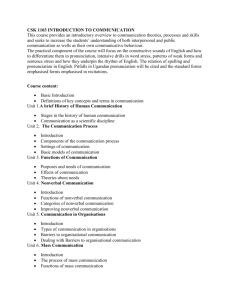

Nonverbal Communication: Kinesics & Proxemics

advertisement

1 INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION Lecture 4 Nonverbal communication [SLIDE 1 – Title] [SLIDE 2 – Key Ideas] Key Ideas Definition of nonverbal communication How much of communication is nonverbal Kinesics Proxemics Factors affecting nonverbal communication Artifactual communication Concepts of time What is nonverbal communication? [SLIDE 3 – Nonverbal communication] Definition of nonverbal communication Nonverbal communication is communication by means other than words. Nonverbal communication is a multi - channelled process that is usually performed spontaneously. It typically involves a subtle set of nonlinguistic behaviours that are often enacted subconsciously. (Lustig & Koestler, 1996, pg.187) Nonverbal behaviour is multifaceted as it includes: our body movements 2 where we choose to stand in relation to someone else whether we choose to touch them our dress the way we speak and even our attitude to time More than anything else, nonverbal communication is influenced by our culture. [SLIDE 4 – Nonverbal messages] How large a part of communication is nonverbal? It is agreed that over half of any message is conveyed nonverbally. However researchers differ on exact percentages. On one hand, Mehrabian believed as much as 93% of all social meaning was conveyed nonverbally. 55% body language, 38 % intonation and 7% words. His work focused particularly on trust and believability e.g. Think of a used car salesman or politician – we are aware that their key objective is to persuade us. By contrast, Birdwhistell suggested that 65% of interpretation of meaning is based on nonverbal elements. What is crucial to remember is that verbal and nonverbal communication systems are inseparably linked thus we are able to learn most about nonverbal communication systems by studying them in relation to the verbal. [SLIDE 5 – Functions] Nonverbal messages function in one of three ways. They can: replace reinforce or contradict verbal messages 3 Problems interpreting meaning arise when nonverbal messages contradict verbal messages. Research suggests that when a receiver senses an inconsistency between verbal and nonverbal messages, in general, the unspoken or nonverbal one carries more weight. Nonverbal messages are the ones we believe We have to be very careful about reading nonverbal signals (especially postures) in isolation because they are part of a package of signals. Alan Pease talks about reading clusters of behaviour e.g. does arms folded show defensive behaviour or are you simply cold? The tone of your voice and facial expression would help us understand the true message. Only when a cluster of behaviours occurs can nonverbal signals be interpreted with any degree of certainty. Look at slide 5 and you will see a range of unusual nonverbal communication clearly serving a particular cultural purpose [SLIDE 6 – Maori haka] Culture Culture has a considerable influence over our nonverbal communication. It cannot be assumed that messages conveyed by nonverbal communication can be transferred to other cultures. Most forms of nonverbal communication are culture specific. They can be interpreted only within the framework of the culture in which they occur. Yet, even within a culture, nonverbal behaviour may be misread. Theorists have developed a language for us to talk about nonverbal communication in an effort to clarify meaning For example, Ray Birdwhistell, introduced the term kinesics to refer to the study of body movements in communication. This will be our first point of study. [SLIDE 7 – Kinesics] 4 Kinesics = The study of body movement, gesture, and posture Body movements is used in a broad sense and refers also to movements of the head. Birdwhistell estimated that there are over 700,000 possible physical signs that can be transmitted via body movement. Body Movements One useful classification of body movement identifies five types: (Ekman & Friesen in DeVito p 165 - 167) 1. Emblems are symbols selected by members of a culture to convey intended meanings. They substitute for words, or directly translate into words e.g. nonverbal signs for ‘OK’, ’peace’, hitchhiking sign. These emblems are learnt in same way that we learn words, through imitation. They are as arbitrary as words in that they are specific to age groups, and cultures. Your culture’s emblems are not necessarily the same as the emblems of other cultures This can cause misunderstanding in intercultural communication because shared meanings for an emblem in one culture may be different from the shared meaning of the same emblem in another culture. For example, the gesture made by joining thumb and forefinger to form a circle signals cheery agreement to most of us but has a less positive meaning in other parts of the world. It means “You’re worth zero” in France and Belgium and “money” in Japan. (Adler & Rodman). [SLIDE 8 – Illustrators] 2. Illustrators accompany and literally illustrate what you are talking about. They make your communication more vivid and help to maintain your listener’s attention. They can also help to clarify and intensify your verbal message or complement the verbal message, making it easier to understand e.g. “The fish was this big” where meaning is shown by how far apart the hands are placed. 