church property issues - Canadian Canon Law Society

advertisement

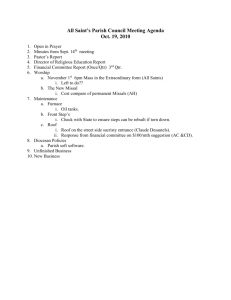

CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON CHURCH PROPERTY ISSUES: CONTEMPORARY CANONICAL CHALLENGES Msgr John Renken, P.H. Introduction I begin by expressing my particular and deep grateful to the leadership of our Canadian Canon Law Society for the kind invitation to offer these reflections on "Church Property Issues: Contemporary Canonical Challenges." The importance of this topic is evident in the media, which these days reminds us of the need to provide proper oversight of Church property, particularly as it conveys tales of misuse of the same at every level of the Church's life, from small parishes to the Vatican itself. All of us are very aware that the process of revising Book VI: Sanctions in the Church is underway, and some may suggest that a revision of Book V: The Temporal Goods of the Church is also in order. Certainly, many can propose various modifications which would perfect the canons of the Code on temporal goods. For the sake of canonical stability, however, it may be best simply to modify a few canons in Book V. Indeed, I would strongly recommend (and hope) that, before there is any revision of the canons in Book V, the provisions of the existing canons be implemented and experienced for some significant number of years. Generally speaking, I would conclude that the greatest "challenges" with Book V are primarily the non-compliance with, and the nonimplementation of, its canons (not primarily the formulation of canons themselves). My reflections today intend to identify a number of issues related to temporal goods which may still need compliance or implementation. Indeed, very respectfully I would propose that the six topics on which I offer some simple reflections present serious challenges if they are not addressed properly, according to the discipline of Church law. Certainly, we could focus on numerous issues involving temporal goods at various levels of ecclesiastical structure. Given the necessary limits of time, today I will focus largely, though by no means exclusively, on canonical challenges involving the safe retention of parish property. As we all know, parishes are the most numerous public juridic persons in the Church, and in every diocese. Much of what is considered pertains also to the ecclesiastical goods of dioceses and other public juridic persons, mutatis mutandis. Six topics will be considered: 1. To Protect Parish Property in the Civil Legal System 2. To Designate Stable Patrimony Legitimately 3. To Identify Acts of Extraordinary Administration 4. To Promote the Effective Involvement of the Parish Finance Council - 85 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON 5. To Provide Diocesan Assistance: Particular Law, Special Instructions, and Other Practical Diocesan Assistance 6. To Apply Penal Law on Financial Malfeasance 1 - To Protect Parish Property in the Civil Legal System Canon 1284 provides a non-taxative listing of responsibilities of administrators of public juridic persons; these responsibilities are acts of administration (indeed, most are acts of ordinary administration).1 The first three responsibilities require administrators, in order to protect the property of the public juridic person, to observe civil laws and to conform to civil legal structures for the sure retention of ecclesiastical goods. Administrators are to "exercise vigilance so that the goods entrusted to their care are in no way lost or damaged" (c. 1284, §2, 1). They are to "take care that the ownership of ecclesiastical goods is protected by civilly valid methods" (c. 1284, §1, 2). Further, they are to "observe the prescripts of both canon and civil law ... and especially be on guard so that no damage comes to the Church from the non-observance of civil laws" (c. 1284, §2, 3). The Code is quite clear in identifying the parish as a public juridic person (c. 515, §3) which is a part of the diocese (which is also a public juridic person: c. 373) but distinct from it (c. 374, §1). Indeed, in the circular letter of the Congregation for the Clergy, issued 30 April 2013, Mauro Cardinal Piacenza, prefect, writes: ...when treating the modification of parishes and the relegation or closure of churches, there is a need of much greater clarity in distinguishing the juridic person of a diocese from the juridic person of a parish. Nowhere is this more important than in questions concerning the ownership of churches, and who is responsible for their upkeep.2 The ecclesiastical goods of the parish are owned by the public juridic person which is the parish, not by the diocese. Indeed, CCEO canon 1020 insists that ecclesiastical goods be recognized in the civil realm as owned by the proper juridic person: Canon 1020, §1. Each authority is bound by the grave obligation to take care that temporal goods acquired by the Church are registered in the name of the juridic person to whom they belong, after having observed all the prescripts of civil law which protect the rights of the Church. 1 This author concludes that only canon 1284, §2, 6 concerns an act of extraordinary administration, as will be discussed below in this study. 2 CONGREGATION FOR THE CLERGY, circular letter presenting "Procedural Guidelines for the Modification of Parishes, the Closure or Relegation of Churches to Profane but not Sordid Use, and the Alienation of the Same" (30 April 2013), prot.no. 20131348. - 86 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON §2. However, if civil law does not allow temporal goods to be registered in the name of a juridic person, each authority is to take care that, after having heard experts in civil law and the competent council, the rights of the Church remain unharmed by using methods valid in civil law. ... §4. The immediately higher authority is bound to urge the observance of these prescripts.3 The parish is a public juridic person erected by the prescript of law (a iure: c. 114, §1); it is a non-collegial aggregate of persons (c. 115, §§1-2) which "all things considered, possess[es] the means which are foreseen to be sufficient to achieve [its] designated purpose" (c. 114, §3). Its legal representative (c. 532) and its administrator (c. 1279, §1) is its parochus (see c. 118). It is perpetual by nature (c. 120, §1); nonetheless, according to the norms of the law, it is subject to merger (c. 121), division (c. 122), and extinction (cc. 120, §1, 123). It is appropriate that any civilly valid structure for the protection of parish property correspond as exactly as possible to the canonical structure of a parish. This means that, in civil law, the parish must be identified as an entity distinct from the diocese,4 of which it is part, and the parochus must be identified as its legal representative and administrator. Inasmuch as the civil structure of a parish will correspond to the ecclesiastical structure, the civil legal structure will require the parochus to receive the consent of the diocesan bishop before he is able to perform, in a civilly validly way, certain actions on behalf the parish (such restrictions would reflect similar restrictions identified in the Code).5 In a given setting, the precise civil structure of the parish will likely depend upon the choice of the competent ecclesiastical authority which it makes in light of options available.6 3 This canon corresponds to CIC canon 1284, §2, 2 but is very much more detailed. 4 John P. BEAL warns: "Unless the proper autonomy of parishes and other juridic persons from the diocese is adequately maintained, secular courts will be inclined to 'pierce the corporate veil' and view parish property as available for settlements of claims against the diocese and vice versa." "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes", in The Jurist, 72 (2012), p. 123. 5 See Francis G. MORRISEY, "Basic Concepts and Principles", in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, p. 14. Morrisey proposes several actions which can identified in civil legal documents as powers "reserved" to the diocesan bishop in order for the parochus to perform them validly. 