Ch 8

advertisement

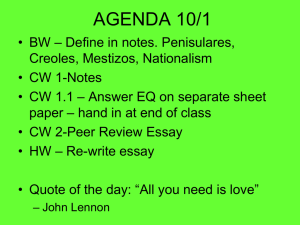

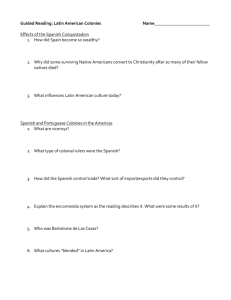

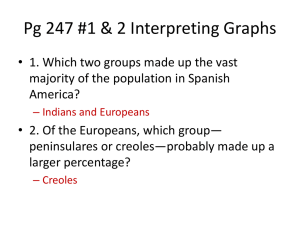

Notes Ch. 8: The Independence of Latin America Pgs. 157-175 I. Introduction. i. Viceroys and intendants introduced improvements and refinements that make life more healthful and attractive. ii. Educational reforms widened the intellectual horizons of creole youth. iii. Growing ranches and haciendas pressure trade barriers. II. Background of the Wars of Independence. a. Creoles and Peninsular Spaniards. i. Conflicts most obvious between creoles and peninsulares. ii. Immigrants had it easier than creoles in social standing. 1. Made creoles bitter because of the discrimination. iii. Spanish merchants financed mines and dominated export-trade. iv. Creoles were refused to acknowledge Spanish heritage. v. Many government officials attempted to improve the quality of life for the creoles to make them happier. vi. Banned books were spread throughout Spanish America. vii. Beginnings of a revolution started to form. 1. United States ships legally and illegally visited SpanishAmerican ports. viii. The French Revolution. 1. Americans printed out their own versions of the French Declaration of the Rights of Man of 1789. 2. Scattered conspiracies formed in the creole aristocracy. 3. French slave revolts inspired black revolutionaries in Latin America, but dampened creole spirits. b. The Causes of Revolution. i. The decline of Spain under Charles IV. 1. Struggles against the French went badly. 2. 1796 Spain became France’s ally. 3. England pursued to block the Atlantic from Spanish use. 4. Napoleon obtained permission to invade Portugal through Spain through Charles IV. 5. Napoleon trapped Charles IV and his son into giving the Spanish thrown to Napoleon’s brother. 6. 1808: Spain raised an insurrection against occupying French troops. 7. 1810: French victory seemed inevitable. ii. Creole victories against the English stimulated large ideas of independence. 1. English fleets attacked Spanish-America. 2. Secret armies attacked invading English soldiers. 3. Hoped Napoleon would invade Spain and grant their independence. iii. A constitution approved in 1812. 1. Limited monarchy. 2. Promised freedom and assembly. 3. Abolished the Inquisition. 4. Allowed peninsular domination and commercial monopoly to remain intact. III. The Liberation of South America. i. Comparisons between the Latin Americans and the American Revolution: 1. Both wanted to throw off the rule of a mother country whose mercantilistic system hindered development. 2. Led by well-educated elites who drew slogans and ideas from the ideological arsenal of the Enlightenment. 3. Both were civil wars in which large elements of the population sided with the mother country. 4. Owed financial success in part to foreign assistance. ii. Differences: 1. Latin America did not have a unified direction or strategy for independence. 2. Latin America lacked strong popular base. iii. Four main centers of the struggle for independence: 1. Two principal theaters of military operations. a. One in the north, one in the south. 2. Two streams of liberations. a. One from Venezuela, one from Argentina. a. Simón Bolívar, the Liberator. i. The symbol and hero of the liberation struggle in northern South America. ii. Grew up in an aristocratic creole family. iii. Read rationalist, materialist classics of the Enlightenment. iv. April 1810: Creole party organized a demonstration that forced the abdication of the captain general. v. Patriots were torn between following Bolívar and postponing the issue. vi. 1811: Venezuela proclaimed its independence and framed a republican constitution. vii. Fighting ensued between the patriots and the royalists. viii. The patriots had trouble with their commander in chief and much of their land was destroyed in the earthquake of 1812. ix. Bolívar issued a Manifesto to the Citizens of New Granada. 1. Called for unity. 2. Condemned the federalist system. 3. Urged the liberation of Venezuela. x. Liberated Caracas from the Spanish forces. xi. 1814: Napoleon fell and Ferdinand took the thrown. 1. Sent Spanish troops to Latin America. xii. Non-republic supporters. 1. Blacks fought for their freedom. 2. Cowboys turned because of the attempt to end the hunting and rounding up of cattle. 3. Semiservile peons were forced to carry identification. 4. Bolívar abandoned Caracas to the cowboys in 1814. xiii. Provinces of Columbia fought against each other and the small central government. xiv. The Spanish army landed in Venezuela. 1. Re-conquered Venezuela. 2. Forced Cartagena to surrender. xv. Bolívar believed Latin America needed a republic to survive. 