10 Trade and growth

advertisement

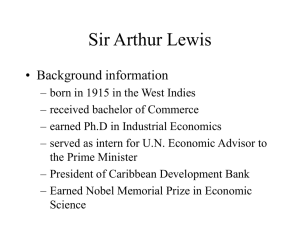

10 Trade and growth Learning objectives By the end of this chapter you should be able to understand: how the combination of increases in factor endowments, improvements in technology and choices of how to spend rising incomes can affect trade; why the source of a country’s growth is important in determining the extent to which some of the benefits of growth are offset by a decline in its terms of trade; why developing countries that rely upon primary product exports have been especially vulnerable to volatile export earnings and terms of trade; how import substitution policies attempt to avoid such terms-of-trade declines but risk creating permanent inefficiencies; why more open trade policies have been an important part of the success of economies that have grown more raidly; how growth may cause a negative externality such as pollution, and differing government regulations to reduce pollution may affect the location of production and pattern of trade. Growth offers the hope of rising standards of living. Faster growth in developing 1 countries may allow them to close the gap between the higher levels of income per capita in industrial countries and their own level. Although international organizations such as the World Bank and the United Nations seek to promote growth in the developing world, not all countries are sanguine about that outcome. Europeans and Americans worry that the impressive growth of China and India over the past decade poses a threat to them, anticipating ever greater competition internationally. That concern might be alternatively phrased: As countries become more similar, does that reduce the gains from trading for some? Some developing countries do not see themselves competing with the EU or the US, and instead they worry that expansion of their export sectors may result in little benefit to them, because of the adverse effect on prices in international markets. Whether either of these concerns is relevant depends upon the sources of growth, not just the fact that GDP per capita has risen. One goal of this chapter is to demonstrate when circumstances warrant these worries and when a more optimistic outlook is appropriate. Not only is growth likely to affect trade, but economists and politicians have long debated how trade will affect a country’s growth prospects. In the second part of this chapter, we address this issue with special attention to developing countries. In the 1950s and 1960s many of the latter rejected the view that there are mutual gains from trade. Instead, they viewed the international trading system as likely to impoverish developing countries further. Newly independent countries wanted to reject links to their colonial past and the market system. Instead, they aimed for less dependency and more selfsufficiency. In the 1970s, many developing countries argued for a radical transformation of the trading system under the rubric of the New International Economic Order, with 2 the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) being the primary forum for the advancement of these ideas. Primary-product prices were to be increased and stabilized, special trade preferences were to be created for developing countries, foreign aid was to be sharply increased, and a variety of other reforms were to be put in place to help poor countries. Although industrial countries granted some trade preferences to developing countries, most other parts of that agenda were not adopted. The sense of pessimism that permeated much of the earlier discussion and the dependency theory on which it rested (i.e. developing countries face such poor prospects that they have no chance of growing under existing market mechanisms) was less pervasive, because some previously underdeveloped countries experienced rapid economic growth without a remaking of the international economic order. Faith in import substitution industrialization shifted to support for export-led growth, as represented by the lessons that the World Bank drew from the experience of newly industrialized countries (NICs) in Asia. What elements of this alternative approach are necessary to generate sustained growth or whether the star performers in the developing world have followed a different set of policies is another of the ongoing controversies we address in this chapter. Finally, we consider another aspect of economic growth, a possible negative externality that result from greater pollution and damage to the environment. How countries chose to deal with the way their increased production affects environmental quality within their borders can affect patterns of international trade, too. Some observers worry that a quest for growth at any cost will result in a race to the bottom in terms of environmental 3 standards and a shift of the dirtiest industries to the poorest countries. Not all negative externalities are confined within the borders of producing countries, as the international debate over global warming forces us to recognize. How countries move beyond the Kyoto Protocol to the Climate Change Convention, which expires in 2012, again has important implications for the pattern of international production and trade. Building blocks to determine the effects of economic growth on trade Countries’ patterns of trade clearly change over time. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the United States primarily exported tobacco, then cotton, and later foodstuffs. By the twentieth century it became a major exporter of manufactured goods, but in the first decade of the twenty-first century, it instead is a net exporter of services. For an even more rapid transformation in the post-war period, consider Korea’s shift from initially being an exporter of primary materials, next becoming a dominant provider of apparel and footwear, and most recently excelling in steel, electronics, and semiconductors. Our previous chapters have presented more than one explanation for the pattern of trade we might observe, and those alternative perspectives again are relevant here. We begin our analysis by reviewing the effect of changing factor endowments and changing technology in a world with perfectly competitive firms. We also address the role of domestic demand conditions. We first consider the implications for the volume of trade of a small country that cannot affect prices internationally, and then allow for additional issues that arise when prices do change. 4 [Figure 10.1 about here] The neutral case of proportional growth and demand If all factor inputs increase by the same proportion and constant returns to scale hold, then a country’s production-possibility curve uniformly shifts out by that same proportion along any ray from the origin. That situation is shown in Figure 10.1, where the proportional increase from C1 to C2 is the same as the proportional increase from F1 to F2 or P to P’. Alternatively, such a shift in the production-possibility curve can result from an increase in the productivity of all factor inputs in all sectors by the same percentage; more output can be obtained from the same inputs. In terms of the growth of developing countries, the World Bank notes that increases in the availability of factor inputs have been more important than increases in factor productivity, an issue discussed further in Box 10.1. [Box 10.1 about here] At unchanged terms of trade, Country A will continue to produce the two commodities in the same proportions as in the initial equilibrium, as indicated by the points P and P′ on the vector OP′. The effects on Country A’s consumption and its volume of trade depend on its pattern of demand, as shown by its community indifference curves. If Country A chooses to consume food and cloth in the same proportions as before, both its imports of food and its exports of cloth will rise in proportion to the increase in output. In this case, where Country A’s income elasticity of demand for both goods is unity, its consumption points (Q and Q′) will lie on the vector OQ′. Consumption of both goods increases in proportion to economic growth. 5 The effect of a bias in demand Figure 10.2 summarizes possible outcomes for the case of proportional growth in factor supplies but a biased demand response to growth. Initially, production occurs at P, consumption at Q, and the trade triangle SPQ represents cloth exports, SP, and food imports, SQ. At unchanged international prices, growth results in the new production point Q’. Various effects on trade are possible, depending upon demand conditions. The neutral expansion path, with income elasticity of unity for both goods, is along the vector OQ′: consumption of both goods rises in proportion to income growth. [Figure 10.2 near here] If the demand for food rises more than in proportion to income (income elasticity of demand for food is greater than one), then the expansion path will be steeper than QQ′, falling in the angle GQQ′, and exports will increase by a greater proportion than output. Growth is then biased toward trade. If the demand for food rises less than in proportion to income (income elasticity less than one), then the expansion path will be less steep than QQ′, falling in the angle Q′QH, and exports will increase by a smaller proportion than output, or they may even decline. The latter case results if the new demand for food is below point K along the barter line P’G, where K is determined from drawing QK parallel to PP’. Growth is biased against trade in that case. The greater the income elasticity of demand for the export good, the more likely the bias against trade. The effect of a bias in supply 6 As shown in Chapter 3 for the factor proportions model, an increase in one factor results in an outward shift in the production-possibility curve that is biased toward the commodity that uses intensively the factor whose supply increases. For the two-good model, an increase in the labor force results in greater output of the labor-intensive good and a reduction in the output of the capital-intensive good at unchanged prices of output. If the country initially is labor abundant, then the increase in the labor force results in a particularly large increase in exports, a case of ultra-protrade-biased growth using the taxonomy of H.G. Johnson.1 Conversely, growth in a country’s relatively scarce factor makes the country more similar to the rest of the world and results in an expansion of the import-competing sector and a decline in the export sector, an ultra-antitrade-biased effect. If a labor-abundant country experiences a large enough expansion of