anmef_kanowna

advertisement

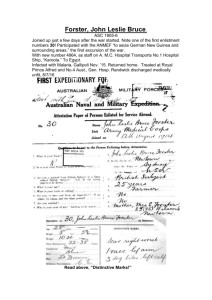

The Northern Miner Wednesday January 25, 1928 EARLY WAR INCIDENTS With the Kanowna to New Guinea What the Official History Says North Queenslanders who were mobilised in the early days of the war, and embarked immediately on the steamer Kanowna, and particularly those who went to New Guinea, will read with interest in the story of New Guinea as told in the official History of Australia in the War, “the reference to the ship”— Australia’s first transport. A mutiny among the crew occurred at Port Moresby and the Kanowna was ordered back to Townsville. That much was known by the troops of the reasons for their return, and no more, and it is not till this late stage that they became acquainted with the ideas which ran through the minds of the high officers in charge of the Pacific operations. War was declared by Great Britain on Tuesday, August 4, 1914, and the same day a proclamation was issued mobilising the Kennedy Regiment, the Australian Garrison Artillery and rifle clubs. Men from Mackay, Bowen, Ravenswood, Charters Towers and Townsville were immediately drafted to Townsville, while the Cairns and district men were required for war service, but where, no one knew, and there was anxiety in homes over a wide area. The Kanowna in her usual peacetime service, arrived at Townsville on Wednesday 5th and was commandeered by the military authorities. Still no one knew of the troops’ destination. A reference the next day by Senator Millen (then Minister for Defence) to the garrisoning of Thursday Island was the only inkling that was ever given of the possible destination. Hurried preparations were made at Kissing Point and at Cairns in the fitting out of troops, but material was not available, and those in charge had to do their best with their limited supplies. Many of the troops had just been drafted into the citizen forces in their eighteenth year, old soldiers had rejoined the regiment, and rifle club members without any previous experiences were also included in the ranks. Thus when the troops marched to the wharves, and embarked on the Kanowna on Saturday 8th, they presented an odd sight. Some had uniforms; some had a mixture of military and civilian clothing, while others were attired in civvies only. But there was no mistaking the spirit of the men. Tear stricken women lined the route to the wharf and saw the transport off, but the spirit of their menfolk must have been re-assuring to them. There were over 1000 troops aboard the Kanowna when she left Cairns (about 800 from Townsville) and as must be realised, the accommodation was totally inadequate for such a large body. Thursday Island was the ship’s destination all right, but a few days after arrival there a call was made for 600 volunteers for six months’ service in the Pacific. More than were necessary offered, but 600 rejoined the ship, and the Kanowna again put out. The vessel proceeded to Port Moresby, and remained there for three weeks until the arrival of the Berrima and her convoy from Sydney. Some of the men were sent ashore and such duties as guarding the wireless station, etc., were undertaken, the others remaining aboard; it all became very irksome, and they hailed the arrival of the ships from the south with delight. They began to move off with them, but were doomed to disappointment and an early return to Australia. Let the historian (Mr S.S. MacKenzie) take up the story as told in the New Guinea section of “Australia in the War.”: —“From Moreton Bay the Berrima steamed along the Queensland coast. Off the low spit of Sandy Cape she was met by the light cruiser Sydney, and the ships proceeded in company to Palm Island, which lies north of Townsville inside the Barrier Reef. The cruiser, Encounter, was already there, when on August 14 the Berrima made the islands. The same rendezvous was appointed for the supply ship, Aorangi, the submarine tenders, Protector and Upolu, and the submarines AE1 and AE2. It had at first been intended that the Berrima should be escorted by the Sydney and Encounter to Port Moresby, where she would be joined by the s.s. Kanowna with a contingent of 500 volunteers from the Kennedy Regiment—the citizen force battalion raised in North Queensland. But Rear Admiral Patey, when he found himself called upon to escort the New Zealand expedition to Samoa, ordered the destroyers from Rossel Island to Port Moresby, and gave particular instructions that the Berrima should not be brought north of Palm Island until he returned from Samoa. This meant that the expeditionary force was “hung up” for an indefinite period. Delay at this stage was peculiarly irksome to those charged with the performance of an urgent mission. It was also extremely trying for the troops, restricted day after day to the same surroundings after the sense of movement, the high spirits and high expectations which filled the first days of the voyage. The men were in no mood for anything except the enterprise on which they had set out. Still, they were far from being idle. From the time the Berrima left Sydney, the naval and military units were drilled and kept employed as thoroughly as the limited space on board would permit. During the stay at Palm Island they were taken ashore nearly every day, across a shingle beach to rocky ground and bush—a terrata ill-suited to manoeuvres, but it taught them how to maintain touch in thickly wooden country, and the person afterwards, proved invaluable in the dense jungles of New Britain. A short rifle range was established, and the men received careful instruction in musketry. The daily landing had also the advantage of giving the naval reservists constant training