Running head: Executive Person

advertisement

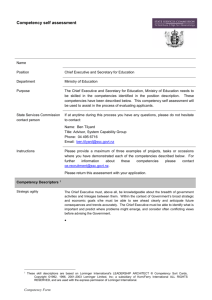

Running head: Understanding Executive Jobs EXECUTIVE JOBS ARE NOT CREATED EQUAL: HOW JOBS SHAPE THE COMPETENCIES DISPLAYED BY OUTSTANDING EXECUTIVES Guorong Zhu Hay Group 116 Huntington Ave. Boston, MA 02116 Phone: 617-425-4519 E-mail: Guorong_Zhu@Haygroup.com Steven B. Wolff Hay Group 116 Huntington Ave. Boston, MA 02116 Phone: 617-425-4525 E-mail: Steven_Wolff@Haygroup.com Signe Spencer Hay Group 116 Huntington Ave. Boston, MA 02116 Phone: 617-425-4508 E-mail: Signe_Spencer@Haygroup.com Understanding Executive Jobs 2 ABSTRACT This study sheds light on one cause of executive failures by looking at executive jobs through the lens of Person-Job fit theory. We examine two dimensions of executive jobs – degree of accountability for organizational results and complexity of problem solving. We show, with an international sample of 360 individuals that effective executives display different competencies depending on the degree of accountability and the complexity of problem solving that are characteristic of the job. We explore implications of this research for creating a better match between an executive and the job – increasing the likelihood that executives will be successful in their roles. Understanding Executive Jobs 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank Vanessa Druskat, Elizabeth Craig, Tim Hall, and Ruth Wageman for their insightful and helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. We also thank the expert coders who helped us characterize executive jobs and code interview transcripts. Understanding Executive Jobs 4 EXECUTIVE JOBS ARE NOT CREATED EQUAL: HOW JOBS SHAPE THE COMPETENCIES DISPLAYED BY OUTSTANDING EXECUTIVES One of the top challenges faced by leaders at the top of organizations is finding the right executives to fill vacancies in the organization’s leadership (e.g., Barrington & Silvert, 2004). Increasingly high turnover rates among corporate executives are making headline news (e.g., Gerdes, 2007; Mogel, 2006). This challenge seems to be growing as the current generation of leaders begins to retire, and organizations frequently fail to find executives who excel in leadership jobs (Economist, 2003a, 2003b). Increasing numbers of organizations are reporting serious issues with leadership succession, as their current selection practices result in unsuccessful placements either because the manager fails to deliver results (Ulrich, Zenger & Smallwood, 1999) or he or she is unhappy in the job and leaves (Pomeroy, 2005). Because executive failures can be very costly for a company (Fernandez-Araoz, 2005), the need to find the right executives is imperative. In this study we use Person-Job fit theory as a lens through which to examine the problem of matching executives to the job. The Person-Job fit perspective states that successful job performance requires a person’s abilities to be matched to the demands of the job (Kristof, 1996). Doing so, however, presumes that we adequately understand the demands of the job and the matching characteristics of the person that lead to successful performance. Research on matching people to jobs is extensive (see Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman & Johnson, 2005; Kristof), however, the understanding of executive jobs as compared with frontline task-performing roles or lower supervisory jobs is seriously under-nuanced and often ineffective (Economist, 2003a, 2003b; Fernandez-Araoz, 1999). As Finkelstein & Hambrick (1996) state in their book on strategic leadership, research on executive leadership often assumes that the difficulty of the job Understanding Executive Jobs is relatively constant across a variety of roles. The early derailments of several previously successful leaders at high-profile companies, e.g., Xerox, P&G, Lucent (Conger & Nadler, 2004), illustrates the potentially costly consequences of not understanding differences in executive jobs. To avoid failures related to a mismatch of job demands with the executive’s capabilities, we must first gain a more nuanced perspective of how executive jobs vary. The field study presented here examines two dimensions of executive jobs that create varying demands on executives but have typically not been considered when trying to match an executive to the job: (1) the degree of accountability of the job for the organization’s financial results, i.e., the extent to which an executive has direct control over the factors affecting profitability, such as type and price of products, efficiency of production, sales strategies, etc.; and (2) the degree of overall complexity in problem solving associated with the job. We will argue that differences in these dimensions create different job demands on persons, and thus require different abilities for success. This study proceeds from the assumption that the success of outstanding performers in different jobs occurs because those executives have and demonstrate specific abilities that fulfill the demands of their jobs. We study 360 outstanding performers in a range of executive jobs from 7 regions of the world, including 42 organizations in 12 industries. We test whether abilities displayed by outstanding performers, defined as those nominated in the top 10% of executives in the company, vary with the characteristics of their specific jobs. Person-Job Fit Person-Job fit theory offers one lens through which we can understand the relation of competencies displayed by outstanding performers and job characteristics. According to the 5 Understanding Executive Jobs 6 theory, job performance is related to how well a person is matched to the job (Kristof, 1996). Thus, if we assume outstanding performers are matched to their jobs, then Person-Job fit theory leads to the conclusion that executives in jobs with different demands will display different competencies. When executives are moved to new jobs, new demands are placed on the executive. Thus, failure when making a transition from one role to another can be ascribed, in part, to a mismatch between the demands of the new job and the characteristics of the executive. When examining fit between a person and their job it is important to keep in mind that there are many kinds of fit. Person-Job fit is a subset of the broader Person-Organization fit; and within Person-Job fit one can look at matches between the demands of the job and the abilities of the person (demands-abilities fit) as discussed above. However, other perspectives on fit are also possible, e.g., matching what the person needs from the job with what the job supplies (needssupplies fit) (Kristof, 1996). At the executive level, various types of fit have been examined; however none of the research looks at specific characteristics of the executive’s job and the abilities required by those jobs. In fact, the only study we found that uses a framework that includes specific characteristics of the job to classify an executive’s role was done by Drazin and Rao (1999) but they study succession rather than fit with capabilities. They classify executive roles based on two characteristics of the job: distance from the top of the organization and degree of job specialization. The lack of Person-Job fit research examining specific characteristics of executive jobs is somewhat surprising given the importance of the job and the potential of such a fit to explain differences in performance. For example, a comprehensive meta-analysis of Person-Job fit research by Kristof-Brown, Zimmerman, and Johnson (2005) found that matching the demands of a job to a person’s abilities explains 30.6% of the variance in job performance and 40.9% of Understanding Executive Jobs 7 the variance in job satisfaction. Very little of the research identified in the meta-analysis, however, was focused on executives. At the executive level, research has examined various types of fit but little of it focuses specifically on the demands-abilities form of Person-Job fit. For example, studies have examined the fit between an executive’s industry, business, and functional experience/expertise and the organization’s context such as stage in the life-cycle (Gupta & Govindarajan, 1984), characteristics of the business cycle (Bassett, 1969; Dess & Picken, 2000), and organizational strategy (Beal & Yasai-Ardekani, 2000; Guthrie & Datta, 1997; Thomas & Ramaswamy, 1996). These are important forms of Person-Job matching but they do not identify abilities required to meet the unique demands of a particular job. Other studies examine required abilities that are common to all leadership positions