First Section (pp 3-14)

advertisement

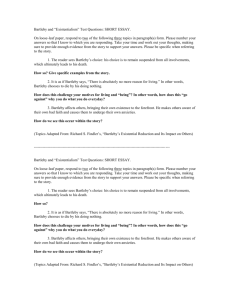

First Section (pp 3-14) Summary The elderly narrator promises to relate what he knows about a peculiar man, one Bartleby, a scrivener (copying clerk) who worked for him some time ago. Before he gets into Bartleby's story, he introduces himself and the other employees of his office. Of himself, he says that he is a man always convinced that the easiest path is best. Though a lawyer, he never goes before juries or judges: he runs a business dealing with rich men's bonds, mortgages, and title deeds. He takes no risks: ""All who know me, consider me an eminently safe man" (4). A short time before the central story begins, the narrator had been appointed Master in Chancery, a position that has since been eliminated. In an aside, the narrator says that he considers the elimination of the post a premature act, particularly since he'd counted on the lifelong security guaranteed by the job. The offices of our story are on Wall Street. On one side, the windows look on the interior of a light shaft. On the other side, the view is of a brick wall. Two copyists and an office boy work for the narrator at the time before Bartleby's arrival. The first copyist is Turkey. Turkey is productive in the mornings, but he's drunk by noon. From that point on, he is less than productive, but the narrator's attempts to send him home early have never met with success. When drunk, he's brash and over-enthusiastic. Nippers, the second copyist, is "the victim of two evil powers ambition and indigestion" (9). Though not a drinker, young Nippers' natural temperament is so irritable that it hardly matters. But because his irritation is caused by indigestion, his irritability wanes as the day goes on. Thus Turkey is productive while Nippers is foul-tempered, and Nippers is productive while Turkey is drunk. Ginger Nut, the office boy, is a lad of twelve whose nickname comes from the ginger nut cakes he fetches for the men. Bartleboy responds to an ad the narrator put in the paper. He is a pale and miserable-looking man: "I can see that figure now pallidly neat, pitiably respectable, incurably forlorn" (11). He also describes Bartleby as "motionless." The narrator hopes Bartleby's quietness will calm the hot tempers of the other two copyists. The office is divided into two rooms, one occupied by Nippers, Turkey, and Ginger Nut, and the other occupied by the narrator. Behind the narrator's desk is a bust of Cicero, the great Roman writer and orator. The narrator installs Bartleby in his own room, putting him at a desk by a window that looks out onto a wall. Bartleby's workstation is separated from the narrator's by a folding screen. Part of a scrivener's job is the tedious work of double-checking a copy's faithfulness to the original. One man reads from the copy, while the other looks at the original. One day, when the narrator calls Bartleby to assist him, Bartleby answers simply, "I would prefer not to" (13). Though the narrator is initially angry, Bartleby's refusal is so listless, so utterly without violence or ill will, that the narrator lets it go. He proofreads with another employee. Second Section (pp. 14-25) Summary A few days later, the narrator needs to proofread four quadruplicates of an important document. He calls in all of his employees to sit and proofread while he reads aloud from the original, and all of them come except for Bartleby. When called on specifically, Bartleby answers as before, "I would prefer not to." When the narrator tries to reason with him, Bartleby simply repeats, "I would prefer not to." The narrator becomes agitated, and is so taken aback by Bartleby's refusals that he looks to his employees for support. Because it is morning, Turkey is calm and measured and Nippers is angry. Ginger Nut replies, smiling, that he thinks Bartleby is not quite right in the head. But the narrator lets it pass, and, as Bartleby won't budge, the men get on with their work. Over the next few days, the narrator observes that Bartleby never leaves his desk. He seems to live entirely on the ginger nut cakes brought to him by the office boy. For some reason, something about Bartleby touches the narrator. He's concerned that if dismissed, Bartleby will be vulnerable to other employers who will be less forgiving of his eccentricities. He resolves to help Bartleby if he can. But sometimes Bartleby's refusals anger him. One afternoon, he loses his temper. When he goes to his employees to ask their opinion, Nippers is mild and Turkey wants to punch Bartleby's lights out (it being afternoon). The narrator calms Turkey down and returns to his office, closing the doors. He makes a series of requests to Bartleby, but the answer is always the same. At one point, he roars Bartleby's name until Bartleby appears from behind his screen: "Like a very ghost, agreeably to the laws of magical invocation, at the third summons, he appeared at the entrance of his hermitage" (19). Although the narrator considers some kind of drastic action, at the end of the day he simply goes home. Days pass. Bartleby's good qualities reconcile him to the narrator: he is constant, almost always industrious if he isn't in one of his reveries, and is always there. He is at the office first in the morning, and is the last to leave. One Sunday, when the narrator is on his way to Trinity Church to hear a famous preacher, he decides to stop in at the office. When he tries to get through the door, he finds resistance from inside. Bartleby is there, in a state of undress, and he says that he would prefer not to admit the narrator. He suggests the narrator go for a walk. When the narrator returns after a short walk, Bartleby is gone. But the narrator finds evidence that Bartleby has been living at the office. He sleeps on a sofa in the corner, and there is a razor and a ratty old towel. This revelation moves the narrator. Wall Street is completely empty when not in business. He searches Bartleby's desk, and finds Bartleby's money wrapped in a little handkerchief. He reflects on Bartleby's situation. Although he feels pity for Bartleby, the man also repulses him. The passage is worth quoting at length: My first emotions had been those of pure melancholy and sincerest pity; but just in proportion as the forlornness of Bartleby grew