured dies vesting the policy beneficiary’s rights). Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 4 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) INCIDENTAL BENEFICIARIES Incidental Beneficiary: A third party who benefits from the performance of a contract, but whose benefit was not the reason the contract was formed. Courts generally ask whether a reasonable person would believe that the promisee intended to confer on the third party (1) the right to bring suit to enforce the contract, and, thereby, (2) the right to benefit from the contract. In so doing, courts consider whether: (1) performance was rendered directly to the third party; (2) the third party has the right to control details of the performance; and (3) the third party is expressly designated in the contract. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 5 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) DISCHARGE AND CONDITION Discharge: The termination of a party’s obligations arising under a contract. Discharge occurs either when: (1) both parties have fully performed their contractual obligations; or (2) events, conduct of the parties, or operation of law release the parties from their obligations to perform. A party’s obligations to perform under a contract may be either absolute or conditioned on the occurrence or nonoccurrence of some event. Condition: A contractual qualification, provision, or clause which creates, suspends, or terminates the obligations of one or both parties to the contract, depending on the occurrence or nonoccurrence of some event. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 6 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) CONTRACTUAL PERFORMANCE Discharge by Performance: A contract terminates when both parties perform or tender performance of the acts they have promised. Tender: An unconditional offer to perform an obligation by a person who is ready, willing, and able to do so. Complete vs. Substantial Performance: When a party fails to completely perform her contractual duties, the question arises whether the performance affords the other party substantially the same benefits as those promised. If so, then the first party is said to have substantially performed. If a party substantially performs, the contract remains in force and the other party must still perform its duties – although it may be entitled to recover damages for the substantially performing party’s failure to perform fully. If a party fails to substantially perform, the other party’s remaining contractual obligations, if any, are discharged. Time for Performance: If no time is stated in the contract, performance is due within a reasonable time. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 7 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) SATISFACTION CONTRACTS Some contracts require one party to perform to the satisfaction of the other. When a contract so provides, courts will apply one of two tests depending on the circumstances: Subjective Satisfaction: When the purpose of the performance is to satisfy personal taste, aesthetics, and the like (e.g., painting a portrait of a customer’s beloved), the court will ask whether the party to be satisfied was, in good faith, satisfied or dissatisfied with the performance. Objective Satisfaction: When the purpose of the performance is to serve some function (e.g., roofing a warehouse to keep out the elements), the court will ask whether a reasonable person would be satisfied or dissatisfied with the performance. Satisfaction of a Third Party: Some contracts require that the performance satisfy some non-party (e.g., an art critic, an architect, an independent lab). Courts tend toward the objective satisfaction standard in these cases, but some have applied the subjective satisfaction test when the third party’s expertise goes to the same factors that would lead a court to apply the subjective test if a party’s satisfaction was at stake. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 8 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) BREACH AND REPUDIATION Material Breach: A party’s failure, without legal excuse, to substantially perform her contractual obligations. If a party’s breach is non-material, the non-breaching party’s duty to perform may be suspended until the breach is remedied, or “cured.” However, a nonmaterial breach will not excuse performance by the nonbreaching party. Only a material breach will excuse the non-breaching party from its contractual obligations. If time is not “of the essence,” failure to perform by the time specified in the contract is not a material breach. Anticipatory Repudiation: An action by a party to a contract that indicates that she will not perform a contractual obligation due to be performed in the future. Such a repudiation will excuse the non-repudiating party from performing under the contract. However, until the non-repudiating party treats the repudiation as a material breach, the repudiating party can retract her repudiation and restore the parties’ contractual rights and obligations. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 9 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) DISCHARGE BY AGREEMENT Rescission: The process by which the parties cancel a contract and return one another to their pre-contract status. Novation: A new contract, which replaces one or more of the parties to the original contract, thereby terminating the original parties’ rights and duties under the original contract. Novation requires (1) a valid, prior agreement, for which (2) all parties agree to substitute a new contract; (3) discharge of the prior obligation; and (4) a valid, new agreement. Accord and Satisfaction: An agreement between the parties to accept different performance than originally promised. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 10 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) DISCHARGE BY OPERATION OF LAW Material Alteration: If the material terms of a contract are altered, an innocent party (i.e., one who neither altered nor consented to the alteration of the contract) may be discharged from their contractual obligations. Statutes of Limitations: A plaintiff suing for breach of contract must file suit within the time permitted by applicable law. Failure to do so does not technically discharge the parties, but it prevents the wronged party from seeking judicial remedies. Example: A plaintiff alleging breach of a contract governed by Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code must file suit within four years of the date of the breach, regardless of the injured party’s knowledge of the breach. Bankruptcy: A discharge in bankruptcy, afforded to a debtor after its liquidation or reorganization plan is approved, bars subsequent enforcement against the debtor of any contracts that pre-date the discharge. Unlike promises to pay or partial payment of a debt barred by limitations, promises to pay or partial payment of a debt following discharge does not revive the debt. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 11 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) IMPOSSIBILITY, IMPRACTICABILITY, AND FRUSTRATION OF PURPOSE A party may be excused when performance becomes either impossible or impracticable through no fault of either party. The following will generally excuse performance as objectively impossible or impracticable: (1) death or incapacitation prior to performance of a personal services contract; (2) destruction of the subject matter of the contract prior to performance; (3) a change in the applicable law that makes performance illegal; (4) changing market conditions make commercially impracticable; and performance (5) frustration of purpose – supervening circumstances making it impossible for both parties to achieve the purpose of the contract. Temporary vs. Permanent: A change in circumstances that makes performance temporarily impossible or impracticable will act to suspend, but not excuse, performance. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 12 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) TYPES OF MONETARY DAMAGES A breach of contract entitles the non-breaching party to sue for money damages, including: Compensatory Damages: Damages that compensate the non-breaching party for the injuries or losses actually sustained as a result of the breach. Incidental Damages: Expenses or costs that are caused by the breach of contract, such as the costs incurred in obtaining performance from another source. Consequential Damages: Damages resulting indirectly from the breach, which were reasonably foreseeable to the breaching party at the time the breach occurred. Punitive Damages: Damages designed to punish a wrongdoer and to deter similar conduct in the future. Such damages are generally not recoverable in breach of contract actions, unless the breaching party’s actions give rise to a separate tort claim. Nominal Damages: Damages awarded to the non-breaching party when only a “technical” injury occurred resulting in no actual damages. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 13 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) COMPENSATORY DAMAGES Although there are special formulae for certain types of contracts, compensatory damages are generally calculated as follows: The value of the performance as promised – The value of the performance actually rendered – The value of any loss avoided, or mitigated, by the non-breaching party + Incidental damages to the non-breaching party _______________________________________________ = Compensatory damages. “Market Value” Damages: In cases involving contracts for the sale of goods or, in most states, land, compensatory damages generally equal the difference between the contract price of the goods or land and the fair market price at the time the goods or title to the land was to be delivered. Construction Contracts: The table at the top of p. 291 illustrates the damages available to a building owner or contractor when the other party breaches at various stages before, during, and after the job. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 14 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) MITIGATION, LIQUIDATED DAMAGES, AND PENALTIES Mitigation of Damages: In most situations, when a breach of contract occurs, the non-breaching party has a duty to take whatever action is reasonable to minimize the damages caused by the breach. For example, in most instances, people who are fired by their employer, regardless of the reason, must try to find a new job. Likewise, a thwarted house buyer must take reasonable steps to locate another house. Liquidated Damages: Contracts often contain provisions requiring the breaching party to pay a sum certain of money if he fails to perform as required. These provisions are enforceable as long as (1) damages from a party’s breach were difficult to estimate at the time the parties formed the contract, and (2) the amount of liquidated damages is a reasonable estimate of the value of the promised performance. Penalty: Courts generally will not enforce a liquidated damages clause that requires the breaching party to pay a sum that bears no reasonable relationship to the value of the promised performance. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 15 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) EQUITABLE REMEDIES In addition to the various types of money damages, there are several equitable (i.e., non-damage) remedies available. Rescission: Canceling a contract and returning the parties to their pre-contract position. Restitution: Returning goods, property, or money (or, in the case of goods or property, their value in money) previously transferred in order to restore the nonbreaching party to his pre-contract position. Specific Performance: Requiring the breaching party to perform exactly as called for in the contract. This remedy is usually granted only when money damages would be an inadequate remedy and the subject matter of the contract is unique (e.g., contract to purchase an original Picasso or a particular tract of land). Reformation: A remedy allowing the contract to be rewritten to reflect the true intent of the parties. This remedy is typically limited to cases of fraud or mutual mistake. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 16 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) PREVENTING UNJUST ENRICHMENT As a general principle, equity requires that when one party confers something of value or other benefit, the other party must pay a reasonable value (in money or other valuable goods or services) for it. Quasi-contractual recovery is particularly useful when one party has partially performed under a contract that subsequently becomes unenforceable. The party seeking to recover must show that: (1) he conferred a benefit on the other party (2) reasonably expecting to be paid or otherwise compensated for the benefit conferred; (3) he did not voluntarily confer benefits for which he did not intend to be paid; and (4) allowing the party receiving the benefit to retain the benefit without paying for it would unjustly enrich the party receiving the benefit. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 17 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.) ELECTION OF REMEDIES In many cases, a non-breaching party has many remedies available. However the one satisfaction rule prohibits an injured plaintiff from recovering more than the full measure of her damages or the full vindication of her rights at common law. As a consequence, a plaintiff who has succeeded at trial on more than one theory of remedy must elect which remedy or remedies she will receive. Article 2 of the Uniform Commercial Code expressly rejects the doctrine in cases regarding a contract for the sale of goods. Article 2 remedies are, thus, cumulative. Ch. 9: Contracts: Third Party Rights, Discharge, Breach, and Remedies - No. 18 Business Law Today: The Essentials (7th ed.)