Bench Notes: Joint Criminal Enterprise

advertisement

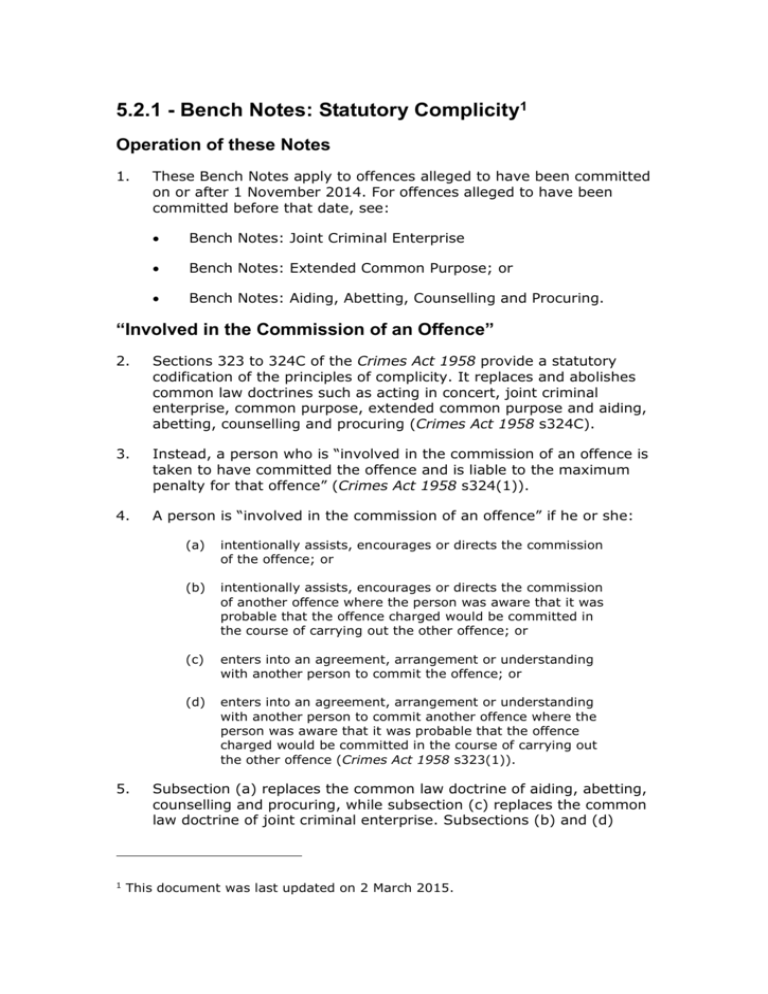

5.2.1 - Bench Notes: Statutory Complicity1 Operation of these Notes 1. These Bench Notes apply to offences alleged to have been committed on or after 1 November 2014. For offences alleged to have been committed before that date, see: Bench Notes: Joint Criminal Enterprise Bench Notes: Extended Common Purpose; or Bench Notes: Aiding, Abetting, Counselling and Procuring. “Involved in the Commission of an Offence” 2. Sections 323 to 324C of the Crimes Act 1958 provide a statutory codification of the principles of complicity. It replaces and abolishes common law doctrines such as acting in concert, joint criminal enterprise, common purpose, extended common purpose and aiding, abetting, counselling and procuring (Crimes Act 1958 s324C). 3. Instead, a person who is “involved in the commission of an offence is taken to have committed the offence and is liable to the maximum penalty for that offence” (Crimes Act 1958 s324(1)). 4. A person is “involved in the commission of an offence” if he or she: 5. 1 (a) intentionally assists, encourages or directs the commission of the offence; or (b) intentionally assists, encourages or directs the commission of another offence where the person was aware that it was probable that the offence charged would be committed in the course of carrying out the other offence; or (c) enters into an agreement, arrangement or understanding with another person to commit the offence; or (d) enters into an agreement, arrangement or understanding with another person to commit another offence where the person was aware that it was probable that the offence charged would be committed in the course of carrying out the other offence (Crimes Act 1958 s323(1)). Subsection (a) replaces the common law doctrine of aiding, abetting, counselling and procuring, while subsection (c) replaces the common law doctrine of joint criminal enterprise. Subsections (b) and (d) This document was last updated on 2 March 2015. replace the principles of extended common purpose with a new form of liability based on recklessness for secondary offences, which extend liability under subsections (a) and (c) respectively. Derivative liability 6. Liability under Crimes Act 1958 s324 is derivative. Secondary liability on the basis of complicity only attaches if an offence “is committed”. This requires proof in the trial of a secondary party, that the offence was committed. However, it is not necessary that the principal offender (or any other offenders) be prosecuted or found guilty of that offence (Crimes Act 1958 s324A). 7. This requires the prosecution to prove that a principal offender committed the relevant criminal acts with the necessary criminal intention (R v Jensen and Ward [1980] VR 194). 8. As discussed under Mentally Impaired Parties below, it is likely that the defence of mental impairment operates to excuse the principal offender’s liability but does not affect whether the offence “is committed”. 9. In contrast, defences such as self-defence or duress are inconsistent with a conclusion that the offence “is committed”. Where the jury finds, in the trial of the secondary party, that the principal offender acted under duress or in self-defence, then the jury must find the secondary party not guilty of committing the offence. This does not prevent other bases of liability, such as conspiracy or incitement to commit the offence, where those inchoate offences are appropriate. 10. If the accused (that is, the secondary party) and the principal offender are tried together, and the evidence against them is the same, the accused generally cannot be found guilty unless the principal offender is also found guilty (Osland v R (1998) 197 CLR 316). 11. However, different verdicts between a principal offender and a secondary party will not always be inconsistent. For example, there may be sufficient evidence to prove that the secondary party assisted someone to commit the principal offence, but insufficient evidence to establish the identity of the principal offender (Osland v R (1998) 197 CLR 316; R v King (1986) 161 CLR 423). 12. Evidence that another person has been convicted is not admissible against the accused (R v Kirkby [2000] 2 Qd R 57; Evidence Act 2008 s91). 