Gold and Diamonds: The Social and Environmental Impacts of

advertisement

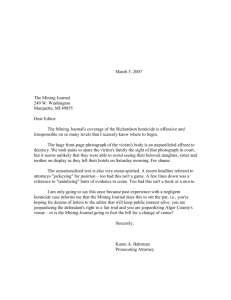

Gold and Diamonds: The Social and Environmental Impacts of Mining for the Diamond Ring MPA Conference 2007 Katharina Marcin Nicholas Ruder Table of Contents Introduction 2 Life Cycle Assessment 3 Major Environmental Impact Summary 7 Mining Sustainability Initiatives 7 Canadian Policies and Regulations 11 Cases: Leaders and Laggards in the Mining Industry 13 The Canadian Mining Experience 17 Major Stakeholders 20 Recommendations 23 Eliminating Mining from the Life Cycle: Golden Circle Jewellers 24 Conclusion 26 References 27 Appendices Appendix A 31 Appendix B 32 1 Gold and Diamonds: The Social and Environmental Impacts of Mining for the Diamond Ring Introduction In order to explore the mining industry in Canada from a perspective that affects us through a symbol of love, unity, and value, the diamond engagement ring has been chosen as the example of how our desires affect the social and natural environment of mines around the world, as well as in Canada. The diamond engagement ring is not necessary to our survival; we do not depend on it for transportation, better lifestyles, electricity, or any other necessity. The diamond ring is a purely superficial object that our society values enormously thanks to very effective marketing campaigns. Given the high social and environmental impact of gold and diamond mining on millions of peoples’ lives around the world, it is important to start questioning the importance of “bling,” and whether diamonds really are a girl’s best friend. The gold and diamond industry is an important economic resource for many countries. Most gold mined is converted into jewellery which has been highly valued for over 8000 years. The second largest market for gold is the electronics industry, because gold does not easily corrode, and is highly conductive. This industry accounts for 8 percent of global demand for gold.1 Most gold mines (90 percent) in Canada are openpit, and hard-rock underground operations. In terms of gold production, Canada is ranked eighth in the world, and exports $3.6 Billion a year. Canadian mine production has decreased in the last several years, but world demand continues to creep up. The rise in gold price has not affected Canadian producers as much as can be expected in 2005, because of the high Canadian dollar, and higher energy costs associated with mining operations.2 The diamond industry in Canada is currently worth $2 Billion.3 The first Canadian diamond mine is the Ekati mine in the Northwest Territories. The second is Diavik, which produces more than Ekati. Three other mines are set to open in the near future in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, which will rank Canada third in world diamond production after Botswana and Russia.4 Mining operations are not the only source of employment in Canada from the diamond industry; new cutting and polishing facilities have opened up north, in addition to pre-existing facilities in southern Canada. The Canadian diamond industry currently employs 4000 people directly and indirectly, 40 percent of whom are Aboriginal at Ekati and Diavik.5 Currently Canada produces 15 percent of the world’s diamonds, but has 80 percent of the world’s “excellent” or “ideal cut” makes.6 Chevalier, P. Gold. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/ms/pdf/nfo/nfo05/gold_e.pdf Ibid. 3 Canada: A Diamond Producing Nation. NRCan. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/ms/diam/index_e.htm 4 Ibid. 5 Ibid. 6 Canadian Diamonds. Diamond Info. http://www.diamondinfo.org/canadian-diamonds.html 1 2 2 Life Cycle Assessment Components The major components that comprise a diamond ring are diamonds and gold. Lesser components that are present but in low and variable amounts are: copper, nickel, silver and zinc. All of these elements and the processes associated in their acquisition will be taken into consideration for this Life Cycle Assessment, which can be broken down into five broad stages: exploration, extraction, processing, manufacture and retail, use and re-use (See Appendix A). Phase 1: Exploration The exploration phase of the life cycle assessment is considered a preliminary phase of the mining process. A small fraction of exploration projects proceed to the extraction phase. For this reason exploration is rarely taken into consideration in a life cycle assessment of products in the mining industry. 7 The processes involved in exploration include: geological surveys, geophysical surveys, trenching and drilling. Geological surveys generally involve mapping, surveying and prospecting. The geophysical surveys can include airborne (helicopter and/or airplane) and ground surveys. The trenching process is the stripping of overburden with heavy equipment to expose underlying bedrock. Depending on remoteness of the area, road construction may be needed for access for drilling and trenching equipment. The exploration for metals and diamonds uses energy, water and land resources.8 The energy used to power equipment, electricity and fossil fuels varies with the type of process. Large amounts of fuel are used in the advanced stages of exploration to power equipment (e.g. generators, excavation equipment, helicopters, and airplanes). Water is used throughout this phase, most intensively in the trenching and drilling for washing and drilling fluid, respectively. Varying amounts of tree cutting and soil disturbance can be attributed to exploration activities, most notably the clearing of forest for roads and trails, and the stripping of soil and vegetation for trenching.9 Air emissions are a significant output for this phase of the life cycle. Helicopters, airplanes and heavy equipment consume large amounts of fuel and thus expel CO2 into the atmosphere. Trenching and drilling produce considerable amounts of waste soil, rock, and water. Land disturbance and water contamination are the biggest environmental concerns involved with mining exploration. The cutting of trees, stripping of soil can have serious implications for soil erosion, which can also lead to increased sediment in water bodies and may be harmful to fish and fish habitats10. Fluids and drill cuttings from the drilling process can also pose a risk to water systems if not disposed of properly. In more 7 Durucan et al. Mining life cycle modeling: a cradle-to-gate approach to environmental management in the minerals industry. Journal for Cleaner Production. 2006. 14;1057-1070. 8 Poliquin, Morgan. Mineral Exploration Techniques. Kitco Casey. 2005. http://www.kitcocasey.com/displayMining.php?id=5 9 Ibid. 10 Working on Crown Land: What you should know about Mineral Exploration, Building Construction and Road and Trail Construction. NRCan. 1996. http://www.mnr.gov.on.ca/MNR/csb/news/crown1.html 3 advanced exploration projects the amount of fuel and electricity used could be considered a major contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and global climate change. Phase 2: Extraction The extraction phase of the life cycle assessment encompasses all aspects of mining and extraction of raw minerals and metals. While mining is a large part of the Canadian economy, it has extensive environmental impacts that need to be considered. The extraction of raw materials is one of the biggest concerns for environmental impacts in the life cycle assessment of a diamond ring. Two main types of mining methods are the surface method, and the underground method. The former, is used when the deposit is located over a broad area close to the surface. The latter, is used when there is a high grade deposit over a smaller area deeper beneath the surface. Most of the world’s mines are open-pit mines, which are large craters blasted into mostly environmentally or historically protected areas.11 Open-pit mines generate large amounts of waste rock which has made groundwater thousands of times more acidic than battery acid. There are very large inputs involved in the mining process. Land resource use varies dependant on the method being used for extraction; surface mining covers a large land area and can cause extensive land disturbance due to removal of overburden (soil and surface rock) and vegetation. Water is used throughout this phase, most notably in separation and drilling. Surface and groundwater can be encountered throughout the mining process and needs to be diverted and disposed of due to its contamination. Very high amounts of fuel and electricity are consumed in powering equipment and transportation of personnel and materials. The main objective of extraction is the output of concentrated metals and diamonds. Other outputs that are involved include: air emissions, waste water and solid waste. According to Environment Canada, the mining sector in Canada released 15700 Kt CO2 equivalent of GHG (CO2, NOx, SO2) in 2003.12 Other air contaminants that are associated with the gold and base metals mining sector include: cadmium, mercury, nickel, lead, arsenic and chromium.13 Waste water and water contaminant release is a major concern for the mining industry. The types of contaminants released vary depending on the type of metal being mined. For gold mining, water contaminants may include Arsenic and Mercury.14 For base metals mining, the contaminants released can include: cadmium, mercury, nickel, and lead.15 When underground mining for gold or base metals encounters groundwater, the oxidation of the sulphur-bearing rocks can cause the release of H2SO4 (acid mine drainage) into the groundwater.16 There are massive amounts of solid waste that result from the excavation process in the mining industry. All 11 No Dirty Gold Greenhouse Gas Inventory Data Search. Environment Canada. 