and grew to my imagination, did that same melancholy merge into fear, that pity into repulsion. So true it is, and so terrible, too, that up to a certain point the thought or sight of misery enlists our best affections; but, in certain special cases, beyond that point it does not. They err who would assert that invariably this is owing to the inherent selfishness of the human heart. It rather proceeds from a certain hopelessness of remedying excessive and organic ill. (pp. 24-25) The narrator doesn't make it to Trinity Church that day. He resolves to ask Bartleby some questions about his past. If Bartleby does not answer, the narrator will dismiss him, although he will try to help him with expenses if Bartleby should wish to return to his place of origin. Third Section (pp. 25-38) Summary The narrator summons Bartleby. When questioned about his past, Bartleby simply replies that he would prefer not to answer. The narrator tries to convince Bartleby to take up some of the normal duties around the office. When he says he would prefer not to, Nippers bursts into the room, furious. The narrator tells Nippers that he would prefer for Nippers to leave. The narrator realizes that of late, he has been using the word "prefer" constantly. Turkey comes in, suggesting that Bartleby take to drinking to improve his moods, so that he can work. Turkey is using the word "prefer" in nearly every sentence, and the narrator worries that Bartleby's presence is somehow contaminating them. But he does not dismiss Bartleby just then. The next day, Bartleby stops copying altogether. The narrator realizes that working by the dim light of the window (which faces a wall) has temporarily damaged Bartleby's eyes. But even though he cannot copy, he refuses to do other work. Some days later, Bartleby announces to the narrator that he has given up copying. Even if his eyes should get better, he will copy nothing. Time passes, and Bartleby is still a fixture around the office. Finally, the narrator dismisses him, giving him six days to go. But the six days pass, and Bartleby is still there. He gives Bartleby some money, telling him firmly but gently that he must go. His speech assumes that Bartleby will leave; he asks Bartleby to lock up on his way out. On his way home that night, the narrator congratulates himself on his handling of the situation. But the next morning, his anxiety increases as he nears work. At the corner of Broadway and Canal Street, he hears men betting money on something, and to his ears it seems the whole city is thinking of Bartleby. When the narrator arrives at the office, at first it seems that Bartleby is gone. But he's there, and he tells the narrator to wait before entering. The narrator goes on a walk, and when he returns, he confronts Bartleby. But Bartleby is both passive and unyielding, as always. At first, the narrator's temper rises, but he remembers a murder that took place in a Wall Street office, when two colleagues lost control of themselves, and he calms himself. Eventually, he reconciles himself to Bartleby's presence. He decides to let Bartleby stay. But professional friends who come to the office find the arrangement bizarre. The narrator worries that his reputation is being damaged by the bizarre man who stays at his office, so he suggests again that Bartleby should leave. Bartleby will not. So the narrator moves his office. On the final moving day, the narrator is slightly choked up as he leaves Bartleby. Fourth Section (pp. 38-46) Summary Some time after the move, the narrator receives a visit from the new tenants of his old offices. They ask him to do something about Bartleby. The narrator protests that he has nothing to do with Bartleby. But a few days later, a large group of people is waiting for the narrator at the door. Among them is the landlord of the old office building. They all insist that the narrator must do something, since he was the last person to have anything to do with Bartleby. The new tenants turned Bartleby out of the office, but now he haunts the building, sleeping in the entry at night. One of them even threatens to complain of this incident to the papers. The narrator agrees to meet with Bartleby. Bartleby is nonchalant and listless as ever. The narrator tries to propose different occupations for Bartleby, but Bartleby says each time that the suggested job would not please him. Finally, in desperation, the narrator offers Bartleby a place to stay in his own home. Bartleby refuses, and the narrator leaves him. Hoping to avoid the anti-Bartleby corps, the narrator stays out of work for a few days. When he returns, he finds a note telling him that Bartleby has been arrested and moved to the Tombs as a vagrant. Bartleby offered no resistance. A whole procession of people went with him through the busy streets of noontime Manhattan. The narrator goes to the Tombs (the name for the Halls of Justice), and asks to see Bartleby. He finds Bartleby in one of the yards, facing a wall. The narrator fears that from the windows murderers and thieves are watching. Bartleby acknowledges him, but the narrator's attempts to cheer him up are fruitless. Bartleby replies calmly, "I know where I am" (43). The narrator bribes a turnkey who dubs himself the grub-man to make sure Bartleby is well fed. When the grub-man offers Bartleby dinner, Bartleby says he would prefer not to eat just then. When the narrator returns several days later, he searches for Bartleby all around the complex. Finally he finds Bartleby dead, huddled at the base of a wall. He learns that Bartleby had stopped eating: he preferred not to. The narrator has a final bit of information to share with us. Some time after Bartleby's death, he heard a strange rumor. Before working as a scrivener, Bartleby had been a clerk at the Dead Letter Office at Washington. He lost the job due to a change in the administration. The narrator is horrified by the idea: for one who was already prone to melancholy, work at the Dead Letter Office would have been a dark and terrible thing. The undelivered letters are burned by the cartload. The narrator imagines letters bringing hopeful news, or forgiveness, or needed money; but all the intended recipients are now gone, the letters thwarted from their purposes. He finishes with the famous ending: "Ah, Bartleby! Ah, humanity!" (46).