13. In some cases, the jury may be satisfied that the accused either committed the offence himself or herself or is liable as a secondary party, but cannot determine which. In that situation, the jury is entitled to convict the accused (Crimes Act 1958 s324B). 14. This principle extends to the scenario where there are several accused tried together and the jury cannot determine which was the principal offender and which are “involved in the commission of the offence”, i.e. secondarily liable (see R v Lowery & King (No 2) [1972] VR 560; R v Phan (2001) 53 NSWLR 480; R v Clough (1992) 28 NSWLR 396; R v Mohan [1967] 2 AC 187). Intentionally assisting, encouraging or directing 15. Under subsection (a) of the definition of “involved in the commission of an offence”, the prosecution must prove that the accused either: Intentionally assisted; Intentionally encouraged; or Intentionally directed the commission of the offence. Assistance, encouragement and direction 16. While there is not yet any authority on the point, it is likely that the words “assists, encourages or directs” will be treated as ordinary English words and that the meaning and operation of the terms will be a question of fact for the jury. 17. The words “assists” and “encourages” reflect the common law complicity liability of “aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring” an offence, which was defined as intentionally assisting or encouraging the principal offender to commit that offence (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). 18. At common law, it was not necessary (or sufficient) to show that the accused exerted control over the principal offender. In cases of assisting or encouraging, the principal offender would have acted voluntarily, breaking the causal link between the accused’s alleged control of the principal offender and the commission of the offence (R v Franklin (2001) 3 VR 9). It is likely that this is equally true for complicity under the Crimes Act 1958. 19. The accused also does not need to have reached an agreement with the principal offender about the commission of the crime, which is a separate pathway to complicity liability covered by Crimes Act 1958 ss 323(1)(c) and (d). This was also true of aiding, abetting, counselling or procuring at common law, where the accused merely needed to have provided encouragement or assistance to the principal offender (R v Oberbilig [1989] 1 Qd R 342; R v Nguyen [2010] VSCA 23). 20. Subsection (a) of the definition of involvement removes the distinctions which existed at common law between liability as an accessory before the fact and as a principal in the second degree. The jury will instead look at all of the accused’s conduct, leading up to and at the time of the alleged offence to determine whether the accused intentionally assisted, encouraged or directed the commission of the offence. 21. The definition also omits the third form of aiding and abetting at common law, which consisted of intentionally conveying assent to and concurrence in the commission of the crime. As explained by Ormiston JA in R v Makin (2004) 8 VR 262, this was likely a form of encouragement, and so it did not need to be separately described (see also R v Phan (2001) 53 NSWLR 480; R v Al Qassim [2009] VSCA 192). 22. Where it is alleged that the accused “assisted” the principal offender, it is not necessary to prove that the principal offender was aware of the accused’s assistance (R v Lam & Ors (Ruling No 20) (2005) 159 A Crim R 448). 23. Similarly, where it is alleged that the accused “encouraged” the principal offender, it is not necessary to prove that the primary offence was in fact encouraged (Crimes Act 1958 s323(2)). See Effect of encouragement need not be determined below. Presence at the commission of the crime 24. The Crimes Act 1958 abolishes any common law requirement that a secondary party must be physically present at the time of the commission of the offence (Crimes Act 1958 s323(3)(a)). Physical presence is merely relevant as evidence to support a finding of assistance, encouragement or direction. 25. Mere presence at a crime is not sufficient by itself to found liability (R v Al Qassim [2009] VSCA 192; R v Makin (2004) 8 VR 262; R v Lam (2008) 185 A Crim R 453; R v Nguyen [2010] VSCA 23; Al-Assadi v R [2011] VSCA 111). 