General Instruction of the Roman Missal Article

advertisement

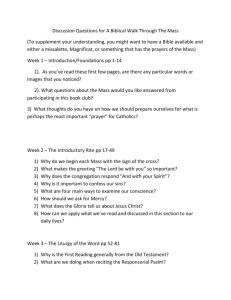

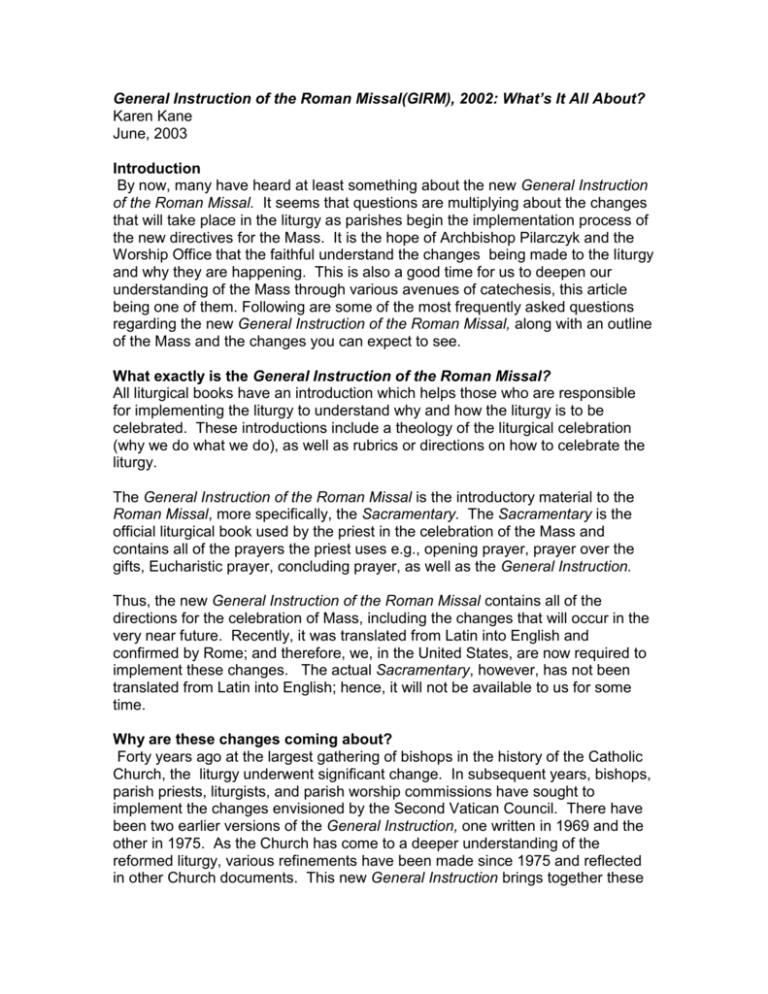

General Instruction of the Roman Missal(GIRM), 2002: What’s It All About? Karen Kane June, 2003 Introduction By now, many have heard at least something about the new General Instruction of the Roman Missal. It seems that questions are multiplying about the changes that will take place in the liturgy as parishes begin the implementation process of the new directives for the Mass. It is the hope of Archbishop Pilarczyk and the Worship Office that the faithful understand the changes being made to the liturgy and why they are happening. This is also a good time for us to deepen our understanding of the Mass through various avenues of catechesis, this article being one of them. Following are some of the most frequently asked questions regarding the new General Instruction of the Roman Missal, along with an outline of the Mass and the changes you can expect to see. What exactly is the General Instruction of the Roman Missal? All liturgical books have an introduction which helps those who are responsible for implementing the liturgy to understand why and how the liturgy is to be celebrated. These introductions include a theology of the liturgical celebration (why we do what we do), as well as rubrics or directions on how to celebrate the liturgy. The General Instruction of the Roman Missal is the introductory material to the Roman Missal, more specifically, the Sacramentary. The Sacramentary is the official liturgical book used by the priest in the celebration of the Mass and contains all of the prayers the priest uses e.g., opening prayer, prayer over the gifts, Eucharistic prayer, concluding prayer, as well as the General Instruction. Thus, the new General Instruction of the Roman Missal contains all of the directions for the celebration of Mass, including the changes that will occur in the very near future. Recently, it was translated from Latin into English and confirmed by Rome; and therefore, we, in the United States, are now required to implement these changes. The actual Sacramentary, however, has not been translated from Latin into English; hence, it will not be available to us for some time. Why are these changes coming about? Forty years ago at the largest gathering of bishops in the history of the Catholic Church, the liturgy underwent significant change. In subsequent years, bishops, parish priests, liturgists, and parish worship commissions have sought to implement the changes envisioned by the Second Vatican Council. There have been two earlier versions of the General Instruction, one written in 1969 and the other in 1975. As the Church has come to a deeper understanding of the reformed liturgy, various refinements have been made since 1975 and reflected in other Church documents. This new General Instruction brings together these changes into a single document. However, the underlying theology of full, conscious and active participation by the faithful continues to remain a priority in the way we as Catholics worship. Other reasons for the changes found in the new General Instruction include: to increase a sense of reverence among the faithful in the way we celebrate the liturgy; to create a more unified celebration of the liturgy; and finally, to make a clearer distinction of roles between the ordained minister and the non-ordained. The overall goal, however, is that we celebrate the liturgy well, with hearts and voices offering praise and thanksgiving to God. What kinds of changes should be expected in the Mass? Most of the changes in the new General Instruction are not significant, and they are certainly not as broad as those that took place right after the Second Vatican Council. Many of the changes that you might notice in the liturgy are really refinements in the way we celebrate the Mass. Some of the changes that you will see are not new directives in the General Instruction, but were never implemented in the first place. Hence, parish worship commissions are using the implementation of the new General Instruction as an opportunity to refine the celebration of the liturgy overall so that it more closely reflects the universal law of the Church. Later in this article the various changes in the Mass will be described in detail. When do the changes need to take place? Archbishop Pilarczyk has set the Feast of the Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ, June 22, 2003, as the official date of implementation of the new General Instruction for the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Several workshops were held throughout the Archdiocese for priests, deacons, parish pastoral staffs, and worship commissions to inform them of the various changes that are to take place. These workshops marked the beginning of a process of liturgical catechesis