in boat work and the landing of troops. On August 30, Captain Glossup, of H.M.A.S. Sydney, received wireless instructions from the Rear Admiral that the Sydney, with all companions and convoy was to be at the rendezvous east of the Louislade group by 7 a.m. on September 9th. The Upolu and the submarines should accompany him. If they had joined up, and fuel were available. The Sydney and Encounter were to extemporise minesweeping apparatus, and all ships were to be coaled and oiled either at Port Moresby or at the rendezvous near Rossel Lagoon. Glossup also instructed for the transfer of fifty men from the naval forces required for garrisoning Rabaul, and Herbertshohe, and occupying Angaur, Yap, and Nauru. In accordance with these orders, the Sydney, Encounter, Berrima and Aorangi sailed from Palm Island on September 2 and proceeded to Port Moresby, to complete there with coal and oil, and to collect the other ships of the convoy. Two days later, the Upolu, the Encounter, and the submarines AE1 and AE2 left Townsville for the rendezvous. But a defect in the Upolu’s condensers reduced her to a speed of six knots; she and the Protector were therefore ordered to proceed direct to Rabaul, which even at their best speed, they could not reach till after the arrival of the main expedition. On arrival at Port Moresby, which was reached on 4th September, Colonel Holmes inspected the troops on board the Kanowna. The result was extremely discouraging. The Kennedy Regiment had orders in case of war to reinforce the garrison of Thursday Island, and its eager but inexperienced officers had, as soon as they received news of the outbreak of war, hastily mobilised the regiment, requisitioned the Kanowna (under the provisions of the Defence Act), and were duly transported to that destination. At Thursday Island volunteers had been called for service outside the Commonwealth, and half the regiment (that is 500 men) had responded, the Kanowna being retained to carry them wherever they might be required. In these circumstances a commander with inadequate military training, with no regimental staff, and served by only youthful or comparatively inexperienced company officers had encountered exceptional difficulties. Many of his men were just “trainees,” boys of 18 to 20 years, physically fit for tropical campaigning. Supplies of clothing and boots were non-existent or unsuitable, food supplies were deficient, there were no tents, no mosquito nets, no hammocks, and the shipboard accommodation was hopelessly inadequate, as might be expected in a vessel unexpectedly taken over for was duties. The ship’s company, too, which had not been consulted or asked to volunteer and which was expected to take the vessel far from the limits of its authorised run, was discontented and ready to strike. In view of all these difficulties, Colonel Holmes decided to tell the Admiral that he regretfully considered the Kanowna’s troops unfitted for active service, and to recommend that they be returned to the state to which they belonged. In the meantime the Admiral was informed by wireless from the Sydney that it was considered desirable to discharge the transport Kanowna and the troops abroad her, unless he urgently required them. On the morning of September 7th, the cruisers Sydney and Encounter, the auxiliary cruiser Berrima, the destroyers Warrego and Yarra, the submarines AE1 and AE2, the transport Kanowna, and the supply ship Aorangi left Port Moresby for the appointed rendezvous at Rossel Island. The Parramatta followed convoying the collier Koolonga and the oil tanker Murex, as these vessels were too slow to keep with the others. The reef-guarded entrance to Port Moresby had not been left far behind when it was noticed that the Kanowna was falling back. Shortly afterwards she stopped. The Sydney turned in a half circle, and went back towards her, sending on one of the destroyers, which ranged alongside the drifting transport. It was then ascertained that the firemen had mutinied and refused to stoke the ship, objecting to proceeding any further with the expedition. Though the troops had volunteered for overseas service, the Kanowna’s crew, it must be remembered had not. The Sydney signalled to the Berrima “I have sent the Kanowna direct to Townsville.” Another message ran: “It was only the firemen who mutinied; there were volunteers from the troops to do the stoking. I suggest that trainees be disbanded, and if more troops required, seasoned men who have passed medical test be employed. To this Colonel Holmes replied: “I considered the Kanowna contingent as at present constituted and equipped unfit for immediate service, and in view of to-day’s events, and your action in ordering ship back to Townsville, recommended disbandment, and reorganisation if Admiral considered further troops necessary.” This message was conveyed to the Kanowna, as an official instruction from Colonel Holmes, Admiral Patey, who was informed, agreed that the Berrima troops were sufficient. The disbanding of the Kanowna detachment was a regrettable episode, and caused considerable heartburning; but there can be no doubt, on the facts, that Colonel Holmes was right in his decision that this unit, in the condition in which he found it, was unfit for service with his expedition. The troops on the discharged transport were from first to last the victims of circumstances. They had offered themselves for service, they had been accepted; and they were prepared to do their best. There was no lack of spirit, and their disappointment at being left behind was keen and lasting. If called upon, they would have stoked the Kanowna to New Britain as readily as they did to Townsville. Many afterwards