without analyzing the specific job. Common leadership skills identified include: communication, managing change, networking (Raelin, 1997), conflict management, team building, integrity (Jordan & Schraeder, 2003), self-awareness, adaptability, and learning (Hall & Moss, 1998). Similarly, the fact that executives need specialized skills related to their area of technical expertise is widely acknowledged (Castanias & Helfat, 1991; Fernandez-Araoz, 2005; Jordan & Schraeder, 2003), but there is little recognition that all jobs requiring the application of these specialized skills are not the same (Hayes, Rose-Quirie & Allinson, 2000). There are also studies that examine specific positions but do not examine the job in a way that can be generalized beyond the role being studied, e.g., project managers (Dainty & Cheng, 2005), sports managers (Horch, 2003), or safety managers (Blair, 1999). When the specific job is considered at the executive level, a match is often made by placing the job into a general category, e.g., level in the organization (O'Roark, 2002), functional Understanding Executive Jobs 8 area (Pavett & Lau, 1983), or execution of similar strategies (Beal & Yasai-Ardekani, 2000) and then looking for abilities that are commonly displayed by people with jobs in those categories. This approach can lead to mismatches between the job and an executive because all jobs in the same general category are not, in fact, the same. The CEO of a small company faces very different challenges than a CEO of a Fortune 500 company. An IT manager in a bank has a very different job than an IT manager in a consulting firm. Although there is value to matching an executive’s abilities to a job based on factors common across jobs, this approach needs to be supplemented by matching the executive’s abilities to the specific characteristics of the particular job. Characteristics of Executive Jobs Although there are potentially many characteristics that could be considered when defining executive jobs, the purpose of our research is not to define all important characteristics of the executive job but to demonstrate that there are indeed job characteristics that lead to differences in the competencies displayed by outstanding performers. Because of the limited research on demands-abilities Person-Job fit for executives and specific characteristics that can be used to classify executive jobs, we see this study as a first step toward demonstrating the need to better understand specific characteristics of executive roles and thus spark additional research that can help us more fully characterize important aspects of the executive’s job and ultimately reduce executive failures. In choosing job characteristics to examine for this study we sought a set of characteristics that were neither so specific that they could not be generalized across executive positions nor so general that they would not adequately differentiate among executive roles. We also were interested in aspects of the executive job that have been treated in the research literature, albeit Understanding Executive Jobs 9 not necessarily as a means of matching an executive’s abilities with the demands of the job. To define the dimensions of the executive job we took advantage of the existing methodology called the “Guide Chart Profile,” which is one of the most commonly used job evaluation method in practice (Armstrong, 2006; Gomez-Mejia, Balkin & Cardy, 2007). It includes two characteristics that can be used to define any executive job: the degree of complexity of problem solving required by the job and the degree of accountability for bottom-line organizational results (Hay, 1958). Problem-solving is the “use of the know-how required by the job, to identify, define, and resolve problems” (Bellak, 1984, p. 15/2). Accountability represents the “measured effect of the job on the end results of the organization,” usually the financial or bottom-line results (Bellak, p. 15/4). Because problem-solving complexity and degree of accountability are aspects of work common to all jobs, but which also vary systematically across jobs, they can be used to analyze any executive job independent of the job title or organization (Skenes & Kleiner, 2003). In the next sections, we discuss these dimensions in more detail. Both dimensions are theoretically continuous and are discussed as such in the following sections; however, as we explain in the methods section, in practice the dimensions are divided into discrete categories. Problem solving complexity. Complexity in the use of data is a characteristic commonly used to distinguish one job from another. For example, the Dictionary of Occupational Titles (U.S. Department of Labor, 1991) classifies jobs into seven levels of complexity based on the use of data. Executives use data and knowledge to identify and solve organizational problems and make strategic decisions (Mumford, Zaccaro, Harding, Jacobs & Fleishman, 2000). Executive jobs, therefore, can be arrayed along a dimension that characterizes the degree of complexity in problem solving required by the job. Some executive jobs are routine with clearly Understanding Executive Jobs 10 defined problems. For example, an executive running a large manufacturing operation where the company is in a relatively stable environment, not engaged in a turnaround, and has already adopted efficiency measures such as six sigma needs to make relatively routine and non-complex decisions. Other executives operate in an environment that is new and uncharted with few guidelines for solving problems and making decisions (Bellak, 1984). For example, the head of human resources in a company that is expanding into three new countries on different continents must make some complex and difficult decisions as policy is formulated for the organization. A number of factors affect the degree of complexity in problem solving, e.g., the size and scope of the job as well as the length of time that the executive must look ahead in making strategic decisions. The degree of complexity in problem solving is a characteristic of the job itself and can be estimated independent of job title, organization, industry, or the person holding the job. Accountability for organizational results. The degree to which a person in a given job is accountable for organizational results is a second characteristic that can be used to distinguish one job from another. It identifies the relevant and important differences between jobs in terms of how each job impacts the end results of business performance (Church & Waclawski, 2001). A 2003 survey of job evaluation practices found that accountability is one of the most frequently used factors to analyze and evaluate jobs across companies (Armstrong, 2006). The conceptualization of jobs as having varying degrees of accountability for organizational results has a long history dating back to classic organization theory. The line-staff form of organization structure was developed to reconcile the need for specialized expertise in the managerial decision making process with the need to maintain clarity, responsibility, and accountability for organizational results (Galbraith, 1977). At one end of the accountability dimension are jobs with direct responsibility for organizational results, e.g., typical operations Understanding Executive Jobs 11 roles such as a manufacturing executive in a company whose business is the production of goods. Such jobs are typically referred to as “line” jobs (Browne & Golembiewski, 1974; Pfeffer, 1977). At the other end of the accountability dimension are those jobs that provide expertise to the line manager, e.g., support or advisory roles such as Human Resources director or Legal Counsel in a manufacturing organization. These jobs are often referred to as “staff” jobs (Browne & Golembiewski; Pfeffer) and are only indirectly accountable for organizational results by increasing the effectiveness of line managers and by providing services the business needs to operate but which line managers do not have the expertise to provide. Executive Abilities We now turn to identifying a set of executive abilities that we hypothesize will be elicited differentially depending on the combination of job characteristics described above. We focus on abilities that have been shown to be related to outstanding executive performance in general. At the same time, we sought characteristics fine-grained enough in their definitions and measurements that they would be likely to show differences in outstanding performers in different executive roles. Although there are numerous abilities that could fit