which, hopefully, has continued over the past few months in parishes so that all our Catholics will understand why the changes have come about and what they mean. Bulletin inserts have been provided to parishes through the Worship Office of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati, and many parishes have taken advantage of these inserts to help the faithful. Will these changes make Mass the same everywhere? While there will be a certain amount of uniformity in the way that we worship, there will always be diversity in our celebration of the Mass, because the communities that gather week after week have their own cultural and local customs that will be reflected in their worship. Diversity in practice is not a bad thing, and the General Instruction allows for such diversity. The document encourages the local ordinary to make many decisions regarding the way the liturgy is to be celebrated in his diocese. Therefore, how we celebrate the liturgy in Cincinnati could be different from other dioceses around the country. Moreover, there are places in the document which uses language that is less directive, allowing for possible interpretation of the law. However, having said this, the new General Instruction does give us the opportunity to look at the way we worship and refine our practices so that in areas where it is important to be uniform in practice we can make such adjustments. No matter what, the liturgy should be celebrated reverently, prayerfully, and with an understanding of what it is that we are doing. The following articles are a walk-thru of the Mass with some explanation about what it is that we are celebrating, including the changes one can expect to see in the near future. Top of Page Introductory Rites Emily J. Besl June 2003 Introductory Rites How does the new General Instruction affect the celebration of the Introductory Rites at Mass? In this section of the Mass -- which extends from the opening hymn until all sit for the readings -- there are a few changes, but not much that would be noticeable to the whole assembly. For instance, while the parts of the Introductory Rites remain the same, the names of some parts have changed. The entrance song is now called the “entrance chant.” The penitential rite is referred to as the “act of penitence,” and the opening prayer has returned to its Latin name of “collect.” The Book of the Gospels One thing that will appear different in practice for many parishes is the custom of carrying the book of the gospels rather than the lectionary in the entrance procession. In fact, the previous General Instruction also called for the gospel book at this point and did not mention the lectionary. However, when the General Instruction first appeared in 1969, the book of the gospels had not yet been published in English. So parishes used what they had instead: the lectionary. The current General Instruction now specifically asks that the lectionary not be carried in procession. The deacon, as the one who proclaims the gospel, carries the gospel book if he is present. But in the absence of a deacon, a lay minister may carry the gospel book and place it on the altar. If the gospel book is not carried in the entrance procession, it is to be placed on the altar before Mass begins. Reverence to the Altar The new General Instruction gives more detailed directions about the proper reverence shown to the altar or to the tabernacle as the entrance procession approaches the altar. The priest and other ministers reverence the altar, a sign of the presence of Christ who offers himself there, with a profound bow -- a bow from the waist. Those carrying items such as the cross or candles do not bow. If there is a tabernacle with the Blessed Sacrament behind the altar in the sanctuary, then the priest and ministers genuflect at the entrance and at the end of Mass, but not during the Mass itself. Again, those carrying cross and candles do not genuflect, but instead bow their heads. Silence An aspect of Mass that is stressed throughout the new General Instruction is the importance of silence. In the Introductory Rites, silence occurs at the act of penitence and after the invitation to pray at the collect. Here, the purpose of silence is for recollection; these are moments to compose ourselves, to recognize that we are in God’s presence, to call to mind our sins or our intentions for prayer. In addition, the new General Instruction encourages communities to observe a period of silence before Mass begins, so that everyone may be prepared to celebrate the sacred liturgy together with their whole heart. This does not rule out having prelude music at some point just before Mass, since the prelude can also foster a sense of recollection and preparation. Gathered as God’s Holy People “The purpose of these rites is that the faithful who are assembling should become a community…” (GIRM ’02, n. 46). Before we can