2003. http://www.ec.gc.ca/pdb/ghg/query/index_e.cfm 13 Toxic Release Inventory. Chemical Fact Sheets .National Mining Association. http://www.nma.org/pdf/tri/tri_fact_sheets.pdf. 14 Dirty Gold Impacts. No Dirty Gold. http://www.nodirtygold.org/dirty_golds_impacts.cfm 15 Ayers et al. The Life Cycle of Copper, its Co-Products and By-Products. Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development, 2002. 16 Cohen, R. of microbes for cost reduction of metal removal from metals and mining industry waste streams. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2006. 14; 1146-1157. 12 4 overburden, including top-soil and vegetation, must be removed in order to commence surface mining. Also, waste rock must be removed from the mine and disposed of. An economical grade for a diamond mine is in the range of 5 carats per ton, according to Dr. J. Findlay,17 therefore leaving the majority of the rock as waste. Surface and groundwater contamination can occur at various stages of the extraction phase. The contamination can occur from slow seepage of contaminants due to poorly constructed waste storage facilities, by acid mine drainage, or by catastrophic failure of storage facilities of tailings and other waste products18. Local air quality can be greatly affected by the release of contaminants into the air and can have major implications to human and ecosystem health. The extensive surface area disturbance and land resources required for surface mining can have serious implications for biodiversity and ecosystem degradation if reclamation efforts are unable to restore an area to it’s original state (e.g. draining of Lac de Gras, NWT, Canada).19 The emission of greenhouse gases in the extraction phase can be a significant contributor to climate change. Phase 3: Processing The processing phase of the life cycle assessment involves the further refining of concentrated metals and diamonds of the mining process. Processing covers all aspects of the separation and concentration of the metals as well as diamond cutting and polishing. The most complex phase is the separation of metal ores and diamonds from surrounding waste rock materials. It is conducted using a variety of processes. The base metals that make up a gold ring, which form an alloy with gold, are silver, nickel, zinc, and copper. In order to extract metal ores (silver and gold) from the waste rock, several possible extraction methods can be used. Some of the processes used to separate gold from surrounding rock are: gravity, floatation, comminution, or magnetic processes. All of these separation processes require the use of water.20 Floating agents are often toxic, but are hydrolytically decomposed while still in the processing plant. Ore extraction is often done with either heat or water. The waterbased separation process—hydrometallurgy— is becoming increasingly common. Hydrometallurgy uses leaching liquids that are often acids, alkalis, salts, or other solvents, and the resulting waste water is polluted with remnants of these chemicals.21 Other methods involve large quantities of cyanide. One way of extracting gold from ore is to spray the ore with cyanide and induce the gold leaching out of the ore. Many mines use several tons of cyanide each day, and this cyanide-contaminated waste is usually abandoned. To put this into perspective, a rice-grain-sized amount of cyanide is fatal, and to extract enough gold for a single wedding band, 18 tons of waste-ore are produced. Today, the efficiency of the gold industry is very low: 0.00001 percent of ore (by weight) can be refined into gold; everything else is waste. Comparatively, copper mining performs little better, resulting in 0.51 percent of weight proportion of ore actually being usable copper. The amount of waste from the mining industry in the US is 9 times the 17 Findlay J. Personal Communication 1 October 2006. Dirty Gold Impacts 19 Diavik. http://www.diavik.ca/WCD.htm 20 Neved, Jansz. Waste Water Pollution Control in the Australian Mining Industry. Journal of Cleaner Production. 14 (2006); 1118-1120. 21 Ibid. 18 5 amount produced by US towns and cities combined. “In 2001, the most recent year for which data were available, metals mines produced 1,300 tons of toxic waste—46 percent of the total for all US industry combined—including 96 percent of all reported arsenic emissions, and 76 percent of all lead emissions.”22 Some of these toxic substances are naturally occurring, but are disturbed and released by the mining process, whereas others are intentionally added to the gold leaching process. The efficiency of mining and consumer awareness of their demands for metals has not changed as demonstrated by the continued growth of gold on the NY Stock Exchange. After the separation process, metal is melted into blocks at almost 100 percent purity, and is then sold to buyers who melt parts of the gold blocks to make the gold ring. This process uses intense heat and therefore consumes large amounts of electrical energy, which, depending on the region, is generated with either water or fuel. Rough diamonds, being the hardest material in the world, can only be effectively cut and polished using other diamonds and diamond film. Other substances, such as silica, are sometimes used in the cutting and polishing process; however diamonds are the tool of choice.23 The inputs into the ore and diamond processing systems are: electricity used to run the processing facility, and the fuels associated with transportation to the processing facility (if the processing takes place outside of the mining area); the chemicals used to separate rough diamonds, gold and metals from surrounding waste rock material; and the water used in the separation processes. The chemicals used in solutions designed to dissolve the “waste rock material” surrounding gold or diamonds can be released along with the sludge into the environment. The base-metal production process produces a lot of waste. Some examples of the waste that results from the extraction of solid metals include: large amounts of solids (gypsum, jarosite, slag, etc.), air and water pollutants (e.g. CO2, SO2, NOx , Cd, Ni, As, Pb.24 The environmental impacts associated with the processing of the metals and diamonds are airborne pollutants and water contamination. Airborne pollutants are associated with acid rain and the greenhouse effect. Waterborne pollutants are equally damaging, as they often reach the groundwater and can contaminate aquifers and other aquatic systems that are otherwise unassociated with the processing system. Phase 4: Manufacture / Retail Diamonds are a value-added industry. In 1981, the sale of rough diamonds straight from the extraction process was $2 billion. By the time diamonds reached the end of their “industry cycle,” they were sold to consumers for $18 billion.25 The diamond life cycle once it leaves the mine continues to “upgrade” the diamond. After the mining process, the rough diamond is sold to rough gem dealers who them sell it to cutting units, from where it proceeds to wholesale dealers, from where it finally goes to 22 23 No Dirty Gold Tang et al. A New Elegant Technique for Polishing CVD Diamond Films. Diamond and Related Materials. Aug. 2003. Vol. 12 Issue 8. 1411-1416. 24 Ayres 2002. Chang et al. The Global Diamond Industry. Chazen Web Journal of International Business. Fall 2002. http://www2.gsb.columbia.edu/journals/files/chazen/Global_Diamond_Industry.pdf 25 6 retail.26 All along the manufacturing process, the energy inputs are commonly associated with transportation, and the generation of electricity. The outputs associated with manufacturing are: the finished diamonds and jewellery; CO2 emissions from transportation, and energy production; and minimal amounts of solid waste. Because of the fuel involved in the transportation process, greenhouse gas emissions contributing to global climate change are the main environmental impact associated with the manufacturing stage. The DeBeers marketing campaign stating that “Diamonds are forever” is quite accurate. Diamonds are rarely discarded, and if they are, it is most likely accidental. Diamonds and diamond rings are passed down from generation to generation and are therefore an almost entirely recycled product. Major Environmental Impacts Summary The following summarizes the environmental impact of gold and diamond mining: Air Emissions Climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions during smelting of ore and in all aspects of transportation and construction. Local air quality degraded by gases released in processing and particulate matter expelled during extraction and processing. Water contamination Aquatic ecosystem degradation caused by seepage and major releases of toxins from contaminated waste water to surface water. Ground water contamination due to acid mine drainage and surface water contaminant seepage. Land resource use Decreased biodiversity, ecosystem degradation and soil erosion resulting from major land disturbance in sensitive environments and remote areas (e.g. tundra). Complete ecosystem destruction (lakes, forests, rivers) from failed reclamation efforts. Mining Sustainability Initiatives There are several mining sustainability initiatives that are formed either by international governing bodies such as the UN, international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), or industry standards organizations that promote the sustainability of the industry through voluntary cooperation. The following five initiatives are just an 26 Chang et al. 2002. 