these criteria, we chose to use the leadership competencies identified by Boyatzis (1982) and further refined by Spencer and Spencer (1993). We draw on an archival database of this set of competencies. A large number of individual executive assessments against these competencies were available, along with associated data on the executives’ jobs and the adequacy of their performance. Competencies represent abilities and personal characteristics that are relatively enduring, “an underlying characteristic of an individual which is causally related to effective or superior performance in a job (Briscoe & Hall, 1999, p. 37).” Spencer and Spencer (1993) identified levels of sophistication or intensity for each competency they identified and McClelland (1998) Understanding Executive Jobs 12 showed that these competency levels are indeed associated with performance of executives in general. Throughout this paper, when competencies from Spencer and Spencer are used, they will be indicated by italics and capitalization to indicate that the Spencer and Spencer definitions of these characteristics and their levels of sophistication are being used. Study Hypotheses To this point we have identified a set of job characteristics and competencies that allow for a demands-abilities assessment when matching executives to their jobs. In this section we identify specific hypotheses that link the job characteristics and competencies. Competencies expected to vary with accountability for organizational results. Accountability for organizational results increases with the degree of direct control the executive has on organizational outcomes (Bellak, 1984). Thus, although an executive in a support role affects the ability of others to achieve results, his or her job is not rated as high in accountability for organizational results as an executive directly responsible for bottom-line results. When executives are more directly accountable for organizational results they must be constantly looking for new ways to improve performance, set standards, and measure them (Boyatzis, 1982; Ulrich et al., 1999). Thus, one competency that we expect to be associated with the increased accountability for organizational results is Achievement Orientation, which is defined as the sophistication and completeness with which one thinks about meeting and/or surpassing performance standards. This includes a concern for surpassing a standard of excellence. The standard may be one’s own past performance (striving for improvement); an objective measure (results orientation); outperforming others (competitiveness); challenging goals one has set, or even what anyone has ever done (innovation) (Spencer & Spencer, 1993). Although all executives need a baseline level of achievement orientation, as evidenced by its relation to Understanding Executive Jobs 13 management performance in general (Boyatzis; McClelland, 1998), we expect that as accountability for the organization’s financial results increases, outstanding performance will require greater levels of Achievement Orientation. Thus we hypothesize: H1: The level of Achievement Orientation demonstrated by outstanding executives will increase with jobs that are characterized by greater degrees of accountability for the organization’s financial results. As accountability increases, executives generally have larger groups of people reporting to them, (Bellak, 1984), and therefore must be more adept at achieving those results through other people. This means an executive must be able to clearly set a vision and goals, motivate the team, and generally provide high levels of “Team Leadership” (Spencer & Spencer, 1993; Tjosvold & Tjosvold, 1991). The competency Team Leadership is defined as the “strength and completeness with which the person assumes the role of leader.” This involves the intention to take a role as leader of a unit, and a desire to lead others. The “team” in the definition of this competency is understood broadly as any group in which the person takes on a leadership role, including the enterprise as a whole (Spencer & Spencer). Thus we hypothesize: H2: The level of Team Leadership demonstrated by outstanding executives will increase with jobs that are characterized by greater degrees of accountability for the organization’s financial results. Competencies expected to vary with complexity of problem solving. As an executive’s job becomes more complex, i.e., larger in size and with a greater focus on solving complex problems, we would expect the role demands to change. Complex problems require the application of knowledge in new and creative ways and the use of metaphor and analogy to apply knowledge to new situations (Mumford et al., 2000). Additionally, the complexity of the Understanding Executive Jobs 14 problem solving aspect of an executive’s job increases as executives move from implementing strategy to developing it. As an executive becomes more responsible for developing strategy, he or she must have an increasing ability to scan the business environment, understand the patterns unfolding (Porter, 1980, 1991) and attach meaning to them (Smircich & Stubbart, 1985). The ability to quickly see patterns in a rapidly unfolding situation and apply knowledge in new and creative ways requires the Conceptual Thinking competency. Conceptual Thinking is defined as insightfulness or innovation in pattern recognition. This competency involves the ability to identify patterns or connections between situations that are not obviously related, and to identify key or underlying issues in complex situations. It includes using creative, conceptual, or inductive reasoning (Spencer & Spencer, 1993). Thus we hypothesize: H3: The level of Conceptual Thinking demonstrated by outstanding executives will increase with jobs that are characterized by greater degrees of complexity in problem solving. As the complexity of problems to be solved increases, executives must also shift from short-term tactical thinking to long-term strategic thinking (Kovach, 1986). Whereas implementing organizational strategy requires a moderate ability to look into the future and plan ahead, formulating organizational strategy requires a much longer time horizon. The ability to look further into the future is captured in the competency Initiative (Spencer & Spencer, 1993). The competency labeled “Initiative” refers to the distance into the future that one identifies problems and opportunities on which to take action. This competency involves identification of a problem, obstacle, or opportunity and taking action to address current or future problems or opportunities. Initiative involves proactively doing things and not simply thinking about future actions. The time frame of the Initiative scale moves from addressing current situations to acting on future opportunities or problems as the level of this competency increases (Spencer & Understanding Executive Jobs 15 Spencer). At the highest level of this competency the executive is looking over a year into the future. Thus, we hypothesize: H4: The level of Initiative demonstrated by outstanding executives will increase with jobs that are characterized by greater degrees of complexity in problem solving. Increasing complexity of problems not only requires an executive to think farther into the future, it also requires the executive to more fully understand the organization and its relationship to the business environment (Mumford et al., 2000). An executive must be able to envision the effect of his or her solution on the various constituencies in the organization as well as on the future market position of the company (Mumford et al.). The competency “Organizational Awareness” is an ability to understand the organization and its relation to the environment. It is defined as thoroughness of understanding the power relationships in one’s own organization or in other organizations (customers, suppliers, etc.). This includes the ability to identify who the real decision makers are; the individuals who can influence them; and to predict how new events or situations will affect individuals and groups within the organization, and the organization’s relation to the business environment. Thus, we hypothesize: H5: The level of Organizational Awareness demonstrated by outstanding executives will increase with jobs that are characterized by greater degrees of complexity in problem solving. METHODS Sample Our sample includes 360 executives, i.e., those who manage middle managers, (257 males, 74 females, 29 not recorded) who participated in executive assessments for their organization. Participants were from 42 