hear the word of God and celebrate the Eucharist together, we carry out the Introductory Rites to help us realize that we pray the Mass not as individuals but as the Body of Christ. These rites make the transition between our everyday lives and the sacred action we are about to perform together as the holy people of God. That’s why the “collect” is the climax and completion of the Introductory Rites. All of our personal prayers are gathered and “collected” into one prayer offered to God by the priest in our name. These words from the General Instruction state so beautifully what the Introductory Rites are meant to make us all aware of. “The celebration of the Eucharist is the action of the whole Church…. For these people are the people of God, purchased by Christ’s Blood, gathered together by the Lord, nourished by his word. They are a people called to offer God the prayers of the entire human family, a people giving thanks in Christ for the mystery of salvation by offering his sacrifice. Finally they are a people growing together into unity by sharing in the Communion of Christ’s body and Blood. These people are holy by their origin, but becoming ever more holy by conscious, active, and fruitful participation in the mystery of the Eucharist” (GIRM ’02, n. 5). Top of Page Liturgy of the Word Emily J. Besl June 2003 As with the Introductory Rites, the new General Instruction introduces no major changes in the Liturgy of the Word. Several new paragraphs have been inserted in the 2002 General Instruction that did not appear in the 1975 version, but much of this new material comes from liturgical documents that have come into force since 1975, such as the 1997 Lectionary for Mass. Some of the new material does not contain directives for how to celebrate the Word, but rather has short explanations with insights about the meaning or purpose of a certain part of the Mass, especially parts belonging to the congregation. When we say, “Thanks be to God,” at the end of a reading, “the gathered people honor the word of God that they have received in faith and with grateful hearts.” Reflecting on statements like this can help us appreciate what we are to do in the Liturgy of the Word. Do we realize that in this brief response we are honoring God’s word? Have we, in fact, received the word in faith? For what in this reading are we grateful? Similarly, the new General Instruction clarifies the role of the psalm in the Liturgy of the Word, saying it is important because it encourages meditation on the word. For this and other reasons, the psalm is to be sung, at least the people’s response. Do we allow the psalm to lead us in meditation on God’s word? Do we sing it in such a way as to promote meditation? The purpose of the Alleluia is also given: “By it the assembly of the faithful welcomes and greets Lord who is about to speak to them in the Gospel, and professes its faith by singing.” Have we thought of this acclamation as a way to welcome Christ, present in his word? Do we realize its importance as a profession of faith that we all sing together every time we prepare to hear Christ speaking in the gospel? A few new directives do appear concerning the Liturgy of the Word. Everyone is to turn toward the ambo in anticipation of listening to Christ in the gospel, and all are to make the sign of the cross on the forehead, mouth, and heart. While many people already do this gesture, it had not been previously been mentioned for the congregation. No words are given to accompany this gesture, but it indicates a prayer that Christ’s word that we are about to hear may always be in our minds, in our words, and in our hearts. The options for the place where the homily is delivered have been expanded. In addition to the chair or the ambo, the homily may also be given from “another suitable place.” If more than one reader is available, the new General Instruction, as does the Lectionary for Mass, prefers that each reading have its own reader. This practice enables the reader to prepare one passage well, so that they can meaningfully proclaim God’s word to the assembly, and not simply read the text aloud. However, a single reading is not to be divided among several persons, except for the Passion on Palm Sunday and Good Friday. One directive that appeared in the previous edition of the General Instruction but has not often been put into practice is the profound bow in the Nicene Creed. All are to bow from the waist at the words, “by the power of the Holy Spirit…and became man.” On the Annunciation and Christmas, the bow is replaced by a genuflection. Perhaps some are uncomfortable with physical gestures like this, but liturgy is meant to be a prayer of our whole being, not just our minds. A profound bow done by all together can be a powerful bodily expression of our common faith, as well as a strong way to form our faith. Throughout the whole Liturgy of the