26. This is because, to be liable, a person must have assisted, encouraged or directed the principal offender in some way. A person who is simply present at the commission of a crime will usually not have offered such assistance or encouragement (see R v Makin (2004) 8 VR 262). 27. In some cases, however, the accused may assist or encourage the commission of a crime by being present. For example, by choosing to be present at the crime scene, the accused may provide moral support to the principal offender, or demonstrate a willingness to assist if required. Similarly, if the criminal offending was designed to be a public spectacle (such as an illegal prize fight), and drew support from the presence of observers, the accused’s presence may be seen as having provided encouragement to the principal offender (R v Lowery & King (No 2) [1972] VR 560; R v Conci [2005] VSCA 173; R v Panozzo [2007] VSCA 245; R v Coney (1882) 8 QBD 534). 28. For the accused’s presence to constitute assistance or encouragement, he or she must have done something more than simply be at the scene of the crime. The accused must, at some point, have said or done something which showed that he or she was linked in purpose with the principal offender, and thus contributed to the crime (R v Al Qassim [2009] VSCA 193; R v Nguyen [2010] VSCA 23). 29. The accused must have done something of a kind that can reasonably be seen as intentionally adopting and contributing to what was taking place in his or her presence (Al-Assadi v R [2011] VSCA 111). 30. Where it is alleged that the accused assisted or encouraged by being present at the scene of the crime, the judge should therefore tell the jury that mere presence is not sufficient. The judge should make clear that something more is required (R v Al Qassim [2009] VSCA 193; Al-Assadi v R [2011] VSCA 111). 31. The judge should clearly identify the additional matters beyond mere presence said to constitute assistance or encouragement (R v Al Qassim [2009] VSCA 193). 32. In determining whether the accused’s presence assisted or encouraged the commission of the offence, the accused’s conduct relating to the offence should be viewed as a whole. Things that the accused said or did prior to the commission of the offence may warrant the conclusion that the accused’s presence made him or her complicit in the offence, by helping or encouraging the principal offender to commit the crime (R v Al Qassim [2009] VSCA 192). Effect of encouragement need not be determined 33. Crimes Act 1958 s323(2) provides that: In determining whether a person has encouraged the commission of an offence, it is irrelevant whether or not the person who committed the offence in fact was encouraged to commit the offence. 34. This preserves the position which existed at common law that it was not necessary to prove that the principal offender was aware of the accused’s encouragement, nor was it necessary to prove that the principal offender was actually encouraged by the accused’s words or actions (see R v Lam & Ors (Ruling No 20) (2005) 159 A Crim R 448). 35. However, it is likely that in “encouragement” cases the prosecution must still prove that the encouragement was communicated to the principal offender in circumstances such that s/he could have been aware of that encouragement (See R v Lam & Ors (Ruling No 20) (2005) 159 A Crim R 448). Failure to Act 36. Ordinarily, the fact that the accused failed to act in a particular way will not be sufficient to prove that s/he assisted or encouraged the principal offender to commit the crime (R v Russell [1933] VLR 59). 37. However, where the accused is under a legal or ethical duty to act, a failure to do so may be evidence of encouragement or assent to the offending (see, e.g., R v Russell [1933] VLR 59; Ex parte Parker: Re Brotherson (1957) SR(NSW) 326). 38. The Crimes Act 1958 recognises, in section 323(3), that a person may be involved in the commission of an offence by “act or omission”. 39. A duty to act may arise where the accused is in loco parentis to the victim (R v Russell [1933] VLR 59; R v Clarke and Wilton [1959] VR 645). 40. Where a person has a duty to act, s/he may be seen to have assisted or encouraged the principal offender if s/he fails to offer any protest to his/her conduct, or fails to offer any effective dissent (R v Russell [1933] VLR 59). Intention 41. The prosecution must prove that D intentionally assisted, encouraged or directed the commission of the offence (Crimes Act 1958 s323(1)(a)). 