AAUP-How to Diversify Faculty: The Current Legal Landscape

advertisement

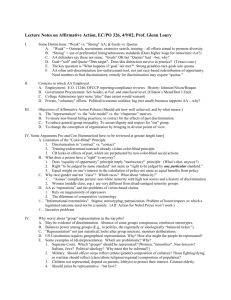

American Association of University Professors How to Diversify Faculty: The Current Legal Landscape Ann D. Springer AAUP Associate Counsel October 2002 I. Benefits of Diversifying A. A diverse faculty benefits students. Numerous studies and longstanding research shows that a diverse faculty and student body lead to great benefits in education. Not only does the law require that colleges and universities have no individual or systemic discrimination, but sound educational practice requires it. See, e.g., Chait, Richard P. and Trower, Cathy A., Faculty diversity: Too Little for Too Long, 104:4 Harvard Magazine 33 (March-April 2002); Turner, C.S.V., Diversifying the Faculty: A Guidebook for Search Committees, (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2002); Does Diversity Make a Difference? Three Research Studies on Diversity in College Classrooms, American Council on Education & American Association of University Professors (2000)(http://www.acenet.edu/programs/omhe/diversity.cfm) B. Discrimination claims are a big deal. A homogenous faculty not only fails to represent the diversity of views and experiences crucial to a broad education, but it leaves an institution vulnerable to damaging discrimination lawsuits. Such lawsuits are not only expensive for the institution, but also have big effects on faculty resources and morale. Having a diverse faculty limits such claims, both by students and faculty, and an easily observable commitment to diversity by the institution and the faculty in both policies and hires provides a strong defense to claims of discrimination. A diverse faculty, especially one supported by good diversity policies and commitments by the institution, is less likely to engage in the kind of discrimination that creates legal liability for the institution. C. Fears of "reverse discrimination" claims resulting from efforts to diversify are highly overrated. The vast majority of claims filed are "regular" discrimination claims, i.e. those filed regarding discrimination against minorities. Failure to diversify will leave an institution open to these claims. "Reverse discrimination" claims—allegations that diversification policies or actions take race into account in violation of the law—while a concern, are still a very small percentage of EEOC complaints. II. Law on Diversifying Faculty A. The law in this area is very unsettled. Factors like whether an institution is public or private, has a history of discrimination, and accepts federal funding all play a role. The law is essentially circular. To put it simply, the Constitution and federal statutes require that employers eliminate discrimination on the basis of race or sex. Employers can be sued under these statutes both for individual discrimination ("disparate treatment" of an individual) or for policies and practices that create widespread disparities in the number of women and minorities in the workplace (actions that have a "disparate impact" on minorities as a whole). In addition, some federal laws require employers to take explicit "affirmative action" to show how they will make their workplaces free from discrimination. Employers have thus adopted diversification plans (affirmative action plans) to create a more diverse workplace free from policies and practices that create a disparate impact, and to have tangible proof of their non-discrimination efforts. However, affirmative action plans and employment policies and decisions that explicitly take race into account in hiring can also implicate the constitutional requirement of equal treatment under the law, resulting in "reverse discrimination" claims. The courts have tried to deal with this conundrum by setting up restrictions and allowable justifications for such affirmative action (remedying past discrimination, societal benefits of diversity, narrowly tailoring efforts to make sure that they address only the particular problem and are short lived, etc.) but the result is a web of complex and interconnected laws and regulations that provide increasingly little clarity. B. The primary legal benchmarks in employment discrimination law are the standards under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution and Titles VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. C. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e et seq., makes it unlawful for an employer "to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with respect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, because of such individual's race, color, religion, sex, or national origin." This federal statute applies to faculty members and other employees of colleges and universities, private and public. D. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, prohibits race and national origin discrimination by recipients of federal financial assistance. Because most colleges and universities accept federal financial aid and other federal money, this applies to most institutions. (For the regulations issued by the Department of Education implementing Title VI, see 34 C.F.R. Part 100. < http://www.ed.gov/offices/OCR/regs/34cfr100.pdf>). Some courts have found that the standards for analysis of Title VI are the same as those under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. See "F" below. E. A presidential order known as Executive Order 11246 requires colleges and universities that receive federal contracts (a different, and higher standard than "federal aid") to take affirmative action as to race and national origin, among other factors. 1. The Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs in the U.S. Department of Labor has regulations governing affirmative action programs for government contractors. The regulations govern affirmative action plans and obligations for institutions contracting with the federal government for amounts equal to or greater than $50,000. (See 41 CFR Part 60-1, 60-2, <www.dol.gov/dol/allcfr/Title_41/ Chapter_60.htm>). While educational institutions are exempt from some of the requirements, the regulations still impose stringent tracking requirements mandating attention to affirmative action in hiring and promotion. 2. Affirmative Action: A good definition of affirmative action is included in the regulations implementing E.O. 11246. They define an affirmative action plan as "a set of specific and result-oriented procedures to which a contractor commits itself to apply every good faith effort. The objective of those procedures plus such efforts is equal employment opportunity. Procedures without effort to make them work are meaningless; and effort, undirected by specific and meaningful procedures, is inadequate.. . ." 41 CFR 60-2.10. (This definition goes on to require specific workplace analyses, set goals and timetables, which are requirements specific to federal contractors). a. An affirmative action plan should be a narrowly tailored program that considers race, gender, etc. as a factor in recruitment, hiring and promotion policies and practices to remedy the present effects of past discrimination and to diversify the workforce. (See AAUP Redbook, Affirmative Action in Higher Education (p. 193); Affirmative Action Plans (p. 201). F. The 14th Amendment to the Constitution provides that "[n]o State shall make or enforce any law which shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws." 1. This constitutional provision, and the standards the courts have developed to implement it, applies only to public institutions. However, some courts have stated that this standard is the same as the standard to be applied under Title VI, which would mean that the constitutional standard is applied to virtually all institutions, public and private. 2. Under the 14th Amendment, consideration of race or national origin in hiring or promotion decisions is subject to "strict scrutiny," which requires that policies be "narrowly tailored" to achieve a "compelling government interest." 3. One major area of debate is what constitutes a "compelling interest." Compelling interests recognized under the law have included remedying the present effects of past discrimination and the attainment of a diverse student body to further the "robust exchange of ideas" on campus. (See Justice Powell's opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978); Grutter v. Bollinger, 288 F.3d 732 (6th Cir. 2002)). a. Remediation of past discrimination: i. Involves remediation of the present effects of past discrimination at that institution, thus it requires an admission of guilt specific to that institution. See, e.g., Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200 (1995); City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S 469 (1989). ii. The courts have concluded that remediation of general social discrimination (rather than the individual discrimination by the challenged employer) is not a sufficiently compelling interest to justify racial classification remedies. See, e.g., Wygant v. Jackson Bd. Of Educ., 476 U.S. 267, 274 (1986); City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S 469 (1989). b. Diversity i. Based on the argument that a diverse faculty is an important part of the "robust exchange of ideas," and that an institution, and the faculty who help run it, must be able to decide "for itself on academic grounds, who may teach, what may be taught, how it shall be taught, and who may be admitted to study." Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 311-12 (1978)(quoting Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234 (1957)). ii. Used more frequently by colleges and universities because it is premised on a positive need for the consideration of race and national origin that contributes to the educational mission, and because it does not require institutions to admit to past discrimination. In light of current legal challenges, however, the legal justifications for programs based on diversity must be clearly articulated. An institution must be able to articulate how faculty diversity contributes to the learning environment and experience on campus. For more detailed discussion, see "The Educational Value of Diversity," 83 Academe 20 (Jan.