1. Returned to Venezuela in order to continue his fight. 2. Made his headquarters in Angostura (now Ciudad Bolívar). xvi. Gained the support of the patriots and the llaneros. xvii. 1819: Became a small dictator and urged Venezuela to abolish slavery and distribute land. 1. His constitution had a president with basically royal powers. xviii. The council elected Bolívar president while keeping him in check. xix. The patriot army defeated the royalist army at Bogotá. 1. Was welcomed by the people of New Granada. xx. Ferdinand was forced to give up his reconquest of the colonies. 1. 1821: Last important Spanish army crushed. xxi. The population near Quito revolted against Spanish control. xxii. Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama were free. b. The Southern Liberation Movement and San Martín. i. The liberations of Bolívar and Argentina merged together. ii. 1810: French troops threatened Cádiz. 1. Congresses decided what kind of leader provinces would have. iii. 1814: Montevideo was saved from Spanish invasion. iv. Uruguay did not achieve independence until 1828. 1. Was in a loose federal connection with Buenos Aires. v. Creoles in Paraguay took over Asunción. 1. Proclaimed the independence of Paraguay. vi. The steep terrain of Northern Peru made it hard for communication to ensue between creoles. vii. The Buenos Aires government was having problems. 1. Liberal supporters argued with conservatives. 2. 1813: A national assembly decided to call Argentina the United Provinces of La Plata. 3. 1816: Officially declared independence. viii. José de San Martín joined the revolution when it started. 1. Born in Argentina. 2. Commanded the army of Upper Peru. 3. San Martín offered a plan for total victory. 4. They would distract the Spanish forces at the Andes while other troops descended on the coast. 5. Promised freedom to those who joined his cause. 6. 1817: His army began crossing the Andes. 7. Fought battles that ended the threat to Chile’s Independence. 8. 1820: Sailed for Peru and made threats to the Spanish army which retreated in 1821. 9. Claimed the independence of Peru. ix. San Martín’s troubles in Peru: 1. Lima was very corrupt and he assumed supreme military and civil power in June 1821. 2. Sent a secret mission to Europe to find a monarch for Peru in order to bring stability. x. San Martín met with Bolívar in July 1822. 1. Concerned about the future of Guayaquil. 2. Discussed the topic of the political future of Spanish America. 3. Afterwards San Martín retired abruptly. xi. When San Martín returned to Lima his enemies were rising. 1. September 1822: Resigned as protector and announced his impending departure. 2. Left for Europe in 1823. xii. 1823: San Martín sent men to Lima after the Peruvian congress asked for help. xiii. 1823: Bolívar arrived in Peru. 1. It took almost a year to achieve political stability and unit all of the separate armies. xiv. August 1824: The Spaniards were defeated at the lake of Junín. 1. The last major engagement of war was at Ayacucho in December 1824 where the Spaniards also lost. c. The Achievement of Brazilian Independence. i. Between 1808 and 1822 Brazil’s declaration of independence was mostly bloodless. 1. Started when Portugal tried to tighten political and economic control over the colony. 2. The first large conspiracy started in Minas Gerais in 1788-1789. 3. Major conspiracies: a. 1794: Rio de Janeiro. b. 1798: Bahia. c. 1801 and 1817: Pernambuco. ii. 1807: The French invaded Portugal. 1. Flight of the Portuguese royal family brought benefits to the colony. 2. Brazil’s ports were re-opened. 3. Local industries rose and the Bank of Brazil opened. iii. 1815: Brazil became a kingdom, co-equal with Portugal. 1. Came under the economic domination of England. 2. Portuguese merchants were bitter over the passing of the Lisbon monopoly. iv. The Revolution of 1820 in Portugal. 1. Ended the system of dual monarchy and restored the Portuguese commercial monopoly. 2. A new constitution was drawn up and approved. v. The Portuguese Côrtes tried to abrogate all the liberties and concessions won by Brazil since 1808. 