5 Most of the time we are only partially aware of the illustrators we use. Illustrators are more natural and more universal that emblems. [SLIDE 9 – Affect displays] 3. Affect Displays (affect = emotion) show feeling. They include facial movements that convey emotional meaning – for example expressions on the face that show anger and fear, happiness and surprise. Facial cues are the single most important source of nonverbal communication. We can consciously control affect displays as actors do when they play a role and they can be used to mislead. Many affect displays may be universally recognised. Paul Ekman and colleagues’ research indicates that, regardless of culture, the primary emotional states are the same. He classes these primary emotional states as: happiness sadness anger fear surprise disgust contempt and interest. However cultural norms often affect both the kind and amount of affect displays shown. [SLIDE 10 – Regulators] 6 4. Regulators are the cues listeners give to encourage a speaker, stop a speaker, check a point or get a turn to speak. These are nonverbal behaviours that monitor, maintain, or control the speaking of another individual. When listening, we are not passive. Nonverbal behaviour may include nodding your head, frowning, and making sounds such as, mm-mm, aha etc. They tell the speaker what you expect or want them to do as they are talking e.g. “keep going”, Regulators are culture specific. Each culture develops its own rules for regulating conversation. These again may easily be misinterpreted. Most people nod their heads to agree and shake their heads to disagree but Bulgarians shake their head to agree. [SLIDE 11 – Adaptors] 5. Adaptors are personal body movements that occur as a reaction to a person’s physical or psychological state They are designed to satisfy some need This need may be physical e.g. we scratch to relieve an itch or push our hair out of our eyes so that we can see better. The need may be psychological, as some people bite their lips when they are anxious while some women play with their hair When performed in private they occur in their entirety e.g. you would scratch your head until the itch is gone. But in public, these adaptors usually occur in abbreviated form. For example, when people are watching us, we might place our fingers on our head and move them around a bit but probably not scratch with the same vigour as when in private. Adaptors also seem to be more frequent under conditions of stress, impatience enthusiasm or nervousness. The face, and particularly the eyes, is the most noticed part of the body and their impact is powerful. 7 Research has shown that smiling waitresses earn larger tips than unsmiling ones, and smiling nuns collect larger donations than ones with glum expressions. (Adler and Rodman) [SLIDE 12 – Proxemics] Proxemics Proxemics (Tubbs & Moss, DeVito & Knapp & Hall) is the study of the use of space and what this communicates. It refers primarily to the distance between people as they interact but can also refer to organisation of space in homes and offices. How we use space can dramatically affect our ability to achieve desired communication goals. This field of study was pioneered by anthropologist Edward Hall. Hall believes space speaks just as loudly as words. However, most spatial interpretation is outside our awareness. We learn the dos and don’ts by observation of others rather than through systematic instruction. It is interesting to note, however, that most people are unable to state the cultural norms that dictate their proxemic behaviour. In Oman, how close is it appropriate to stand to someone you don’t know? How close would you stand to someone you know very well? How close would you stand to someone of the same sex? How close would you stand to someone of the opposite sex? It usually takes an outside observer to identify our unquestioned cultural practices which can be the source of many difficulties in intercultural communication. Spatial Distances Hall developed proxemic zones or distances categorised as: intimate personal social and 8 public. However, his research was based on a small group of friends who were uppermiddle-class professionals, so they are not necessarily able to be generalised and will certainly change in different cultures. [SLIDE 13 –Spatial distances] Intimate Distance Intimate distance = 0 to 45 cm (18 inches or less) This begins with skin contact & ranges to 18 inches. This space is reserved for those we feel emotionally close to. Allowing someone to enter this space is a sign of trust. At this distance not only touch but smell, body temperature & feel of breath can be part of what we experience In the close phase it is used for lovemaking, wrestling, for comforting and protecting. Here, communication is primarily nonverbal. Any subject discussed is usually top secret. The far phase still allows people to touch each other and is often used for discussing confidential matters, with the voice usually kept to a whisper. Eye contact is awkward at this distance so eyes seldom meet. In European culture intimate distance is generally reserved for our partner, child, or best friend. Is this also true in Oman? When forced into intimate distance with strangers in an elevator for example, we use nonverbal cues to establish separateness i.e. we avoid eye contact, fold our arms or have our bag in front of our body etc. Personal Distance This is the distance (45 cm to about 1.2 m or 18 inches to about 4 feet) preferred by most conversation partners in a public setting. Touch is still possible but limited to brief pats for emphasis or reassurance. The finer details of others’ skin, eyes & teeth are visible but we can’t discern body temperature or feel the breath. Hall says that people also have boundaries that mark their personal space. It is as if we walk around in an invisible bubble of personal space that we like to keep between ourselves and other people. 