Electronic supplemental methods - Proceedings of the Royal Society B

advertisement

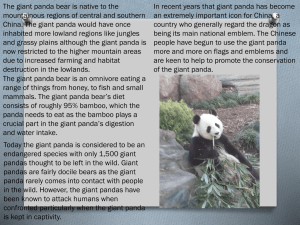

Definition of female fertile phase based on endocrine data Regular urine samples were collected on most days and several times a day as females approached peak oestrus. Urine samples were aspirated from enclosure floors and then indexed by creatinine to adjust for variability in the urine dilution, before being frozen at -20 degrees C until analysis at the endocrinology laboratory of the Wolong research base. When multiple samples were taken the average oestrogen values for each day were used for the analysis. Assays of estrone-3-glucuronide were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (EIA) as previously described (Czekala et al. 2003; McGeehan et al. 2002). This method uses a solid phase assay with antibody-coated microtiter plate wells (antisera made against estrone-3-glucuronide: 100 ul, 1:5000 UCDavis, Davis, CA) used in competition with estrone 3-glucuronide HRP (UCDavis, Davis, CA). The colimetric assay was finalised with the addition of the substrate tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma, St Louis, MO). To account for an excretion lag time of approximately 12-24 hours oestrogen levels were backdated one day. This method has been used in previous studies on giant pandas (Czekala et al. 2003; McGeehan et al. 2002; Lindburg et al. 2001). Moreover, although the lag time for the excretion of urinary oestrogen metabolites in this species has not been established, peak faecal glucocorticoid concentrations are detected approximately 12 hours after peak serum levels (Kersey 2009) and other mammals typically excreted urine steroids on the same day as the peak in serum (Wasser et al. 1994), justifying the use of the urinary peak in this analysis as denoting a significant change in ovarian activity. In giant pandas, a greater than six-fold increase in urinary oestrogen above basal, followed by a rapid decline to baseline concentrations is indicative of ovulation (Steinman et al. 2006) (female oestrogen profiles are provided as electronic supplemental material). Using these criteria we could determine the date of ovulation (designated Day 0 of the reproductive cycle) and group recordings relative to this. In humans, conception probably peaks just before ovulation and the median ovum survival time is approximately 12 hours (Lynch et al. 2006). However, sperm can be fertile for up to 72 hours (Wilcox et al. 1995) and hence, any copulations occurring up to three days before ovulation can still be fertile. Based on this, we defined the ‘fertile’ phase of the female oestrous cycle as the three days prior to ovulation and the date of ovulation itself (-3 to 0 days) and the ‘pre-fertile’ phase as the six days (-4 to -9) immediately preceding this; giving us 219 ‘pre-fertile’ and 460 ‘fertile’ chirps for the comparisons. References Czekala, N. M., McGeehan, L., Steinman, K. J., Xuebing, L. & Gual-Sil, F. 2003 Endocrine monitoring and its application to the management of the giant panda. Zoo Biol. 22, 389-400. Lindburg, D. G., Czekala, N. M. & Swaisgood, R. R. 2001 Hormonal and behavioral relationships during estrus in the giant panda. Zoo Biol. 20, 537-543. Lynch, C. D., Jackson, L. W. & Buck Louis, G. M. 2006 Estimation of the dayspecific probabilities of conception: current state of the knowledge and the relevance for epidemiological research. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. McGeehan, L., Li, X., Jackintell, L., Czekala, N. M., Huang, S. & Wang, A. 2002a Evaluating reproductive performance in giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) with behaviour and hormones. Zoo Biol. 21, 449-466. Steinman, K. J., Monfort, S. L., McGeehan, L., Kersey, D. C., Gual-Sil, F., Snyder, R. J., Wang, P., Nakao, T. & Czekala, N. M. 2006 Endocrinology of the giant panda and application of hormone technology to species management. In Giant pandas: veterinary medicine and management (ed. D. E. Wildt, Zhang, A., Zhang, H., Janssen, D. J., Ellis, S.), pp. 198-230. New York: Cambridge University Press. Wasser, S. K., Monfort, S. L., Southers, J. & Wildt, D. E. 1994 Excretion rates and metabolites of estrodiol and progesterone in baboon (Papio cynocephalus cynocephalus) faeces. J. Reprod. Fertil. 101, 213-220. Table 1: Rotated component matrix to show how our five response measures loaded onto each of the two principal components. The two principal components explained 86% of the variance; eigenvalues are given in upper part of the table and the correlations between the response variables and each principal component in the lower part. Component 1 Component (Looking (Movement response) response) Eigenvalues 2.61 1.72 Proportion of variance (%) 52.1 34.4 Cumulative proportion (%) 52.1 86.5 Response measures First look duration 0.86 Total look duration 0.97 Number of looks 0.94 Time in proximity zone 0.91 Approach 0.93 2