46. The Path to Power

advertisement

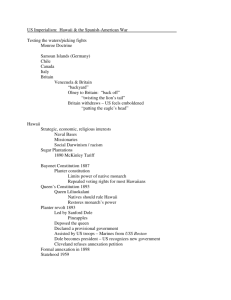

The Path to Power We haven’t studied foreign policy for quite some time. We’ve spanned our continent with a railroad, exponentially increased the economic strength of the country, moved much of the population west, and launched two or three reform movements all without breathing a word about what was happening in the rest of the world. Seeing how the United States of America was about to save the peoples of the Earth from tyranny twice, we should turn our attention to how we could possibly be in a position to do so. Our question is essentially how did the USA become the most powerful nation on Earth? Since we haven’t discussed foreign policy in a while, let’s review. George Washington set the precedent of isolationism with his Neutrality Act and his warning in his Farewell Address to avoid entangling alliances. The War of 1812 was our first positive step toward achieving a position of significance in the world. At any rate, we were no longer a prize in the rivalry between the French and the British. Then isolationism was reiterated by the Monroe Doctrine. Next, Manifest Destiny enflamed our people so our attention became focused on conquering our continent from ocean to ocean. Expansion into this newly acquired territory nearly destroyed us through the slavery debate and subsequent Civil War. We were absorbed in a deep domestic conflict. By the time of the Election of 1896, however, our perspective began to change. The word “imperialism” crept into American rhetoric. Amazingly, there were those who sought to create for the United States the very thing we had rebelled against 120 years earlier, an empire. Imperialism means that a nation controls territory beyond its national boundaries by either asserting military and economic dominance or by actually acquiring the territory as, shudder, colonies. Two main reasons motivated the US to even consider becoming an imperial power. Oddly enough, the first is that farmers and big corporations agreed on one thing—we needed new markets for our grain and manufactured products. The second reason is more predictable. European nations were scrambling in the late 19th century to carve out empires in Asia and Africa. A key imperialistic term defines what these nations sought—spheres of influence. Doesn’t that sound polite? Two whole new continents were opened up as modern transportation methods penetrated the interiors in search of resources. Shouldn’t the United States act before all the spheres of influence were taken? Many Americans, including President Grover Cleveland, said, “No.” As late as 1885, Cleveland was still urging the US to avoid empire when some suggested we should annex the Hawaiian Islands. You have seen Grover Cleveland to be a man of principle who took domestic stands even when they made him unpopular. He kept America loyal to Washington’s position of neutrality. The United States was ill-equipped to take on the race for empire. Can you guess why? We had only a few noteworthy ambassadors in our diplomatic corps because most ambassadors to foreign countries received their positions during the Gilded Age from graft. Remember, being related to someone in the State Department does not necessarily make you competent to reach out to, say, Latvia. You still got a salary, though, even if you never went to Latvia. The most useful Americans in figuring out our role in the world were private citizens who traveled abroad and were sensitive to foreign affairs. In the Victorian Age there was a type of person referred to as “The Thinking Man.” We grew a fair crop of these in the United States, and on business and on vacation many scouted out foreign countries for possibilities. Few foreign countries saw possibilities in the US, however, and many nations neglected to even send us ambassadors. Lord Bryce, though, was an Englishman who saw our potential. In his book published in 1888, The American Commonwealth, Bryce said we were run by “amateur policy makers,” but hinted we would play a larger role in world affairs in the coming century. Our own Senator Albert J. Beveridge was bolder and called for the US to “organize the world to its advantage before it was too late.” Advantages came in many forms. American businessmen saw the opportunity to sell excess goods abroad in order to keep the economy steadily expanding. Most Americans believed democracy was also a commodity we could and should export. The Panic of 1893 encouraged investment in foreign enterprise as a way to turn the economy around, and as our dollars went out the flag followed. There was no more frontier in America, according to Frederick Jackson Turner, who wrote his famous essay the same year the depression began. The solution seemed not “Go west, young man,” but “Go abroad.” Here came yet another book that transformed US history not quite on a par with the Bible or Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but still up near the top. Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, a naval strategist, wrote The Influence of Sea Power upon History in which he urged nationalism backed by naval strength as the key to American success. He said it was the duty of the USA to pursue national greatness just as the great sea powers had of old. The empires of Greece, Spain, and Britain proved that “he who ruled the seas ruled the world.” Many noted Americans were aghast, including William Jennings Bryan. Bryan believed the US should aim merely to be a moral example to the world, not its conqueror. Here we have to begin the formal study of Theodore Roosevelt, a man I have only made passing references to heretofore. Our story finds TR, as he came to be known, Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Roosevelt had written the definitive naval history of the War of 1812 immediately upon graduation from Harvard, and the book is still required to be in the library of any ship in our Navy bigger than a destroyer. He liked ships. He liked them so much he urged the actual Secretary of the Navy to stay home in the summers away from the sweltering heat of Washington, D. C. While the older gentleman was away, TR sent the US Navy on mission after mission around the world testing its capabilities. These missions were not to destroy anything but merely to test how fast US forces could make it to various destinations. Roosevelt also guided bills through Congress calling for the building of new ships all by himself. Welcome to the phenomena of nature known as the personality and confidence of Theodore Roosevelt. We will refer to them continually for quite some time. Roosevelt of course sided with Alfred Thayer Mahan, as did the British and the Germans who also read Mahan’s book. Ominous music in the background, please. Other nationalistic pro-imperialism players included William McKinley’s Secretary of State, John Hay. Hay was not alone. American philosophers, diplomats, lawyers, professors, Social-Gospelites, and real Gospelites (missionaries) all could be classified as imperialists. Philosophers wanted to see how American ideals would improve life. Diplomats and lawyers stood to gain if the US became more engaged with the rest of the world. Professors wanted to study abroad and write books. Various types of Christians launched the huge world-missions impulse of America with various motives. All of these endeavors contributed to America’s desire for and pursuit of spheres of influence. Now that you have a basic introduction to imperialism, events exploded. Germany moved to take over the Samoan Islands way out in the South Pacific. For reasons I’ll explain later, the US had already set our sights on them. TR dispatched our Pacific fleet to race the Germans there, and it arrived just in time to be largely destroyed by a typhoon. Undaunted, Roosevelt seized that opportunity to requisition the construction of newer, better ships. Also, some US sailors got in a brawl with a Chilean mob in Valparaiso. We protested the killing of two and the injuring of 17 of our sailors in this incident and warned retaliation if Chile did not apologize and pay an indemnity, which it did. The United Kingdom and Venezuela then disputed the boundary of Venezuela and British Guiana right in our back door. The British threatened to send a military force which would have violated the Monroe Doctrine. A powerful Navy suddenly seemed like an imperative goal. To make matters much more serious, Cuba sought independence from Spain. Ironically, while contemplating securing colonies for the United States, Roosevelt and others were all for helping Cuba break away from the nearly dead Spanish Empire. TR said publicly that the US would lose self-respect if we didn’t help our neighbors achieve freedom, and privately hoped that war with Spain would finally convince the US to seize Hawaii. The Cuban revolutionary leader, Maceo, was murdered in 1896, and Cubans appealed to the US for help. An air of war became noted in American discourse, and a popular shift moved toward intervention. Other events exploded on the island of Cuba. Spanish General “Butcher” Weyler herded Cuban revolutionaries into “refugee” camps (concentration camps) where thousands died. McKinley desperately wanted to avoid war, but he demanded that Spain change their reconcentracion policy. The Spanish ambassador to the US fired off a letter back home in 1897 in which he referred to McKinley as weak. Tensions mounted when the Depuy de Lome letter was leaked to the press. Speaking of the press, a new term needs to be mentioned. Yellow journalism refers to the practice of certain papers to sensationalize the news in order to boost their circulation. William Randolph Hearst was notorious for this style in his battle with Joseph Pulitzer to become America’s largest newspaper publisher. He dispatched Western artist Frederick Remington to Cuba saying, “You provide the pictures, and I’ll provide the war.” Remington encountered the hectic scene of American citizens being evacuated from Cuba and struck upon an incredible propaganda opportunity. An American woman was searched by Spanish authorities as she fled Cuba. While she was actually patted-down while clothed in a private room by a female Spanish customs agent, Remington portrayed her as having been strip-searched by leering Spanish men. His propaganda cartoon (yes, I will show it to you) stirred a spirit of outrage in the public mind. The final straw was the destruction of the U. S. S. Maine, a battleship stationed in Havana harbor to oversee the evacuation of US citizens. The ship exploded and killed 260 officers and sailors. While Spain argued that it must have succumbed to spontaneous combustion in its hold filled with coal igniting its gunpowder magazine (which had happened in other ships), evidence was discovered that the Maine was the victim of an underwater mine. The yellow journalists seized on the charge of sabotage and printed huge headlines about the outrageous Spanish attack. Still McKinley persisted in avoiding war until public pressure and pressure from Congress became too great. Spain agreed to an armistice with the rebels and an end of the concentration camps but not to Cuban independence. These concessions came too late to avoid war, however. On April 19, 1898 Congress heard William McKinley’s reluctant war message and declared war against Spain. Two amendments were added by the Congress that have impacted our relationship with Cuba to this day. The