joined the A.I.F. and some of their names will ever be preserved in Australian history. Footnotes: AE1 and AE2 Submarines, were lost early in WWI, AE1 from an unknown cause near Blanche Bay on 14th September 1914, AE2 in the Sea of Marmara on 30th April 1915. On 25th April AE2 was ordered to force the Dardanelles ; this she did, being the first British ship to do so, but in the Sea of Marmara she sustained such damage from enemy gunfire that her crew were compelled to sink her and surrender. Aorangi – (4268) mail steamship on Sydney-Vancouver run from 1897 to 1914, proceeded to England, was taken over by the Admiralty, and was scuttled at Scapa Flow with other vessels to form a barrier against submarine attack. In 1921 she was raised and converted into an Admiralty hulk moored in Scapa Flow. Kanowna – (6983) Steamship, went ashore and sank in 60 fathoms off Cleft Island, west of Wilson’s Promontory, Vic., 17th February, 1929. The 142 passengers and 130crew were taken off by the steamship Mackarra, but the cargo valued at £100,000 ($200,000) was a total loss. The Australian Encyclopaedia – Volume IX p 393. New Guinea. On 7th August 1914 the Federal Government received from London an official message suggesting that the seizure of the German wireless stations at Rabaul, Yap and Nauru would be “a great and urgent imperial service”. Volunteers were called for, and on 19th August Colonel William Holmes (q.v.) left Sydney in the Berrima with about 1500 men—six companies of the naval reserve, a battalion of infantry, two machine-gun sections, and signalling and medical detachments. They were joined by a citizen-force battalion which had volunteered at Townsville, but partly because the stokers of their commandeered transport refused to proceed, this battalion was sent back during the voyage. The rest of the force (known as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force), after 11 days’ training at Palm Island off the Queensland coast, reached Blanche Bay in New Britain on 11th September, escorted by H.M.A.S. Australia and three destroyers. At 6 a.m. on that day two parties of naval reservists (25 men in each) landed at Kabakaul and Herbertshohe (now Kokopo) with orders to discover and capture a wireless station known to exist somewhere inland. The Kabakaul party, after advancing about two miles, came under rifle fire from a small entrenched position across the Bitapaka road; reinforcements were quickly landed from the destroyers and the Berrima, and after a tough fight the attackers bravely charged the enemy and forced him to surrender. The wireless station was captured that evening. Two Australian officers and three seamen were killed, and four seamen wounded, the first Australian casualties in the war. The Herbertshohe party penetrated five miles inland without opposition, and then returned. On 12th September the infantry entered Rabaul without opposition and next day the military occupation of the island was formally proclaimed. The German governor had retired to Toma, about 10 miles inland, but a raid towards his headquarters on the 14th, aided by a few shells from the Encounter, brought him to terms, and on the 17th he signed a capitulation which, though it did not formerly surrender any territory, guaranteed that throughout German New Guinea (a name covering all German colonies in the Pacific except Samoa) no resistance would be offered to British occupation. On the 21 st the enemy troops, German and native, laid down their arms, and on the 24th Friedrich Wilhelmshafen (Madang), the chief settlement on the New Guinea mainland, was occupied without resistance. The occupation of the outlying islands proceeded gradually: Kavieng in New Ireland was taken on 21st October, Nauru, whose wireless station had been destroyed by the Melbourne on 9th September, was occupied on 6th November, the Admiralty Group on 21st November, and Bougainville and Buka on 9th December. Colonel W. Pethebridge (q.v.) sent from Australia with a special force (known as the Tropical Force) for such tasks, took over in January, 1915 from Holmes who, with most of his troops, returned to Australia; they then joined the A.I.F. and were the first troops of the 2nd Division to reach Gallipoli. Pethebridge, with an administration selected of the colony, which until the end of the war was considered to be German territory under temporary military occupation. Anzac Way Memorial Booklet – Townsville April 7th, 2001 Papua New Guinea WWI 1914 On 18 August 1914, men of the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force, raised at the outbreak of war, embarked at Sydney for German New Guinea. They were the first infantry to leave Australia. After 11 days training at Palm Island off the Queensland coast the force reached Blanche Bay in New Britain on 11 September. Landing at Kabakaul at 6 a.m. that day the naval reservists came under fire and, after a tough fight, charged the enemy and forced him to surrender. Two Australians and three seamen were killed and four seamen wounded, the first Australian casualties in the war. Samoa WWI 1914 On the 30th August 1914 the German wireless station was seized when the Commander of the Australian Station asked for a surrender of the wireless station and the Imperial possessions under German control. Although there was no formal surrender, no resistance was offered to the landing of armed forces from New Zealand and Australia and the occupation of Samoa was carried out without casualties. Ocean Island and Nauru WWI 1914 HMAS Melbourne destroyed a German wireless station on Nauru on 9 September 1914. Australian troops occupied the island on 6 November of the same year. Researched and written by Donna Baldey - 2008