organizations in 12 industries representing a relatively balanced sample of companies and industries (see Table 1). The sample includes executives from Understanding Executive Jobs 16 7 geographical regions. Most were located in North America (47%), 8% were from Europe, 6% from Asia, and smaller percentages from the Mid-East, Africa, Australia and South America (see Table 2). ----------------------------------------------Insert Table 1 and Table 2 about here ----------------------------------------------Identifying Outstanding Performers “Outstanding performers” were those nominated by at least two people, typically 4 to 5, as being in the top 10% of executives in their company. Raters included executives more senior to the participant and Human Resources professionals who used criteria that are valued and commonly used in the organization to determine pay and promotions. Information from performance appraisals and objective measures appropriate to the position and organization, e.g., profitability, organizational climate, turnover, etc. were included in the nomination process. Researchers acted as sounding boards to ensure that the organization’s raters used the most appropriate criteria and nominated executives who truly were fully accomplishing the requirements of their roles. This was a conservative measure of executive effectiveness in that we could be quite confident that the executives in this group were ‘outstanding’ in the role in which they were assessed, even though this method of controlling for less than satisfactory performance may have excluded some other executives who were also outstanding. Measures Executive roles. Executive roles were measured using the Guide Chart-Profile framework (Hay, 1958; Hay & Purves, 1954) presented in Figure 1. The Guide Chart-Profile framework is a method of job evaluation that has been used by more than 6000 organizations in Understanding Executive Jobs 17 45 countries. It is noted as one of the most popular job evaluation methods in HR textbooks and handbooks (e.g., Armstrong, 2006; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). This system uses the dimensions of accountability for organizational results and complexity of problem solving to categorize executive jobs into specific roles, (see Figure 1 for a depiction of this framework and the associated roles). Discrete roles are defined using the concept of just noticeable differences (Gengerelli, 1977; Globerson, 1977). In other words, a person evaluating the job cannot, in practice, discern differences in jobs on a continuous basis. Rather, there is an increment in each dimension that a person trained in the system can discern. Jobs scoring between increments are all placed in the same role. For the executive jobs we considered in this study the framework includes three discrete categories of jobs along the accountability for results dimension and five categories of jobs along the complexity in problem solving dimension. The categories for each dimension are defined in more detail below. ---------------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here ---------------------------------Accountability dimension. For executive jobs, the dimension of accountability leads to one of three broad role profiles depending on the degree of accountability for business results. At one end of the spectrum are those executive roles that are held directly accountable for bottom-line results with control of the resources and decisions that directly impact financial results. A role in which one can reduce or increase production, invest in more efficient means of production, raise or lower prices, etc. allows for, and is held ‘accountable’ for a direct impact on profit and loss. These roles, commonly called “operational” or “line” roles, are considered to be high in accountability for profit and loss. At the other end of the spectrum are those executive Understanding Executive Jobs 18 roles that have only an indirect impact on financial measures, and where the desired outcomes are advice, counsel, and execution of support functions, e.g., HR, legal, and in some cases IT. These are “advisory” or “staff” roles, in which the executive rarely, if ever, has the opportunity to have a direct impact on profitability. In-between are increasingly popular “matrix” or “collaborative” roles (e.g., Ford & Randolph, 1992), where the executive is held partially accountable for financial results, but does not directly control many (or in some cases, any) of the necessary resources. These roles require coordination with other executives and some form of shared accountability. Complexity dimension. The second dimension, the complexity of an executive’s job, is associated with how much input the role has to the development of strategy, which is related to the degree and complexity of problem-solving and ultimately to the overall size of the job. For example, in entry-level positions the focus is mainly on technical expertise rather than problemsolving. As jobs become more strategic, the focus shifts to problem-solving, more than the simple utilization of technical expertise to achieve results. In entry-level jobs technical expertise may account for 70% of job content while at the CEO level it may be as little as 30%. It is not that the actual technical expertise decreases, but rather that the proportional need for problemsolving increases. The framework divides jobs into five discrete roles based on just noticeable differences in this dimension. At the lowest level of complexity are jobs that involve implementation of organizational or departmental strategies. At the higher levels are roles that involve aligning and formulating strategy. Identifying executive roles. The jobs of the executives interviewed in this study included all three role types along the accountability for results dimension and four role types Understanding Executive Jobs 19 along the complexity for problem solving dimension. (Note: the enterprise leadership level of complexity was not represented in this study due to lack of sufficient data for this level.) The classification was done in multiple phases by three researchers trained in the Guide Chart-Profile job classification methodology. These researchers were rigorously trained and accredited by experts in the methodology to maintain at least 75% inter-rater reliability. The distribution of jobs in this sample is presented in Table 3. -------------------------------Insert Table 3 about here -------------------------------Executive competencies. Each subject in the database participated in a Behavioral Event Interview (BEI) (McClelland, 1998), which is a form of the critical incident interview technique (Flanagan, 1954). Interviewees are asked to alternately describe situations where they felt particularly effective and where they felt they could have performed better. Events are required to have occurred within approximately the past year and a very high level of detail is sought in the interview, both of these requirements contribute to the reliability and validity of the interview for obtaining accurate descriptions of work behavior (Motowidlo et al., 1992; Ronan & Latham, 1974). The executive BEIs lasted an average of 3-4 hours and typically cover three events. Interviewers completed a three-day training program and are only accredited to conduct BEIs if they maintain a minimum 75% inter-rater reliability. The interviewers, who are blind to the performance rating of the interviewee, insure that descriptions provide codeable data by asking non-leading questions such as, "What led up to the event?" "Who did and said what to Understanding Executive Jobs 20 whom?" "What happened next?" "What were you thinking or feeling at that moment?" and "What was the outcome?" The interviews were transcribed and coded according to a detailed codebook that includes behavioral descriptions and examples of each level of each competency and coding rules required to maintain reliability. Each competency is defined using specific behaviors and thoughts that are ordered by levels of complexity or scope as defined by Spencer and Spencer (1993) (see Table 4 for definitions of the competencies used in this study). -------------------------------Insert Table 4 about here -------------------------------To code a behavior it must be clearly described as (1) having been explicitly done (said, thought or felt) by the interviewee (i.e., not statements that use the term “we” did something or where the action is unclear); (2) as having taken place in the course of this specific recent event (i.e., nothing that the person plans to do, or “usually