42. The accused’s state of mind must be assessed at the time s/he gave the relevant assistance, encouragement or direction rather than at the time of the offence (White v Ridley (1978) 140 CLR 342). 43. The state of mind the prosecution must prove in relation to a secondary party differs from the state of mind required for the principal offender: For the principal offender, the prosecution must prove that, at the time of the offence, s/he acted with the state of mind necessary for that offence; For the secondary party, the prosecution must prove that, at the time he or she offered assistance, encouragement or direction to the principal offender, he or she intended to assist, encourage or direct him or her (R v Stokes & Difford (1990) 51 A Crim R 25; R v Lam & Ors (Ruling No 20) (2005) 159 A Crim R 448). 44. At common law, proof of an intention to assist or encourage required the prosecution to prove that the accused knew of, or believed in, the essential circumstances that establish the principal offence (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). It is likely that the same principle applies under the Crimes Act 1958. 45. The “essential circumstances” of an offence are the facts that will go to satisfying the elements of the offence (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). 46. For mens rea offences, the “essential circumstances” include the principal offender’s state of mind (R v Stokes & Difford (1990) 51 A Crim R 25; R v Lam & Ors (Ruling No 20) (2005) 159 A Crim R 448; R v Phan (2001) 53 NSWLR 480).2 47. Where the offence requires a particular result to have been caused (e.g., death or serious injury), the accused does not need to know or intend that this result will be achieved. It is sufficient if s/he knew or intended that: the principal offender was going to commit the acts which ultimately caused that result (but not that those acts would in fact cause that result), and the principal offender would have the requisite state of mind when committing those acts (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473; R v Stokes & Difford (1990) 51 A Crim R 25; Likiardopoulos v R [2010] VSCA 344). 48. The jury must consider what the accused knew at the time s/he assisted, encouraged or directed the principal offender, rather than at the time the principal offender committed the offence (R v Stokes & Difford (1990) 51 A Crim R 25). 49. The accused does not need to know that the principal offence is a criminal offence. It is sufficient if s/he intentionally assisted, encouraged or directed the conduct which constituted that offence (Crimes Act 1958 s323(3)(b). See also Johnson v Youden [1950] 1 KB 544; Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). 50. For the purpose of attributing criminal liability, an employee’s knowledge cannot necessarily be imputed to an employer (Ferguson v Weaving [1951] 1 KB 814). 51. The accused must have actual knowledge or belief of the essential circumstances. It is not sufficient that he or she should have known of those circumstances, or failed to inquire about them (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). 52. However, the failure of a person to make inquiries about the circumstances may be evidence that he or she was aware of the For strict liability offences, while the accused must know the essential circumstances of the offence, s/he does not need to have any awareness of the principal offender’s state of mind (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). 2 relevant facts (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). 53. The accused must have intended to assist, encourage or direct the principal offender to commit the offence charged.3 It is therefore not sufficient for the prosecution to prove that: The accused had a general intention to assist crime (R v Clarkson [1971] 3 All ER 344; Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473; R v Tamme [2004] VSCA 165); or That the accused intended to assist or encourage a significantly different offence (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473; Chai v R (2002) 187 ALR 436; R v Conci [2005] VSCA 173). 