Reflexes

advertisement

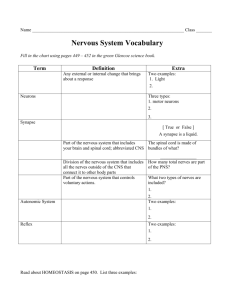

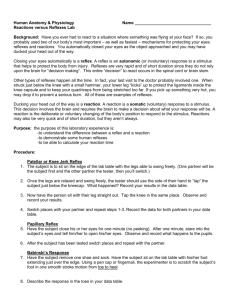

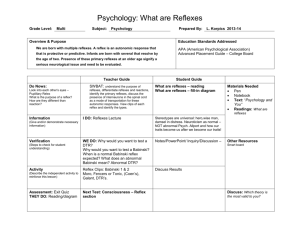

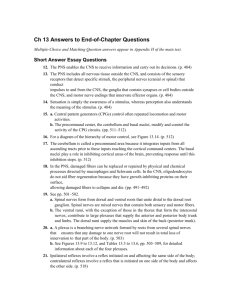

Reflexes: A Nerve Whacker Why does a doctor test my reflexes when I have a check up? What other reflex actions do we have? How do they protect us? Which reflexes can we control more than others ? If you could design new reflexes for yourself, what would they be? Connections 1. What other reflex actions do we have? How do they protect us? Which reflexes can we control more than others? 2. If you could design new reflexes for yourself, what would they be? Vocabulary Afferent: carrying toward a given point Central nervous system: the part of the nervous system in vertebrates that consists of the brain and spinal cord Efferent: carrying away from a given point Interneurons: connecting neurons Patellar tendon reflex: knee-jerk reflex Peripheral nervous system: nerves and nervous tissue outside the central nervous system Receptor: specialized cell or ending on a sensory neuron that a stimulus can excite Synapse: tiny gap between the axon of one neuron and the cell body of another neuron across which messages are transmitted chemically or electrically Overview Sneezing, coughing, and blinking are simple reflexes. But they aren't as simple as they seem. It's true that reflexes have a simple definition. They're involuntary actions or movements that occur in response to a stimulus. And you may not think that much goes on when you yawn, for example. But you might be surprised. Each reflex action can involve countless complex communications and intricate coordination among nerve cells called neurons. These neurons are found in the central nervous system, which includes your brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system, which includes all the nerves that reach your body's extremities. Not all neurons are alike, however. Sensory (or afferent) neurons carry messages to the brain and spinal cord. Motor (or efferent) neurons carry messages away from the brain and spinal cord. They tell muscles to contract or relax and spur glands into action. Interneurons send messages between nerve cells within the brain, spinal cord, and the periphery. These busy characters make up over 99 percent of the more than 10 billion neurons in our nervous system. But why is the brain involved in reflex actions at all? As part of the nervous system, the brain has specialized functions, only some of which control thought or voluntary movement. The brain stem, for example, manages involuntary reflexes such as breathing and keeping our balance. We don't consciously decide to do these things. But a part of our brain is still involved. Reflexes serve as primitive responses that protect our bodies from danger and help us adjust to our surroundings. We cough, for example, when an irritant enters our windpipe and we need to expel it through our mouth. We sneeze when we need to clear our nasal air passages of irritants and allergens. We blink when danger threatens the sensitive tissues of the eye and when we need to moisten and clean the cornea. (This reflex occurs 900 times an hour!) We yawn when nerves in the brain stem find there's too much carbon dioxide in the blood. A yawn makes the muscles in our mouth and throat contract and forces our mouth wide open, allowing us to expel carbon dioxide and take in a large amount of oxygen-rich air. Without these reflex actions, we would be unable to survive. So even though they may be simple, these reflexes are a really big deal. Activity Pit your reflexes against the clock in this reaction-time challenge. How fast do your nerves send and receive messages? Involuntary reflexes are very fast, traveling in milliseconds. The nerve impulses in the neurons that control these reflexes travel an express route. In fact, the fastest impulses reach 520 kilometers (320 miles) per hour! Our conscious muscular response to a stimulus takes a much longer route. See just how fast your brain and nerves respond to stimuli in this experiment. Materials Meter stick (yardstick) Table and chair Chart to record results 1. Sit with your forearm on a table surface so the hand extends over the edge. 2. Have your partner hold the meter stick (yardstick) with the zero end between, but not touching, your thumb and fingers. 3. Ask your partner to release the meter stick without warning. 4. Catch the stick as quickly as you can between your thumb and fingers. 5. Record the centimeter (inch) mark where you caught the stick. 6. Repeat steps 3, 4, and 5 ten times. Have your partner vary the waiting time before each drop. Record the results on a chart. 7. Cross out the highest and lowest numbers on your chart, so only eight numbers are left. Find the mean (average) of these numbers and record it. 8. Repeat this experiment with your partner catching the stick. Record the results. 9. Then switch hands and perform the same experiment. Record these results as well. Is there a difference in reaction time between your writing hand and your other hand? 10. See if an auditory stimulus affects your reaction time. Close your eyes and have your partner say "go" when he or she releases the stick. React as soon as possible. Record your results. 11. Does distraction affect your reaction time? Have your partner ask you simple math questions and repeat the experiment. Again, record your results. 12. Compare your reaction time averages with those of your classmates. Derive a class average. Questions 1. Are there differences in reaction times between rightand left-handed people? Between genders? Between younger and older people? Experiment with test groups. What accounts for any differences? 2. How can you improve your reflex reactions? Test your theories. What can you conclude about the effects of practice and fatigue on reaction time? Adapted in part from A+ Projects in Biology by Janice VanCleave. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (1993). Resources Restak, R.M. (1994) Receptors. New York: Bantam Books. Xenakis, A.P. (1993) Why doesn't my funny bone make me laugh: Sneezes, hiccups, butterflies, and other funny feelings explained. New York: Villard Books. Additional resources 1. Coronet Films: Human body: Nervous system and Human body: Brain. Videotapes. (800) 777-8100. 2. Encyclopedia Britannica Films: The nervous system. Videotape. (800) 621-3900. 3. Queue, Inc.: Experiments in human physiology. Software for Apple II. (800) 232-2224. 4. Queue, Inc.: Nervous and hormonal systems. Software for Apple II, IBM and compatibles, or Macintosh. (800) 232-2224. Additional sources of information 1. American Academy of Neurology 2221 University Ave. SE Suite 335 Minneapolis, MN 55414 (612) 623-8115 2. BrainLink: Explorations in Neuroscience Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX 77030 (800) 798-8244 NEWTON'S APPLE is a production of Twin Cities Public Television and is made possible by a grant from the 3M Foundation. Try This: Extensions Check your knee-jerk reflex. Ask a partner to sit on the edge of a table with legs hanging freely. Use the side of your hand to chop lightly at your partner's leg just below the kneecap (patella) at the patellar tendon. Switch places and repeat the experiment. What could you do to prevent this reflex from happening? Research a disease that affects our reflexes, such as polio or amyotrophiclateral sclerosis (ALS, for short). Read the inspiring stories of people who suffered from these diseases-for example, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Lou Gehrig,and Stephen W. Hawking. Hold a pane of clear plastic or Plexiglas in front of your face, with your nose touching it. Have someone throw a crumpled ball of paper at the plastic, aiming at your eyes. Can you control your blinking reflex? Hold a ruler horizontally just below your eyes, resting it on the cheekbones. Close your eyes for a minute. As you open them, have a friend shine a flashlight directly into your eyes and measure the distance the pupils contract. Test to see if this pupillary reflex works with both eyes or just the eye exposed to the light. Why does this reflex occur?