Ancient World Primary Docs

advertisement

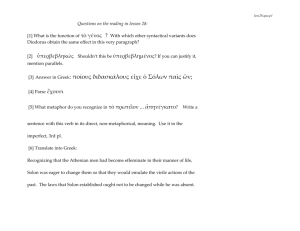

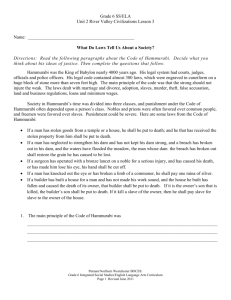

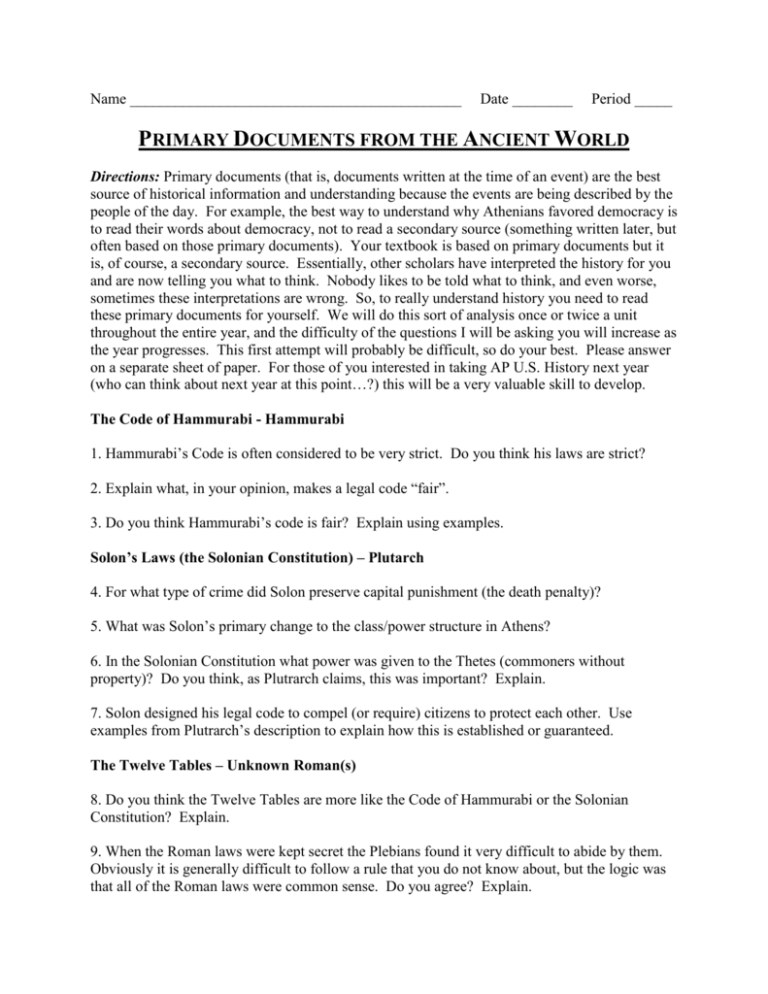

Name ____________________________________________ Date ________ Period _____ PRIMARY DOCUMENTS FROM THE ANCIENT WORLD Directions: Primary documents (that is, documents written at the time of an event) are the best source of historical information and understanding because the events are being described by the people of the day. For example, the best way to understand why Athenians favored democracy is to read their words about democracy, not to read a secondary source (something written later, but often based on those primary documents). Your textbook is based on primary documents but it is, of course, a secondary source. Essentially, other scholars have interpreted the history for you and are now telling you what to think. Nobody likes to be told what to think, and even worse, sometimes these interpretations are wrong. So, to really understand history you need to read these primary documents for yourself. We will do this sort of analysis once or twice a unit throughout the entire year, and the difficulty of the questions I will be asking you will increase as the year progresses. This first attempt will probably be difficult, so do your best. Please answer on a separate sheet of paper. For those of you interested in taking AP U.S. History next year (who can think about next year at this point…?) this will be a very valuable skill to develop. The Code of Hammurabi - Hammurabi 1. Hammurabi’s Code is often considered to be very strict. Do you think his laws are strict? 2. Explain what, in your opinion, makes a legal code “fair”. 3. Do you think Hammurabi’s code is fair? Explain using examples. Solon’s Laws (the Solonian Constitution) – Plutarch 4. For what type of crime did Solon preserve capital punishment (the death penalty)? 5. What was Solon’s primary change to the class/power structure in Athens? 6. In the Solonian Constitution what power was given to the Thetes (commoners without property)? Do you think, as Plutrarch claims, this was important? Explain. 7. Solon designed his legal code to compel (or require) citizens to protect each other. Use examples from Plutrarch’s description to explain how this is established or guaranteed. The Twelve Tables – Unknown Roman(s) 8. Do you think the Twelve Tables are more like the Code of Hammurabi or the Solonian Constitution? Explain. 9. When the Roman laws were kept secret the Plebians found it very difficult to abide by them. Obviously it is generally difficult to follow a rule that you do not know about, but the logic was that all of the Roman laws were common sense. Do you agree? Explain. THE CODE OF HAMMURABI – HAMMURABI Hammurabi was the ruler who chiefly established the greatness of Babylon, the world's first metropolis. Many relics of Hammurabi's reign ([1795-1750 BC]) have been preserved. By far the most remarkable of the Hammurabi records is his code of laws, the earliest-known example of a ruler proclaiming publicly to his people an entire body of laws (282 in total), arranged in orderly groups, so that all men might read and know what was required of them. The code was carved upon a black stone monument, eight feet high, and clearly intended to be installed in public view. Listed below is a selection of the laws. 3. If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death. 5. If a judge try a case, reach a decision, and present his judgment in writing; if later error shall appear in his decision, and it be through his own fault, then he shall pay twelve times the fine set by him in the case, and he shall be publicly removed from the judge's bench, and never again shall he sit there to render judgement. 16. If any one receive into his house a runaway male or female slave of the court, or of a freedman, and does not bring it out at the public proclamation of the major domus, the master of the house shall be put to death. 22. If any one is committing a robbery and is caught, then he shall be put to death. 23. If the robber is not caught, then shall he who was robbed claim under oath the amount of his loss; then shall the community, and . . . on whose ground and territory and in whose domain it was compensate him for the goods stolen. 25. If fire break out in a house, and some one who comes to put it out cast his eye upon the property of the owner of the house, and take the property of the master of the house, he shall be thrown into that self-same fire. 53. If any one be too lazy to keep his dam in proper condition, and does not so keep it; if then the dam break and all the fields be flooded, then shall he in whose dam the break occurred be sold for money, and the money shall replace the corn which he has caused to be ruined. 54. If he be not able to replace the corn, then he and his possessions shall be divided among the farmers whose corn he has flooded. 