54. Even if the principal offence is one that does not require the principal offender to have had a particular state of mind when it was committed (i.e., a strict liability offence), the accused must still be shown to have intended to assist, encourage or direct the principal offender to commit that offence (Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473; R v Tamme [2004] VSCA 165; R v Dardovski 18/5/1995 Vic CCA). Agreement, Arrangement or Understanding 55. Subsection (c) of the definition of “involved in the commission of an offence” covers the situation where the accused “enters into an agreement, arrangement or understanding with another person to commit the offence” (Crimes Act 1958 s323(1)(c)). 56. This replaces the common law principles such as acting in concert, common purpose and joint enterprise. 57. Offending as part of a group therefore requires proof of three elements: i) That two or more people reached an agreement to commit an offence that remained in existence at the time the offence was committed; ii) That, in accordance with the agreement, one or more parties to the agreement performed all of the acts necessary to commit the offence charged, in the circumstances necessary for the commission of that offence; and iii) That the accused had the state of mind required for the commission of the relevant offence at the time of entering into the agreement (Crimes Act 1958 s323(1)(c), s324(1)-(2)). See also R v Clarke and Johnstone [1986] VR 643; Johns v R (1980) 143 CLR 108; McAuliffe v R (1995) 183 CLR 108; R v However, see Divergence (below) for a discussion of liability on the basis of assisting, encouraging or directing a different offence from the one charged. 3 Taufahema [2007] HCA 11; Likiardopoulos v R [2010] VSCA 344; Arafan v R [2010] VSCA 356). 58. At common law, offending as part of a group required proof of an additional element that the accused participated in the joint enterprise in some way. It is likely that this requirement no longer applies to complicity under Crimes Act 1958 s323(1)(c). Instead, group offending is treated as a form of completed conspiracy. Formation of agreement 59. For the first element to be met, the prosecution must prove: That the accused reached an agreement, arrangement or understanding with others to commit the offence; and That the agreement, arrangement or understanding remained in existence at the time the offence was committed (R v Clarke & Johnstone [1986] VR 643; R v Lao & Nguyen (2002) 5 VR 129). 60. As at common law, the agreement need not be express but may also be an “arrangement or understanding”. It may be inferred from the surrounding circumstances (R v Tangye (1997) 92 A Crim R 545; R v Clarke and Wilton [1959] VR 645; R v Jensen and Ward [1980] VR 196; Guthridge v R [2010] VSCA 132). 61. The agreement must be to commit the criminal offence charged. This element will not be satisfied if the accused agreed to pursue some form of wrongdoing that is not criminal, or to pursue a different offence (See R v Taufahema (2007) 228 CLR 232).4 62. The parties to the agreement do not need to have realised that their acts would be criminal. This element will be satisfied if they agreed to perform acts which, in fact, are criminal (Crimes Act 1958 s323(3)(b); Osland v R (1998) 197 CLR 316; R v Cox & Ors [2005] VSC 255). 63. The parties do not need to have precisely agreed on the scope of the agreement. This element will be satisfied if they shared an agreement, arrangement or understanding to commit a particular criminal act, even if they disagreed on the purpose of that act (Gillard v R (2003) 219 CLR 1; R v Zappia (2002) 84 SASR 206; c.f. Collie, Kranz & Lovegrove v R (1991) 56 SASR 302).5 However, see Divergence (below) for a discussion of liability on the basis of an agreement, arrangement or understanding to commit a different offence from the one charged. 4 The courts have noted that this can produce an agreement that is narrower than the purpose of any given party (Gillard v R (2003) 219 CLR 1; R v Zappia (2002) 84 SASR 206; c.f. Collie, Kranz & Lovegrove v R (1991) 56 SASR 302). 