Teller Amendment assured Cubans that, even though we had lusted after Cuba for about 100 years, we were liberating it for Cubans. The Platt Amendment, though, opened Cuba to “our aid,” especially in the event of economic or political turmoil. Essentially we told Cuba we were going to give them a country but intervene almost as if Cuba was a protectorate if they failed to produce a stable government. Watch for the implications of this later. As you might have guessed, Theodore Roosevelt had positioned our Pacific and Atlantic fleets just in case war broke out with Spain. Therefore, Commodore George Dewey steamed into Manila Bay in the Philippines (a Spanish colony) in a surprise attack just at sunrise and destroyed the rusting Spanish Pacific fleet. Our Atlantic fleet penned up that of the Spanish in Santiago harbor in Cuba and destroyed it, too. For the rest of this short war the battle cries of “Remember the Maine!” and “Dewey? We do!” rang out across Cuban battlefields. General William R. Shafter was in charge of the invasion of Cuba. He landed 18,000 disorganized and undersupplied troops, drowning one of Theodore Roosevelt’s horses in the process. The whole American war effort was a bit of a fiasco, but we won anyway. The biggest difficulty was that the Spanish were using the new smokeless gunpowder so it was hard to determine from where in the wooded hills they were firing. While the US troops were pinned down wondering which way to attack, one officer sat up straight on a horse. His subordinates urged him to get down, to which he replied, “The Spanish bullet has not been made that can kill me.” He was immediately shot in the mouth and killed. Theodore Roosevelt to the rescue (you might have wondered what his horses were doing in Cuba). He had resigned his post as Assistant Secretary of the Navy because he wanted to fight in a war. He and Leonard Wood organized the cavalry regiment known as the Rough Riders and charged them up San Juan Hill, although it was actually Kettle Hill and the cavalrymen didn’t get to ride horses. After successfully displacing the Spanish, Roosevelt was shot in the elbow which, while painful, is a fine place to get shot during a battle if you intend to one day run for President. More US troops died of malaria (4,000) than of battle (300) in this “splendid little war,” as John Hay called it. The whole thing was over in August of 1898. The US needed only four months to strip Spain of the last of her empire; the question now was what to do with it? In all we liberated from Spain Cuba, the Philippine Islands, Puerto Rico, and Guam. As we had promised, we gave Cuba to the Cubans. President McKinley said that he couldn’t correctly place the Philippines on a map within 2,000 miles, but the imperialists wanted them. They also wanted to keep Puerto Rico and Guam. US sugar planters had just overthrown Queen Lililuokalani of Hawaii. In a touch of Manifest Destiny the US reasoned that if we didn’t take all these islands some European power or powers would, so we annexed Hawaii and kept the rest. The main goal for keeping and acquiring Pacific islands was to make coaling stations out of them. Our merchant and naval vessels ran on steam generated by coal. These islands could be stockpiled with coal to enable ships to make the Pacific crossing without having to waste cargo space carrying fuel. The main interest of the US was trade with Asia, and with the addition of Wake and Midway Islands (and the Samoan Islands mentioned earlier), a nice line of coaling stations was produced. The question then became should the Constitution follow the flag? In other words, as we acquired territories, would their inhabitants become full US citizens? Would the territories eventually be states? In a series of rulings known as the Insular Cases, the Supreme Court said, “No.” They said the Constitution did not give the US government the right to govern other peoples (an isolationist interpretation which did not stop us). The Filipinos did not like our intention to keep the Philippines and rebelled against us under Emilio Aguinaldo. He was an insurgent leader we had provisioned to go into the jungles on his home islands and lead a rebellion against the Spanish. Our first taste of jungle warfare did not go well. The Filipino Insurrection lasted until 1901. 4,000 US troops were killed, this time in battle. The Filipinos were a small people but fierce. They wrapped their torsos tightly in banana leaves and could make it to our lines even though shot several times and still kill our soldiers with machetes! The need to knock enemy troops down changed the .38 Special service revolver for American officers to the .45 Colt automatic. Aguinaldo was eventually captured after a grueling conflict much worse than the Spanish-American War. Notable anti-imperialists (or isolationists) included Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain, and Carl Schurz, a German immigrant and social reformer who rose to be a Senator. These men were unable to sway the tide, and some isolationists even appeared racist in their stated hesitancy to bring “anymore dark people” under the control of the United States. Anti-imperialists saw the US as taking on the role of the UK which we had fought against in the American Revolution, and said America was abandoning the Declaration of Independence and moral law. An eerie image symbolic of America’s position on the Philippines was embodied by 350-lb. William Howard Taft’s role as Governor of the islands. He danced once with a diminutive Filipino lady and regularly referred to the Filipinos as “our little brown brothers.” The United States did not allow independence for the Philippines until 1946 after World War II. We retain the other islands still.