1 - Medics Without A Paddle

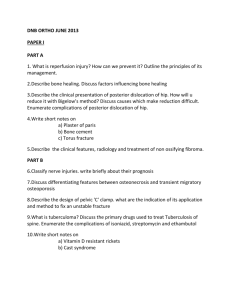

advertisement