6 See William W. BASSETT, "The American Civil Corporation, the 'Incorporation Movement', and the Canon Law of the Catholic Church", in The Journal of College and University Law, 25 (Spring, 1999); Mark E. CHOPKO, "An Overview of the Parish and the Civil Law", in The Jurist, 67 (2007), pp. 194-226; idem, "Principal Civil Law Structures: A Review", in The Jurist, 69 (2009), pp. 237-260; idem, "Control of and Administration for Separately-Incorporated Works of the Diocesan Church: A Constitutional, Statutory, and Judicial Evaluation of the Experiences of U.S. Dioceses", in Public Ecclesiastical Juridic Persons and their Civilly Incorporated Apostolates (e.g., Universities, Healthcare Institutions, Social Service Agencies) in the Catholic Church in the U.S.A.: Canonical-Civil Aspects: Acts of the Colloquium, Rome, Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas in Urbe, 1998, pp. 65-95; Patrick J. DIGNAN, A History of the Legal Incorporation of Catholic Church Property in the United States (17841932), New York, P. J. Kennedy, 1935; Jerald A. DOYLE, Civil Incorporation of Ecclesiastical - 87 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON Indeed, it would be most preferred for the Catholic Church to urge legislators to introduce into civil law the structure of a "juridic person" which closely corresponds to that of canon law.7 Once that civil structure is selected, it may be very prudent and helpful to issue corresponding civil statutes and ecclesiastical statutes for the parish. The same corresponding governing norms will then exist, in writing, for both the secular realm and the ecclesial realm.8 It is obvious that merging the property of all parishes of a diocese into a single diocesan-wide corporate sole violates the letter and the spirit of the canons, which establish the diocese and the parish as distinct (though related) public juridic persons. Such diocesan-wide merging subjects the property of all parishes to tort claims against the diocese or against any parish in the diocese. More than once, superior ecclesiastical authority has indicated to diocesan bishops the inappropriateness of the diocesan-wide corporation sole as the civil structure to hold parish property.9 2 - To Designate Stable Patrimony Legitimately 2.1 - The Concept of "Stable Patrimony" The 1983 Code introduces into canon law a new technical term: "stable patrimony" (cc. 1285, 1291; see c. 1295). Stable patrimony can be defined as Athose immovable and movable goods which, by legitimate designation of competent authority through an act of Institutions: A Canonical Perspective (JCD dissertation), Ottawa, Saint Paul University, 1989. John FOSTER, "Canonical Issues Relating to Civil Restructuring of Dioceses and Parishes," in The Jurist, 69 (2009), pp. 311-339; idem, "To Protect by Civilly Valid Means: Reorganization and the Canonical-Civil Restructuring of Dioceses and Parishes," in CLSA Proceedings, 70 (2008), pp. 102-127; Joseph FOX, "Introductory Thoughts about Public Juridic Persons and Their Civilly Incorporated Apostolates," in Public Ecclesiastical Juridic Persons and their Civilly Incorporated Apostolates (e.g., Universities, Healthcare Institutions, Social Service Agencies) in the Catholic Church in the U.S.A.: Canonical-Civil Aspects: Acts of the Colloquium, Rome, Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas in Urbe, 1998, pp. 231-258; Robert L. KEALY, "Methods of Diocesan Incorporation," in CLSA Proceedings, 48 (1986), pp. 163-177; William J. KING, "The Corporation Sole and Subsidiarity," in CLSA Proceedings, 63 (2003), pp. 107-134; Francis G. MORRISEY, "The Expression of Church Law in Canonical and Civil Documents," in Catholic Health Association, The Search for Identity: Canonical Sponsorship of Catholic Healthcare, Saint Louis, Catholic Health Association, 1993, pp. 49-58; Christine Taylor, Canon 1284, §2, 2˚ and the Corporation Sole (JCL thesis), Washington, The Catholic University of America, 2006. 7 See Phillip J. BROWN, "Square Pegs in Round Holes: Toward a Better Model of Parish Civil Law Structures", in The Jurist, 69 (2009), pp. 261-310; see esp. p. 309. 8 See John P. BEAL, "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes", p. 119; John A. RENKEN, "The Statutes of a Parish", in Studia canonica, 44 (2010), pp. 99-148. 9 See SACRED CONGREGATION FOR THE COUNCIL, private letter to ordinaries of the United States (19 July 1911), in CLD, vol. 2, pp. 443-445; APOSTOLIC NUNCIATURE IN CANADA, letter to the bishops of Ontario, prot. N. 6088/05 (14 December 2005). These are reported in John A. RENKEN, Church Property: A Commentary on Canon Law Governing Temporal Goods in the United States and Canada, Staten Island, Alba House, 2009, pp. 48-51. - 88 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON ordinary administration, form the secure basis of a juridic person so that it can perform its works."10 The Church has an innate right to "retain" such goods (c. 1254, §2). The term "stable patrimony" replaces a phrase found in CIC/17 canon 1530, §1 (the predecessor of canon 1292), which identified the requirements for alienation of "immovable ecclesiastical goods and movable ecclesiastical goods which can be saved by preserving them" (res ecclesiasticas immobiles et mobiles, quae servando servari possunt).11 From this, we see that stable patrimony can be comprised of both immovable goods and those immovable goods which can be retained (some immovable goods cannot be retained: e.g., fungible movable goods, which are consumed in their very use). Arguably, the distinction between stable patrimony and non-stable patrimony is the fundamental distinction between all ecclesiastical goods in the ius vigens. In other words, all ecclesiastical goods are either stable patrimony or they are not. The distinction is foundational for the way the Church regards its property. Ecclesiastical goods which are stable patrimony are legally protected against the irresponsible acts of the administrator of the public juridic person which owns them. Special consent from competent authorities, sometimes including the Apostolic See, is necessary before the administrator can enter validly into some contacts involving alienation of stable property (c. 1291) and into some contracts involving a threat to the patrimonial condition of a public juridic person (c. 1295). Although among the purposes for which juridic persons exist is performing acts of charity, especially toward the needy (see c. 1254, §2), donations from stable patrimony can never be given for these charitable acts (c. 1285). Further, as is evident in the discipline of the Eastern Code, stable patrimony should be clearly indicated on regularly updated inventories of ecclesiastical goods made by administrators of juridic persons (see CCEO, c. 1026; see c. 1283, 2-3). Finally, as a clear reading of canon 1263 demonstrates, stable patrimony is never the subject of the diocesan taxation,12 whether ordinary or extraordinary: rather, the tax is based only upon the income of a public juridic person, not its stable ecclesiastical goods. 10 For further reflections on stable patrimony, see Deigo ZALBIDEA GONZÁLEZ, "Antecedentes del patrimonio estable (c. 1291 del CIC de 1983)," in Ius canonicum, 47 (2007), pp. 141-175; idem,, El control de las enajenaciones de bienes eclesiásticos: El patrimonio estable, Pamplona, Ediciones Universidad de Navarra, 2008; idem, "La digna sustentación de los clérigos", in Ius canonicum, 51 (2011), pp. 653-699; idem, "El patrimonio estable en el CIC de 1983", in Ius canonicum, 47 (2008), pp. 553-589; John A. RENKEN, "The Stable Patrimony of Public Juridic Persons", in The Jurist 70 (2010), pp.131-162. 11 The Latin phrase is admittedly difficult to translate. The author is indebted to Dr. Pierre Bellemare, professor of Latin at Saint Paul University, Ottawa, for assistance. Obviously, the phrase "quae servando servari possunt" is a reference only to the res mobiles. This is consistent with authors, including: F. WERNZ and P. VIDAL, Ius canonicum, vol. 4: De rebus, Rome, Gregorian University, 1935, pp. 225-226; S. SIPOS, Enchiridion iuris canonici, Rome, Herder, 1954, pp. 697-698; Stanislaus WOYWOOD and Callistus SMITH, A Practical Commentary on the Code of Canon Law, vol. 2, New York, Joseph F. Wagner, 1948, pp. 207-208. 12 Moreover, Mass offerings are not subject to diocesan taxation (see CCEO, c. 1012, §1). - 89 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON 2.2 - The Legitimate Designation of Stable Patrimony An ecclesiastical good becomes part of stable patrimony only when it has been legitimately designated as such (see c. 1291). Legitimate designation does not happen accidentally. Normally, this designation is an act of administration which is performed by the administrator of the public juridic person.13 When the administrator designates an ecclesiastical good as an asset belonging to stable patrimony, the administrator is performing an act of administration (not acquisition, not alienation) an act of ordinary administration.14 It is a most certain means for the administrator to assure the "retention" 13 Stable patrimony is "normally" designated by the administrator of the public juridic person, but sometimes it is designated in another way. Such other means of legitimate designation include: (1) the legitimate designation by the competent authority which establishes the public juridic person; or (2) the implicit legitimate designation of stable patrimony reflecting usage. Regarding the latter, although continued treatment of an ecclesiastical good as stable patrimony evidences its implicit legitimate designation as such, disputes can arise. In practice, it is most wise to avoid the implicit designation of stable patrimony through usage; instead, stable patrimony should be expressly designated as such by its administrator, through an act of ordinary administration. Regarding goods that implicitly form part of the stable patrimony of a juridic person, see Daniela LEGGIO, "Legislazione canonica e prassi del dicastero per le alienazioni dei beni degli istituti di vita consacrata e delle società di vita apostolica", in Sequela Christi, 39 (2012), pp. 196-197. See also: CONFERENZA EPISCOPALE ITALIANA, Istruzione in materia amministrativa 2005, n. 53 61-62. Available at: http://www.olir.it/areetematiche/86/documents/CEI_Istruzione_materia_amministrativa_2005.pdf The CEI instruction says that every juridic person should make a list of its stable patrimony 14 In my earlier study entitled, "The Stable Patrimony of Public Juridic Persons", (see fn. 10), I had held that the legitimate designation of stable patrimony