109. If conspirators meet in the house of a tavern-keeper, and these conspirators are not captured and delivered to the court, the tavern-keeper shall be put to death. 126. If any one who has not lost his goods state that they have been lost, and make false claims: if he claim his goods and amount of injury before God, even though he has not lost them, he shall be fully compensated for all his loss claimed. (i.e., the oath is all that is needed.) 136. If any one leave his house, run away, and then his wife go to another house, if then he return, and wishes to take his wife back: because he fled from his home and ran away, the wife of this runaway shall not return to her husband. 195. If a son strike his father, his hands shall be hewn off. 196. If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out. 197. If he break another man's bone, his bone shall be broken. 200. If a man knock out the teeth of his equal, his teeth shall be knocked out. 202. If any one strike the body of a man higher in rank than he, he shall receive sixty blows with an ox-whip in public. 203. If a free-born man strike the body of another free-born man or equal rank, he shall pay one gold mina. 205. If the slave of a freed man strike the body of a freed man, his ear shall be cut off. 206. If during a quarrel one man strike another and wound him, then he shall swear, "I did not injure him wittingly," and pay the physicians. 209. If a man strike a free-born woman so that she lose her unborn child, he shall pay ten shekels for her loss. 210. If the woman die, his daughter shall be put to death. 215. If a physician make a large incision with an operating knife and cure it, or if he open a tumor (over the eye) with an operating knife, and saves the eye, he shall receive ten shekels in money. 218. If a physician make a large incision with the operating knife, and kill him, or open a tumor with the operating knife, and cut out the eye, his hands shall be cut off. 221. If a physician heal the broken bone or diseased soft part of a man, the patient shall pay the physician five shekels in money. 224. If a veterinary surgeon perform a serious operation on an ass or an ox, and cure it, the owner shall pay the surgeon one-sixth of a shekel as a fee. 225. If he perform a serious operation on an ass or ox, and kill it, he shall pay the owner onefourth of its value. 228. If a builder build a house for some one and complete it, he shall give him a fee of two shekels in money for each sar of surface. 229 If a builder build a house for some one, and does not construct it properly, and the house which he built fall in and kill its owner, then that builder shall be put to death. 230. If it kill the son of the owner the son of that builder shall be put to death. 231. If it kill a slave of the owner, then he shall pay slave for slave to the owner of the house. 232. If it ruin goods, he shall make compensation for all that has been ruined, and inasmuch as he did not construct properly this house which he built and it fell, he shall re-erect the house from his own means. 233. If a builder build a house for some one, even though he has not yet completed it; if then the walls seem toppling, the builder must make the walls solid from his own means. 257. If any one hire a field laborer, he shall pay him eight gur of corn per year. 258. If any one hire an ox-driver, he shall pay him six gur of corn per year. 261. If any one hire a herdsman for cattle or sheep, he shall pay him eight gur of corn per annum. 271. If any one hire oxen, cart and driver, he shall pay one hundred and eighty ka of corn per day. 273. If any one hire a day laborer, he shall pay him from the New Year until the fifth month (April to August, when days are long and the work hard) six gerahs in money per day; from the sixth month to the end of the year he shall give him five gerahs per day. 282. If a slave say to his master: "You are not my master," if they convict him his master shall cut off his ear. SOLON’S LAWS (THE SOLONIAN CONSTITUTION) – PLUTARCH OVRVIEW The Athenian leader Solon devised a new law code in 597 B.C. Fearing his own rise to power as a tyrant like Draco (a previous leader) Solon entered exile for ten years following the introduction of his constitution. His reforms are remarkable in many respects, but particularly because they laid the foundation for a democratic form of government in Athens; in the following excerpt, the Greek biographer Plutarch discusses Solon's reforms. First, then, [Solon] repealed the laws of Draco, except those concerning murder, because of the severity of the punishments they appointed, which for almost all offences were capital; even those that were convicted of idleness were to suffer death, and such as stole only a few apples or [plants] were to be punished in the same manner as sacrilegious