chapter ten - "other insurance" clauses

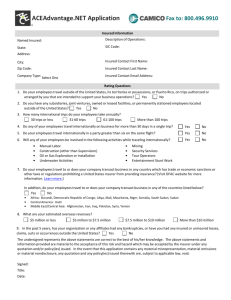

advertisement