7 example of prominent industry and international standards that are currently at the forefront.27 Ceres Ceres is a national network of investors, environmental organizations and other public interest groups working with companies and investors to address environmental sustainability issues and challenges. Its mission is to integrate sustainability into capital markets across the world for the health of the planet and its inhabitants. Founded in 1989, Ceres’ vision incorporates business and capital markets to promote the well being of human society and the protection of the earth's biological systems and resources. Ceres established the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), a standard that is used by over 850 companies worldwide for corporate reporting on environmental, social, and economic performance28. From the results of the Ceres report, it is evident that corporate responsibility amongst metals and mining leaders is varied as many firms and corporations place different degrees of emphasis on environmental standards. In 2006, Ceres released a report that evaluated over 100 companies in 10 of the most carbon intensive sector industries in the United States that included the metals and mining industry. These companies are ranked as among the leaders in their industry and are evaluated according to a Climate Change Governance Checklist.29 This checklist is comprised of 14 governance steps scored on a 100 point scale that companies take to actively address climate change. There are 5 broad categories that comprise the 14 governance steps that include: Board Oversight (up to 12 points); Management Execution (up to 18 points); Public Disclosure (up to 14 points); Emissions Accounting (up to 24 points); and Emissions Management and Strategic Opportunities (up to 32 points).30 ISO ISO, the International Standards Organization, is the world’s largest developer of standards for a variety of industries. ISO is an NGO which aims to improve social, environmental, and technical standards. ISO sets out to bridge the gulf between private sector and public sector interests (ISO overview). International standards are beneficial to industry to ensure that their products are accepted in the global market so they have an incentive to abide by ISO standards. ISO strives to establish standards for environmental sustainability to better industry on a global scale. One fallback of being an NGO is that ISO has no power of enforcement, however many countries have adopted ISO standards as part of their legislative frameworks, and they hold a significant market impact in the 27 Newmont the Gold Company http://www.newmont.com/en/ Ceres www.ceres.org/ceres 29 Cogan, Douglas G. Corporate Governance and Climate Change: Making the Connection, Summary Report. Ceres, March 2006. 3. 30 Ibid. 3. 28 8 case of non-adherence. ISO standards are voluntary and non-regulatory, but have resulted from market demand and therefore have a large amount of sway. ISO certification also holds a lot of weight and is considered legitimate because of a third party audit certification system to ensure compliance with ISO standards, and quality control. United Nations Global Compact The UN Global Compact is a non-regulatory framework for the mining industry promoting accountability and transparency. It is a corporate responsibility initiative emphasizing four universal values: human rights, environmental sustainability, labour, and anti-corruption. The three principles that focus on environmental sustainability are Principles 7, 8, and 9: Principle 7 Business should support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges; Principle 8 Undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility; Principle 9 Encourage the development and diffusion of environmentally friendly technologies.31 International Council on Mining and Minerals (ICMM) – Global Mining Initiative (GMI) The ICMM is a voluntary industry initiative with the following Principles of Sustainable Development: 1) Implement and maintain ethical business practices and sound systems of corporate governance 2) Integrate sustainable development considerations within the corporate decisionmaking process 3) Uphold fundamental human rights and respect cultures, customs and values in dealings with employees and others who are affected by our activities 4) Implement risk-management strategies based on valid data and sound science 5) Seek continual improvement of our health and safety performance 6) Seek continual improvement of our environmental performance 7) Contribute to conservation of biodiversity and integrated approaches to land-use planning 8) Facilitate and encourage responsible product design, use, re-use, recycling and disposal of our products 9) Contribute to the social, economic and institutional development of the communities in which we operate 10) Implement effective and transparent engagement, communication and independently verified reporting arrangements with our stakeholders.32 31 About the Global Compact: The Ten Principles. The United Nations Global Compact. http://www.unglobalcompact.org/AboutTheGC/TheTenPrinciples/index.html 32 2005 Annual Report NYSE. Newmont the Gold Company. Accessed 28 October, 2006. 9 World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) – Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project (MMSD) The purpose of the MMSD is to empower industry and business leaders to become catalysts for change in the industry to ensure that mining develops and continues in a sustainable manner.33 International Development and Research Council (IDRC) – Mining Policy Research Initiative (MPRI) The MPRI is primarily aimed at addressing mining issues in Latin America and the Caribbean. The Initiative serves to identify key stakeholders, ensuring greater corporate social responsibility. IDRC increases regional networking to ensure that needs of the region and the industry are addressed and discrepancies are resolved. Two major focuses of the initiative are indigenous peoples and mining technology innovation.34 World Wildlife Fund (WWF) - Mine Certification Evaluation Project (MCEP) The World Wildlife Fund has several initiatives on responsible mining and mining sustainability. One of these WWF initiatives is the Mine Certification Evaluation Project (MCEP), which audits the industry auditors. The WWD takes into account water and air pollution, as well as the displacement of ecosystems and people, and strives to ensure that the industry is held accountable for not upholding treaties and ignoring regulations. The World Wildlife Fund’s MCEP ensures that industry practices are transparent, and that they will continue to spearhead future sustainability initiatives.35 Publicity Campaigns The most well known ENGO publicity campaign was against “blood diamonds.” It was mainly a campaign to highlight socio-political issues surrounding the diamond trade in Sierra Leone. It was a fairly effective campaign, which proved to be beneficial for the Canadian diamond industry, allowing them to laser brand their diamonds with the image of a polar bear and market them as “clean diamonds”, not associated with the violent diamond trade of Sierra Leone and other conflict areas. The No Dirty Gold campaign by Earthworks is relatively new and has had an effect on jewellers. Thus far they have enlisted a number of large jewellery manufacturers and marketers (Zale Corp., Sterling, Tiffany & Co., Helzberg Diamonds, Cartier, Fortunoff, Val Cleef & Arpels, Piaget) to promote sustainable and environmentally responsible gold mining by only purchasing gold from approved mining companies. http://www.newmont.com/en/investor/releases/media/newmont/2005_Annual_Report.pdf 33 The Mining, Minerals, and Sustainable Development (MMSD) Project. International Institute for Environment and Development. http://www.iied.org/mmsd/what_is_mmsd.html 34 Mining Policy Research Initiative (MPRI). International Development Research Council: Environment and Natural Resource Management. http://www.idrc.ca/minga/ev-70315-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html 35 Mining Certification. World Wildlife Fund. http://wwf.org.au/ourwork/industry/mining/ 10 However, the effects of this campaign are limited and need to attract greater attention to affect a greater impact on the jewellery manufacturers. Jewellery Sector Initiative: The Jewellers of America have formed the Council for Responsible Jewellery Practices (CRJP) to promote “responsible, ethical, social and environmental practices throughout the diamond and gold jewellery supply chain, from mine to retail”36. Interestingly, both BHP Billiton and Newmont Mining are founding members of the CRJP. This initiative appears to be in the initial stages and very limited in its scope and overall effect. Effect on Jewellery Sector Jewellery manufacturers are mostly unaffected by the environmental issues associated with the mining industry. Some public pressure due to ENGO campaigns concerning environmental and socio-political issues has had a limited effect, instigating a slight shift in behaviour of the jewellery sector. Canadian Policies and Regulations Fisheries Act Metal Mining Effluent Regulations (SOR/2002-222) The Regulations […] impose limits on releases of cyanide, metals, and suspended solids, and prohibit the discharge of effluent that is acutely lethal to fish. The Regulations also require metal mines to conduct Environmental Effects Monitoring programs to identify any adverse effects of their effluent on fish, fish habitat, and the use of fisheries resources37. Waste Discharge Regulation Implementation Guide Issued by the Government of British Columbia, on July 8th, 2004 to integrate and replace the previous Environmental Management Act and the Waste Management Act. The Waste Discharge Regulation Implementation Guide (WDRIG), only allows certain industries to release waste into the environment, and regulates the amount of waste that these industries can release: 36 What We Stand For. Council for Responsible Jewellery Practices. http://www.responsiblejewellery.com/what.htm 37 Fisheries Act: Metal Mining Effluent Regulations. Acts Administered in Part by the Minister of the Environment. Environment Canada: Environment Acts and Regulations. 