5 64. Where the prosecution alleges an agreement, arrangement or understanding between more than two accused, it may not be necessary to prove that all of the accused were parties to the same agreement. It may be sufficient for the prosecution to prove that there are relationships between the various accused which form a chain of agreements over a common subject matter (see, e.g., R v Lao & Nguyen (2002) 5 VR 129). Timing of agreement 65. The agreement need not have been formed far in advance of the offence. It may have been formed moments before the offence was committed (R v Tangye (1997) 92 A Crim R 545; R v Jensen and Ward [1980] VR 196; Guthridge v R [2010] VSCA 132). 66. The fact that two people spontaneously decided to pursue the same course of action does not necessarily prove that they were acting pursuant to an agreement to commit a particular crime (R v Taufahema (2007) 228 CLR 232). 67. Two or more people may form an agreement that gives one of them the right to decide whether to commit a criminal act on any given occasion. Such an agreement will make all of the parties liable, even though they are not certain when the act will be committed (Miller v R (1980) 32 ALR 321). Mentally Impaired Parties 68. At common law, a person who was mentally impaired because s/he did not realise that his/her acts were wrongful may still have been able to participate in an agreement to commit an offence. This allowed a court to find that such an agreement existed in determining the liability of secondary parties, as long the mentally impaired person was able to understand the nature and quality of the act to be performed (Matusevich v R (1977) 137 CLR 633; Osland v R (1998) 197 CLR 316). 69. Although it is not entirely clear, the better view appears to be that the same result follows under the Crimes Act 1958. While liability for complicity under the Act is derivative, the nature of the special verdict of not guilty because of mental impairment makes it consistent with a finding that the offence was committed. 70. The doctrine of innocent agent may also apply if the accused persuades a mentally impaired person to commit an offence (Matusevich v R (1977) 137 CLR 633). Cancellation or Completion of Agreement 71. The prosecution must prove that the agreement had not been called off before the offence was completed (R v Heaney & Ors [1992] 2 VR 531). 72. In some cases, the acts agreed to by the parties may be completed without achieving the intended purpose of the agreement. In this situation, a party to the agreement will not be liable for the later completion of that purpose by any of the other parties to the agreement (unless s/he agreed to such a variation of the original agreement) (R v Heaney & Ors [1992] 2 VR 531). Commission of the agreed offence 73. As noted above in Derivative Liability, proof of complicity requires proof that a person committed the offence charged. 74. In the context of group offending, the prosecution must also prove that the commission of the offence occurred in accordance with, or within the scope of, the agreement, arrangement or understanding. Conduct outside the scope of the agreement 75. At common law, an issue often arose whether the crime committed was within the scope of the agreement formed between the parties (see, e.g. R v Jensen and Ward [1980] VR 196; R v PDJ (2002) 7 VR 612; R v Anderson [1966] 2 QB 110; R v Heaney & Ors [1992] 2 VR 531). 76. The scope of the agreement must be determined by considering the subjective beliefs of the participants at the time the agreement was formed, or at the time the parties agreed to vary the original agreement (R v Johns (1980) 143 CLR 108; R v McAuliffe (1995) 183 CLR 108). 77. The scope of the agreement includes any contingencies that are planned as part of the agreed criminal enterprise (R v Becerra (1976) 62 Cr App R 212). 78. The liability of the accused is based on his/her authorisation (express or implied) of the criminal acts. Even if the accused did not believe that those acts were likely to be committed, s/he will be liable if they were within the scope of the agreement (Johns v R (1980) 143 CLR 108; Chan Wing-Siu v R [1985] AC 186; Britten v R (1988) 49 SASR 47). 79. In some cases, the parties will have differed in their understanding of how the agreed crime was to be carried out, leading to arguments that the accused had not agreed to participate in the particular offence that was committed. In such cases, the jury must consider whether the use of the means adopted placed the offence outside the scope of the agreement, or alternatively, whether the use of those means was no more than an incident of carrying out the common agreement (Varley v R (1976) 12 ALR 347; R v Heaney & Ors [1992] 2 VR 531). 