-Feb. 1998). (a) Courts have generally frowned upon arguments relying upon race as a proxy for a particular point of view, because such arguments appear to be based on racial stereotypes and generalized assumptions. Courts have also failed to embrace the role model theory as a basis for faculty employment decisions, under which faculty of color in a variety of disciplines are seen as role models for underrepresented students of color. See, e.g., Adarand Constructors, Inc. v. Pena, 515 U.S. 200 (1995); City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S 469 (1989); Wygant v. Jackson Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. 267, 275-6 (1986); Taxman v. Board of Educ. of the Township of Piscataway, 91 F.3d 1547 (3rd Cir. 1996), cert. dismissed, 522 U.S. 1010 (1997). 4. Even if a compelling interest is shown, to pass constitutional muster an affirmative action plan must be "narrowly tailored." For an affirmative action program to be "narrowly tailored" under the law, the following factors must be considered: (1) the efficacy of alternative, "less intrusive" race-neutral approaches; (2) the extent, duration, and flexibility of race-conscious considerations; and (3) the burden on those who do not receive the benefit of any consideration of race. See, e.g., City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S 469 (1989); Wigand v. Jackson Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. 267 (1986). III. How to Diversify There are myriad ways, both large and small, to diversify the faculty. Institutions have tried many different approaches to diversifying within the parameters of the law. While some have been found problematic by the courts, others are considered both safe and effective. A. Some institutional diversity programs have been found somewhat problematic by the courts, although many of them still contain good elements, or could be easily retooled to address the courts' concerns. 1. Bonus Hire Programs: programs where a department is given an additional faculty position if it hires a minority candidate. a. University of Nevada v. Farmer, 930 P.2d 730 (1997), cert. denied, 523 U.S. 1004 (1998). The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review a faculty employment case in which the Nevada Supreme Court upheld the University's right to consider race as a factor to diversify its faculty. The plaintiff (Farmer) had been a finalist for position in the sociology department in 1991 when the University instead hired an African-American and paid him more than the posted salary range. At that time, only 1% of the University's faculty members were black, and the University maintained a "minority bonus program" that allowed a department to hire an additional faculty member if it first hired a minority. One year later, the sociology department filled the additional slot created by the minority bonus program by hiring the plaintiff. She was offered $7,000 less per year than the black male when he was hired. 2. Incentive Funds: Funds designed to provide incentives to departments to recruit and hire minorities; extra departmental money, salary assistance, etcetera. a. Such funds should be directed toward additional recruiting of minority faculty. However, to the extent they could be shown to actually directly influence individual hires they could run afoul of Title VII and the Constitution. b. There is one court that has explicitly considered this issue, and the decision is mixed. Honadle v. University of Vermont and State Agricultural College, 56 F. Supp. 2d 419 (D.Vt. 1999). The University of Vermont had a "faculty incentive fund" that provided grants for the hiring of minority faculty and faculty who will enhance "multi-cultural curricula." Departments did not know at the time of hire whether they had received a grant because applications weren't considered until later in the year, and funding was contingent on availability. A federal district court ruled that the fund, to the extent it functioned as a racially conscious inducement for departments to recruit minority faculty members, did not violate Title VII. However, the court noted that there was no evidence that the plan or anyone administering it dictated any hiring decisions. Had it been found that the funds had the effect of influencing the decision to hire a candidate on the basis of race, the plan would not have passed constitutional muster. 3. Voluntary/Mandatory Set Asides: Plans to hire a "quota" of minorities, or to set aside certain positions, have not been supported by the courts. See, e.g., City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 488 U.S 469 (1989); Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). a. The court in Honadle discussed the problem with this option as a distinction between "'inclusive' forms of affirmative action, such as recruitment and other forms of outreach, and 'exclusive' forms of affirmative action, such as quotas, set asides and layoffs." 56 F.Supp.2d at 428. b. Eg: Hill v. Ross, 183 F.3d 586 (7th Cir. 1999). When faced with a lawsuit by a male professor whose appointment to a tenure track position was blocked because the dean said that the department needed a certain amount of women to reach its target of 62%, the Seventh Circuit held that a state university may not require that each department's faculty mirror the sexual makeup of the pool of doctoral graduates in its discipline. 