its capital stock, it can become a capital-abundant country, and its comparative advantage will shift from labor-intensive goods to capital-intensive goods. The implications of that sort of change are discussed in Box 10.2 with respect to changes in export patterns for Malaysia and China. [Box 10.2 about here] For industrialized countries, increases in factor productivity have been more important sources of rising output than increases in factor supplies. Changes in factor productivity are more complicated to analyze, however, because wages and returns to capital can change even though prices of goods remain unchanged. Recall from chapter 3 that many economists believe changes in productivity that create more demand for skilled labor are a key reason for a widening wage gap in industrialized countries. Therefore, it is worth introducing another analytical technique to enable us to represent these various 7 consequences of productivity changes. [Box 10.3 near here] Findlay and Grubert address these issues using the Lerner diagram shown in Figure 10.4.2 Isoquants for steel and textiles are shown which represent a unit of output. At the wagerental ratio represented by the budget constraint C0C0, steel producers will choose to use the capital-labor ratio given along the ray OS0, while textile producers will choose the capital-labor ratio given along the ray OT0. Because both isoquants are tangent to the same budget constraint, that means that costs and prices of the two goods are identical. How much of each good will be produced? That depends upon the country’s factor endowment, but instead of the Edgeworth box used in earlier chapters, here we represent that situation differently by including the endowment at point E and then drawing rays from it that are parallel to OS0 and OT0. EB intersects OT0 at B and EA intersects OS0 at A. For both factors to be fully employed at the given wage-rental ratio, the economy produces OA of steel and OB of textiles. [Figure 10.4 about here] Now consider the effect of a change in factor productivity in this diagram. If capital and labor requirements fall by the same proportion in the textile sector only, this saving of inputs allows the unit isoquant for textiles to shift inward. Because the percentage effects on capital and labor in the textile industry are the same, the new isoquant has the same slope along the ray OT0 as was observed initially. The lower cost of producing textiles, 8 however, gives firms an incentive to expand output, and as they do so in a labor-intensive industry, the wage rate rises relative to the rental return to capital. The new budget line that represents the same value of output in each industry, C1C1, is tangent to the new textile isoquant and the initial steel isoquant at T1 and S1, respectively. The higher wagerental ratio gives producers in both sectors an incentive to use a higher ratio of capital to labor. We now have two new rays indicating the best capital-labor ratios to use in production after the technical change occurs, and we can again complete the parallelogram from point E to determine how output changes. To keep the diagram from becoming too cluttered, we do not show that new solution, but you should be able to confirm that textile production increases while steel output declines. In this case, the shift in the productionpossibility curve is quite similar to what we found above for an increase in the factor endowment. A biased trade effect occurs, with more trade occurring if the country is labor abundant but less trade occurring if the country is capital abundant. If there were neutral technical improvements in the production of steel, the shift of the productionpossibility curve at unchanged output prices would give increased steel output and reduced textile output. Such unambiguous predictions need not follow for other types of technical change, such as labor-using technical change in the textile industry; the starting point for that analysis is an inward shift of the textile isoquant that gives a lower optimal capital-labor ratio at the initial wage-rental ratio. But, you now have a framework to apply in determining what type of shift in the production-possibility curve will occur and what output combination we should expect to observe at the same output prices. 9 The discussion above treats the change in technology as exogenously given, independent of any effort by the country to create and apply this new technology. This rather extreme assumption may be relevant for some developing countries, but economists have more generally considered how growth might be regarded as endogenous. Robert Feenstra provides a useful overview of models where productivity and the rate of growth depends upon the variety of intermediate inputs available, which yield the result that free trade may result in smaller countries growing at a slower rate than larger countries.3 That outcome is more likely the less the extent of any spillover of knowledge of better technology from large countries to small countries. We do not elaborate that line of inquiry, but note that there are several implications of growth for trade and trade for growth that extend beyond the basic concepts presented here. Large countries and changes in the terms of trade If growth leads to a decrease in the quantity of exports a country supplies at the initial price ratio, and the country is large enough to affect prices internationally, it benefits from an improvement in its terms of trade. Conversely, if growth causes an increase in the quantity of exports supplied, the country’s producers must accept a lower price for their exports. Such a decline in its terms of trade reduces the benefits derived from economic growth. Also, if countries such as China and India effectively catch up with industrial countries and have less need to import capital intensive, high-tech goods, the terms of trade of industrial countries that export those goods will decline. 