Word, a slow and unhurried pace is called for, as well as periods of silence. This is expressed in forceful language; it is not only encouraged but demanded. “The liturgy of the word must be celebrated in such a way as to promote meditation. For this reason, any sort of haste that hinders recollection must be clearly avoided” (GIRM ‘02, n. 56). “Sacred silence, as part of the celebration, must be observed at the designated times” (n. 45). After the readings and the homily, the purpose of silence is to allow the Holy Spirit to help “the word of God be grasped by the heart” (n. 56). We spend some moments reflecting on what we have heard in the Scriptures. What images or phrases stay in our minds? What is God saying to me at this time? To the parish? To our nation or our world? What is our response to God’s word? Top of Page Liturgy of the Eucharist Karen Kane June, 2003 At the Last Supper Christ instituted the paschal sacrifice and meal. . .For Christ took the bread and the cup and gave thanks; he broke the bread and gave it to his disciples, saying: A take, eat, and drink: this is my Body; this is the cup of my Blood. Do this in memory of me.@ Accordingly, the Church has arranged the entire celebration of the liturgy of the Eucharist in parts corresponding to these words and actions of Christ. (GIRM >02, n.72) The liturgy of the Eucharist is the part of the Mass that begins with the preparation of the gifts and ends with Holy Communion [and the prayer after Communion]. It is the time in which we offer gifts of bread and wine to be prayed over, broken and shared. We pray the great prayer of thanksgiving for the many deeds God has done in and through Jesus Christ. And finally, we eat and drink of the Body and Blood of Christ that we might be nourished to go out to the world to be Christ to those who are most in need of our love and care. These actions of Christ, taking, blessing, breaking and sharing, constitute the liturgy of the Eucharist: the preparation of the gifts, the Eucharistic Prayer, and the breaking of bread and Communion. Preparation of the Gifts: The preparation of the gifts is considered to be a transitional part of the Mass in that it moves us from the celebration of the Liturgy of the Word into the celebration of the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The Word proclaimed and preached has brought us to a place in which we are ready to offer thanks and praise. The preparation of the gifts begins with the collection and procession of gifts to the altar, with the gifts being received by the priest or deacon at the altar. The General Instruction tells us that it is APraiseworthy for the faithful to present the bread and wine. . .Even though the faithful no longer, as in the past, bring from their own possessions the bread and wine intended for the liturgy, nevertheless the rite of carrying up the offerings still retains its power and spiritual significance. (GIRM >02, n.73). The carrying forward of the gifts symbolizes the giving of ourselves to be offered to God and to be made holy for the life of the world. Once the gifts of bread and wine have been placed on the altar with the accompanying prayers said by the priest privately, the priest then invites the people to pray. It is at this moment in the liturgy that a noticeable change has been made. After the priest says to the assembly, APray, my brothers and sisters, that our sacrifice may be acceptable to God, the almighty Father,@ the entire assembly will stand rather than remain sitting for their response: AMay the Lord accept this sacrifice. . .@ There is no explanation for this change in the liturgy, and it is not altogether clear why it has been made. Perhaps, one could infer that when we pray we usually stand. After the prayer over the gifts, the Eucharistic Prayer begins. Eucharistic Prayer: The General Instruction describes the Eucharistic Prayer in this way: Now the center and summit of the entire celebration begins, the Eucharistic Prayer, a prayer of thanksgiving and sanctification. The priest invites the people to lift up their hearts to the Lord in prayer and thanksgiving; he unites them with himself in the prayer which, in the name of the entire community, he addresses to God the Father through Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit. . .the meaning of the prayer is that the entire congregation of the faithful should join itself with Christ in confessing the great things God has done and in offering the sacrifice. The Eucharistic Prayer demands that all listen to it with reverence and in silence.