9 Your personal bubble keeps you protected and untouched by others. Invasion by others causes distress. When personal space is invaded, we often feel awkward, become uncomfortable and tense. This area of personal space differs from culture to culture. For Americans it is the distance from 0.5 metres to 1.3 metres (from 1½ to 4 feet). The close phase is a distance reserved for very close relationships. The far phase is a comfortable distance for conversing with friends. People from colder climates typically use large physical distances when they communicate, whereas those from warm-weather climates prefer close distances. The personal space bubbles for northern Europeans are large, and others are expected to keep their distance. The personal space bubbles for Europeans gets smaller and smaller as you travel south towards the Mediterranean. The distance that is regarded as intimate in Germany, Scandinavia and England overlaps with what is regarded as normal conversational distance in France and the Mediterranean countries of Italy, Greece, and Spain. Often northern Europeans think their southern counterparts get “too close for comfort,” whereas the southern Europeans regard their northern neighbours as “too distant and aloof.” Social Distance Social distance ranges from 1.2 to 3.6 metres (4 to 12 feet) More impersonal business is carried out at this distance. Sales people and customers are normally happy with this distance. 5 to 7 feet away says “I’m here to help but I don’t want to be pushy.” This is also the appropriate distance for communicating with people we don’t know very well. The close phase is suitable for conversations at social gatherings. The far phase is suitable for business meetings where eye contact is essential, the voice is generally louder than normal and impersonal information is exchanged. Public Distance This is commonly used by managers or instructors addressing work groups and ranges from 3.6 to 7.5 metres or even more (12 feet to 25 feet or more). A more formal style of language and a louder voice are required. 10 Experienced public speakers exaggerate body movements, gestures, enunciation, and volume while reducing their rate of speech. If you want to test this concept of proxemics, the next time you converse with someone, keep inching toward him or her. See how close you can get before the other person starts backing away. [SLIDE 14 - Factors affecting distance] Factors Affecting Spatial Distances The specific distances you would maintain between yourself and another person depend on a wide variety of factors. (See DeVito) 1. Culture Culture is a huge influencing factor. A study looked at the use of interpersonal distance by Venezuelans (high contact), North Americans (moderate contact), and Japanese (low contact). The researchers found that in speaking their own language, Venezuelans sit closest to each other, North Americans maintain an intermediate distance, and Japanese sit farthest from each other. When they use English rather than their native language, people maintain interpersonal distances closer to North American norms. This indicates that when we speak in a foreign language, we tend to approximate the distance norms of that country. (Tubbs and Moss) We don’t consciously calculate these differences while communicating, however. A sense of what distance is natural is so deeply ingrained in us by our culture that we automatically make spatial adjustments and interpret spatial cues. Most people don’t think about personal distance as something that is culturally patterned. However, the misinterpretation of foreign spatial cues can lead to bad feelings which are projected onto the people from the other culture in a personal way. When a foreigner appears to be aggressive and pushy, or remote and cold, it may mean only that their personal distance is different from yours. (Lustig & Koester, 1999, p 220) 2. Status Research shows that people of equal status maintain a shorter distance between themselves than people of unequal status. 11 A manager is able to stand close to his employees but not the other way round. The greater the status difference, the greater the space. It is OK for the boss to get close to an employee but not OK for a lower status person to get closer to a higher status person. 3. Context Context is determined by: the level of formality purpose of the interaction availability of space. Every situation is individual and specific. In general, the more formal the situation is, the greater the space that is maintained. Talking about personal matters or sharing secrets requires a shorter distance while talking about impersonal matters may be done in a larger space. Generally, the larger the physical space you are in, the smaller the interpersonal space. For example, the space between two people talking will be smaller in the street than the space between two people talking in a house. The larger the space the more you seem to need to close it off to make immediate communication manageable. 4. Gender Research findings show that women choose to stand closer to the person they are interacting with than men do and that people approach women more closely that they approach men. 5. Age Distance also increases with age. Children stand closer together than adults. Interaction distance seems to expand gradually from about six to early adolescence when adult distances are used. This indicates that maintained distance is a learned behaviour. 