10 These predictions follow from the two-good model presented in Chapters 2 and 3, where growth occurs due to an increase in the output of the two existing goods. If we consider growth in the context of Krugman’s model from Chapter 4, where production of more varieties by monopolistically competitive firms occurs, it does not necessarily follow that growth in a country’s exports will cause a decline in its terms of trade. Economists have examined the contrasting role of growth on the intensive margin (more exports of the same product) versus the extensive margin (exports of more varieties of goods) to assess which characterization is more relevant. David Hummels and Peter Klenow carry out such an analysis and make a further distinction to consider changes in the quality of existing goods.4 From 1995 trade data they conclude that larger countries export more than smaller countries, with 62 percent of this difference is due to the extensive margin and 38 percent to the intensive margin. While the increase in varieties is not as great as the Krugman model predicts, the authors also find that large countries do not rely upon lower prices to sell additional varieties. High income countries tend to export higher priced (higher quality) goods within a product category. How these relationships may have changed over time is an ongoing research agenda. Immiserizing growth We backtrack to consider a more traditional concern in the two-good model for the case of a country’s export biased growth. In that case it is even possible that the loss from an adverse change in the terms of trade will exceed the gain from increased capacity, thus leaving the country worse off than before. This rather extreme case, called “immiserizing 11 growth,” has attracted much attention, especially in connection with complaints of developing countries over their prospects in world trade. Consider the changes in production and consumption for Country A shown in Figure 10.5. Because this argument has most often been raised in the context of developingcountry exports of primary products to industrialized countries for manufactured products, we label the axes accordingly. Initially, A is producing at P0 and exporting primary products in exchange for manufactures at the terms-of-trade ratio indicated by the slope of P0C0. Through trade it can reach the welfare level represented by indifference curve i0. Consumption is at C0. [Figure 10.5 about here] As a result of growth in the supply of factors used in the production of primary products, A’s production-possibility curve shifts to the right, from AB to HK. It now offers larger quantities of exports, and its terms of trade decline as shown by the flatter slope of P1C1. At this exchange ratio, A continues to export primary products, but it can only reach the lower indifference curve, i1. Thus, growth in capacity has reduced economic welfare. This outcome is more pronounced when an export-biased production effect is combined with a strong preference in Country A to spend additional income on manufactured goods. Growth results in a large increase in the quantity of exports supplied, and if import demand in the rest of the world is inelastic, there is a substantial decline in the relative price of primary goods. Country A receives a smaller quantity of manufactured goods in exchange for a larger quantity of primary-product exports. Although the theoretical possibility clearly exists, actual cases of immiserizing growth 12 are especially hard to prove. It requires a country large enough to have a significant effect on the world price of its export, and one whose growth is strongly biased toward exports. For example, the demand for imports of sugar may be inelastic, but the import demand for sugar from Mexico is likely to be elastic. Mexican sugar is a very good substitute for sugar from other countries, and because Mexico accounts for a small share of the market it can attract customers away from other suppliers. Some economists believe that groups of developing countries have sometimes suffered losses as a result of their joint expansion of capacity to produce certain export commodities. In that case, a single country no longer increases its market share at the expense of others, and all face a lower price. Although this outcome is just a possibility, countries have adopted policies motivated by the worry that it will occur, which leads us to consider alternative trade policies. Trade policies in developing countries Developing countries have diverse perspectives over the way the world trading system might change in order to be a more positive factor in achieving their goals with respect to economic