is an act of extraordinary administration. Now, after more extensive research, I conclude that it is an act of ordinary administration in an article yet to be published in Studia canonica and entitled, "The Legitimate Designation of Stable Patrimony." If the legitimate designation of stable patrimony were an act of extraordinary administration, the administrator of the public juridic person would need the prior written faculty of the ordinary before making the designation (see c. 1281, §3). Such a requirement is excessive and cumbersome, especially since the legitimate designation of stable patrimony is not a rare act of administration. Instead, the legitimate designation is a routine means to Aretain@ ecclesiastical goods (see c. 1254, §1). Many canonists contend that the legitimate designation of stable patrimony is an act of extraordinary administration: e.g., see: Nicholas P. CAFARDI, "Alienation of Church Property", in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, p. 251, see p. 249; Francesco GRAZIAN, "Patrimonio stabile: istituto dimenticato?" in Quaderni di diritto ecclesiale, 16 (2003), p. 288; MARIANO LÓPEZ ALARCÓN, Commentary on Canon 1291, in Ernest CAPARROS, Michel THÉRIAULT, and Jean THORN (eds.), Code of Canon Law Annotated, 2nd ed., Ernest CAPARROS and Hélène AUBÉ (eds.), Montreal, Wilson and Lafleur, 2004, pp. 997-998; Joaquín MANTECÓN, Commentary on Canon 1291, in ÁNGEL MARZOA, JORGE MIRAS and RAFAEL RODRÍGUESOCAÑA (eds.), Exegetical Commentary on the Code of Canon Law, ERNEST CAPARROS (Eng. ed.), 5 vols., Chicago, Midwest Theological Forum, 2004, vol. 4/1, p. 131; Jean-Claud PÉRISSET, Les biens temporels de l'Église, Paris, Éditions Tardy, 1996, p. 200; Alberto PERLASCA, Commentary on Canon 1291, in REDAZIONE DI QUADERNI DI DIRITTO ECCLESIALE, Codice di diritto canonico commentato, 3rd ed., Milan, Ancora, 2009, p. 1025; Stefano RIDELLA, La valida alienazione dei beni ecclesiastici: Prospettive di diritto canonico e civile, Estratto della dissertazione dottorate, Rome, Università pontificia salesiana, 2001, p. 36; ; idem, La valida alienazione dei beni ecclesiastici: Uno studio a partie dai cann. 1291-1294 CIC, Rome, LAS, 2010, p. 117; Diego ZALBIDEA, "El patrimonio estable en el CIC de 1983," in Ius canonicum, 47 (2007), pp. 586-587; idem, El control de las enajenaciones de bienes eclesiásticos. El patrimonio estable, Pamplona, EUNSA, 2008, pp.116-119. - 90 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON of ecclesiastical goods by the public juridic person. Applying all this to a parish: the competent authority to designate legitimately the stable patrimony of the parish is its parochus (and canonical equivalents), not the diocesan bishop or another diocesan official.15 The diocesan bishop may find it especially helpful to issue particular law identifying the kinds of ecclesiastical goods which must be designated legitimately as stable patrimony of the parish, and the ordinary may issue special instructions (c. 1276, §2) explaining how such legitimate designation is to be done. Indeed, the failure to designate legitimately stable patrimony is a violation of penal canon 1389, §1 (the abuse of office) or penal canon 1389, §2 (culpable negligence bringing harm to the public juridic person).16 The 1983 code introduces a new distinction identifying ecclesiastical goods: all ecclesiastical goods are either stable patrimony or non-stable patrimony. This distinction is the basis for determinations in several matters concerning the care of Church property. If the explicit designation of stable patrimony has not yet been made through a legitimate act by the competent authorities, such a designation should be done as promptly as possible. 3 - To Identify Acts of Extraordinary Administration 3.1 - The Meaning of "Acts of Extraordinary Administration" Canon 1254, §1 identifies four aspects of the Church's ownership rights concerning temporal goods: the Church has an Ainnate right@ to acquire, to retain, to administer, and Other canonists, however, do not insist that the legitimate designation of stable patrimony is an act of extraordinary administration: e.g., see: Robert T. KENNEDY, Commentary on Canon 1291, in John P. BEAL, James A. CORIDEN, and Thomas J. GREEN (eds.), New Commentary on the Code of Canon Law, New York, Paulist, 2000, pp. 1495-1496; Francis G. MORRISEY, Commentary on Canon 1291, in Gerard SHEEHY, et al. (eds.), The Canon Law: Letter and Spirit, Collegeville, The Liturgical Press, 1995, pp. 732-733; idem, "The Alienation of Temporal Goods in Contemporary Practice," in Studia canonica, 29 (1995), p. 300; Vittorio PALESTRO, "La disciplina canonica in materia di alienzaione e di locazione (can. 1291-1298)," in Raffaello FUNGHINI (ed.), I beni temporali della Chiesa, Studi giuridici 50, Vatican City, Libreria editrice vaticana, 1999, p. 147; Jean-Pierre SCHOUPPE, Droit canonique des biens, Montreal, Wilson and Lafleur, 2008, p. 157. Significantly, the designation of stable patrimony is not precisely identified as an act of extraordinary in CONFERENZA EPISCOPALE ITALIANA, Istruzione in materia amministrativa 2005, n 53; see nn. 61-62. 15 The diocesan bishop is, however, the supervisor of the administration of parochial goods. Thomas J. GREEN writes: "The bishop, however, is also a supervisor who is bound to exercise vigilance over the administration of the goods of the juridic persons subject to him such as parishes." "The Players in the Church's Temporal Goods World", in The Jurist, 72 (2012), p. 55. 16 Indeed, the diocesan bishop can establish a particular penal law establishing as a delict the failure of an administrator to designate stable patrimony legitimately (c. 1315; see cc. 1316-1318). And, the ordinary can issue a penal precept regarding the same (c. 1319). - 91 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON to alienate them.17 The 1917 Code has listed only the first three, and had considered the act of alienation as a kind of act of extraordinary administration (see CIC/1917, canon 1495, §1). Those revising the Code, however, judged alienation to be an act distinct from administration of temporal goods: "alienation is not an act of administration."18 Therefore, a fourth aspect the Church's innate right is identified in the law. To acquire temporal goods means "to obtain them" which the Church may do in the same ways which are lawful (by natural law and positive law) for others (canon 1259). To retain temporal goods means "to keep them as possessors." To administer temporal goods means "to protect them, to help them bear fruit (e.g., revenue), and to use them for their proper ends."19 To alienate temporal goods means "to convey ownership of them to another." Acts of extraordinary administration are understood to be those acts of administration which exceed the limits and manner of ordinary administration (see cc. 1277, 1281, §§1-2). They are performed by the administrator of the juridic person (c. 1279, §1), who needs the consent of one or more other physical persons, whether as individuals or as members of group, in order to perform acts of extraordinary administration validly. Thus understood, acts of extraordinary administration are established iure universali or iure particulari.20 17 When listing these four aspects of ownership, canon 634 ' 1 uses the word retinere (to retain) rather than possidere (to possess). There is no significance to this difference. Though the 1977 Schema had used both retinere (canon 1) and possidere (canon 2), when the coetus De bonis Ecclesiae temporalibus revised the draft on 19 June 1979, it deliberately selected to use retinere consistently: Communicationes, 12 (1980), p. 396. For further studies on acts of ordinary and extraordinary administration, see Federico AZNAR GIL, "Acts de administración ordianria y extraordinaria: normas canónicas," in Revista española de derecho canónica, 57 (2000), pp. 41-70; Velasio DE PAOLIS, "Alcune osservazioni sulla nozione di amministrazione dei beni temporali della Chiesa," in Periodica, 88 (1999), pp. 91-140; John P. BEAL, "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in Between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes," in The Jurist, 72 (2012), pp. 109-129; Adrian FARRELLY, "Acta of Extraordinary Administration and Acts of Alienation", in CLSANZ Newsletter, 1 (2004), pp. 49-40; Francesco GRAZIAN, La nozione di amministrazione e di alienazione nel Codice di Diritto Canonico, Tesi Gregoriana, Serie Diritto Canonico, 55, Rome, Pontificia Università Gregoriana, 2002; Francis G. MORRISEY, "Ordinary and Extraordinary Administration: Canon 1277", in The Jurist, 48 (1988), pp. 709-726; idem, "Temporal Goods and Their Administration", in Ángel MARZOA, Jorge MIRAS and Rafael RODRÍGUES-OCAÑA (eds.), Exegetical Commentary on the Code of Canon Law, Ernest Caparros (Eng. ed.), 9 vols, Chicago, Midwest Theological Forum, 2004, vol. 2, pp. 1672-1692; David J. WALKOWIAK,, "Ordinary and Extraordinary Administration", in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, pp. 185-206. 18 Communicationes, 12 (1980), p. 396. 