1979. http://www.ec.gc.ca/EnviroRegs/Eng/SearchDetail.cfm?&intReg=174 11 Schedule 1 Industries, trades, businesses, operations and activities listed on Schedule 1 of the regulation will generally continue to be authorized through the use of site specific authorizations or regulations due to the complexity of their discharges, potential for significant environmental impacts or limited number of similar operations in the province. Schedule 1 also includes some industries, trades, businesses, operations and activities that are authorized by existing regulations. Schedule 2 Industries, trades, businesses, operations and activities listed on Schedule 2 of the regulation are eligible to be governed by minister’s codes of practice. Codes of practice are enforceable, standard industry- or activitywide regulations governing the discharge of waste from a prescribed industry or activity. If a code of practice governs the industry, trade, business, operation or activity, no site-specific permit or alternate type of authorization to authorize the introduction of waste into the environment is required. In the absence of an approved code of practice, other forms of authorizations are required to authorize discharges to the environment.38 Metal Mining: the Dirty Reality The metal mining industry is among the most environmentally impactful industries in the world. For every ounce of gold that comes out of the world’s mines, 79 tons of mine waste is produced. Mining for metals, employs 0.09 percent of the world’s population, yet consumes 10 percent of the world’s energy consumption, and accounts for 96 percent of the US’s arsenic emissions.39 The gold industry is very inefficient, requiring 18 tons of waste ore to produce enough gold for a single wedding band. The use of cyanide to leach the gold out of the ore is very toxic, with a grain-sized amount being fatal.40 Cases: Leaders and Laggards in the Mining Industry The Laggard: Newmont Mining Newmont, one of the world’s most prominent gold mining companies, scored 24 points among the metals and mining industry with Alcan scoring a high 77 points. Ceres environmental standards are voluntary amongst companies and many governments both locally and nationally do not enforce penalties for non-compliance. 38 Waste Discharge Regulation Implementation Guide. British Columbia Ministry of the Environment, Environmental Protection Division. 2006. http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/epdiv/env_mgt_act/pdf/wdr_implement_guide.pdf 39 40 Dirty Metals. No Dirty Gold. http://www.nodirtygold.org/pubs/DirtyMetals_HR.pdf Ibid. 12 Company Profile Newmont Mining is the largest gold mining company in the world. They have mines in North and South America, Asia, Australia, and Indonesia, and continue to conduct widespread mining exploration. Newmont’s mines also produce copper, silver, and zinc, which are all major components of gold jewellery production. Founded in 1921 in New York, they have been publicly traded on the New York Stock Exchange since 1925. Today, they employee 28 000 people, and profess to be leaders in sustainable mining.41 Environmental and Sustainability Initiatives Newmont Mining makes various claims to being a leader in mining sustainability initiatives. The company claims to lead the industry in transparency and accountability. They market themselves as one of the founding members of the ICMM and of the Council for Responsible Jewellery Practices. Newmont is also a signatory of the UN Global Compact and are signatories of the International Cyanide Management Code. According to Newmont Mines, they set the highest standards of community development initiatives and environmental stewardship.42 Unfortunately, despite these initiatives of which they are founders and signatories, the reality proves different. Performance The No Dirty Gold Campaign is a good industry watchdog which incorporates all the mining issues that Greenpeace, Earthwatch, the World Wildlife Fund, and others cover in their extensive research of mining companies and their environmental and social impacts. Thus, their compilation is the source for the following environmental and social impacts of Newmont Mining around the world. Ghana Several Environmental Impact Assessments on their mining activities in Ghana suggest that they are not adhering to the International Cyanide Management Code, and that there is no evidence of financial backing for mine cleanup and reclamation. Although Newmont is claiming transparency as one of their core values, they are not disclosing potential significant acid generation from mine waste. On the social side, the involuntary displacement of subsistence farmers by mining activities threatens food security in the area.43 Indonesia In Indonesia, Newmont’s mining activities are near a fishing village, where particular consideration should be paid to the livelihood of the surrounding community and the ecosystem of the waters in the area. Instead, Newmont dumps about 120,000 tonnes of mine tailings a day directly into the ocean—an illegal activity in North America. This activity has caused the relocation of several fishing villages because of all 41 Newmont 2006. www.newmont.com/en Ibid. 43 Communities Affected by Newmont Speak Out. No Dirty Gold. 27 April 2005. http://www.nodirtygold.org/newmont_communities.cfm 42 13 the marine pollution. They have also dammed two rivers, threatening protected forests and causing further displacement of peoples.44 Peru Peru is a serious problem area for Newmont Mines. There are numerous claims that a mercury spill about six years ago still causes problems with child development and the health of the indigenous population that lives around the mining area. Newmont has not responded to these claims, and has not performed an official health investigation.45 Romania Most of the focus on the development of the Romanian mine has been on the social consequences. The operation is to consist of four open-pit mines in the denselypopulated Rosia Montana valley, with an unlined cyanide storage pond in the neighbouring Corna Valley. If the project goes ahead despite mass opposition, it would be the largest open-pit mine in Europe, in an area with archaeological value comparable to that of Pompeii. This mine would also require the demolition of 900 homes and the displacement of 2,000 people from the area. Romania and Hungary, the two countries that would also be impacted, have voiced their concerns about pollution from the mine.46 Nevada Finally, one of Newmont’s mines located on the Western Shoshone Nation’s Land of Nevada, has been developed without the approval of the Shoshone Nation. It threatens to leave significant land scarring, and pollution of groundwater. Groundwater depletion is also a major concern in the area, as is the emission of mercury, and air and water pollution caused by Newmont’s mining activities.47 Compliance to the initiatives that Newmont Mining has signed is difficult to impose as most of the treaties are non-binding, voluntary, and unenforceable. Also, in the private sector, as long as profits are made—and Newmont’s stock values keep rising—there is very little incentive to change. There is currently no regulatory body besides government, which would keep the industry in line. Public opinion is powerful, but money talks, and in the end, the effect of public opinion on profits will be the one to effectuate change in the industry. The Leader: BHP Billiton BHP Billiton is widely considered, within the mining industry and the financial sector, as a leader in sustainability practices and environmental performance. They scored 64 out of 100 on the CERES Climate Change Governance Checklist, where the average for mining sector was 42.2.48 Also used as a measure of environmental performance the Roberts Environmental Center developed the Pacific Sustainability Index (PSI), which is based on environmental and social intent, reporting and performance. The overall score from the PSI for BHP Billiton was a B+ (Roberts Environmental Center). The Dow Jones 44 Ibid. Ibid. 46 Ibid. 47 Ibid. 48 Ceres 2006 45 14 Sustainability Index (DJSI) named BHP Billiton the sustainability leader for the mining sector in 2006 (see Appendix B).49 Company Profile BHP Billiton was formed in 2001 from the merger of BHP and Billiton Resources. Incorporated in 1885, BHP was headquartered in Melbourne, Australia and had three main operations: minerals, petroleum, and steel. Billiton had been an active mining company since 1860, were Headquarters in London with operations that were focused predominantly on minerals and coal.50 Currently BHP Billiton employs 38,000 employees and has over 100 operations in 25 countries. Their operations are spread across a wide array of mining activities, including: aluminum, coal, copper, manganese, iron ore, uranium, nickel, silver, titanium, oil and gas, liquid natural gas, and diamonds. Their after tax profit in 2006 was calculated at US $10.2 billion.51 BHP Billiton is a global company, with extremely diverse interests. BHP Billiton’s operation of greatest interest to the Canadian diamond industry is the EKATI mine in the Northwest Territories of Canada. The EKATI diamond mine has two open pits (Koala and Misery) currently in production, two in development (Beartooth and Fox) and seven pits in total planned.52 Environmental and Sustainability Initiatives BHP Billiton has been ranked as a leader in the mining industry because of their clearly defined sustainability development policy and goals; transparency in environmental impact reporting; support of numerous international environmental initiatives; and leadership on new proactive eco-certification programs. BHP Billiton’s policy on health, safety, the environment and the community (HSEC) clearly states the goals, principles and guidelines for future sustainable development of the company and its operations. Under the HSEC they have set numerous benchmarks for sustainability with the ultimate goal of “Zero Harm” to the environment and affected communities. [BHP Billiton aspires to the principle of] to Zero Harm to people, host communities and the environment, and strives to achieve leading industry practice. Sound principles to govern safety, business conduct, social, environmental and economic activities are integral to the way we do business.53 49 DJSI STOXX - Supersector Leaders. 