6. Personality 12 Introverts and highly anxious people maintain greater distances than extroverts and people with high self-concept. 7. Territoriality or the need to protect or defend a particular spatial area. This is a set of behaviours people display to show that they own or have the right to control a particular geographic area e.g. a library space marked by personal possessions. Territoriality is a possessive reaction to an area or to particular objects which relates closely to any discussion of the relationship between space and human behaviour. Through territorial behaviour we signal ownership and status. [SLIDE 15 – Haptics] Touch (Haptics) Touch or haptics refers to moving into another’s space & making body contact It is the most basic form of human communication and one of the most important means of communicating nonverbally. [SLIDE 16 – Haptics (Touch)] Touch is essential for psychological and physical development in children and emotional well-being in adults. Touch is used to convey five major meanings (in DeVito): Touch expresses positive and negative feelings and emotions. Protection, reassurance, love, dislike, disapproval are all conveyed through touch. Hugging, stroking, kissing, hitting, and kicking are all ways in which these messages can be conveyed. Touch can be a sign of playfulness e.g. it can be used to signal that the other’s behaviour shouldn’t be taken seriously. Touch is a means to control the other person. “Move over,” “stay here,” and similar messages are communicated through touch e.g. when we stop a child walking across a road when a car is coming. Touching to control may communicate social dominance. 13 In most Western countries higher status individuals are more likely to touch than be touched, whereas low-status individuals are likely to receive touching behaviours from their superiors. Ritualistic touching centres on greetings and departures. Shaking hands to say hello or goodbye is the clearest example of ritualistic touching. You might also hug, kiss or put an arm around a shoulder. Ritualistic touching varies according to culture e.g. in New Zealand Maori culture on formal occasions a “hongi” or touching noses together is used as a greeting. Task related touching is associated with the performance of some functions e.g. by professionals such as doctors or nurses. [SLIDE 17 – Touch behaviour] Cultural Differences in Touch Behaviour Cultures differ in the overall amount of touching they prefer. High-contact cultures e.g. Middle East, Latin America, and southern Europe touch each other in social conversations much more than people from non-contact cultures such as Asia and northern Europe. In one study, of college students in Japan and in the United States, students from the United States reported being touched twice as much as the Japanese students. In Japan, there is a strong taboo against strangers touching, and the Japanese are therefore especially careful to maintain sufficient distance. (Barnlund 1975 in DeVito). Another research study looked at the number of times couples touched each other in cafes in different cities. a) San Juan, Puerto Rico 180 times per hour b) Paris, France 110 times per hour c) London, England 0 times per hour (in O’Sullivan 1994 p62) Cultures also differ in where people can be touched. In Thailand and Malaysia and amongst Maori and Pacific Islanders for instance, the head should not be touched because it is considered to be sacred. (Lustig & Koester) Artifactual Communication Artifactual communication refers to messages conveyed by objects made by human hands. 14 Colour, clothing, jewellery, and the way we decorate our spaces are all part of artifactual communication. We make enormous assumptions about people based on these and based on clothing in particular. Clothing serves as a cultural display as it communicates your cultural and subcultural affiliations. People make inferences about who you are by the way you dress. Whether accurate or inaccurate, these inferences influence what people think of you and how they react to you e.g. your social class your seriousness your attitudes your concern for convention and your sense of style will all be judged partly from the way you dress. “Clothes we select for ourselves are a better indicator of who we think we are than our faces or our bodies. They can be a mirror of what’s inside or a veneer of camouflage against the world that judges quickly on surfaces or a map to display your aspirations”. (Ehrlich p.137) [SLIDE 18 – Paralanguage] Paralanguage Paralanguage is a term used to refer to all the sounds around the words we use Para - Greek for beside or around. The impact of paralanguage is strong. Research shows that, when asked to determine a speaker’s attitudes, listeners pay more attention to the vocal messages than to the words that are spoken. When vocal factors contradict a verbal message, listeners judge the speaker’s intention from the paralanguage, not from the words themselves. (Adler and Rodman) 15 Paralanguage includes voice qualities such as: 1 Tone of voice e.g. sarcasm. Misunderstanding sarcasm is a very common problem in interpreting vocal cues. This is especially true for children, people with poor listening skills, and people from non English speaking backgrounds. 