19 The PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR LEGISLATIVE TEXTS observes that the Legislator uses the term administration in two ways in the Code: (1) in Book I of the Code, to designate acts of governance as a function proper to ecclesiastical authority performing acts of jurisdiction (diverse from acts of legislation and acts of judgment); and (2) in Book V of the Code, to designate the administration of economic affairs, as performing a function "to preserve a patrimonial good, to help it bear fruit, and to better it." Nota La funzione dell'autorità sui beni ecclesiastici (12 February 2004), in Communicationes, 36 (2004), p. 26. 20 For extensive reflections on acts of extraordinary administration, understood as here presented, see John - 92 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON 3.2 - Acts of Extraordinary Administration iure universali The Code identifies seven acts of administration which are iure universali acts of extraordinary administration: (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) to refuse gifts of greater importance (c. 1267, §2).21 to invest surplus funds (c. 1284, §2, 6). to initiate or contest civil litigation (c. 1288). to enter some threatening contracts (c. 1295).22 to lease ecclesiastical goods (c. 1297). to invest goods of an endowment (c. 1305).23 to erect a new church building (c. 1215). Each of these activities is an act of administration, performed "non-routinely" by the administrator of the public juridic person involved, which requires the administrator to obtain consent/permission of one or more other physical persons to perform the act. The non-routine nature of the act, and the required consent/permission, demonstrate the extraordinary nature of these acts of administration. 3.3 - Acts of Extraordinary Administration iure particulari In addition to acts of extraordinary administration identified in universal law, the Code provides for the establishment of acts of extraordinary administration iure particulari. These must be clearly identified. If such an act of administration is not legitimately designated as "extraordinary", it remains "ordinary." The episcopal conference makes this designation for dioceses (c. 1277), and the statutes or the diocesan bishop makes this designation for parishes and other public juridic persons subject to him (c. 1281, §2). To perform a legitimately designated act of extraordinary administration, the Code requires that the diocesan bishop obtain the prior consent of the diocesan finance council and the college of consultors (c. 1277), and that the parochus obtain the prior written faculty (facultas) from the ordinary, without prejudice to the statutes (c. 1281, §1). A. RENKEN, "Acts of Extraordinary Administration of Ecclesiastical Goods in Book V of the CIC", to be published in Studia canonica. The Code also identifies iure universali certain acts of extraordinary acquisition (see cc. 1266, 1267, §2, and 1304, §1) and acts of extraordinary alienation (see c. 1292, §§1-2) 21 See Ronny E. JENKINS, "Gifts, Donations, and Donor Intent in the Canon Law of the Catholic Church", in The Jurist, 72 (2012), pp. 95-96; Sean O. SHERIDAN, "Endowments and Pious Wills: To Rebuild the Church", in The Jurist, 72 (2012), pp. 146-147. 22 For a study of the application of canon 1295, see John A. RENKEN, "Threatening Contracts: The Discipline and Application of Canon 1295", in Studia canonica, 45 (2011), pp. 501-519. John P. BEAL considers canon 1295 to concern an "act of extraordinary administration of greater importance." "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes", pp. 113-114, 125-127. 23 See Sean O. SHERIDAN, "Endowments and Pious Wills: To Rebuild the Church", pp. 146-148, 151-153. - 93 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON 3.4 - Acts of Extraordinary Administration: Canon 1295 Special consideration should be given to the discipline and application of canon 1295, which states: The requirements of canons 1291-1294, to which the statutes of juridic persons must also conform, must be observed not only in alienation but also in any transaction which can worsen the patrimonial condition of a juridic person. This canon establishes an act of extraordinary administration iure universali.24 The history of its development, more fully available through rather recently published issues of Communicationes (2005), demonstrates that the canon concerns contracts which involve an amount exceeding the minimum established by the episcopal conference for acts of alienation (c. 1292, §1). Every contract involving such an amount is a "transaction which can worsen the patrimonial condition of a juridic person." The same amount pertains both to all public juridic persons, poor and wealthy: it is "objectively" determined by the episcopal conference. Since this is the case, the diocesan bishop may wish to identify as acts of extraordinary administration those parish contracts involving amounts lesser than the minimum determined by the episcopal conference for acts of alienation.25 3.5 - Acts of Ordinary Administration "More Important in Light of the Economic Condition" Perhaps mention should also be made of those acts of administration which are "more important in light of the economic condition of the diocese", mentioned in canon 1277. These are acts of ordinary administration (evidence by the fact that acts of extraordinary administration are mentioned later in the same canon). The Code envisions this "special" category of acts of ordinary administration only for the juridic person of the diocese. Before the diocesan bishop performs such an act, he is to receive the counsel (not the consent) of the diocesan finance council and the college of consultors for the validity of his action. He himself determines which acts of administration are "more important in light of the economic condition." Arguably, such a category of acts of ordinary administration can be established for the parish by diocesan particular law, which would state that the parochus need the prior consultation of the parish finance council (and/or others) before he performs such acts. 26 It 24 John P. BEAL says that can on 1295 is about an "act of extraordinary administration of greater importance." "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes", pp. 113-114, 125-127. 25 For a study of the application of canon 1295, see John A. RENKEN, "Threatening Contracts: The Discipline and Application of Canon 1295", in Studia canonica, 45 (2011), pp. 501-519. 26 See John P. BEAL, "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes", pp. 113, 123-125. - 94 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON may seem more prudent and less cumbersome, however, for the diocesan bishop simply to establish acts of extraordinary administration, distinct from acts of ordinary administration, and to exhort the parochus to develop the "routine habit of full transparency"27 with the parish finance council and others in all matters involving parochial ecclesiastical goods. 4 - To Promote the Effective Involvement of the Parish Finance Council 4.1 - Universal Law on the Parish Finance Council The 1983 Code mandates a finance council or at least two financial counselors for every public juridic person (1280), but for parishes it permits only the finance council (not the optional two financial counselors). Canon 537 states: In each parish there is to be a finance council which is governed, in addition to universal law, by norms issued by the diocesan bishop and in which the Christian faithful, selected according to these same norms, are to assist the parochus in the administration of the goods of the parish, without prejudice to the prescript of canon 532. This canon is universal law for the Latin Church. It explains that the mandated parish finance council: (1) is composed of the Christian faithful; (2) has as its purpose to assist the parochus in the administration of parochial goods; and (3) can never replace the parochus as the legal representative of the parish in all juridic affairs and as the administrator of the parochial goods (c. 532).28 As is true also for the diocesan finance council (see cc. 492-492), the Code does not say that the parish finance council is merely consultative (but the Code clearly mentions the merely consultative nature of the diocesan pastoral council [c. 514, §1] and the parish pastoral council [c. 526, §2]). Nonetheless, the interdicasterial instruction on certain questions regarding the collaboration of the non-ordained faithful in the sacred ministry of 27 John P. BEAL comments: "Canon law provides the tools for improving accountability and transparency in the administration of the Church's temporal goods, the challenge of the moment is to use them." "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes", p. 129. 28 SeeAgostino DE ANGELIS, "Note per l'amministrazione dei beni parrocchiali", in Orientamenti pastorali, 32 (1984), pp. 4-5, 113-126.; J. GREÑÓN GONZÁLEZ, "El párroco y la administración de los bienes eclesiásticos", in Anuario argentino de derecho canónico, 11 (2004), pp. 397-430; Thomas J. GREEN, "Shepherding the Patrimony of the Poor: Diocesan and Parish Structures of Financial Administration", in The Jurist, 56 (1996), pp. 706-734; Matthew P. HUBER, "Ecclesiastical Financial Administrator", in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, pp. 113-124; Kevin M. MCDONOUGH, "The Diocesan and Parish Finance Council", in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, pp. 135-149; Mauro RIVELLA, "Consigliere nella Chiesa in ambito economico", in Quaderni di diritto ecclesiale, 25 (2012), pp. 390-399; Patrick J. SHEA, "Parish Finance Councils", in CLSA Proceedings, 68 (2006), pp. 169-188; Gianni TREVISAN, "L'aiuto la parroco da parte del consiglio per gli affari economici", in Quaderni di diritto ecclesiale, 25 (2012), pp. 437-447. - 95 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON priest Ecclesia de mysterio (15 August 1997),29 approved in forma specifica by Pope John Paul II, states that the parish finance council enjoys only a consultative vote and can never have a deliberative vote; that the parochus presides at council meetings; and that any actions taken by the council in his absence or against his wishes are invalid. It adds that no structure can be established to parallel or replace the parish finance council. 