2006. DJSI. http://www.sustainability-index.com/djsi_pdf/Bios06/CBR_BHP_Billiton_06.pdf 50 BHP Billiton. Company Overview. BHP Billiton. http://www.BHP Billitonilliton.com/bb/aboutUs/companyOverview.jsp 51 Ibid. 52 Ibid. 53 BHP Billiton’s Sustainable Development Policy. BHP Billiton. 2005. http://www.BHP Billitonilliton.com/bbContentRepository/docs/SustainableDevelopment/policiesAndKeyDocuments/HSEC Policy.pdf 15 BHP Billiton is involved in a number of international initiatives for sustainability in the mining industry. BHP Billiton is a signatory to the United Nations Global Compact, a member on the World Business Council for Sustainable Development and a founding member of the Global Mining Initiative. They are also active in the International Council on Mining and Minerals and have endorsed the recently developed Sustainable Development Framework.54 BHP Billiton is also working on some pro-active programs on eco-certification like the Mine Certification Evaluation Project, and the Green Lead project, which are attempting to develop certification frameworks for mine sites and lead producers.55 Performance According to the HSEC targets scorecard, BHP Billiton has achieved or exceeded all of their short term goals set for environmental performance, with regard to greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption, waste management and product stewardship. All of the benchmarks set for the goal of “Zero Harm” have not been achieved or are behind schedule.56 The Roberts Environmental Center Pacific Sustainability Index (PSI) ranked BHP Billiton very high in intent, moderately high in reporting but graded them very poorly for performance in both the environmental and social categories. Upon further investigation there is a discrepancy in BHP Billiton’s reporting and self assessment, as well as other environmental non-governmental organization (ENGO) reports. This discrepancy calls into doubt the veracity of the company’s environmental reports and assessment. The following selected issues are currently being reported: Liability for the ongoing environmental devastation at Ok Tedi will return to haunt BHP Billiton. A court case is currently underway in Melbourne regarding BHP Billiton’s failure to live up to its obligations under a settlement agreement with the affected landowners of the infamous mine that destroyed a river system. BHP Billiton cleverly attempted to limit its liability for the ecological disaster caused by its Ok Tedi mine by placing its shares of the mine in a trust fund from which compensation payments to landowners would be made, and succeeded in gaining indemnity for any damages that will exceed the amounts in this trust fund. …efforts by BHP Billiton to pressure the Indonesian government to allow it to mine in protected forests where open cut mining is currently banned. BHP Billiton had committed internationally not to attempt to undermine laws of countries in which it operated... Dumping Mine Tailings and Wastes into the Oceans At Gag Island (Indonesia), BHP Billiton is considering submarine tailings disposal- the 54 BHP Billiton 2003 Health Safety Environment and Community Report. Roberts Environmental Center. http://www.roberts.cmc.edu/PSI/AutoReports2.asp?ReportNameID=712 55 56 Ibid. BHP Billion 2005 Sustainable Development Policy 16 disposal of mine wastes and tailings into the ocean – currently operations are suspended.57 The Canadian Mining Experience Diavik Mines Diavik is a Canadian diamond mine located 300 km northeast of Yellowknife, Northwest Territories in the Lac De Gras area. Diavik is a subsidiary of Rio Tinto plc of London, England. The lake is now part of the mining operation, as diamonds are located below the lake. Diavik is unique in that it is ISO 14001 certified, and maintains high ecological protection standards in its industry. Diavik is also a joint venture between Aber Diamond Limited Partnership which owns 40percent of the operations, and Diavik Diamond Mines Inc. which is responsible for 60percent of mining operations. The Diavik mine holds a relatively small amount of diamonds by global mine standards, however, the diamonds that originate in the Diavik mine are of the highest quality, with “some of the world’s highest per tonne ore value”.58 Mining started in 2003, and is expected to last for 16-22 years. Corporate Social Responsibility Diavik recognizes that it is located in a pristine area in northern Canada. They also recognize that they are located on a lake, and in the middle of the caribou migration route. As such, with local partnerships and consultations with local stakeholders and interest groups, Diavik has developed a sustainable development policy, and has attained ISO 14001 certification. These environmental sustainability initiatives set out a long term goal of treating all water re-released into the environment, ensuring that toxins are not introduced into the area, and that mine restoration will take place to restore the area to as natural a state as possible59. Although mining operations will remove fish habitat temporarily to access the ore through rockfill dike construction in 0.5percent of the lake area, full restoration of the lake will take place after mine operations shut down. In the meantime, the other side of the dike will form new fish habitat to compensate for the temporary loss. “As per Canadian Fisheries Regulation, there will be no net loss of fish habitat.”60 Also during mining operations, the end of mine-life will be kept in sight. The recreation of fish habitat is such an example, as is the “contouring of country rock piles to create smooth hills that allow caribou safe access” (Diavik). In 2000 prior to mining 57 BHP: The Quiet Deceiver. 2003. Mineral Policy Institute (MPI). Media Background Briefing. http://www.mpi.org.au/companies/BHP Billiton/bhp_deceiver/ 58 Diavik. http://www.diavik.ca/WCD.htm 59 Ibid. 60 Diavik. http://www.diavik.ca/WCD.htm 17 activities, Diavik entered into an Environmental Agreement with local Aboriginal groups, and can therefore be help accountable for their activities in the mine area. Ekati Ekati is another Diamond mine also located 300km northeast of Yellowknife, in the Northwest Territories. Ekati, unlike Diavik, performs open-pit mining, as well as underground mining operations.61 There is little evidence to suggest that they are proactively working to protect the fragile environment in which they conduct their operations. Sullivan Mine, Kimberley BC Located near the Alberta border in Kimberley, British Colombia, the Sullivan Mine deposit was rich in resources with zinc, lead, and iron. After 92 years of activity, the Sullivan mine closed its production in 2001 totalling over $20 billion in revenue during its operations. Teck Cominco is currently overseeing the extensive decommissioning and reclamation process of the mine. Tasks that have been undertaken by Teck Cominco include reclaiming disturbed lands, a property wide human health and ecological risk assessment, contaminated site assessments, and the demolition of operational/building structures no longer in use. Also being undertaken is the establishment of an underground mine dewatering system that will collect contaminated waters for delivery to the Drainage Water Treatment Plant (DWTP) for final processing before being discharged into the St. Mary River.62 Effluent discharge of water from the DWTP that removes contaminated water associated with acid rock drainage has met all BC Ministry of Water, Land, and Air Protection (MWLAP) permit requirements. This includes 0percent mortality to fish exposed to 100percent effluent water over a period of 96 hours. The underground mine dewatering system uses the mine’s underground workings to store contaminated water and progress will continue to be made in this area with ongoing ecological assessments.63 In 2004, 162 hectares of land were prepared for reclamation and 18 hectares were seeded. No woody species seedlings were planted in 2004 but 54,000 seedlings representing 17 woody species were planted in 2005. An additional 115 hectares of tailings ponds were covered with glacial till, the second layer of the soil cover system. Seventeen hectares of miscellaneous linear disturbances (rail beds and launder routes) were reclaimed and 30 hectares, which made up the open pit waste dump, were prepared for grass and woody species planting in 2005. Reclamation work which started at the site over 12 years ago is revealing a degree of success as evidenced by the wildlife migrating to the reclaimed areas.64 Teck Cominco continues to engage and participate with the community in the City of Kimberley, aiding the transitional development from mining community to a 61 Ekati. http://ekati.BHP Billitonilliton.com/default.asp 62 http://www.teckcominco.com/operations/sullivan/sustainability.htm accessed January 15th 2007. Ibid. 64 Ibid. 63 18 more diversified economic and social city. Teck Cominco has also offered to make land available for a light industrial park and has worked with the city to turn over the remaining portions of the main water system to the city. An