@ (GIRM >02, n.78) It is this prayer in which the priest and the community join with Christ to offer praise and thanks to God in response to the Word just proclaimed. While the priest is the one who always prays the prayer out loud, the gathered assembly joins him in prayer through active listening and responding by singing the acclamations. This prayer is the prayer of the community and not just the priest. We all offer our thanks to God for the wonderful things God has done in our lives by our attentiveness to the words of the prayer. Perhaps the area that has concerned many Catholics the most is the posture for the Eucharistic Prayer. There have been a number of articles in the Telegraph (and other places) on kneeling as opposed to standing during the Eucharistic Prayer. In other parts of the world, standing is the universal posture for the Eucharistic Prayer. In these places, standing is not a posture of irreverence, but one of reverence. Those who stand in the great cathedrals of Europe are not being disrespectful of the presence of Christ in bread and wine, but in fact, standing is considered to be a posture of respect. However, in the United States, kneeling is the norm and has been determined by the U.S. Catholic Conference of Bishops to be the posture of the assembly during the Eucharistic Prayer. Nevertheless, the General Instruction does allow for exceptions to this norm, and Archbishop Pilarczyk has outlined some of those exceptions. For example, if a church has no kneelers, the faithful may stand; if the assembly usually gathers around the altar for the Eucharistic Prayer, they may stand; if the faithful are prevented from kneeling for good reason (such as at a priest=s funeral when a number of priests are in attendance and they would block the view of the assembly) the faithful may stand. However, for the most part, kneeling is the normal posture for the Eucharistic Prayer. These things being said, it is important to remember that unity of posture during this time of the Mass is an overriding goal, and whether the posture is kneeling or standing, everyone in the church should be doing the same thing. When the assembly stands during the Eucharistic Prayer, they should make a profound bow while the priest is genuflecting during the institution narrative (consecration). The Eucharistic Prayer is concluded with the doxology and the singing of the Great Amen. Once the assembly has given their assent by singing the Great Amen, they stand to begin the Communion Rite. Top of Page The Communion Rite Rev. Steven P. Walter June 2003 Communion Rite Although there are no changes in the Communion Rite in the General Instruction that one might consider major, there are a few modifications and clarifications that will be noticeable to us when we gather for Mass in the coming weeks and months. These elements in the Communion Rite are further clarified in a companion document, Norms for the Distribution and Reception of Holy Communion Under Both Kinds in the Dioceses of the United States of America, issued in June, 2001. The purpose of both of these documents is to help us to be drawn more deeply into the mystery that we celebrate in the Eucharist. We do this by signs and symbols, words, gestures and song that invite us to enter into the truth of our celebration: the Body of Christ fed and nourished by the Body of Christ to go forth to be the Body of Christ in the world. We are referring here to the part of the Mass that begins with the Our Father, and includes the Rite of Peace, The Breaking of the Bread, and Communion. Within this framework a variety of words, gestures and songs work together to help us encounter Christ. “Christ’s presence in the Eucharist challenges human understanding, logic, and ultimately reason. His presence cannot be known by the senses, but only through faith – a faith that is continually deepened through that communion which takes place between the Lord and his faithful in the very act of the celebration of the Eucharist. (Norms # 12) The Our Father begins this rite with its petitions for “our daily bread” and the forgiveness of our sins. The Church has always understood this as a most appropriate way to begin our immediate preparation for Holy Communion. This is followed by the Rite of Peace, which includes a prayer for peace, as well as the actual sign of peace exchanged by the whole assembly. Here we recognize the presence and peace of Christ in our brothers and sisters gathered in Christ’s name. This is not a hierarchical gesture, that is, it is not passed from the sanctuary down through the church. Rather, at the invitation, all offer the sign of peace to those nearby, a ritual gesture that while given to a few signifies a reality that extends to the whole gathered community. “The gesture of breaking the bread of Christ at the Last Supper gave the entire eucharistic action its name in apostolic times. It is the sign that the many faithful are made one body (I Cor. 10:17) by receiving Communion from the one bread of life which is Christ, who died and rose for the salvation of the world.” (GIRM ’02, #83) The gesture of breaking the consecrated bread and pouring out the Precious Blood invites us to encounter in ritual form the Christ who