Abstract of thesis entitled

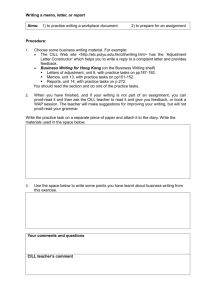

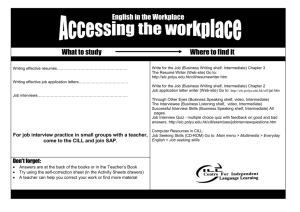

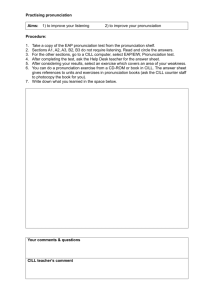

advertisement