80. Where the agreement involves the use of violence, the jury may need to consider whether the perpetrator acted outside the scope of the agreement by unexpectedly using a weapon. This will depend on the facts of the case, the understanding of the parties, and the difference between the weapon used and the manner of violence intended (see Varley v R (1976) 12 ALR 347; R v Anderson [1966] 2 QB 110; Markby v R (1978) 140 CLR 108; Wooley v R (1989) 42 A Crim R 418; R v Heaney & Ors [1992] 2 VR 531). 81. Under the Crimes Act 1958, the focus is on whether the accused agreed, arranged or had an understanding with another person to commit the offence charged. If the offence committed varies from the offence agreed, then the case may be one of divergence (see below) and dealt with under subsections (b) or (d) of the definition, as appropriate. Accused’s mental state 82. As at common law, the prosecution must prove that at the time of entering the agreement, the accused had the state of mind required for the commission of the offence (Osland v R (1998) 197 CLR 316; Likiardopoulos v R [2010] VSCA 344). Divergence 83. Subsections (b) and (d) of the definition of “involved in the commission of an offence” address the situation where there is divergence between the offence originally assisted, encouraged, directed or agreed to, and the offence carried out. 84. In those situations, the accused will be liable for the new offence if he or she: intentionally assisted, encouraged or directed another offence; or entered into an agreement arrangement or understanding to commit another offence, and was aware that it was probable that the offence charged would be carried out in the course of committing the other offence (Crimes Act 1958 s323(1)(b) and (d)). 85. Subsection (d) is more limited than the common law doctrine of extended common purpose. Under that doctrine, it was sufficient for the prosecution to prove that the accused foresaw the possibility that the other offence would be carried out (Johns v R (1980) 143 CLR 108; McAuliffe v R (1995) 183 CLR 108; Hartwick, Clayton and Hartwick v R (2006) 231 ALR 500; R v Hartwick, Clayton and Hartwick (2005) 14 VR 125). 86. On the other hand, subsection (b) extends liability compared to the common law of “aiding, abetting, counselling and procuring”, which did not include liability for a different offence that the accused knew would probably occur during the course of the assisted or encouraged offence. 87. While these sections have not yet been interpreted, it is likely, as a matter of statutory interpretation, that the word “probable” is an ordinary English word and it is a matter for the jury to give the word meaning. If necessary, a judge may suggest that “likely” is an acceptable synonym (see, e.g. Crabbe v R (1985) 156 CLR 464). If the jury requires further guidance, it may be permissible to explain that the word “probable” is used in contrast to what is merely “possible”. When directing the jury, the judge should not equate the word “probable” with a “balance of probabilities” test. Withdrawal 88. A person is not involved in the commission of an offence if he or she withdraws from the offence (Crimes Act 1958 s324(2)). The Act does not codify the law of withdrawal, and the common law on this topic is preserved (Crimes Act 1958 Notes to s324(2) and s324C). 89. At common law, a person is not responsible for the acts of other parties to an agreement if s/he withdrew from the agreement prior to its completion (R v Lowery & King (No 2) [1972] VR 560). Under the Crimes Act 1958, withdrawal may be relevant to both group offending and also to complicity on the basis of assisting, encouraging or directing an offence. 90. The withdrawal must ordinarily have been expressly communicated to the other members of the enterprise. However, in exceptional circumstances it may be possible for an accused to have implicitly withdrawn from the agreement (White v Ridley (1978) 140 CLR 342).6 91. The withdrawal must be accompanied by all action the accused can reasonably take to undo the effect of his/her previous encouragement or assistance. This may include informing the police (White v Ridley (1978) 140 CLR 342; R v Tietie (1988) 34 A Crim R 438; R v Jensen and Ward [1980] VR 196). 