persons and murderers. Hence a saying of Demades, who lived long after, was much admired, that Draco wrote his laws not with ink but with blood. And he himself being asked, “Why he made death the punishment for most offences, answered”, answered “Small ones deserve it, and I can find no greater for the most heinous”. When Solon undertook the annulling of debts, and was considering of a suitable speech and a proper method of introducing the plan, he told some of his most intimate friends, namely, Conon, Clinias, and Hipponicus, that he intended only to abolish the debts, and not to meddle with the lands. These friends of his hastening to make their advantage of the secret, before the decree took place, borrowed large sums of the rich, and purchased estates with them. Afterward, when the decree was published, they kept their possessions without paying the money they had taken up; which brought great reflections upon Solon, as if he had not been imposed upon with the rest, but were rather an accomplice in the fraud. This charge, however, was soon removed, by his being the first to comply with the law, and remitting a debt. But his friends went by the name of Chreocopiæ, or debt-cutters, ever after. The method he took satisfied neither the poor nor the rich. The rich were displeased by the cancelling of their bonds; and the poor at not finding a division of lands; upon this they had fixed their hopes, and they complained that he had not made all the citizens equal in estate. But being soon sensible of the utility of the decree, they laid aside their complaints, and constituted Solon lawgiver and superintendent of the commonwealth; committing to him the regulation not of a part only, but the whole, magistracies, assemblies, courts of judicature, and senate; and leaving him to determine the qualification, number, and time of meeting for them all, as well as to abrogate or continue the former constitutions, at his pleasure. First, then, he repealed the laws of Draco, except those concerning murder In the next place, Solon took an estimate of the estates of the citizens; intending to leave the great offices in the hands of the rich, but to give the rest of the people a share in other departments which they had not before. He created three upper classes based on various levels of wealth and abolished rights based solely on birth, a significant change from the past. All people who did not meet the wealth requirements for those classes were named Thetes, and not admitted to any office: they had only a right to appear and give their vote in the general assembly of the people. This seemed at first but a slight privilege, but afterward showed itself a matter of great importance: for most causes came at last to be decided by them; and in such matters as were under the cognizance of the magistrates there lay an appeal to the people. Desirous yet further to strengthen the common people, he empowered any man whatever to enter an action for one that was injured. If a person was assaulted, or suffered damage or violence, another that was able and willing to do it might prosecute the offender. Thus the lawgiver wisely accustomed the citizens, as members of one body, to feel and to resent (or dislike) one another’s injuries. As he often explained, “[now] those who are not injured in a crime are as ready to prosecute and punish offenders as those who are injured”. As Attica (the region surrounding and including Athens) was not supplied with water from perennial rivers, lakes, or springs, but chiefly by wells dug for that purpose, he made a law, that where there was a public well, all within the distance of four furlongs, should make use of it; but where the distance was greater, they were to provide a well of their own. And if they dug ten fathoms deep in their own ground, and could find no water, they had liberty to fill a vessel of six gallons twice a day at their neighbor's. Thus he thought it proper to assist persons in real necessity, but not to encourage idleness. All his laws were to continue in force for a hundred years, and were written upon wooden tables. The Senate, in a body, bound themselves by oath to establish the laws of Solon; and the Thesmothetæ, or guardians of the laws, took an oath in a particular form, by the stone in the market-place, that for every law they broke, each would dedicate a golden statue at Delphi of the same weight with himself. THE TWELVE TABLES – UNKNOWN ROMAN(S) OVRVIEW According to tradition during the earliest period of the Republic the laws were kept secret by the from the plebeians (commoners) and were enforced with untoward severity, especially against the plebeians. A plebeian named Terentilius proposed in 462 BC that an official legal code should be published, so the plebeians could not be surprised and would know the law, but there was great resistance from the upper classes. Nevertheless, less than 15 years later, in 449 BC the Twelve Tables were produced and all Roman laws were publically displayed. Like most other early codes of law, they combine strict and rigorous penalties with equally strict and rigorous procedures for enforcing the laws and determining guilt. The historical record of the Twelve Tables remains incomplete, but historians have pieced together many aspects. Table I 1. If anyone summons a man before the magistrate, he must go. If the man summoned does not go, let the one summoning him call the bystanders to witness and then take him by force. 