Thin-Slice Vision

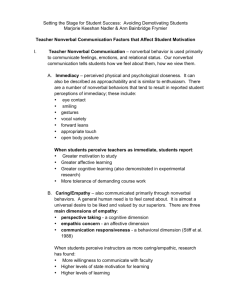

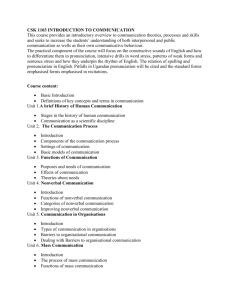

advertisement