4.2 - Particular Law on the Parish Finance Council Moreover, canon 537 states that the diocesan bishop is to issue particular law which, within the perimeters of universal law, further defines the functioning of the parish finance council in the diocese. Obviously, such particular law would certainly address such "routine" topics as the frequency of council meetings, officers, qualifications for councilors (perhaps analogous to c. 492, §3), the method of the designation of councilors and their terms, standing and ad hoc committees, etc. In this period of rather widely spread and highly publicized instances of financial misconduct in the Church, it would be prudent for diocesan particular law to establish requirements which assure full transparency and undisputed accountability by the parochus to the parish finance council.30 To assure such transparency and accountability, for example, diocesan particular law could require the parish finance council: 29 CONGREGATION FOR THE CLERGY, et al., instruction on certain questions regarding the collaboration of the non-ordained faithful in the sacred ministry of priest Ecclesia de mysterio (15 August 1997), in AAS, 89 (1997), pp. 852-877; English available at: http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/clergy/ documents/rc_con_interdic_doc_15081997_en.html "Article 5 - The Structures of Collaboration in the Particular Church These structures, so necessary to that ecclesial renewal called for by the Second Vatican Council have produced many positive results and have been codified in canonical legislation. They represent a form of active participation in the life and mission of the Church as communion. ... § 2. Diocesan and parochial pastoral councils (cf. cc. 514, 536) and parochial finance councils (cf. c. 537) of which non-ordained faithful are members, enjoy a consultative vote only and cannot in any way become deliberative structures. Only those faithful who possess the qualities prescribed by the canonical norms (cf. c. 537, 515, §§1, 3; CCC, 1650) may be elected to such responsibilities. § 3. It is for the parochus to preside at parochial councils. They are to be considered invalid, and hence null and void, any deliberations entered into (or decisions taken by) a parochial council which has not been presided over by the parochus or which has assembled contrary to his wishes (cf. c. 536). ... § 5. Given the local situation ordinaries may avail themselves of special study groups or of groups of experts to examine particular questions. Such groups, however, cannot be constituted as structures parallel to diocesan presbyteral or pastoral councils nor indeed to those diocesan structures regulated by the universal law of the Church in canons 536, §1 and 537 (cf. cc. 536, 135, §2). Neither may such a group deprive these structures of their lawful authority. Where structures of this kind have arisen in the past because of local custom or through special circumstances, those measures deemed necessary to conform such structures to the current universal law of the Church must be taken.@ See Thomas J. GREEN, "The Players in the Church's Temporal Goods World", pp. 72-73. 30 See John P. BEAL, "Ordinary, Extraordinary, and Something in between: Administration of the Temporal Goods of Dioceses and Parishes", pp. 128-129. - 96 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON (1) to receive regular and complete accountings of all financial transactions (e.g., monthly reports of income and expenditures) (2) to offer advance counsel concerning any proposed acts of greater significance to be performed by the parochus, especially: the legitimate designation of parochial stable patrimony (c. 1291), acts of extraordinary administration (c. 1267, §2, 1288, 1295, 1297, 1215, and see c. 1281, §1) any acts of alienation (cc. 1291-1294) to be performed by the parochus. Diocesan particular law may require the parochus to present written indication of the counsel of the parish finance council in these matters to the diocesan bishop, if he is required to give the parochus the power or consent to perform the proposed act. (3) to offer advice during the development of, to review, and, as an assurance of accuracy, to affix members' signatures to: the annual parish administration report (c. 1284, §2, 8), the annual financial report (c. 1287, §1), the regularly updated inventory (c. 1283, 2-3), the annual budget (which, one would recommend, should be mandated by diocesan particular law: c. 1284, §3) (4) to offer advance counsel on various contracts binding the parish: e.g., insurance contracts (c. 1284, §2, 1), loan contracts (see c. 1284, §2, 5) investment contracts (c. 1284, §2, 6) employment contracts (see c. 1286), lease contracts (c. 1297), etc. (5) to be assured of the fulfilment of any obligations arising from an accepted gift with an attached condition or modal obligation (c. 1267, §2; see c. 1284, §2, 3), debt reduction (c. 1284, §2, 5), and non-autonomous pious foundations (c. 1303, §1, 2) (6) to have regular and open access to parish financial records (c. 1284, §2, 8) and parish legal documents (c. 1284, §2, 2, 9) (7) to inform the diocesan bishop annually, in a written document to which are affixed the signatures of its members, that the finance council has met regularly and has preformed the multiple roles assigned to it by universal and particular law In some of these examples, the parish finance council is required to provide its counsel before the parochus can perform certain functions validly (see c. 127, §1).31 This is in keeping with the 1997 interdicasterial instruction which assigns a consultative role to the parish council. 31 Other examples of possible functions of a parish finance council are proposed by Patrick SHEA, "Parish Finance Councils", pp. 180-181. - 97 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON The diocesan bishop would prudently exhort the parochus to provide routine and full disclosure to the parish finance council in all matters regarding the temporal goods of the parish - to develop a "routine habit of full transparency" in his dealings with the council.32 Why would the parochus not exhibit such a predisposition? Canon 1292, §4 forbids "those who by advice or consent must take part in alienating goods ... to offer advice or consent unless they have first been thoroughly informed both of the economic state of the juridic person whose goods are proposed for alienation and of previous alienations." It would be entirely prudent to expect (and to require) similar full disclosure to the parish finance council as it performs all its invaluable services. 5. To Provide Diocesan Assistance: Particular Law, Special Instructions, and Other Practical Diocesan Assistance 5.1 - Diocesan Particular Law33 Those drafting the 1983 Code were aware that their work would be complimented by various particular laws. Indeed, subsidiarity is one of the principles giving the revision of the 1917 Code, especially in the area of temporal goods. Guiding Principle 5 of the 1967 Synod of Bishops extolled the importance of particular law, especially concerning temporal goods: The importance of these particular laws is to be more accurately described in the new Code of Canon Law especially in temporal administration, since the governance of temporal goods must be ordered for the most part according to the laws of each nation.34 32 See Victor G. D'SOUZA, "General Principles Governing the Administration of Temporal Goods of the Church, inVictor G. D'SOUZA (ed.), In the Service of Truth and Justice: Festschrift in Honour of Prof. Augustine Mendonça, Professor Emeritus, Bangalore, Saint Peter's Pontifical Institute, 2008, pp. 467498. 33 Much of this is a re-working of John A. RENKEN, "Particular Laws on Temporal Goods", in Studies in Church Law, 4 (2008), pp. 447-454. See also idem, "The Parochus as the Administrator of Parish Property", in Studia canonica, 43 (2009), pp. 487-520. 