growth. Therefore, the discussion of trade patterns for developing countries as a whole, presented in Box 10.4, provides a useful starting point but is admittedly an incomplete overview. Similarly, a comparison of terms of trade movements over the 1965-2006 period, given in Figure 10.6 for some major country groupings, shows important distinctions must be made among developing countries. The experience of oil exporters is quite different from developing non-oil exporters. The latter group has experienced a decline in its terms of trade since 1980, as have industrial countries, but for the developing non-oil exporters both the downward trend and volatility around that trend 13 are greater. The record for oil exporters is quite volatile, but not closely matched to producers of other primary products. [Box 10.4 about here] [Figure 10.6 near here] To evaluate these patterns more carefully, we begin by considering those countries that are reliant upon primary product exports. We then examine the experience of countries that have come to rely more upon manufactured exports and pay special attention to the policy debate over the best way to accomplish this shift. Primary-product exporters and price volatility Many of the poorest developing countries typically export large amounts of a small number of products, often primary products, which has made their export revenues quite volatile. Many OPEC members derive more than 80 percent of their export revenues from oil and gas. Consequently those countries faced severe declines in their export receipts in the 1980s and 1990s, and then a bonanza of revenue in the following ten years. A country with highly concentrated exports is analogous to a family with all of its net worth invested in the common stocks of one or two companies in a single industry: the family’s investment income is likely to be very unstable. For a sample of the least developed countries, Table 10.4 reports the large role played by their top three exports, and their consequent vulnerability to volatility and declines in those prices. Various World Bank and UNCTAD studies document greater volatility of primary product prices than prices of manufactures.5 14 [Table 10.4 near here] What explains this greater volatility? One reason may be that the prices of many primary products are determined in highly competitive auction markets, such as the London Metal Exchange, whereas manufactured-goods prices are determined in more oligopolistic markets. Highly competitive markets are known to have more price variability than do oligopolistic markets. Another explanation is that elasticities of supply and demand are lower for primary products than for manufactured goods. A developing country that has grown a certain amount of a perishable commodity is willing to sell it for whatever price is available, because in the short run it has few alternatives; its supply is very inelastic. If the price elasticity of demand for these products is also very low, because they have relatively few substitutes, the likelihood of large price swings is greater. A shift of either the supply or the demand curve causes a far larger price change than will occur when the demand and supply curves are more elastic. International commodity-price stabilization programs are often suggested as a solution to this problem of price volatility. If both importers and exporters agree on a target or “normal” price and if the industrialized consuming countries are willing to provide initial financing, the stabilization fund purchases and stores the commodity whenever the market price falls below the target, thereby pushing it back up. When market prices rise above the target, the program sells the commodity from previously accumulated stocks, pushing the price back down.6 This approach sounds attractive, but such programs have a poor track record. Consumers 15 and producers seldom agree on the target price, and when such prices have been set, they are almost always too high. The fund has to continually purchase the commodity and soon runs out of money. Production quotas are frequently proposed as a way to support prices without continual commodity purchases by the fund, but every exporting country wants a large quota. If quotas are agreed upon, countries frequently cheat by producing above their quotas and trying to sell this output secretly. Programs in coffee, coca, tin, and sugar proved unsuccessful. Furthermore, stabilizing commodity prices is not synonymous with stabilizing export revenues. If price shocks primarily originate on the demand side, the two goals may coincide, but if supply shocks (weather, crop diseases) are more typical, stabilizing prices with a buffer stock program such as that described above is actually likely to destabilize export incomes. In years of small harvests, an offsetting rise in prices is not allowed, while in years of large harvests, a high price is paid anyway. Volatility of export earnings is problematic for several reasons. The ability of countries to maintain their standard of living suffers when earnings fall. Countries are likely to reduce their investment as incomes and foreign exchange earnings decline, which adversely affects their long-run growth. The high earnings in boom-years may attract opportunistic politicians, who gain considerable personal wealth rather than use the funds effectively to cushion periods of price decline. As suggested in the Chapter 3 discussion of a possible resource curse, democratic succession becomes less likely and armed conflict more likely as well. A long-term answer to the problem of revenue volatility is product diversification. 