4. Special Protection for Minorities: Creating special protections for minorities once hired is also considered problematic. a. The Third Circuit found that race conscious layoff decisions were not acceptable even when the goal was to promote a public high school faculty's racial diversity. Taxman v. Board of Educ. of the Township of Piscataway, 91 F.3d 1547 (3d Cir. 1996), cert. dismissed, 522 U.S. 1010 (1997). (The Supreme Court granted certiorari in this case, but a coalition of civil rights groups, concerned that the unusual facts presented a bad test case for the Court, helped to arrange a settlement before it was heard). Plans for preferential promotions or salary increases for minorities would face the same problems. They would have to pass strict scrutiny, and unless designed to rectify specific and demonstrable past discrimination, would likely be struck down. 5. Race/Sex as a "plus" factor: Considering race or sex as one positive factor among many remains constitutional as a compelling factor under the diversity argument in Bakke. a. Constitutional standards would require such a plan to be narrowly tailored. A plan that considered race or sex as one of many factors would by its nature seem more flexible (one of the criteria for narrow tailoring), as it allows for varied weighting and consideration of a whole range of factors. b. Considering race or sex as one factor among many would probably pass Title VII. c. If race or sex were a sole factor however, it would violate both Title VII and the Constitution. i. See, e.g., Stern v. Trustees of Columbia Univ. in the City of New York, 131 F.3d 305 (2d Cir. 1997). The Second Circuit reversed a lower court and ordered a jury trial to review charges that Columbia University discriminated against an instructor because he was not of Hispanic descent. The plaintiff, who had taught Spanish and Portuguese at Columbia since 1978 and served as interim director of the University's Spanish language program for two years, was allegedly not seriously considered for the permanent directorship because he is a white male of Eastern European descent. The University claimed that although Stern was a finalist for the position, it chose another candidate based on qualifications, not bias. The person who was hired is described in court papers as an American of Hispanic descent. Stern alleged that this individual had not yet earned his PhD, had less teaching experience and had written less extensively than the plaintiff, and was not proficient in Portuguese. The search committee at Columbia asked each of three finalists (including these two) to teach "tryout" classes, and found that the candidate they selected "mesmerized" the class while the plaintiff's teaching was weak. B. There are many good, legal approaches that institutions can and should implement to diversify the faculty. 1. Recruiting/Outreach a. Courts have found race conscious recruiting acceptable under all of the different standards. Taking steps to increase the pool of qualified applicants increases chances for diverse candidates, and exposes the institution to a broader pool of talent. See, e.g., Duffy v. Wolle, 123 F.3d 1026 (8th Cir. 1997); Hill v. Ross, 183 F.3d 586 (7th Cir. 1999). i. Advertise Widely: advertise in journals and periodicals that make special efforts to reach minority faculty and graduate students. Vacancy announcements can also be sent to faculty members or graduate students at minority-serving institutions, organizations that work on minority issues, components within organizations such as minority caucuses in national scholarly associations, and personal contacts in the field who are likely to know promising graduate students or other potential applicants. Consult with minority faculty members on campus for their views on outreach. ii. Position Description: Realistically reflect the full range of skills and knowledge needed. Criteria for consideration can include factors like demonstrated ability to work with diverse students and colleagues, or experience with a variety of teaching methods or curricular perspectives. Rigid criteria that are not absolutely necessary for the position should be avoided, because they might exclude promising candidates from less traditional backgrounds who could make substantial contributions to the institution if given the opportunity. In addition, tying the description closely to the real range of skills needed is a strong argument against claims that race or sex was impermissibly considered in hiring. 