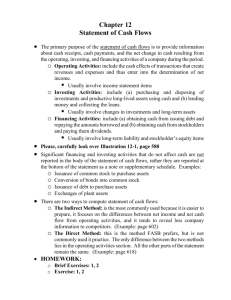

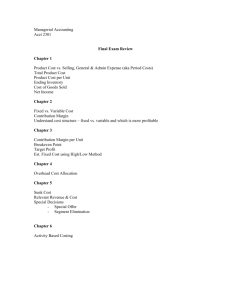

chapter 5 - Amazon Web Services

advertisement