does” or thinks they should or might do); and (3) with convincing detail as to how it was accomplished (i.e., “I presented a business case to Joe. I showed him the costs and benefits of purchasing the new machine;” rather than “I convinced Joe to buy the machine.”). Because of the strict rules for coding competencies, the BEI provides a conservative measure of competencies demonstrated by the interviewee. Behaviors not described fully and explicitly are not coded (McClelland, 1998), thus only competencies for which there is very clear evidence are coded. For each executive in this study, individual competencies were measured by the highest level demonstrated in the interview. When coding the competencies we assume that all executives had a fair opportunity to display any and all of the competencies used in this study Understanding Executive Jobs 21 during their three to four hour interview. Thus, if a competency was not evident in the transcript of an executive’s interview, it was assigned a level zero. RESULTS Table 5 shows descriptive statistics and correlations among the competencies coded. All hypotheses were tested using a two-way ANOVA that included both the accountability for organizational results and complexity of problem solving characteristics of the job as factors. This analytic choice provides a conservative estimate of the effects of a given factor on the competency levels displayed by outstanding executives because the effect is only significant if it contributes uniquely to the variance explained. Because we want to test whether or not the competency level displayed by outstanding executives increases with increasing accountability for organizational results or increasing complexity in problem solving we also performed planned polynomial contrasts on each factor. The linear component of the contrast analyses examines the trends in the effects. Since we hypothesize that the level of a competency displayed by outstanding executives will increase as accountability for organizational results or complexity of problem solving increases, we expect the linear component of the polynomial contrast to be significant. To determine whether or not the slope is positive or negative we need to examine the mean levels of a competency for each level of the factor. Table 6 shows the results of the ANOVA analysis and Table 7 shows the estimated marginal means for each level of each factor. --------------------------------------------------------Insert Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7 about here --------------------------------------------------------- Understanding Executive Jobs 22 Hypotheses 1 and 2 state, respectively, that the level of Achievement Orientation and Team Leadership demonstrated by outstanding performing executives will increase with jobs that are characterized by greater degrees of accountability for organizational results. Hypotheses 1 (Achievement Orientation) and 2 (Team Leadership) are both supported. For both of these competencies the effect of the accountability for organizational results factor is significant as is the linear component of the polynomial contrast. An examination of the means shows that they increase as accountability for organizational results increases, i.e., as we move from advisory to operational roles. Hypotheses 3 through 5 state, respectively, that the level of Conceptual Thinking, Initiative, and Organizational Awareness demonstrated by outstanding executives will increase with jobs that are characterized by greater degrees of complexity in problem solving. These hypotheses are also supported. The effect of the complexity of problem solving factor is significant as is the linear component of the polynomial contrast. An examination of the means shows that the mean levels of the competencies generally increase with increasing levels of complexity in problem solving. However, at the strategy formation level the means for Conceptual Thinking and Organizational Awareness dip slightly below the strategic alignment level of complexity in problem solving. Nevertheless, the overall trend is positive. DISCUSSION Finding the right executive for a job is more difficult and more critical today than ever. Organizations spend millions on assessments, talent planning, and leadership development, yet executives often fail in new roles. The research presented here examines this issue from the perspective of Person-Job fit. At the executive level, matching an executive to the job has often been done without examining the specific characteristics of the job. For example, organizations Understanding Executive Jobs 23 look for good leaders because an executive position is one of leadership. They look for executives who have experience with strategies similar to that which they will be asked to implement. And sometimes, people trying to match an executive to a job fall into the trap of assuming that jobs with similar titles make similar demands on an executive. The findings of our study show that examining specific characteristics of the executive job can improve our ability to understand the competencies that the role demands. Specifically, we find that outstanding executives across a variety of industries and geographic regions demonstrate increasing levels of Achievement Orientation and Team Leadership as the degree of accountability for organizational results characteristic of their jobs increases. We also found that outstanding executives demonstrate increasing levels of Conceptual Thinking, Initiative, and Organizational Awareness as degrees of complexity in problem solving characteristic of their jobs increases. Understanding Executive Roles The ability to analyze an executive’s job in a way that is independent of job titles and the organization is important for executive placement given that organizational models are moving away from traditional hierarchy (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1993). Globalization, technology development, and the ever changing business environment are challenging the authority-based hierarchy in traditional organizations (Kickul & Gundry, 2001). Executive roles are less defined by titles and behaviors, and more by a set of responsibilities and by contribution to business strategy (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1997; Hambrick, Finkelstein & Mooney, 2005). Using the job characteristics of accountability for organizational results and complexity of problem solving fills a gap in our understanding of the demands that different executive jobs place on individuals to perform them effectively. Analyzing an executive job this way allows us to more accurately compare roles across organizations. This means of understanding the executive job is not so Understanding Executive Jobs 24 specific that it applies only to one job, nor is it so broad that it treats all leaders similarly. Using job characteristics applicable to all jobs avoids the limitation of using sometimes misleading job titles to compare executive jobs. It allows us to more accurately predict changes in job demands when an executive changes roles or organizations. Although this study does not intend to provide a complete list of competencies specific to each role, it finds evidence that different executive roles call upon different competencies. Although the competencies used in this study have been shown to be related to executive performance in general (Boyatzis, 1982; McClelland, 1998; Spencer & Spencer, 1993), this study shows that outstanding executives are not homogenous in their competencies. Executive job differences require that individuals use different competencies depending on their specific role. The findings of this study also provide some insight into the scope of executive jobs for which the competencies are applicable. The competencies of Achievement Orientation and Team Leadership are found to be associated with accountability for results as hypothesized but they were also associated with complexity of problem solving (based on the linear contrast). This makes sense because as jobs become more complex we would expect that executives who set and meet high standards, bring in diverse perspectives, and help create meaning, would perform better. An important implication is that as executives move from one role to another in the framework presented in Figure 1, it is critically important to understand the changes in competencies required to perform the job. If one increases accountability for results at the same time as increasing complexity, then the change in job demands for Team Leadership, and to a lesser extent Achievement