16 Countries that develop new or nontraditional export markets benefit from the fact that prices in these markets are not likely to change in the same direction all the time and the elasticity of demand for the individual goods is likely to be larger for a new entrant who accounts for a small share of the market. Primary product producers and deteriorating terms of trade Over the past few decades, the larger problem for primary-product exporters has been not price volatility, but price declines. Since 1980 prices of nonfuel commodities relative to manufactured goods exported by developed countries have fallen by 45 percent. 7 Such a negative relationship was predicted by Raul Prebisch and by Hans Singer over 50 years ago.8 The Prebisch–Singer hypothesis followed from these authors’ observation of the change in Britain’s terms of trade over the period from 1876 to 1947. They noted that technical progress in manufacturing did not create an expected benefit for primaryproduct producers in the form of improved terms of trade. Rather, the opposite occurred. One possible explanation was that technological improvements in manufacturing simply allowed unionized workers in those countries to receive higher wages, or monopolists to increase profit margins, without passing this benefit on as lower prices to buyers. In contrast, workers who produced primary products could not avoid pressure to accept wage cuts in cyclical downturns. Another concern was that demand for primary commodities tended not to be income 17 elastic. Foods and beverage markets have always been threatened by Engel’s law, which states that the income elasticity of demand for such products is less than one. This idea is named after Ernst Engel, a nineteenth-century economist who found data supporting this conclusion. Poor people spend a high percentage of their incomes on food, but this percentage steadily declines as incomes rise. This means that markets for food and beverage items do not expand as rapidly as the world economy unless the distribution of income shifts to lower income groups. Technical progress in manufacturing also has tended to reduce demand for raw materials. That scenario is particularly relevant in explaining the experience in the 1980s. Prices of metals, fuels, and fibers might have been expected to decline in the early 1980s when virtually all of the industrialized world was in a recession, which sharply reduced the demand for these products. The lack of price increases during the strong macroeconomic recovery of the mid- and late 1980s, however, came as something of a surprise. Technical breakthroughs, which produced substitutes for some primary products, were one cause of this outcome. Fiber optics replaced copper in the telephone industry. Steel was replaced by plastic, aluminum, and other products in various uses. Natural fibers were supplanted by artificial fibers, and technical changes reduced the amount of oil consumed in many industries. Over the longer run, the situation is more difficult to characterize. Economists have progressively assembled better data to carry out such analysis. Also, they have more carefully tested whether the pattern of prices represents random variation without a clear 18 trend and whether there have been clear breaks in any trend. A tentative summary of the evidence for the twentieth century is that no clear trend exists, and a break in the series likely occurred in 1921.9 Further research may well yield different conclusions. Alternative trade policies and the transition to greater manufactured output The governments of many developing countries concluded some time ago that reliance on expanding output and exports of their traditional primary products was not a promising development strategy. This realization led to a search for alternatives. Two broad policy trends that have emerged are commonly referred to as import substitution and export-led growth. Import substitution During the 1950–70 period, the governments of many developing countries adopted policies to minimize their reliance on trade. Instead of promoting more output of primary export commodities, they imposed tariffs and provided other assistance to encourage the growth of local industries, which could produce substitutes for products that they imported. This inward-looking strategy meant that declining primary-product prices would be less threatening, because large export revenues were no longer needed to pay for imports. The export sector could be ignored or even taxed, a strategy that promoted the shift of resources out of primary production. This policy orientation meant that developing countries had little interest in participating in GATT, as noted in Chapter 9. The models presented in Chapters 2 and 3 of this book suggest that this retreat from trade may result in large efficiency losses to the economy. Scarce resources are invested 19 precisely where they will be used less efficiently. Labor-abundant countries, with very limited investment