agreement was also finalized with the city to utilize portions of Teck Cominco lands under a license of occupation, for the purpose of establishing an integrated walking, biking and skiing trail system.65 The Teck Cominco example with the decommissioning of the Sullivan Mine reveals the corporate responsibility that a corporation is undertaking after the lifespan of its resources to make a community more sustainable as well as environmentally safer. Other companies need to build upon success stories such as this case study. Holloway Mine In Ontario, the Holloway Mine operated by the gold giant Newmont Mining is another case study where corporations are striving to be more socially and environmentally responsible to the community and surrounding environment. Located east of Timmins, Holloway’s environmental strategy is to remain compliant with government regulations and industry standards especially in the case of emissions, while maintaining effective monitoring and control programs to protect the environment. In 2004 the acquisition of the nearby Barrick’s Holt-McDermott mill required Holloway to incorporate new disciplines into its environmental management system, such as cyanide and tailings (waste rock) management.66 The tailings are placed into confined ponds to allow the metals to settle out and for diluted cyanide to be broken down before the water is discharged into the environment by using natural degradation. The natural degradation process involves retaining the discharged mill process water for a period of time sufficient to allow for the natural breakdown of cyanide, and for the associated precipitation of heavy metals previously forming complex cyanide compounds.67 The Holloway mine has also pursued other means of recycling waste water in order to reduce the amount of dependency on the nearby Magusi River. Until October 2004, Holloway had an agreement with the amalgamated Barrick’s Holt-McDermott mill to reuse all of Holloway’s underground water during the milling process. As a result, there is no effluent discharge into the environment by Holloway and the amount of fresh water used has been reduced. Sampling and monitoring of the mine’s water continues according to the certificate of approval.68 The mine is not expected to close for another several years but the site has been identifying areas of contamination or potential contamination that needs to be addressed before further environmental damage can occur. The mine has an approved environmental closure and reclamation plan that outlines environmental activities that 65 Ibid. http://www.newmont.com/en/operations/nthamerica/holloway/social/index.asp accessed January 15th 2007. 67 Ibid. 68 Ibid. 66 19 will occur after the mine closes. The plan will cover public health and safety issues, land rehabilitation, and minimal environmental impact.69 Sustainability Issues and Options In the life cycle of a diamond ring, the exploration and manufacturing phases are the biggest concern for environmental impacts. The mining industry is under extreme pressure to develop and extract resources in a more sustainable manner, with limited deleterious effects on the natural environment. The mining industry has reacted to this pressure by instigating and signing onto a number of initiatives and policies aimed at reducing the overall environmental impacts of their operations. The initiatives are ambitious but the performance does not seem to be achieving the goals set out. Even those companies considered to be the leaders in sustainable development do not seem to be making significant progress in limiting their environmental impact. The jewellery manufacturers and retailers are becoming increasingly affected by the growing emphasis on sustainability in the mining sector. The connection between jewellery and the environmental impacts of the mining industry is an important issue for the modern consumer. The jewellery manufacturers are not greatly affected by the pressures that are predominant in the mining sector. There is no connection in the mind of the consumer between the jewellery that they purchase and the environmental impacts of the mining industry. Publicity campaigns are limited but, when used, do seem effective in raising awareness of the environmental and social issues that are associated with the production of a diamond ring. The purpose of this report is to investigate the environmental performance and responsibility of the jewellery sector and to make recommendations for improvement. There are a number of initiatives that jewellers can pursue in order to improve their overall environmental responsibility. The most effective would be targeted at improving the mining industry’s performance. Major Stakeholders The Mining Sector Environmental Issues There are three main areas that raise environmental concerns for the mining sector: air emissions, land resource use and water contamination. The main problems associated with air emissions are the greenhouse gases produced in the mining process, which contribute to climate change, as well as local air quality degradation caused by gases and particulate matter expelled during extraction and processing. 69 Ibid. 20 In the course of mine development large-scale land disturbance can occur in sensitive environments and remote areas (e.g. tundra) resulting in decreased biodiversity, ecosystem degradation and soil erosion. Also, complete ecosystem destruction (lakes, forests, rivers) can result from failed mine reclamation efforts. Toxins from contaminated waste water that are released into surface water can cause aquatic ecosystem degradation. Acid mine drainage and surface water contaminant seepage can also cause ground water contamination. Mining Sustainability Initiatives Several sustainability initiatives exist, both domestically and internationally. Often, international initiatives are designed to apply to all signatories in all countries. Such sustainability initiatives include, but are not limited to the following: 1) The United Nations Global Compact 2) The International Council on Mining and Minerals (ICMM)—Global Mining Initiative (GMI) 3) The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD)— Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project (MMSD) 4) World Wildlife Fund (WWF)—Mine Certification Evaluation Project (MCEP) All of these initiatives share a common set of underlying values. Namely, they emphasize increasing accountability, increasing transparency, decreasing environmental impact, minimizing social impacts, and cleaning up their practices to ensure that there are no negative health impacts on adjacent communities. Unfortunately, these initiatives are all voluntary, and non-regulatory. Since international initiatives are not being effectively enforced, and the industry has little incentive to abide by these initiatives, consumers and the retail end of the chain may then offer the solution by putting pressure on producers and miners by steering the market in the desirable direction. The Jewellery Sector Current Sustainability Initiatives The key to a successful awareness campaign is the introduction of consumer choice. Responsible jewellers recognize the need for change in the mining and processing sector, and work together toward achieving a sustainable jewellery life cycle. One such jewellers’ council already exists: The Council for Responsible Jewellery Practices (CRJP). They are a non-profit organization that seeks to better the entire life cycle of gold and diamond jewellery. They aim to create a “Responsible Policies Framework” for their members; require the implementation of the framework that requires “self-assessment and is evidenced through a system of independent third party 21 monitoring;” they advise and promote this framework; and they will promote the ethical, social, and environmental responsibility of the business community.70 This initiative is in the early stages of development, but looks at the initiatives that affect the industry from the jewellers’ perspective. This is a key, retail driven, initiative to promoting sustainable mining practices, since the end of the jewellery supply chain—consumer opinion in general—is the determinant of the market. The Council’s idea is admirable; however there seems to be little power of enforcement. No Dirty Gold Campaign The No Dirty Gold Campaign follows the format of the Blood Diamonds campaign and is beginning to address the impacts of gold mining on societies and the environment. Initially targeted as a consumer education campaign, some of the bigger jewellery manufacturers have since signed onto the initiative. These signatories have committed to purchasing gold from mines that meet a minimum set of criteria. The criteria include stakeholder and community involvement and guaranteed funds for mine reclamation. If the No Dirty Gold campaign is as effective as the Blood Diamonds campaign, it could influence jewellers to pressure the gold mining companies to improve environmental performance. Jewellery Organizations There are a number of jewellery associations that have recently adopted environmental responsibility initiatives, two of which include CIBJO the World Jewellery Confederation and the Jewellers of America (JA). CIBJO is an international confederation of national jewellery organizations. Its Corporate Responsibility Initiative is a very general document that focuses mainly on sales practices and conflict diamonds and relies completely on self-monitoring. The document’s only reference to the environment is the following: “…full compliance with international best practice and the related regulatory framework with respect to the environment.”71 There is a need to know what the effects of non-compliance with international initiatives are on the jewellery industry. The Jewellers of America’s has a Supplier’s Code of Conduct which provides guidelines for assessing the suitability of metal and gemstone providers. It is a four page document dedicated predominantly to employee rights, child labour and ethics. There is one paragraph dedicated to the environment which states: “…it is therefore in the industries best interest to ensure that the minerals upon which it depends are obtained, produced and used in environmentally and socially responsible ways.”72 This statement does not address any specific issues and has no guidelines for assessment of suppliers and their practices. 