34 In April 1967, a central committee of the Pontifical Commission for the Revision of the Code of Canon Law developed ten principles to direct the task of revising the code. These principles were approved (with a few modifications) by the 1967 Synod of Bishops. Principle 5 on subsidiarity extolled the importance of particular law, especially concerning temporal goods: "The importance of these particular laws is to be more accurately described in the new Code of Canon Law especially in temporal administration, since the governance of temporal goods must be ordered for the most part according to the laws of each nation." Communicationes, 1 (1969), p. 81. The Synod of Bishops met September 30October 4, 1967. They voted in favor of principle 5: 128 placet, 58 placet iuxta modum, 1 non placet. Communicationes, 1 (1969), pp. 99-100. For reflections on the application of subsidiarity in the 1983 Code, and particularly in its Book V, see: Phillip J. BROWN, "The 1983 Code and Vatican II Ecclesiology: The Principle of Subsidiarity in Book V", in The Jurist, 69 (2009), pp. 583-614. - 98 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON The Code envisions that particular laws governing temporal goods be established by the episcopal conference35 and by the bishops of an ecclesiastical province.36 In addition, the Code says that the diocesan bishop must establish of diocesan particular law concerning temporal goods in six canons,37 and that he can establish diocesan particular law in five canons.38 In addition to the matters identified in the Code and especially to the diocesan particular law governing parish finance councils already extensively treated above, it may be appropriate for the diocesan bishop to consider establishing diocesan particular law in several other matters relating to the temporal goods of a parish, especially: (1) Diocesan Particular Law on Alienation of Parish Property. Canons 1291-1294 concern alienation of parochial stable patrimony valued over an amount determined in advance by the episcopal conference, and indicate from whom consent for such alienation is required. The Code requires no consent for the alienation of parochial stable patrimony valued under the minimum amount established by the episcopal conference, but diocesan particular law may require such consent, whether for all alienation or perhaps only for alienation involving property which surpasses a specific amount which is less than that established by the episcopal conference.39 Such diocesan 35 See canons 1262; 1265, §2; 1272; 1277; 1292; and 1297; see also canon 1274, §2. 36 See cc. 1264, 1; 1264, 2; and 952. 37 See canons 537; 1277; 1281, §2; 1287, §2; 1303, §1, 2; and 1304, §4. 38 See canons 1263; 1266; 1274; 1284, §3; and 531. 39 The particular law for canon 1292, §1 for the United States establishes a minimum amount for parishes and other public juridic persons subject to the diocesan bishop which is less than the minimum amount established for parishes: "1. The maximum limit for alienation and any transaction which, according to the norm of law, can worsen the patrimonial condition is $7,500,000 for Dioceses with Catholic populations of half a million persons or more. For other Dioceses the maximum limit is $3,500,000 (cf. can. 1295). 2. The minimum limit for alienation and any transaction which, according to the norm of law, can worsen the patrimonial condition is $750,000 for Dioceses with Catholic populations of half a million persons or more. For other Dioceses the minimum limit is $250,000. 3. For the alienation of property of other public juridic persons subject to the Diocesan Bishop, the maximum limit is $3,500,000 and the minimum limit is $25,000 or 10% of the prior year's ordinary annual income, whichever is higher." The diocesan bishop can establish by particular diocesan law which will require his permission for the alienation of parish property valued at even a lower minimum amount. USCCB, Canon Law Complementary Norms, "Canon 1292,§1 - Minimum and Maximum Sums, Alienation of Church Property", available at: http://www.usccb.org/beliefs-and-teachings/what-we-believe/canon-law/ complementary-norms/canon-1292-1-minimum-and-maximum-sums-alienation-of-church-property.cfm - 99 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON particular law would require at least the consent of the diocesan bishop for the validity of such an alienation. This diocesan particular law may also require that the parochus present to the diocesan bishop or another local ordinary in writing the consultative votum of the parish finance council regarding the proposed act of alienation. (2) Diocesan Particular Law on Acts of Extraordinary Administration Involving Parish Property. Canon 1281, §2 says that iure particulari acts of extraordinary administration of parochial ecclesiastical goods are defined either by parochial statutes or, if the statutes are silent, by the diocesan bishop. Canon 1281, §1 requires the parochus to obtain the prior written faculty from the local ordinary before he performs such acts. The diocesan particular law may require the parochus to present to the local ordinary in writing the consultative votum of the parish finance council regarding the proposed act of extraordinary administration. (3) Diocesan Particular Law on Leasing Parish Property. Canon 1297 says that the episcopal conference is to establish particular law on leasing ecclesiastical goods, and to identify the ecclesiastical authority competent to give consent for lease contracts. Within the limits of this particular law for the territory of the episcopal conference, diocesan particular law may require the parochus to present to the diocesan bishop or another local ordinary in writing the consultative votum of the parish finance council regarding the proposed lease contract. (4) Diocesan Particular Law on Parish Capital Campaigns. Diocesan particular law may require the prior written permission of the diocesan bishop before any capital campaign is initiated in a parish. The diocesan particular law may require the parochus to present to the diocesan bishop in writing the consultative votum of the parish finance council regarding the parish capital campaign. (5) Diocesan Particular Law Requiring Parish Statutes. Diocesan particular law may require the creation of statutes for parishes, and may expect that these statutes correspond as closely as possible to related civil documents. This will allow the same norms to govern the parochus and the parish in the secular forum and the ecclesiastical forum. It will be very important that these documents identify any actions for which the parochus needs the consent of the diocesan bishop in order for his action to be valid in both fora. - 100 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON (6) Diocesan Particular Law on Parish Audits. Diocesan particular law may mandate periodic (internal or external) audits of parish financial records and periodic reviews of parish financial practices. The law may require that the person(s) conducting the audits/reviews be an official of the diocesan curia, and that the conclusions of the audits/reviews be presented to the parochus and competent diocesan authority (e.g., the diocesan bishop, the vicar general, the diocesan finance officer, etc.) (7) Diocesan Particular Law on Designation of Stable Patrimony. Diocesan particular law may identify those parochial ecclesiastical goods which are to be designated as stable patrimony explicitly by the parochus. Such designation is an act of ordinary administration, which is rightly performed routinely by the parochus after the parish has been established. Mandating the explicit designation of stable patrimony avoids the confusion and disputes which arise when an ecclesiastical good becomes stable patrimony implicitly by regular usage, as mentioned already. In addition, depending on local circumstances, diocesan particular law may also address a multitude of other important issues: e.g., minimum insurance coverages (c. 1284, §2, 1˚); civil legal protections (c. 1284, §2, 2˚); method of handling collections (c. 1284, §2, 4˚); mandated debt reduction schedule (c. 1284, §2, 5˚); parochial archives (c. 1284, §2, 9˚), etc. 5.2 - Diocesan Special Instructions40 Canon 1276, §2 requires the local ordinary to issue special instructions (peculiares instructiones)41 to order the entire matter of the administration of ecclesiastical goods. Canon 34 describes the purpose, scope, and binding authority of instructions: instructions clarify the prescripts of laws and elaborate on and determine the methods to be observed in fulfilling them; they do not derogate from laws, and if they cannot be reconciled with laws, they lack all force. Instructions are given by those with executive power within the limits of their competence for the use of persons who have the duty to see to the execution of laws. Instructions cease having force when revoked, explicitly or implicitly, by the authority who issued them or by that authority's superior, or by the cessation of law for whose clarification or execution they were issued. 40 This is largely a reproduction of John A. RENKEN, "The Parochus as Administrator of Parish Property", pp. 516-518. See also Judith O'BRIEN, "Instructions for Parochial Temporal Administrators", in Catholic Lawyer, 41 (2001), pp. 113-143. 