budgets, allocate large amounts of money to capital-intensive industries that provide very little employment. The factor endowments theory suggests they should be doing just the opposite: spread their limited capital stocks thinly across labor-intensive industries, where comparative advantages exist, thereby maximizing employment opportunities for an abundant labor force and generating export revenues. The extremes of this policy are reflected in Balassa’s measures of the effective rate of protection for consumer durables in several developing countries during the early 1960s: Brazil 285 percent, Chile 123 percent, Mexico 85 percent, Malaysia –5 percent, Pakistan 510 percent, and the Philippines 81 percent.10 This policy orientation fell from favour when financial crises severely limited the ability of countries to borrow the capital that was necessary to expand capital-intensive industries and pay for oil imports. Also, policy makers could not ignore the success of more open economies. Although most economists reject the view that protection is good for economic growth, the historical record indicates that this approach can succeed if it is pursued for a limited period of time in carefully chosen sectors. The infant-industry argument for protection, discussed in Chapter 6, suggests that if a country has a potential comparative advantage in a product, protection may allow that industry to expand, learn, and bring its costs down. The World Bank studies of the East Asian miracle note that some countries did intervene in the market, but they were successful in “pulling the plug” on those industries that were unsuccessful, such as chemicals in Korea and heavy industry in Malaysia. Developing some system of accountability and providing 20 protection for only a limited time avoids the danger of perpetuating mistakes if the infant industry never matures. Success was most likely initially when the industries for which protection was provided were relatively labor-intensive. Both Korea and Taiwan used this approach, but as the favored industries became exporters, protection was not the key to their expansion. Import substitution was an expensive failure in countries such as India that relied upon it for decades and extended it to highly capital-intensive industries. This policy is particularly disastrous if applied to industries whose products are inputs for sectors that should export. As a consequence, many negative effective rates of protection are created in the export sector. A country may have a comparative advantage, for example in textiles, but a comparative disadvantage in dyestuffs and textile machinery. If such a country protects inefficient manufacturers of dyestuffs and textile machinery, it will destroy its export potential in cloth. The prices of dyestuffs and machinery will be so high that the country cannot compete in world textile markets, despite an abundance of inexpensive labor. Many developing countries protect inefficient steel industries, and thereby lose the opportunity to export products that use steel; recall the example of the Indonesian bicycle industry in Chapter 5. For many years Brazil was determined to develop a local computer industry and therefore prohibited the importation of foreign computers. Because the local computers that were available in Brazil were expensive and outdated, that harmed every export industry that relied upon computers. Free-trade zones and duty drawbacks 21 Even if policy makers decide to abandon a policy of import substitution, such a move may be difficult to accomplish politically, given powerful established interests in protected industries. A piecemeal strategy that many developing countries have pursued is to establish a special enterprise zone or free-trade zone, which may allow a country to develop export industries that require inputs that the country protects and produces inefficiently. This protection is eliminated for firms who produce in the zone, where they can import the necessary inputs at world prices, as long as they sell their output in foreign markets. If the finished goods are sold locally, tariffs apply. Locating the zone at a seaport or airport often is most economically efficient and administratively feasible, to reduce transport costs for inputs and exports and to prevent the diversion of assembled goods into the domestic market. An additional benefit from this strategy can be realized if the final export market treats the output more favourably by imposing an import tariff only on the value added in the zone, not on the value of the intermediate inputs used in its assembly. Such a relationship between Mexico and the US was one of the motives for the establishment of the maquiladora assembly industry along the northern border of Mexico in the 1960s. The intermediate inputs had to come from the US, however, to receive this treatment. US trade provisions under the African Growth and Oppportunity Act of 2000 did not impose the requirement that US cloth be used to stitch garments to be sold in the US, and as a result Lesotho’s apparel exports to the US took off. Similar benefits are available under programs that allow imports to come into the country under a bond, which will be returned once the producer shows proof that the imports have 22 been used in goods that have been