70 CRJP Code of Ethics – Commitment. CIBJO The World Jewellery Confederation. http://www.cibjo.org/commitment.html 72 Corporate Responsibility. Supplier Code of Conduct. Jewelers of America. http://www.jewelers.org/pdf/CorporateResponsibility/SupplierCode.pdf 71 22 The environmental responsibility initiatives of the jewellery organizations are weak documents that do not address the environmental issues associated with the mining industry. Both documents have a separate section dedicated to “conflict diamonds,” which is a result of the bad publicity created by the Blood Diamonds campaign and the internationally recognized Kimberley Accords of 2002 that were signed by both the diamond industry, and international governments to combat the trade of diamonds in conflict zones.73 Recommendations Independent Certification and Monitoring It would be effective for the jewellery manufacturing industry to create a third party monitoring group consisting of industry, government and public stakeholders, which would evaluate the environmental sustainability of mines and producers. This independent group would have the authority to grant certifications, impose fines and create regulations. Certification should be based upon stakeholder and industry constructed criteria. The fines charged must be significant enough to act as deterrents to non-compliance. Collected fines can be used to develop environmentally sustainable technologies. Self-regulation methods are a solution to the high costs associated with enforcement by governments, and they benefit the industry as they will promote innovations and clean processing and mining practices. If jewellers were to purchase only from certified suppliers, they would influence the mining industry towards compliance with certification guidelines. Enforcement The voluntary and non-regulatory nature of international enforcement initiatives impedes their effectiveness, especially considering the associated costs. Without any consequences to face for ignoring enforcement, mining companies and jewellery producers have little incentive to abide by the initiatives they have signed. Mining in developing countries presents increasingly complex cost and compliance issues. Government enforcement regimes tend to be costly, and host governments, which have a myriad of local social or geopolitical issues to address and enforce, cannot be relied upon to take action against visiting industry in the name of environmental standards. 74 Lack of enforcement is an impediment to improving the mining company’s environmental performance standards. This regulatory void puts the jewellery sector in an important position of influence; its support of third party monitoring and certification would give the sector influence in assessing international industry practices, particularly in developing or underdeveloped countries. The jewellery sector has the power to hold 73 Diamonds in Conflict: The Kimberley Process. www.globalpolicy.org/security/issues/diamond/kimberlindex.htm 74 Paquin M, Sbert C. Toward Effective Environmental Compliance and enforcement in Latin America and the Caribbean. UNISFERA: Centre International Centre. November 2004. http://www.unisfera.org/IMG/pdf/New_approaches_to_environmental_protection_vfinal3_ajout_.pdf. 23 mining companies accountable, and to encourage them to improve mining standards in developing countries to coincide with standards in more developed regions. Consumer Education Self-assessment and self-regulation may also offer a company a competitive edge over others. Incentives coming from the jewellers themselves, greatly impact the industry, as exemplified by the Blood Diamonds campaign against DeBeers and other large diamond miners and producers. The Blood Diamonds campaign was so successful, that global awareness effectuated change in these industries, and improved social and human resources practices were put in place. That is not to say that the industry is without flaws with regard to the social aspect, however consumer pressures have put pressures on the jewellers who have then put pressure on producers and miners. Consumer awareness can therefore be deemed essential to the success of environmental sustainability initiatives as well. Therefore, it is important to impact consumer awareness through campaigns promoting ethical mining practices. The No Dirty Gold Campaign is taking the example of the Blood Diamonds campaign and is beginning to address the impacts of gold mining on societies and the environment. Diamond and gold rings have enormous value-added potential. At the bottom of the chain, at the jewellery store, the diamonds have a relatively large financial impact. If the monetary value of a purchase is large, consumers spend more time evaluating the product. If jewellers themselves claim to deal only with ethical mines, then they can market themselves as ethical and sustainable companies. This campaign has worked with the market for Canadian diamonds which were initially marketed as “ethical diamonds.” Through consumer awareness, and pressures on the industry from the jewellers who purchase cut diamonds, an impact on the mining end of the industry can be quite significant. Culture changes can shift market direction. Jewellers can then take it upon themselves to impact the entire life cycle of gold and diamonds by forming councils and regulatory bodies to audit their suppliers. Jewellers hold a lot of power, since they supply the demand for jewellery, and as such, by prioritizing environmental sustainability, they would truly impact the entire industry. . Eliminating Mining from the Life Cycle: Golden Circle Jewellers Golden Circle Jewellers is a jewellery manufacturer and retailer that will attempt to sever the connection between mining and jewellers by using 100 percent postconsumer materials. The concept of recycling jewellery is not new, but a business concept that capitalizes on emerging marketing opportunities associated with increasingly environmentally-conscious consumers is. Golden Circle Jewellers will operate in a small to medium sized community (e.g. Halifax) and marketed as an alternative to the bigger trans-national jewellery manufacturers. GCJ does not eliminate the need for mining activities globally, it fills a niche market with a huge growth potential. Despite a 50 year supply surplus of gold, approximately 2, 500 tonnes are mined every year. Increasing the use of recycled materials for jewellery would reduce overall demand for mined metals. This decrease in demand would indicate a shift in consumer priority and the mining industry would be pressured to improve their public image by adopting sustainable practices and decreasing environmental impacts. 24 Vision Golden Circle Jewellers (GCJ) removes the link to unsustainable mining practices and “closes the loop” in jewellery manufacturing. The vision of Golden Circle is to use only post-consumer materials, minimize or eliminate all ecological impacts, effectively remove mining from the life cycle of its products and ultimately achieve a minimum ecological footprint. Golden Circle Model The Golden Circle model involves two separate phases termed the outer circle and the inner circle. The two phases of production are determined by the consumer, based on availability of recyclable material and customer preference. GCJ has a goldsmith / metal smith on staff who will manufacture and design jewellery to specifications set by the customer. The Outer Circle The outer circle refers to the manufacturing of jewellery using recycled metals obtained from an external supplier. The facilities of each of the metal recyclers will be visited and must meet a set of minimum environmental requirements. The recycling facilities must be located in eastern Canada, adherent to Canadian environmental regulations, ISO 14001 certified and they must have minimal discharges. GCJ will work in conjunction with facility staff for the implementation of eco-efficiency strategies. Whenever possible the distance of the shipped materials will be minimized. The environmental impacts of the outer circle are externalized to the individual metal recycling facilities and all attempts will be made to consult with the recyclers for minimizing their environmental impact. GCJ offers consumers in the outer circle the opportunity to make a donation to finance the planting of trees on a GCJ-owned tree plantation to counter-balance the emissions produced from the large scale smelting involved in the metal recycling process. Canadian diamonds can be supplied on customer demand, but all efforts will be made to acquire materials that are recycled from previously enjoyed jewellery. Once the materials are acquired the consumer enters the inner circle. The Inner Circle Once into the inner circle, the materials enter a closed loop system, which means that all of the environmental impacts are controlled and minimized. All of the buildings operated by Golden Circle Jewellers are powered using a combination of solar and wind power. Deliveries made within the Halifax area are done by bicycle couriers, and if necessary, by a hybrid vehicle. A charcoal forge, using Forest Stewardship Council certified charcoal, is used to form the metal into jewellery. Product stewardship plays an integral role in the inner circle. All jewellery can be returned to GCJ and, for a processing fee, can be reformed and re-designed to suit the customer’s changing fashion needs. 