2 Speech rate (pace) New Zealanders speak quite fast - 130-170 words a minute while the average speaking rate is between 125 and 150 words per minute. Do Omanis speak above or below this average speaking rate per minute? Speech rate is highly stable for individuals and for this reason, a faster rate with shorter comments & more frequent pauses is linked to fear or anger so it is a valuable clue. A slower rate of speech is linked to grief and depression i.e. because you are used to the normal rate of your friend’s speech, you pick up on the difference from normal. If you speak too slowly, you’ll be seen as boring, tired or incompetent. Research on rate of speech shows that people who talk fast are more persuasive and are evaluated more highly that those who talk at or below normal speeds. (MacLachlan 1979 in DeVito) In one experiment (DeVito) subjects listened to taped messages and then indicated their level of agreement with the message and their opinion of the speaker’s intelligence and objectivity (MacLachlan 1979). Experimenters used speaking rates of 111, 140 (the average speaking rate) and 191 words per minute. Subjects agreed most with the fastest speech and least with the slowest speech. They rated the fastest speaker as the most intelligent and objective. They rated the slowest speaker as the least intelligent and objective. 3 Fluency The fluency of our speech is closely related to rate but can be a function of intelligence and confidence i.e. the more knowledgeable we are about a subject, the more likely we are to be able to speak fluently on that subject. 16 4 Volume Volume can reinforce or enhance a person’s power base and convey a sense of confidence. Appropriate sound level varies considerably from one culture to another. According to Hall, “An American voice is softer than Arab, Spanish and Indian voices, and a Russian voice is louder than English upper class, Southeast Asian and Japanese” (p121) 5 Pitch Pitch is the frequency level (high or low) of the voice. Pitch is an important element in people’s judgements about a speaker. Vocal cues are sometimes the basis for our inferences about personality traits. If people increase their loudness, pitch & rate of speech, we perceive them as more dynamic& active. On the other hand, we use a low pitch to project authority and confidentiality. A lower pitch is interpreted as authoritative and influential. It is hard to think of any successful professional persuaders with high-pitched voices. George Bush Senior nearly destroyed his 1988 presidential campaign by speaking at a high, strained pitch. Until he had vocal training he was labelled a “wimp”. Margaret Thatcher took voice lessons to lower her pitch in an effort to sound more authoritative. Broadcasters are trained to complete sentences with a slight downward inflection. In general, downward inflections communicate confidence, authority and certainty while upward inflections suggest doubt and uncertainty. Paralanguage also includes vocalisations or noises without linguistic structure such as crying, whispering, moaning, belching, yawning and yelling. So a whole range of nonverbal clues is intimately associated with perception too. [SLIDE 19 – Silence] 17 Effect of Silence “Silence communicates just as intensely as anything you verbalise” (Jaworski 1993 in DeVito) Like words and gestures, silence too, serves important communication functions. Silence allows the speaker time to think as well as time to formulate and organise their verbal communication. Some people use silence as a weapon to hurt others. After a conflict, for example, one or both individuals might remain silent as a kind of punishment. Silence used to hurt others may also take the form of refusing to acknowledge the presence of another person. Silence can be used to communicate emotional responses. Sometimes silence communicates a determination to be uncooperative or defiant. By refusing to engage in verbal communication, you defy the authority or the legitimacy of the other person’s position. The communicative functions of silence are not universal. Americans and Europeans, for example, often interpret silence negatively. Perhaps the silent member wasn’t listening, has nothing interesting to add, doesn’t understand the issues, or is too self-absorbed to focus on the messages of others. Other cultures view silence more positively. Respectful silence in front of elders and teachers is common in Pacific Island cultures. Also silence is sometimes used to avoid being seen to disagree with someone of higher status. How is silence used in Oman? [SLIDE 20 – Time] Time (Chronemics) Study of temporal communication (chronemics) focuses on the use of time, how you organise it, how you react to it, and the messages it communicates. Different cultures make different assumptions about how time should be used or experienced. How time is used is a widely held and consistently imposed view of the proper or appropriate way to conduct oneself as a competent member of the culture. (Lustig & Koester) 18 Concepts of Time Different theorists have devised different ways of categorising time Hall distinguishes between monochronic and polychronic conceptions of time. Monochronic concept of time: Things should be done one at a time Time is segmented into precise, small units Time is viewed as a commodity; it is scheduled, managed, and arranged People are very time driven Making appointments and meeting deadlines is highly valued An event is regarded as separate and distinct from all others and should receive the exclusive focus of attention it deserves. Examples of monochronic cultures include the USA, Germany, Scandinavia and Switzerland. Polychronic concept of time: Many things go on at once Relationships are far more important than schedules There is no great surprise or concern when delays or interruptions occur Appointments will be quickly broken, schedules readily set aside, deadlines not met when friends or family members require attention Multiple appointments are often scheduled simultaneously Examples of polychronic cultures include Latin America, Mediterranean people and Arabs. In one study, researchers examined the accuracy of the clocks in six different cultures and found considerable variation. (Levine & Bartlett 1984). Clocks in Japan were the most accurate, while clocks in Indonesia were the least accurate. Clocks in the USA, Taiwan, England, and Italy, fell between the two extremes (in that order). 