2. If he shirks or runs away, let the summoner lay hands on him. 3. If illness or old age is the hindrance, let the summoner provide a team. 4. Let the protector of a landholder be a landholder; for one of the proletariat (in Roman law those with little or no property), let anyone that cares, be protector. Table II 2. He whose witness has failed to appear may summon him by loud calls before his house every third day. Table III 1. One who has confessed a debt, or against whom judgment has been pronounced, shall have thirty days to pay it in. After that forcible seizure of his person is allowed. The creditor shall bring him before the magistrate. Unless he pays the amount of the judgment or some one in the presence of the magistrate interferes in his behalf as protector the creditor so shall take him home and fasten him in stocks or fetters. He shall fasten him with not less than fifteen pounds of weight or, if he choose, with more. If the prisoner choose, he may furnish his own food. If he does not, the creditor must give him a pound of meal daily; if he choose he may give him more. 2. On the third market day let them divide his body among them. If they cut more or less than each one's share it shall be no crime. 3. Against a foreigner the right in property shall be valid forever. Table IV 1. A dreadfully deformed child shall be quickly killed. 2. If a father sell his son three times, the son shall be free from his father. 3. As a man has provided in his will in regard to his money and the care of his property, so let it be binding. Table V 1. Females should remain in guardianship even when they have attained their majority. Table VII 1. Let them keep the road in order. If they have not paved it, a man may drive his team where he likes. 9. Should a tree on a neighbor's farm be bend crooked by the wind and lean over your farm, you may take legal action for removal of that tree. 10. A man might gather up hsi fruit that was falling down onto another man's farm. Table VIII 2. If one has maimed a limb and does not compromise with the injured person, let there be retaliation. If one has broken a bone of a freeman with his hand or with a cudgel, let him pay a penalty of three hundred coins If he has broken the bone of a slave, let him have one hundred and fifty coins. If one is guilty of insult, the penalty shall be twenty-five coins. 3. If one is slain while committing theft by night, he is rightly slain. 4. If a patron shall have devised any deceit against his client, let him be accursed. 5. If one shall permit himself to be summoned as a witness, if he does not give his testimony, let him be noted as dishonest and incapable of acting again as witness. 10. Any person who destroys by burning any building or heap of corn deposited alongside a house shall be bound, scourged, and put to death by burning at the stake provided that he has committed the said misdeed with malice aforethought; but if he shall have committed it by accident, that is, by negligence, it is ordained that he repair the damage or, if he be too poor to be competent for such punishment, he shall receive a lighter punishment. 13. It is unlawful for a thief to be killed by day....unless he defends himself with a weapon; even though he has come with a weapon, unless he shall use the weapon and fight back, you shall not kill him. And even if he resists, first call out so that someone may hear and come up. 23. A person who had been found guilty of giving false witness shall be hurled down from the Tarpeian Rock (a steep cliff overlooking the Roman Forum). 26. No person shall hold meetings by night in the city. Table IX 4. The penalty shall be capital for a judge or arbiter legally appointed who has been found guilty of receiving a bribe for giving a decision. 5. Treason: he who shall have roused up a public enemy or handed over a citizen to a public enemy must suffer capital punishment. 6. Putting to death of any man, whosoever he might be unconvicted is forbidden. Table X 1. None is to bury or burn a corpse in the city. 3. The women shall not tear their faces nor wail on account of the funeral. Table XI 1. Marriages should not take place between plebeians (the lower class) and patricians (the upper class). Table XII 5. Whatever the people had last intended should be held as binding by law.