92. An accused who seeks to withdraw from an agreement must make a timely and effective withdrawal. An accused will not escape liability merely by leaving the scene shortly before the offence is completed, or by attempting to withdraw when it is too late to stop the offence (White v Ridley (1978) 140 CLR 342; R v Whitehouse [1941] 1 DLR 683; R v Rook [1993] 1 WLR 1005). For example, where there is a spontaneous agreement to assault another person, an accused may be able to withdraw by ceasing to fight and walking away without expressly communicating to others involved in the assault (R v Mitchell and King (1998) 163 JP 75; R v O’Flaherty, Ryan and Toussaint [2004] 2 Cr App R 20). 6 93. Similarly, a person is not taken to have withdrawn from an agreement merely because s/he has private feelings of regret, or wishes that s/he could stop the offence (R v Lowery & King (No 2) [1972] VR 560). 94. Where the accused has set in motion a chain of events leading to the commission of an offence, any attempts to withdraw from participation must be capable of effectively stopping the offending (White v Ridley (1978) 140 CLR 342). 95. In some cases, the accused may reasonably believe that once s/he withdraws from the agreement, the other members will not pursue the original criminal act. In those circumstances, the accused may not need to take any additional steps beyond countermanding his/her original instructions or agreement (R v Truong NSW CCA 22/06/1998). 96. It is usually more difficult to withdraw from an agreement at the time of the offending than beforehand. Withdrawal at the time of the offending will usually require greater conduct to undo the effect of the previous agreement (see R v Becerra (1976) 62 Cr App R 212). 97. It is not necessary to consider the issue of withdrawal using principles of causation. While a principal who continues to offend despite the timely withdrawal from the agreement by other parties may be treated as an intervening cause, it is not necessary to do so. Such an approach is likely to lead to confusion (White v Ridley (1978) 140 CLR 342; R v Tietie (1988) 34 A Crim R 438; R v Menniti [1985] 1 Qd R 250). 98. The issue of withdrawal only needs to be addressed if the defence has pointed to some evidence that shows that the accused unequivocally countermanded or revoked his/her previous agreement. The prosecution will then bear the onus of disproving this withdrawal (White v Ridley (1978) 140 CLR 342; R v Croft [1944] KB 295; R v Rook [1993] 1 WLR 1005). Availability of statutory complicity 99. A person may be liable for being involved in the commission of an offence in relation to both indictable and summary offences (Crimes Act 1958 s324(1)). 100. At common law, it was recognised that secondary liability could be impliedly excluded for some offences (Mallan v Lee (1949) 80 CLR 198; Giorgianni v R (1985) 156 CLR 473). 101. For offences committed after 1 November 2014, the question will be whether Crimes Act 1958 s324 is impliedly excluded. 102. The section only expressly excludes one class of offence. Under section 324(3), liability is not imposed “on a person for an offence that, as a matter of policy, is intended to benefit or protect that person” (Crimes Act 1958 s324(3)). 103. For example, a person under the age of 16 is not able to be involved with the commission of the offence of sexual penetration of him/herself (see, e.g., R v Whitehouse [1977] QB 868). 104. In addition, the beneficiary of a family violence restraining order cannot be prosecuted for assisting or encouraging the contravention of that order (see Family Violence Protection Act 2008 s125). 105. The law recognises that a person cannot attempt to conspire or attempt to be a secondary party to an offence (whether under the principles of statutory complicity or common law complicity) (Franze v R [2014] VSCA 352). 106. Conversely, it is possible for a person to be a secondary party to an attempted offence. This occurs, for example, when the person enters into an agreement to complete an offence and that agreement only produces an attempt at the contemplated offence. The distinction lies between a joint attempt, which is legally possible, and an attempt to agree, which is not (Franze v R [2014] VSCA 352).