was broken and poured out for us, and to recognize that pattern both in our own life and the lives of those around us. Here the Norms give a new directive that only the “ordinary” ministers of Communion, that is bishops, priests and deacons, are to perform the action of breaking and pouring. The predecessor to the Norms, a document issued a few years ago, This Holy and Living Sacrifice specifically encouraged involving a few of the extraordinary ministers of Communion to help with this rite as needed. Why the change? Perhaps restricting this action will allow it to stand out more clearly in its ritual and symbolic value. Perhaps we had become a little too “utilitarian” in performing this ritual action too quickly. It may take more time in some parishes now, but the reverent and careful attention to this gesture will give us the opportunity to reflect on the mystery of Christ’s passion, death and resurrection as we prepare to process forward to receive the Body and Blood of Christ. This gesture is accompanied by the singing of the Lamb of God, which should be extended as needed to cover the entire action of breaking and pouring. Both the General Instruction and Norms remind us that Communion is to be administered from the Body and Blood of Christ consecrated at the Mass that is being celebrated. The reception of Communion is a way that we say, “yes” to a life lived in imitation of the Christ we encounter in the entire Eucharistic celebration. Similarly, both documents encourage the reception of Communion under both kinds. “It is most desirable that the faithful, just as the priest himself is bound to do, receive the Lord’s Body from hosts consecrated at the same Mass and that… they participate in the chalice, so that even by means of the signs Communion will stand out more clearly as a participation in the sacrifice actually being celebrated. ( GIRM ’02, # 85) The Communion Procession is a ritual gesture that is symbolic of the pilgrimage of life. Our final goal is eternal life, a life that is promised by Jesus to those who eat his flesh and drink his blood. This procession is not merely utilitarian. It is yet another way that we are drawn into the mystery of this sacrament we celebrate. The singing of the Communion hymn is another ritual element that unites us in voice and prayer as we celebrate our communion with and in Christ. In the dioceses of the United States the proper posture for the reception of Holy Communion is standing. As we move forward in procession to receive the Body and Blood of the Lord, the rite prescribes that a gesture of reverence be made. This “gesture” is not a new requirement. Previous editions of the General Instruction have called for it. However, what is new is that the gesture is now specified. It is a “simple bow.” The bishops felt that it was best that a specified gesture be given. The purpose for specifying this gesture is to ensure unity in the act of communion. Individuals are not free to choose a gesture they prefer or judge to be better. Take your time. The gesture is meant to help us slow down and make this a reverent moment. The basic sequence is this: approach the minister of Holy Communion; bow as the host or chalice is shown to you; respond, “amen” when the minister of Holy Communion says “The Body of Christ.” or “The Blood of Christ.”; communion is then received as the communicant desires, either in the hand or on the tongue. Be careful to bow to the sacred elements, and not to the back of the person in line in front of you. The purpose here is that we take our time and carefully and reverently receive Holy Communion. In some parishes people will kneel after they return to their place from receiving communion. In some parishes all will remain standing until the whole community has received. Either choice is acceptable, but the whole assembly should do the same thing. A period of silence is to follow the communion of the faithful. This is our most common experience. Another option is that all, standing, may sing a congregational hymn of praise. There is no mention or encouragement of a socalled “meditation hymn” at this time in the Mass. The Prayer After Communion brings the Communion Rite to a conclusion. In this prayer the priest prays in the name of all that our reception of Holy Communion may have an effect on our lives. The presider prays this prayer either at the Chair or at the Altar. When prayed at the Altar, the priest would then move to the chair for the Concluding Rite. The Prayer After Communion completed, there follows the simple and straightforward Concluding Rite. This rite begins with a place where any necessary announcements might be made if necessary. The rite then moves to a blessing, either simple or solemn, followed by the dismissal of the assembly by the deacon, or in his absence the priest. There are no changes or modifications during this Concluding Rite. Top of Page