1. September 7 is Independence Day in Brazil after Dom Pedro resisted the will of Portugal and became the constitutional emperor of Brazil. IV. Mexico’s Road to Independence. a. Went from a private quarrel between two elites into a social revolution. b. 1808: Napoleon’s invasion of Spain caused debates and maneuvers between Mexican elites. c. The Mexico City cabildo was a creole stronghold. i. An assembly composed of representatives would govern Mexico until the abdication of Ferdinand VII was voided. ii. The original meaning was to gain power, not independence. d. Peninsular merchants wanted things to stay the same. i. September 1808 merchants led their militia against leading creole supporters. e. The leaders of the creole aristocracy didn’t respond to the peninsular counteroffensive. f. The economic and social conditions of Mexico played a decisive role in the struggle for Independence. i. Agrarian and industrial structure. ii. Most of the population was urban workers, miners, peons, or tenants. iii. Large commercial estates dominated agriculture. iv. Had a putting-out system where merchant-financiers provided families with wool in order for them to turn them into cloth. v. Mining was the most profitable industry in Mexico. g. The Bajío’s economy promoted the growth of workers’ class consciousness and militancy. i. Experienced a decline of wages and living standards. ii. 1808-1809 a great drought and famine struck. h. Creoles were plotting revenge in 1810. i. Most were “marginal elites” or struggling landowners. ii. Denounced by Spanish officials. i. Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla assembled a Mass to rise against Spanish rulers in 1810. i. Lead an insurrection in support of a beloved king treacherously captured and deposed by the Frenchmen. ii. His banner bore the Virgin of Guadalupe. iii. The capture of Guanajuato in 1810 was successful and followed by a massacre of Spaniards. iv. Issued decrees abolishing slavery and tribute. v. Returned communal lands to the indigenous peoples. vi. Hidalgo’s peasants and working-class followers were affected by landlessness, starvation wages, high rents, lack of tenant security, and the monopoly of grain. vii. Refused to attack defenseless people in the capital. viii. His army was getting smaller and fleeing northward. ix. Captured and executed after he tried fleeing to the United States. j. The new Mexican rebel strategy was to exhaust the enemy and undermine its social and economic bases. k. José María Morelos now commanded the revolutionary movement. i. The position of estate tenants and laborers had become increasingly dependent and insecure. ii. Ended slavery, tribute, abolished the rental of indigenous community lands, and abolished the community treasuries. iii. Prohibited all forced labor and forbid the use of racial terms. iv. A brilliant guerrilla leader who did not follow strict discipline, training, and centralized direction. v. Differences in civilian allies made it hard to gain supporters. vi. 1813: Declared Mexico’s independence at Chilpancingo. vii. Suffered several military defeats by 1814. l. Napoleon’s defeat meant soldiers could be sent over in 1814 in order to suppress Spanish-American revolts. i. Morelos drafted a liberal constitution that provided for a republican frame of government in October 1814. ii. In 1815 Morelos was captured and executed in December. m. The Spanish revolutionary movement reached new heights between 1815 and 1820. i. Made no efforts to capture large population centers. ii. Conducted a fluid warfare where small units sacked and destroyed loyalist haciendas and severed communications. iii. Fled when pursued, and popped up somewhere else. iv. 1820: A liberal revolt in Spain forced Ferdinand VII to accept the constitution of 1812 after he raised taxes to pay for the war. n. New constitutional reforms of the Spanish Cortes: i. Abolition of the ecclesiastical military fueros. ii. Antagonized conservative landlords, clergy, army officers, and merchants. iii. Established independence. o. The creole officer, Agustín de Iturbide, offered peace to the rebel leader, Vicente Guerrero. i. Both overcame scattered loyalist resistance. ii. 1821: Iturbide proclaimed Mexico’s independence. iii. Left for England and returned in 1824 only to be shot. p. The contributions of Latin American women: i. Doña Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez saved the revolution from destruction before it had begun. ii. Manuela Saenz, Simón Bolívar’s mistress, saved him from death at the hands of an assassin. iii. Policarpa Salvarrieta was 23 when executed for helping the revolution. iv. María Quiteira de Jesus disguised herself as a man to join the revolutionary army. V. Latin American Independence: A Reckoning. a. Most of Latin America had won its political independence. b. Independence ended the Inquisition. c. Abolished slavery. d. Founded public schools. e. Mestizo and mulatto officers were granted land. f. Individualist ideology undermined indigenous community land tenure. g. Required the division of community land among its members. i. Facilitated the usurpation of the communal lands by creole landlords and helped transform the native peasants into peons or serfs. h. Aristocratic values continued to dominate Latin America society.