Orientation, will be potentially large. Thus, one might consider these to be more fundamental competencies. Understanding Executive Jobs 25 Similarly, the competency of Initiative was found to be related to complexity of problem solving as hypothesized but it is also related to the degree of accountability. The linear contrast, however, is not significant. An examination of the means shows that the average level of this competency increases by .15 going from advisory to collaborative roles but increases by more than three times that (.49) going from collaborative to operational roles, indicating that a shift to operational roles may be much more demanding with respect to this competency than a shift from an advisory role to a collaborative role. This makes sense as the more accountable you are for results the further you need to look ahead and anticipate opportunities and threats. This information, once again, can be very useful when planning changes in executive roles. An executive with a medium level of Initiative may be fine when going from an advisory role to a collaborative role but be stretched if moved into an operational role. If at the same time the executive is given a promotion to a job higher in complexity, the latter change might result in failure whereas the former may not. Implications for Practice Although this study was not intended to provide a prescriptive guideline for executive placement practices, it sheds light on several aspects of executive placement. This study highlights the importance of understanding role requirements when selecting executives. Aside from matching an executive’s abilities to the contextual and technical demands of the job, role demands are found to have a direct effect on the competencies demonstrated by high-performing executives. This finding has implications for executive selection, development, performance management, and succession planning. With an understanding of the difference between executive roles and the competencies associated with different role profiles, organizations can assess, select, and develop managers with greater precision. Understanding Executive Jobs 26 The most obvious implication is for executive selection. Understanding the job in terms of its characteristics can add to an organization’s ability to match an executive to a job. Not only can a better match be made but understanding the competencies required for success in a specific job provides a more practical means of selecting executives for the job as compared to the alternative of selecting for all competencies and ignoring the characteristics of the job. Findings from this study also have implications for succession planning, especially the ways in which the nature of a job changes as the executive is transferred or promoted. Executive roles can be understood by defining them on the dimensions of complexity of problem solving and accountability for organizational results. Moving along either dimension creates a change in the nature of the role. When an executive moves from one position to another, it behooves an organization to evaluate how much “stretch” the move creates for the person. Does it require a different set of competencies? A move along both dimensions at once is likely to be extremely difficult given the degree of shift in competency requirements. When conducting succession planning, any organization must consider how many moves are realistic to prepare high potentials for senior level positions. Clarity on the role differences and associated competencies helps companies systematically develop organizational bench strength while reducing the likelihood of failure because a move requires too many new competencies. This study also has implications for performance management of executives. The problem of increasing ‘managerial effectiveness’ would be informed by further consideration of the executive competencies that are appropriate for achieving specific outcomes. The framework presented and tested in this study is a first step to understanding how to differentiate among executive jobs and identify competencies associated with specific roles. Linking roles with Understanding Executive Jobs 27 necessary competencies provides the foundation for agreeing on individual objectives and formulating personal developmental plans. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research While this study improves our understanding of executive roles, it has limitations. The study cannot directly address the question of the degree of association between various competencies and executive performance, even though we studied people who were rated as high-performing. The focus of our study was to test the empirical relationship between specific characteristics of executive roles and the competencies demonstrated by people fulfilling those roles. It establishes accountability for organizational results and complexity of problem solving as factors that explain some of the variance in executive competencies, but it does not generate a complete list of competencies that are associated with performance differences in the role. To differentiate executive performance, further research can expand on this study by studying a group of executives across the accountability and problem solving dimensions who vary widely in performance. Comparisons among the executives in each role profile would then be able to identify a set of executive competencies that differentiate performance for each role. Further, previous research on competencies has pointed out that a worker’s way of framing and experiencing the work may be a competency in and of itself (Sandberg, 2000). Although our study took a rationalistic approach to define and examine executive jobs separately from people in the role, we acknowledge the interaction between individual executives and how their roles are actually carried out. It is understood that jobs are subject to the interpretation of the job holders, and it should not be assumed that executives understand the nature of their jobs the same way we define roles in this study. Understanding Executive Jobs 28 Nevertheless, executive jobs do vary in objective characteristics. After all, organizations hold executives accountable for producing the results their roles exist to deliver. Defining the role based on the specific job characteristics provides an objective framework for executives to align their behaviors accordingly. That being said, future research can help create such alignment by using the job dimensions of accountability for organizational results and complexity of problem solving to look into the relationship between the objective nature of roles and executives’ interpretation of the roles. Empirical findings regarding the specific competencies associated with different managerial roles not only contribute to our understanding of these roles, but also open new questions on the emerging executive roles. More and more organizations have matrix structures (Atkinson, 2003; Burns & Wholey, 1993). Collaborative executive roles as defined by midrange degrees of accountability for organizational results are found to be increasing in numbers. Given the renaissance in matrix organizations (Atkinson; Numerof & Abrams, 2002) and the increasing demand for executives to take on collaborative roles, more research is needed to identify competencies associated with such roles. It is possible that the set of competencies we used were not sufficient to understand the unique requirements of the executive role in a matrix organizational structure. Conclusion This paper fills a gap in our understanding of how to match an executive to his or her job by using the lens of a demands-abilities, Person-Job fit. We provide a conceptual framework to define executive roles using the dimensions of accountability for results and complexity of problem solving and empirically show that outstanding executives display different competencies as the characteristics of their jobs change along these dimensions. The Understanding Executive Jobs 29 accountability for organizational results and complexity of problem solving characteristic of executive roles have each been found to have a main effect on the competencies demonstrated by outstanding managers. Results from the findings have implications for organizational role requirement clarification, selection, assessment, and development of managers. It also opens directions for future research to advance our understanding of executive roles and how those roles affect the fit between the demands of the role and the competencies of the executive. Understanding Executive Jobs 30 REFERENCES Armstrong, M. 2006. A handbook of human resource management practice (10th ed.). Landon and Philadelphia: Cogan Page. Atkinson, P. 2003. Managing chaos in a matrix world. Management Services, 47(11): 8-11. Barrington, L., & Silvert, H. 2004. CEO challenge 2004: Top 10 challenges. New York: The Conference Board Inc. Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. 1993. Beyond the m-form: Toward a managerial theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 14(Winter): 23-46. Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. 1997. The myth of the generic manager: New personal competencies for new management roles. California Management Review, 40(1): 92-116. Bassett, G. A. 1969. The qualifications of a manager. Harvard Business Review, 12(2): 35-44. Beal, R. M., & Yasai-Ardekani, M. 2000. Performance implications of aligning CEO functional experiences with competitive strategies. Journal of Management, 26(4): 733-762. Bellak, A. O. 1984. Specific job evaluation systems: The Hay Guide Chart-Profile method. In M. L. Rock (Ed.), Handbook of wage and salary administration: 15/11 to 15/16: McGraw-Hill Education. Blair, E. H. 1999. Which competencies are most important for safety managers. Professional Safety, 44(1): 28-32. Boyatzis, R. 1982. The competent manager: A model for effective performance. New York: John Wiley. Briscoe, J. P., & Hall, D. T. 1999. Grooming and picking leaders using competency frameworks: Do they work? Organizational Dynamics, Autumn: 37-51. Browne, P. J., & Golembiewski, R. T. 1974. The line-staff concept revisited: An empirical study of organizational images. The Academy of Management Journal, 17(3): 406-417. Burns, L. R., & Wholey, D. R. 1993. Adoption and abandonment of matrix management programs: Effects of organizational characteristics and interorganizational networks. Academy of Management Journal, 36(1): 106-138. Castanias, R. P., & Helfat, C. E. 1991. Managerial resources and rents. Journal of Management, 17(1): 155-171. Church, A. H., & Waclawski, J. 2001. Hold the line: An examination of line vs. Staff differences. Human Resource Management, 40(1): 21-34. Understanding Executive Jobs 31 Conger, J. A., & Nadler, D. A. 2004. When CEOs step up to fail. MIT Sloan Management Review, Spring: 50-56. Dainty, A. R. J., & Cheng, M. I. 2005. Competency-based model for predicting construction project managers’ performance. Journal of Management in Engineering, 21(1): 2-9. Dess, G. G., & Picken, J. C. 2000. Changing roles: Leadership in the 21st century. Organizational Dynamics(Winter): 18-33. Drazin, R., & Rao, H. 1999. Managerial power and succession: SBU managers of mutual funds. Organization Studies, 20(2): 167-196. Economist. 2003a. Coming and going. Economist: 12, 13p. Economist. 2003b. Making companies work. Economist: 14, 12p. Fernandez-Araoz, C. 1999. Hiring without firing. Harvard Business Review, 77(4): 109-120. Fernandez-Araoz, C. 2005. Getting the right people at the top. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46(4): 67-72. Finkelstein, S., & Hambrick, D. C. 1996. Strategic leadership: Top executives and their effects on organizations. Minneapolis/St. Paul: West Publishing Company. Flanagan, J. C. 1954. The critical incident technique. Psychology Bulletin, 51: 327-358. Ford, R. C., & Randolph, W. A. 1992. Cross-functional structures: A review and integration of matrix organization and project management. Journal of Management, 18(2): 267-294. Galbraith, J. R. 1977. Organization design: Addison-Wesley Reading, Mass. Gengerelli, J. A. 1977. A quantum treatment of the psychophysical law. Journal of Psychology, 97: 231-236. Gerdes, L. 2007. Hello, goodbye. Businessweek, 1/22: 16. Globerson, S. 1977. The just noticeable difference in complexity of jobs. Management Science, 23(6): 606-611. Gomez-Mejia, L., Balkin, D., & Cardy, R. 2007. Managing human resources (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. 1984. Business unit strategy, managerial characteristics, and business unit effectiveness at strategy implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 27(1): 25-41. Guthrie, J. P., & Datta, D. K. 1997. Contextual influences on executive selection: Firm characteristics and CEO experience. Journal of Management Studies, 34(4): 537-560. Understanding Executive Jobs 32 Hall, D. T., & Moss, J. E. 1998. The new protean career contract: Helping organizations and employees adapt. Organizational Dynamics, 26(3): 22-37. Hambrick, D. C., Finkelstein, S., & Mooney, A. C. 2005. Executive job demands: New insights for explaining strategic decisions and leader behaviors. Academy of Management Review, 30(3): 472-491. Hay, E. N. 1958. Any job can be measured by its "know, think, do" elements. Personnel Journal, 36(11): 403-406. Hay, E. N., & Purves, D. 1954. A new method of job evaluation: The Guide Chart-Profile method. Personnel, July: 72-80. Hayes, J., Rose-Quirie, A., & Allinson, C. W. 2000. Senior manager's perceptions of the comptencies they require for effective performance: Implications for training and development. Personnel Review, 29(1): 92-105. Horch, H. D. 2003. Competencies of sport managers in German sport clubs and sport. Managing Leisure, 8(2): 70-84. Jordan, M. H., & Schraeder, M. 2003. Executive selection in a government agency: An analysis of the department of the navy's senior executive service selection process. Public Personnel Management, 32(3): 355-366. Kickul, J., & Gundry, L. 2001. Breaking through boundaries for organizational innovation: New managerial roles and practices in e-commerce firms. Journal of Management, 27(3): 347361. Kovach, B. E. 1986. The derailment of fast-track managers. Organizational Dynamics, 15(2): 41-48. Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. 2005. Consequences of individuals' fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2): 281-342. Kristof, A. L. 1996. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49(1): 1-49. McClelland, D. C. 1998. Identifying competencies with behavioral-event interviews. Psychological Science, 9(5): 331-339. Mogel, G. S. 2006. Top-executive turnover set record in January: Officer changes may be investment red flag. Investment News, 10(7): 30. Motowidlo, S. J., Carter, G. W., Dunnette, M. D., Tippins, N., Werner, S., Burnett, J. R., & Vaughan, M. J. 1992. Studies of the structured behavioral interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77: 571-587. Understanding Executive Jobs 33 Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleishman, E. A. 2000. Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. Leadership Quarterly, 11(1): 11-35. Numerof, R. E., & Abrams, M. N. 2002. Matrix management: Recipe for chaos? Directors & Boards, 26(4): 42-46. O'Roark, A. M. 2002. The quest for executive effectiveness: Consultants bridge the gap between psychological research and organizational application. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 54(1): 44-54. Pavett, C. M., & Lau, A. W. 1983. Managerial work: The influence of hierarchical level and functional specialty. Academy of Management Journal, 26(1): 170-177. Pfeffer, J. 1977. Toward an examination of stratification in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(4): 553-567. Pomeroy, A. 2005. Take this executive job and. HR Magazine, 50(5): 14. Porter, M. E. 1980. Competitive strategy. New York: Free Press. Porter, M. E. 1991. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 12(Winter): 95-117. Raelin, J. A. 1997. Executive professionalization and executive selection. Human Resource Planning, 20(2): 16-27. Ronan, W. W., & Latham, G. P. 1974. The reliability and validity of the critical incident technique: A closer look. Studies in Personnel Psychology, 6: 53-64. Sandberg, J. 2000. Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43(1): 9-25. Skenes, C., & Kleiner, B. H. 2003. The Hay system of compensation. Management Research Review, 26(2-4): 109-115. Smircich, L., & Stubbart, C. 1985. Strategic management in an enacted world. Academy of Management Review, 10(4): 724-736. Spencer, L. M., & Spencer, S. M. 1993. Competence at work: Models for superior performance. New York: John Wiley & Sons. Thomas, A. S., & Ramaswamy, K. 1996. Matching managers to strategy: Further tests of the miles and snow typology. British Journal of Management, 7: 247-261. Tjosvold, D., & Tjosvold, M. M. 1991. Leading the team organization: How to create an enduring competitive advantage. New York: MacMillan. Understanding Executive Jobs 34 U.S. Department of Labor. 