41 The term instructio is modified by the adjective peculiaris only in canon 1276 '2. - 101 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON Special instructions issued by the local ordinary will assist the parochus in performing his many administrative munera. It is very common and useful for these special instructions to be assembled into a "parish financial manual" by the competent diocesan authority to assist the parochus. Special instructions may, for example, address the following issues: 42 (1) the manner of managing all aspects of Mass offerings (cc. 945-958) (2) the manner of requesting a special parish collection (c. 1266) (3) the manner of obtaining the permission of the local ordinary to refuse a gift of greater importance for a just cause (c. 1267, §2) (4) the manner of obtaining the permission of the local ordinary to accept a gift to which is attached a modal obligation or condition (c. 1267, §2) (5) the manner of obtaining the written faculty from the local ordinary to perform an act of extraordinary parish administration (c. 1281, §1) (6) the manner of taking the oath to administer parochial goods well and faithfully, and before whom the oath is to be taken (c. 1283, 1˚) (7) the format for inventories of parochial property, and the frequency with which they are to be updated regularly (c. 1283, 2˚-3˚) (8) the manner of obtaining adequate insurance coverage (c. 1283, §2, 1˚) (9) the manner of assuring the civil legal protection of parish property (c. 1283, §2, 2˚; see c. 1283, §2, 3˚) (10) the manner of collecting and securing parish revenue (c. 1283, §2, 4˚)42 (11) the manner of developing a workable debt reduction schedule (c. 1283, §2, 5˚) (12) the manner of obtaining the consent of the local ordinary to invest surplus parish revenue (c. 1283, §2, 6˚) or endowed funds (c. 1305) This instruction may particularly address how routine parish collections for regular Church support (i.e., "the Sunday collections") are to be secured, counted (by rotating "teams" of "collection counters"), and deposited. - 102 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON (13) the format for parish records of income and expenditures (c. 1283, 2, 7˚) (14) the manner of presenting the annual parish administration report, and its format (c. 1283, §2, 8˚) (15) the manner of presenting the annual parish financial report to the local ordinary which he will present for examination to the diocesan finance council, and its format (c. 1287, §1)43 (16) the manner of maintaining parochial archives on property rights (c. 1283, §2, 9˚; see cc. 491, §1, 535, §4) (17) the format for annual parish budgets, if they are mandated by diocesan particular law (c. 1283, §3) (18) the manner of complying with civil employment laws according to the principles handed on by the Church, and of providing a just and decent wage to Church workers (c. 1286) (19) the manner of rendering an account to the faithful about their offerings to the parish, and the format of the report (c. 1287, §2)44 (20) the manner of obtaining written permission to initiate or to contest civil litigation (c. 1288) (21) the manner of legitimately designating stable patrimony (c. 1292; see c. 1285) (22) the manner of obtaining permission to alienate the stable patrimony of the parish (cc.1291-1294) (23) the manner of obtaining permission to enter a contract which may threaten the patrimonial condition of the parish (c. 1295) (24) the manner of entering a contract to lease property owned by the parish (c. 1297) (25) the manner of informing the local ordinary of the parish's having received a pious will, whether mortis causa or inter vivos (c. 1301), or a pious trust (c. 1302), and the manner of proceeding 43 Thomas John PAPROCKI, and Richard B. SAUDIS, "Annual Report to the Diocesan Bishop", in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, pp. 175-183. 44 Royce R. THOMAS, "Financial Reports to the Faithful",in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, pp. 165-174. - 103 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON (26) the manner of establishing a parish non-autonomous foundation, and all the legal requirements associated with its establishment (c. 1303, §1, 2˚; see cc.1304-1307) (27) the manner of seeking to reduce (c. 1308) or transfer (c. 1309) Mass obligations (28) the manner of seeking to reduce, moderate, or commute pious wills not involving Mass offerings (c. 1310) (29) the manner of determining if a parochial good is sacred (see c. 1269), or precious for artistic or historical reasons (cc.1270, 1292, §2) (30) the manner of conducting an internal audit of parish financial records and an internal review of parish financial practices, etc. 5.3 - Other Practical Diocesan Assistance in the Care of Temporal Goods45 Obviously, diocesan assistance is also provided through the establishment of diocesan particular law and the issuing of special instructions concerning temporal goods, mentioned above. Nonetheless, it would seem that the greatest possible assistance able to be offered by the diocesan bishop to assure the proper care of Church property is formation in Church law on temporal goods provided for all the Christian faithful, especially parochi and others who serve in leadership ministries in parishes (particularly parish finance councilors). This formation would address the ecclesiastical laws (universal and particular) and civil laws governing parish property. It would also explain all the diocesan special instructions whose purpose is to assist the parochus in executing the law. Similar formation can be offered for those preparing for diaconal and presbyteral ordination. In addition, there are multiple other means whereby the diocesan bishop and his immediate collaborators can assist the parochus in his munus as the administrator of parochial goods. Some examples come to mind: (1) 45 Critical Analysis of Annual Parish Reports. The diocesan bishop can assist the parochus by providing a critical analysis of the annual parish administration report (c. 1284, §2, 8) and the annual parish financial report (c. 1287, §1). The Code requires that the diocesan finance council review the annual parish financial reports; the parochus submits these reports to the local ordinary, who presents them for examination to the diocesan finance council; any contrary This is largely a reproduction of John A. RENKEN, "The Parochus as Administrator of Parish Property", pp. 518-520. - 104 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON custom is expressly reprobated (c. 1287, §1). The involvement of the diocesan finance council may be a great service to the parochus in countless ways: by recommending modifications in parish spending, by suggesting new methods of generating income, by highlighting areas of concern, etc. The serious study of the annual parish financial report (and of the annual parish administration report) can also be an incentive to avoid various kinds of financial malfeasance. 46 (2) Regular Review of Parish Archives and Documents. The diocesan bishop can assist the parochus by reviewing periodically, personally or through his delegate, the parish archives and documents, especially those dealing with finances and temporalities. The Code also requires that the diocesan bishop (or his designated priest, such as the vicar forane)46 visit each parish at least every five years (c. 396, §1). At the time of parochial visitation or at another time, he (or his delegate) is to inspect the parish archive, which is to preserve parochial registers, episcopal correspondence, and documents which must be preserved (c. 535, §4) Among the documents contained in the archive are those containing financial information, civil property records, etc. The regular review of the parish archive can be an incentive to maintain it accurately, and can provide the parochus with further guidance in protecting and arranging it. (3) Establishment of Parish Statutes. The diocesan bishop can assist the parochus by approving statutes for each parish, even though statutes are not strictly required by law (as mentioned at the beginning of this article). Parish statutes will clearly define important issues concerning the care of parish goods by the parochus. (4) Applying the Discipline of Book VI. The diocesan bishop can assist the parochus and the entire Catholic community by implementing the provisions of Book VI dealing with delicts involving "financial malfeasance." Many suspect that financial malfeasance will be the next great scandal in the Church; many more would suggest that this serious scandal has already started. A serious approach to the discipline of Book VI may provide incentive to the parochus and to all charged with care of church property to perform their munus responsibly and honestly. In many dioceses, the vicar forane is designated by the diocesan bishop to inspect the parish archive and financial affairs on a regular basis (whether every five years or even annually). The vicar forane has the duty and right to see "that the parochial registers are inscribed correctly and protected appropriately" and "that ecclesiastical goods are administered carefully" (c. 555, §1, 3˚). Moreover, he is "to make provision so that, on the occasion of illness or death [of the parochus], the registers, documents, sacred furnishings, and other things which belong to the parish are not lost or removed" (c. 555, §3). - 105 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON 6 - To Apply Penal Law on Financial Malfeasance All of us are painfully aware of, and oftentimes greatly embarrassed over, media reports of financial malfeasance at all levels of the Church. We hear stories of (arch)bishops who resign their office after financial negligence, of Vatican officials being investigated or incarcerated for financial malfeasance, of long-term and trusted diocesan and parochial employees being charged with theft, of dioceses becoming bankrupt, of the misdirecting of assets of parishes which are said to be "closed", 47 etc. Such reports prompt a refreshed understanding of the penal canons on financial malfeasance, and of the appropriateness of their application in practice. We are aware that the Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts is in the process of revising Book VI: Sanctions in the Church. The praenotanda of the reserved 2011 Schema recognitionis Libri VI Codicis iuris canonici,48 published in Communicationes,49 remarks that penal law must be understood as a pastoral instrument "able to be combined with the charity required by pastoral action." The Schema identifies as the first criterion for revising Book VI: First, we have proposed to elaborate the penal system as an instrument of governance which the pastors can have at hand in exercising their responsibilities of governance for the good of the People of God. Recourse to the penal system is indeed a requirement of pastoral charity and the salvation of souls demands that its exercise not be delayed. Therefore, the revision envisioned endeavors to stimulate ecclesiastical authorities so that, as often as it is opportune, they employ penal discipline. For this reason, amended are some expressions which appear repeated in various canons of the 1983 Code and which appear to dissuade pastors from making recourse to penal law, but instead to use other means for solving questions.50 The Pontifical Council urges diocesan bishops to use penal law, promptly and pastorally, when the occasion arises, for the manifestation of pastoral charity and the salvation of souls. While canon 1341 sees penalties as a kind of "last resort" in the effort to repair scandal, restore justice, reform the offender, after a delict has been committed, the discipline of canon 1341 does not imply that diocesan bishops should never (or only most rarely) resort to penalties. The appropriate resorting to penalties would certainly apply to various delicts of financial malfeasance. 47 See CONGREGATION FOR THE CLERGY, circular letter with "Procedural Guidelines for the Modification of Parishes, the Closure or Relegation of Churches to Profane but not Sordid Use, and the Alienation of the Same" (30 April 2013), prot. N. 20131348. 48 PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR LEGISLATIVE TEXTS, Schema recognitionis Libri VI Codicis iuris canonici (reservatum), Vatican City, Typis polyglottis vaticanis, 2011. 49 Communicationes, 43 (2011), p. 317-320. 50 Communicationes, 43 (2011), p. 318. [Author's translation]. - 106 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON The Code does not contain a delict which explicitly mentions "financial malfeasance", which we understand here as a generic reference to such acts as stealing, embezzling, misusing designated goods, etc. The Code does, however, identify the delict of canonically invalid alienation of ecclesiastical goods, which is to be punished with a just penalty (c. 1377). It also identifies as delicts various actions which can be related to financial malfeasance: i.e., impeding the use of ecclesiastical goods (c.1375); simony (c. 1380); illicit profit from Mass offerings (c. 1385); bribery (c. 1386); and the production and use of falsified documents (c. 1391).51 All these delicts involve ferendae sententiae penalties (c. 1314) which are indeterminate (c. 1315, §2) and which, therefore, cannot be perpetual penalties (c. 1349). One cannot be removed from office for committing these delicts, since removal is a perpetual penalty. If clear acts of "financial malfeasance" are to be punished, these must be understood as violating the delict canon 1389: §1. A person who abuses an ecclesiastical power or function is to be punished according to the gravity of the act or omission, not excluding privation of office, unless a law or precept has already established the penalty for this abuse. 51 For further reflections on financial malfeasance, see Elizabeth MCDONOUGH, "Addressing Irregularities in the Administration of Church Property", in Kevin E. MCKENNA, Lawrence A. DINARDO, and Joseph W. POKUSA (eds.), Church Finance Handbook, Washington, CLSA, 1999, pp. 223-243; Thomas J. GREEN, "The Players in the Church's Temporal Goods World", p. 71; Francis G. MORRISEY, "Financial Malfeasance and Canon Law", presented to the Diocesan Fiscal Management Conference, Houston, Texas, 25 September 2012 (unpublished); John A. RENKEN, "Penal Law and Financial Malfeasance", in Studia canonica, 42 (2008), pp 5-57. The following chart summarizes the existing delicts related to "financial malfeasance" in the current law: CANON DESCRIPTION OF DELICT PRECEPTIVE / FACULTATIVE PENALTY 1389, §1 Malicious Abuse of Authority Preceptive Indeterminate penalty - according to the gravity - not excluding privation of office - unless another penal law or precept applies 1389, §2 Negligent Exercise of Authority Preceptive Indeterminate just penalty 1391 Production and Use of False Documents Facultative Indeterminate just penalty 1375 Impeding Use of Ecclesiastical Goods Facultative Indeterminate just penalty 1377 Invalid Alienation of Ecclesiastical Goods Preceptive Indeterminate just penalty 1380 Simony Preceptive Censure: interdict or suspension 1385 Illegitimate Profit from Mass Offerings Preceptive Censure or indeterminate just penalty 1386 Bribes Preceptive Indeterminate just penalty - 107 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON §2. A person who through culpable negligence illegitimately places or omits an act of ecclesiastical power, ministry, or function with harm to another is to be punished with a just penalty. This canon establishes two distinct delicts which may be involved in "financial malfeasance:" (1) malicious abuse of authority in office, and (2) criminal negligence in exercising an office. Most likely, one guilty of "financial malfeasance" would violate canon 1389, §1, which permits the penalty of deprivation of office, a perpetual expiatory penalty. Of course, one could also apply the delict of canon 1399 to acts of "financial malfeasance." This canon, of course, is limited inasmuch as it allows punishment with an indeteminate just penalty which cannot be a perpetual penalty (c. 1349). Therefore, canon 1399 does not permit the removal from office for financial malfeasance, since this removal is perpetual. Moreover, one will recall that among the causes for the administrative (i.e., nonpenal) removal of a parochus is the "poor administration of temporal affairs with grave damage to the Church whenever another remedy to this harm cannot be found." Indeed, one can hope that a revised Book VI would establish clearly the delict of "financial malfeasance" (perhaps as a modification of canon 1377 on invalid acts of alienation). One would propose a revised canon 1377 to establish as delictuous both "financial malfeasance" and invalid alienation, which would subject the offender to a perpetual expiatory penalty of perpetual deprivation of office, and which would also subject him or her to a censure if the offender refuses to make restitution (see c. 128). Indeed, such provisions perhaps should also apply whenever a Catholic violates some or all of the other canons related to "financial malfeasance", mentioned above. Any application of penal law, of course, requires a preliminary investigation "unless such an inquiry seems entirely superfluous" (c. 1717, §1). Only after a preliminary investigation has occurred (after sufficient elements have been gathered), must the ordinary decide (1) whether or not to initiate a penal process; (2) whether such a process is expedient in light of canon 1341; and (3) whether the process should be judicial (as preferred) or extrajudicial (c. 1718, §1). The acts of the preliminary investigation are to be preserved in the secret archive of the curia if there is no penal process, or if they are not needed for the penal process (c. 1719). It is important to underscore that the existing Code requires a preliminary investigation before the ordinary makes any determination related to the discretion provided by canon 1341. A renewed awareness of the existence of penal law and a refreshed understanding of its purpose as an instrument of pastoral charity assist in the care of Church property. - 108 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON Conclusion As I mentioned at the beginning, I am grateful for the opportunity to have highlighted today what I propose to be six contemporary critical issues in the care of Church property, particularly parish property. I believe that the appropriate addressing of these issues reflects and supports the Church's commitment to be prudent stewards of ecclesiastical goods. The Church does not find its fulfilment in this world, much less in the false comfort of the accumulation of worldly goods. Nonetheless, the Church needs temporal goods to fulfil its mission in the world, and administrators of the Church's temporal goods must fulfil their important munus according to the Church's law. Church property assists in performing the truly important works of the Church: the ordering of divine worship, the decent support of the clergy and other ecclesial ministers, and the works of the sacred apostolate, especially works which favour the needy in a Church designed to be of the poor and for the poor (see c. 1254, §2). I would hope that these reflections somehow assist in promoting these noble purposes. Monsignor John A. Renken, P.H. M.A. (Civil Law), S.T.D., J.C.D. Professor of Canon Law Saint Paul University Ottawa, Ontario Canada - 109 - CANADIAN CANON LAW SOCIETY / SOCIÉTÉ CANADIENNE DE DROIT CANONIQUE 28 - 31 OCTOBER/OCTOBRE 2013 - SUDBURY, ON - 110 -