2. Search Committees a. Search committees are often the weak link in discrimination lawsuits. It is unfair and unrealistic to expect faculty committees to understand the nuances of the issues and legal restraints in this area without information and support from the administration and its policies. Even well meaning people often misunderstand affirmative action and can unwittingly say or do things that cause candidates to feel they are being discriminated against or misrepresent the position or the institution's commitment to diversity. b. Briefing search committees ahead of time is a benefit to the committee and to the institution. Committees should receive guidance about reaching out to the complete pool of qualified applicants, subtle forms of discrimination that can creep into the process, ways to evaluate candidates in a way that values diversity, and what they should and shouldn't say and promise. They should also receive materials about institutional commitment to diversity and its educational benefits. c. Pay attention to whether candidates' graduate schools are ranked, and if so, how minority serving institutions and programs fare in that ranking. Make sure that the ranking of minority institutions accurately reflects the strength of their programs and the advantages they offer, and does not reflect any prejudice or discrimination. 3. Retention: a. Mentoring: Increase formal and informal efforts to reach out to new hires, integrate them into the social and professional life of the department and the university community, and provide them guidance on research, teaching, and the tenure and promotion process. b. Criteria for promotion and tenure: Make sure that there aren't subtle discriminations built into the criteria for promotion. i. Areas of study: Are all areas of study weighted equally? Are ethnic studies treated differently or undervalued in some way? ii. Service commitment: Be sure that minority faculty members receive credit for the various ways in which they provide service to the university through service on committees, mentoring and tutoring students, etc. Remember that minority faculty members often have demands placed upon them that differ from the expectations placed upon white faculty members. iii. Student Evaluations: Where issues of race and ethnicity are explicitly raised in classes, be aware of potential student reactions and prejudices when considering the weight to assign to student course evaluations. IV. Resources Following is a list of resources helpful in this area: Affirmative Action in Higher Education: A Report by the Council Committee on Discrimination, AAUP Policy Documents & Reports 193, 194 (9th ed., 2001). Affirmative-Action Plans: Recommended Procedures for Increasing the Number of Minority Persons and Women on College and University Faculties, AAUP Policy Documents & Reports 201 (9th ed., 2001). Alger, Jonathan R., Minority Faculty and Measuring Merit: Start by Playing Fair, 84 Academe 71 (July-Aug. 1998). Alger, Jonathan R., Unfinished Homework for Universities: Making the Case for Affirmative Action, 54 Washington University Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law 73 (1998). Alger, Jonathan R., When Color-Blind is Color-Bland: Ensuring Faculty Diversity in Higher Education, 10 Stanford Law & Policy Review 191 (Spring 1999). Antonio, A.L., Faculty of Color and Scholarship Transformed: New Arguments for Diversifying Faculty, 3 Diversity Digest No. 2, at 6-7 (2000). Blackshire-Belay, C., The Status of Minority Faculty Members in the Academy, 84 Academe 32-35 (July-Aug. 1998). Chait, Richard P. and Trower, Cathy A., Faculty diversity: Too Little for Too Long, 104:4 Harvard Magazine 33 (March-April 2002) (available on the web at <http://www.harvardmagazine.com/on-line/030218.html>) Coleman, Arthur L., Diversity in Higher Education: A Strategic Planning and Policy Manual, The College Board (2001). Diversity Web: http://www.diversityweb.org/ (University of Maryland & Association of American Colleges and Universities). Does Diversity Make a Difference? Three Research Studies on Diversity in College Classrooms, American Council on Education & American Association of University Professors (2000). Getting Results: Affirmative Action Guidelines for Searches to Achieve Diversity, Pennsylvania State University: The Affirmative Action Office (1997). Knowles, M.F. and Harleston, B.W., Achieving Diversity in the Professoriate: Challenges and Opportunities, American Council on Education (1997). Minorities in Higher Education, American Council on Education (an annual report). Moody, JoAnn, Retaining Non-Majority Faculty - What Senior Faculty Must Do, 10 The Department Chair 1, Anker Publishing Company (Summer 1999). Smith, Daryl G., How to Diversify the Faculty, 86 Academe 48 (Sep.-Oct. 2000). Smith, Daryl G., Wolf, Lisa E., & Busenberg, Bonnie E., Achieving Faculty Diversity: Debunking the Myths (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 1996). Springer, Ann, Update on Affirmative Action in Higher Education: A Current Legal Overview (maintained on AAUP's Website <www.aaup.org/Issues/AffirmativeAction/aalegal.htm> Turner, C.S.V., Diversifying the Faculty: A Guidebook for Search Committees (Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2002). Turner, C.S.V. & Myers, S.M., Jr., Bittersweet Success: Faculty of Color in Academe, Allyn & Bacon (1999). Turner, C.S.V., New Faces, New Knowledge, 86 Academe 34 (Sep.-Oct. 2000). University of Wisconsin-Madison: Search Handbook, <http://www.ohr.wisc.edu/polproced/srchbk/sbkmain.html> Whitman, Robert S., Affirmative Action on Campus: The Legal and Practical Challenges, 24 Journal of College and University Law 637 (Spring 1998). American Association of University Professors, 1012 Fourteenth Street, NW, Suite #500; Washington, DC 20005 202-737-5900 Fax: 202-737-5526 AAUP Home Page | Contact Us