1991. Dictionary of occupational titles (4th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Ulrich, D., Zenger, J., & Smallwood, N. 1999. Results-based leadership: How leaders build the business and build the bottom line. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press. Understanding Executive Jobs TABLE 1 Distribution of Sample by Industry Industry # Cases Percent Manufacturing 53 15% Food Products 51 13% Chemical and Pharmaceutical 46 13% Technology 62 16% Telecommunications 25 7% Financial Services and Banks 42 11% Insurance 21 6% Health 16 4% Petroleum 21 6% Retail 4 .5% Hospitality/Tourism 2 .5% Communications 11 3% Unknown 6 2% Total 360 35 Understanding Executive Jobs TABLE 2 Distribution of Sample by Geography Geographical Region # Cases Percent North America 171 47.5% Europe 28 7.8% Asia 21 5.8% South America 7 1.9% Africa 3 .8% Mid-East 4 1.1% Australia 4 1.1% Unknown 122 34% Total 360 36 Understanding Executive Jobs TABLE 3 Distribution of Executive Jobs by Role Profile and Job Complexity Role Profile Complexity Advisory Collaborative Operational Total Tactical Implementation 13 23 56 92 Strategic Implementation 19 32 54 105 Strategic Alignment 16 35 44 95 Strategy Formulation 0 12 56 68 Total 48 102 210 360 37 Understanding Executive Jobs 38 TABLE 4 Definition of Competencies used in this Study Competency Definition Sophistication and completeness with which one thinks about meeting and/or surpassing performance standards Achievement Orientation A concern for working well or for surpassing a standard of excellence. The standard may be one’s own past performance (striving for improvement); an objective measure (results orientation); outperforming others (competitiveness); challenging goals one has set, or even what anyone has ever done (innovation). Strength and completeness of assumption of the role of leader Team Leadership The intention to take a role as leader of a team or other group. It implies a desire to lead others. Team Leadership is generally, but certainly not always, shown from a position of formal authority. The “team” here should be understood broadly as any group in which the person takes on a leadership role, including the enterprise as a whole. Insightfulness or innovation of the pattern recognition Conceptual The ability to identify patterns or connections between situations that are not obviously Thinking related, and to identify key or underlying issues in complex situations. It includes using creative, conceptual, or inductive reasoning. The distance into the future that one is looking for problems and opportunities on which to take action Refers to the following: Initiative 1. The identification of a problem, obstacle, or opportunity and 2. Taking action in light of this identification to address current or future problems or opportunities. Initiative should be seen in the context of proactively doing things and not simply thinking about future actions. The time frame of this scale moves from addressing current situations to acting on future opportunities or problems. Thoroughness of understanding of one’s own or another’s organization The ability to understand and learn the power relationships in one’s own organization Organizational Awareness or in other organizations (customers, suppliers, etc.). This includes the ability to identify who the real decision makers are; the individuals who can influence them; and to predict how new events or situations will affect individuals and groups within the organization. Understanding Executive Jobs TABLE 5 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations (n = 360) Competency 1. Achievement Orientation Meana S.E.b 3.20 .10 1 2 3 2. Team Leadership 3.62 .12 0.28** 3. Conceptual Thinking 3.13 .08 0.18** 0.27** 4. Initiative 2.61 .10 0.45** 0.26** 0.32** 5. Organizational Awareness 3.39 .09 0.34** 0.31** ** p < .01 a Estimated Marginal Grand Mean b Standard Error 0.38** 4 0.36** 39 Understanding Executive Jobs 40 TABLE 6 Results of Two-way ANOVA by Competency ANOVA Linear Contrast Mean Adj Sq. F Sig. . R2 Est. Sig. Corrected Model 7.72 2.93 0.00 .05 -- -- Accountability 16.58 6.29 0.00 0.46 0.02 Complexity 5.30 2.01 0.11 0.56 0.01 Accountability * Complexity 1.55 0.59 0.71 -- -- Corrected Model 10.06 2.83 0.00 -- -- Accountability 14.03 3.95 0.02 0.61 0.01 Complexity 14.88 4.19 0.01 0.85 0.00 Accountability * Complexity 2.24 0.63 0.68 -- -- Corrected Model 4.35 2.24 0.01 -- -- Accountability 3.66 1.89 0.15 -0.17 0.29 Complexity 8.62 4.45 0.00 0.58 0.00 Accountability * Complexity 3.28 1.69 0.14 -- -- Corrected Model 11.22 4.26 0.00 -- -- Accountability 8.37 3.17 0.04 0.26 0.17 Complexity 10.15 3.85 0.01 0.85 0.00 Accountability * Complexity 6.17 2.34 0.04 -- -- Corrected Model 8.21 3.72 0.00 -- -- Organizational Accountability 5.19 2.35 0.10 0.18 0.32 Awareness (H5) Complexity 17.79 8.07 0.00 0.48 0.02 Accountability * Complexity 6.39 2.90 0.01 -- -- Competency Achievement Orientation (H1) Team Leadership (H2) Conceptual Thinking (H3) Initiative (H4) Source .05 .03 .08 .07 Note: Dashes indicate analysis of linear effects for these sources of variance is inappropriate. Degrees of freedom for the corrected model = 10, accountability = 2, complexity = 3, the accountability by complexity interaction = 5, error = 349, and the corrected total = 359. Understanding Executive Jobs 41 TABLE 7 Estimated Marginal Means Role Profile Advisory Achievement Orientation Team Leadership Conceptual Thinking Initiative Organizational Awareness a Standard Error Tactical Strategic Strategic Strategy Implementation Implementation Alignment Formation Operational Meana S.E.b Meana S.E.b Meana S.E.b Meana S.E.b Meana S.E.b Meana S.E.b Meana S.E.b 2.86 0.24 3.00 0.18 3.66 0.11 2.85 0.20 3.08 0.17 3.35 0.18 3.68 0.26 3.07 0.28 3.60 0.20 4.07 0.13 3.01 0.23 3.51 0.20 3.80 0.21 4.45 0.30 3.38 0.20 2.99 0.15 3.08 0.10 2.69 0.17 3.10 0.15 3.48 0.16 3.29 0.22 2.32 0.24 2.47 0.18 2.96 0.11 2.22 0.20 2.44 0.17 2.69 0.18 3.33 0.26 3.26 0.22 3.24 0.16 3.64 0.10 2.67 0.18 3.45 0.16 3.81 0.17 3.77 0.24 Estimated Marginal Mean b Collaborative Complexity Understanding Executive Jobs 42 FIGURE 1 Guide Chart-Profile Framework ROLE PROFILE Enterprise Leadership JOB COMPLEXITY Strategic Alignment Strategic Implementation Tactical Increasingly Complex Problem-Solving Strategic Strategy Formation Tactical Implementation Advisory Roles Collaborative Roles Operational Roles NA NA Leads all aspects of business to generate results. Typically the highest level leadership role in a diverse enterprise with multiple business units, lines, and markets. Focuses on the alignment and integration of strategies for a function that is a critical driver of business success. Partners in determining business strategy and provides strategic advice that supports the achievement of critical business objectives. Develops and delivers strategically important programs critical to the organization’s mission through coordination and direction of diverse resources over whom direct control is not exercised. Focused on the achievement of bottom-line results where global and / or business-critical objectives must be achieved. Typically more complex general manager or sales roles. Focuses on the alignment and integration of policy in a strategically important and diverse area. Provides advice and guidance that support the achievement of major business objectives. Seen as thought leader internally. Defines and delivers specific and measurable long-term programs and results through a complex network of resources and partners over whom direct control is not exercised. Focuses on the achievement of bottom-line results where product and market developments demand significant change to current business capabilities. Typically general manager or sales roles. Focuses on the translation and application of policy in diverse although usually related areas. Delivers specific, measurable results across a broad, complex area through a network of diverse resources and partners over whom direct control is not exercised. Integrates and balances operational or sales resources to extend current business capabilities, ensuring that market demands are met in the short and medium term. Focuses on the translation and application of policy in a specific functional area. Delivers specific, measurable results in a discrete, defined area through a network of internal and external resources and partners over whom direct control is not exercised. Manages a large, complex operating unit to predetermined requirements. Manages defined resources to ensure achievement of clearly specified objectives such as volume, cost, quality, and service to meet schedule and customer requirements. Increasing Accountability for Organizational Results