19 Not surprisingly, when the speed of pedestrians in these cultures was measured, the researchers found that the Japanese walked the fastest and the Indonesians the slowest. Such differences reflect the various ways in which cultures treat time and their general attitude towards the importance of time in their everyday lives. Psychological time - importance placed on the past, present, or future. Some cultures are predominantly past-orientated, others present-orientated and others have a future-orientation. Every child learns a time perspective appropriate to the values and needs of their society. (Gonsalez & Zimbardo in DeVito & Hecht) 1 Past–oriented cultures Previous experiences and events are most important Primary emphasis is placed on tradition, and the wisdom passed down from older generations Deference and respect is shown for parents and other elders, who are the links to these past sources of knowledge Events are circular, as important patterns perpetually recur in the present, so that the wisdom of yesterday is applicable also to today. 2 Present-oriented cultures Current experiences are most important A major emphasis is placed on spontaneity and immediacy and on experiencing each moment as fully as possible People don’t participate in particular events or experiences because of some potential future gain. They participate because of the immediate pleasure the activity provides Present-oriented cultures typically believe that unseen and unknown outside forces, such as fate or luck, control their lives. Cultures such as those in the Philippines and many Central and South American countries are usually present-oriented. They have found ways to encourage a rich appreciation for the simple pleasures that arise in daily activities 20 3 Future-oriented cultures These cultures believe that tomorrow, or some other moment in the future, is most important Current activities are not accomplished and appreciated for their own sake but for the potential future benefits that might be obtained. Examples of such behaviour include saving today, working hard at university and denying yourself certain enjoyments and luxuries all because you are preparing for the future People from future-oriented cultures believe that their fate is at least partially in their own hands and that they can control the consequences of their actions. [SLIDE 21 – Reading for tutorials] Reading for tutorials Read DeVito, chapter 8, pg 162 – 192 Summary In this lecture we have looked at: Defining nonverbal communication Understanding how often it is used and what happens when verbal and nonverbal messages disagree Defining the elements of kinesics or body movements especially: o Emblems o Illustrators o Affect Displays o Regulators o Adaptors Understanding proxemics or how distance is used in intimate, personal, social and public settings The factors influencing spatial distances. 21 o Culture o Status o Context o Gender o Age o Personality o Territoriality Haptics or touch and the factors affecting it. Artifactual communication and the conclusions others make about us based on how we dress or the artifacts we use Paralanguage and the 5 factors associated with it 1 Tone of voice e.g. sarcasm. 2 Speech rate (pace) 3 Fluency 4 Volume 5 Pitch The ways in which different cultures use silence and finally The ways in which different cultures use time including monochronic and polychronic time and the difference between past-, present- and futureorientated cultures. Conclusion Our nonverbal communication indicates to other people what we might be feeling but it is very easy to be wrong in our interpretations of nonverbal communication. It must be seen as a series of signals and we need to read this package of signals as a whole. Most forms of nonverbal communication are culture specific. They can be interpreted only within the framework of the culture in which they occur. 22 Cultures have an extremely powerful and complex influence on every aspect of our perceptions and behaviour. We cannot assume that our way is the right way. References: DeVito, J. (2007). The interpersonal communication book. International edition (11th edition). USA: Pearson. DeVito, J. & Hecht, M. L., eds. (1990). The Nonverbal Communication Reader. Prospect Heights IL : Waveland Press DeVito, J., O’Rourke, S. & O’Neill, L. (2000). Human communication: the New Zealand edition. New Zealand: Pearson Knapp, M. & Hall, J. (1992). Nonverbal behaviour in Human interaction, 3rd ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. LeVine, R. & Bartlett, K. (1984). Pace of life, Punctuality and Coronary Heart Disease in Six Countries. Journal of Cross Cultural Psychology, 15:233-255 Lustig, M. W. & Koestler, J. (1996). Intercultural competence: Interpersonal Communication across Cultures, 2nd ed. New York: HarperCollins Mehrabian, A. (1978). How we Communicate feelings nonverbally (a Psychology Today Cassette). New York: Ziff-Davis.