25 Conclusion Given the nature of the mining industry, it is important to acknowledge that ecological sustainability in mining areas is a unique challenge. The key to protecting our resources and to ensure that society and nature remain as undisturbed as possible is a collaborative relationship between industry and government. Governments need to ensure that regulations that are in place are enforceable, and that companies are held accountable for mine reclamation. However, it is ultimately in the government’s interest to protect its people and resources, so they need to be actively involved in the mine reclamation process. Another important factor in ensuring sustainable mining is changing international initiatives into regulatory, enforceable rules. ISO 14001 is an effective way of certifying and monitoring mining activities. Diavik is a prime example of how mining can minimize its impact on the environment when adhering to international codes. To decrease the environmental impact of the life-cycle of the diamond ring, mining practises need to be cleaner, water needs to be treated, transportation throughout the process needs to be decreased, and new technologies need to be used to detect mine sites to decrease all aspects of the mining process. An important note about the jewellery life-cycle is that a change at any level of the cycle will affect it entirely. Consumer awareness and changing the demand will have the strongest effect on the life-cycle, as it will require a change in practice if market forces are to remain steady. Money talks, and consumers are the source of that power. Swaying personal attitudes towards purchasing gold and diamond rings will successfully change the behaviour of spending habits towards these jewels. The effectiveness of the Blood Diamond campaign is the best example of how information can change personal purchasing habits as well as create formal agreements between international governments and the diamond industry. The success of the No Dirty Gold campaign is still being determined but governments with their partners in industry can take the first steps towards curbing environmental impacts with effective policy, legislation, and enforcement. 26 References 2005 Annual Report NYSE. Newmont the Gold Company. Accessed 28 October, 2006. http://www.newmont.com/en/investor/releases/media/newmont/2005_Annual_Re port.pdf 2005 Health Safety Environment Targets Scorecard. BHP Billiton. 2005(1). Accessed 24 October, 2006. http://sustainability.BHP Billitonilliton.com/2005/repository/performanceGlance/targetsScorecard/targetsS corecard.asp Ayres R., Ayres L. and Råde, I. (2002).The Life Cycle of Copper, its Co-Products and By-Products. Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development, 24. About the Global Compact: The Ten Principles. The United Nations Global Compact. Accessed 28 October, 2006. http://www.unglobalcompact.org/AboutTheGC/TheTenPrinciples/index.html Baumann H., Tillman A.M. (2004) The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Life Cycle Assessment . Studentlitteratur AB. BHP Billiton. A Global Perspective. 2006. BHP Billiton. Company Profile. Accessed 24 October, 2006. www.BHP Billitonilliton.com BHP Billiton. Company Overview. BHP Billiton. Accessed 20 October, 2006 http://www.BHP Billitonilliton.com/bb/aboutUs/companyOverview.jsp BHP Billiton 2003 Health Safety Environment and Community Report. Roberts Environmental Center. Accessed 24 October, 2006. http://www.roberts.cmc.edu/PSI/AutoReports2.asp?ReportNameID=712 BHP Billiton’s Sustainable Development Policy. BHP Billiton. 2005(2). Accessed 24 October, 2006. http://www.BHP Billitonilliton.com/bbContentRepository/docs/SustainableDevelopment/policiesA ndKeyDocuments/HSECPolicy.pdf BHP: The Quiet Deceiver. 2003. Mineral Policy Institute (MPI). Media Background Briefing. Accessed October 16, 2006. http://www.mpi.org.au/companies/BHP Billiton/bhp_deceiver/ Canada: A Diamond Producing Nation. Natural Resources Canada. 2007. Accessed 12 October 2007. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/ms/diam/index_e.htm Canadian Diamonds. Diamond Info. 2007. Accessed 13 January 2007. http://www.diamondinfo.org/canadian-diamonds.html 27 Case Study: Transforming Policy into Sustainable Outcomes. BHP Billiton. 2003. Accessed 20 October, 2006. http://www.banksiafdn.com/page_assets/Case2003_BHP BILLITONilliton.pdf Chang S-Y, Heron A, Kwon J, Maxwell G, Rocca L, Tarajano O. The Global Diamond Industry. Chazen Web Journal of International Business. Fall 2002. Accessed 6 October 2006. http://www2.gsb.columbia.edu/journals/files/chazen/Global_Diamond_Industry.p df. Chevalier, P. Gold. December 2005. Accessed 13 January 2007. http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/ms/pdf/nfo/nfo05/gold_e.pdf Code of Ethics – Commitment. CIBJO The World Jewellery Confederation. Accessed 26 November 2006. http://www.cibjo.org/commitment.html Cohen R. Use of microbes for cost reduction of metal removal from metals and mining industry waste streams. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2006. 14; 1146-1157. Communities Affected by Newmont Speak Out. No Dirty Gold. 27 April 2005. Accessed 22 October, 2006. http://www.nodirtygold.org/newmont_communities.cfm Corporate Governance and Climate Change: Making the Connection. Summary Report. Ceres. March 2006. Corporate Responsibility. Supplier Code of Conduct. Jewellers of America. Accessed 26 November 2006. http://www.jewelers.org/pdf/CorporateResponsibility/SupplierCode.pdf Diavik Mines. Accessed 30 September 2006. http://www.diavik.ca/WCD.htm Dirty Metals. No Dirty Gold. http://www.nodirtygold.org/pubs/DirtyMetals_HR.pdf Accessed 10 January 2007. Durucan S., Korre A., Munoz-Melendez G. (2006). Mining life cycle modeling: a cradleto-gate approach to environmental management in the minerals industry. Journal for Cleaner Production. 14;1057-1070. DJSI STOXX - Supersector Leaders. 2006. DJSI. Accessed 23 October, 2006. http://www.sustainability-index.com/djsi_pdf/Bios06/CBR_BHP_Billiton_06.pdf Dirty Gold Impacts .No Dirty Gold. Accessed 25 September 2006. http://www.nodirtygold.org/dirty_golds_impacts.cfm. 28 Ekati Mines. Accessed 30 September 2006. http://ekati.BHP Billitonilliton.com/default.asp Greenhouse Gas Inventory Data Search. Environment Canada. 2003. Accessed October 8, 2006 from http://www.ec.gc.ca/pdb/ghg/query/index_e.cfm Holloway: Our Social Responsibility. Newmont Mining Company. Accessed 15th January 2007. http://www.newmont.com/en/operations/nthamerica/holloway/social/index.asp Metal Mining Effluent Regulations: Fisheries Act. Canadian Policies and Regulations. (SOR/2002-222). Accessed 13 January 2007. http://www.ec.gc.ca/EnviroRegs/Eng/SearchDetail.cfm?&intReg=174 Mining Certification. World Wildlife Fund. Accessed 27 October, 2006. http://wwf.org.au/ourwork/industry/mining/ The Mining, Minerals, and Sustainable Development (MMSD) Project. International Institute for Environment and Development. Accessed 28 October, 2006. http://www.iied.org/mmsd/what_is_mmsd.html Mining Policy Research Initiative (MPRI). International Development Research Council: Environment and Natural Resource Management. Accessed 27 October, 2006. http://www.idrc.ca/minga/ev-70315-201-1-DO_TOPIC.html Moors E, Mulder K, Vergragt P. Towards Cleaner Production: Barriers and Strategies in the Base Metals Producing Industry. Journal of Cleaner Production. Accessed 2 October 2006. http://nwi.geog.uu.nl/content/files/_1138655421_JCPpaper.pdf. Nedved M, Jansz J. Waste Water Pollution Control in the Australian Mining Industry. Journal of Cleaner Production. 14 (2006); 1118-1120. Newmont the Gold Company. Newmont. Accessed 28 October, 2006. http://www.newmont.com/en/ Paquin M, Sbert C. Toward Effective Enviornmental Compliance and enforcement in Latin America and the Caribbean. UNISFERA: Centre International Centre. November 2004. Accessed 1 December 2006. http://www.unisfera.org/IMG/pdf/New_approaches_to_environmental_protection _vfinale3_ajout_.pdf. 29 Poliquin, Morgan. Mineral Exploration Techniques. Kitco Casey. 2005. Accessed 15 January 2007. http://www.kitcocasey.com/displayMining.php?id=5 Responsible Jewellery Practices. What we stand for. Council for Responsible Jewellery Practices (CRJP). Accessed on October 25, 2006. http://www.responsiblejewellery.com/what.html Sullivan and Sustainability: A Review of 2004 http://www.teckcominco.com/operations/sullivan/sustainability.htm. Accessed January 15th 2007. Tang C, Neves A, Fernandes A, Gracio J, Ali N. A New Elegant Technique for Polishing CVD Diamond Films. Diamond and Related Materials. Aug. 2003. Vol. 12 Issue 8. 1411-1416. Toxic Release Inventory. Chemical Fact Sheets .National Mining Association. Accessed 15 September 2006. http://www.nma.org/pdf/tri/tri_fact_sheets.pdf. Waste Discharge Regulation Implementation Guide. British Columbia Ministry of the Environment. http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/epdiv/env_mgt_act/pdf/wdr_implement_guide.pdf Working on Crown Land: What you should know about Mineral Exploration, Building Construction and Road and Trail Construction. NRCan. 1996. http://www.mnr.gov.on.ca/MNR/csb/news/crown1.html 30 Appendix A – Life Cycle of the Diamond Ring Life Cycle Waste? Exploration Extraction Re-use “A Diamond is Forever” Processing Use Manufacture / Retail 31 Appendix B – BHP Billiton Fig. 1: BHP Billiton’s global operations. (BHP, 2006) Fig. 2: Roberts Environmental Center Pacific Sustainability Index (PSI) results for BHPB. http://www.roberts.cmc.edu/PSI/AutoReports2.asp?ReportNameID=712 32