exported. Alternatively, some countries operate duty drawback schemes that allow producers to claim a refund for any tariffs paid on inputs, once they demonstrate that those imports have been used in assembled exports. Administering any of these programs can become complicated, but they do represent an intermediate step between a policy of free trade and protection of the home market Export-led growth The World Bank book East Asian Miracle states the 1990’s consensus position that an export-led growth approach to trade policy is more promising than import substitution.11 As early as the 1970s, studies were published showing that developing countries that pursued an export-led approach experienced far more rapid economic growth than did countries with protectionist policies.12 The original Four Tigers (Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and South Korea) were the subject of most of this early research, but the second wave of Asian NICs (Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and China) has also been very successful in pursuing export markets. India, Mexico, and Brazil could be added as recent converts to this approach. These countries have been successful exporting laborintensive manufactured goods, as Heckscher–Ohlin would predict, but more capital- and skill-intensive industries are beginning to prosper in these markets. Better education has proven to be an important prerequisite to benefit from the spillovers of technology from more advanced countries. Outsourcing of services to India has drawn much attention, because it, too, has been characterized by progressively more advanced processes being shifted there. Note that this export promotion strategy rests upon diversification and expansion of 23 nontraditional exports. Countries blessed with fertile land do not automatically exit from all agricultural industries, but they consider alternatives to the narrow set of traditional commodities produced. For example, Malaysia successfully reduced its dependence on rubber production by shifting to palm-oil production. The governments of some of the Asian Tigers actively intervened in the market by providing favourable financing and direct export subsidies, policies that today would draw greater scrutiny from the WTO. Even in the absence of those measures, an exportled policy does not imply no role for the government. Governments need to promote physical infrastructure, such as ports, roads, electricity and telephone service. Basic health and education ensure a more capable labor force. A clear set of legal rights and its consistent application and enforcement encourages long-term investments. The Chapter 5 discussion of effective rates of protection demonstrates why high tariffs on intermediate inputs are counterproductive. That disadvantage has been reduced substantially but in 1997 still penalized agricultural processing, labor-intensive manufacturing, and capitalintensive manufacturing in Brazil, China, and India with rates that ranged from -17 percent to -54 percent.13 In that same vein, tax and regulatory policies that raise prices of key inputs likewise need to be limited. For countries whose major comparative advantage still rests on cheap unskilled labor, a significant problem for those hoping to export goods that require unskilled labor intensively is that industrialized countries continue to maintain peak protection in such industries. To the extent that earlier waves of NICs have successfully penetrated such markets and account for a large share of sales, then expansion by newcomers may come 24 at the expense of the earlier exporters. For example, Chinese, Vietnamese and Indonesian shoe production has largely displaced Korean and Taiwanese exports. In the apparel and textile sector, however, industrial countries still have substantial domestic production, which will face further competitive pressure as more developing countries become integrated into the world trading system. Additional Perspectives The World Bank’s 2005 book, Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform, does not prescribe such a precise set of policies as was the case a decade earlier. Even though the goals of stable macroeconomic conditions, market-oriented incentives and an outward orientation are still recognized as highly desirable, the authors do not maintain that there is a single way to move toward achieving them. Also, it advocates a focus on what are the binding constraints on growth, rather than push governments to dissipate political capital and administrative capability on achieving best practice across the board. This more modest agenda also recognizes that precisely how and how much greater exports contribute to faster growth remains an active area of research that is less definitive than the earlier consensus suggested. With respect to the goal of a more open economy, Dani Rodrik gives an example of this more flexible approach: best practice may call for reducing import tariffs, but if there is no alternative source of tax revenue to finance government expenditure, then a more realistic step toward openness would be to establish an export processing zone.14 To implement this more incremental strategy, Rodrik suggests a diagnostic approach to 25 determine what constraints are binding, which in some cases may call for priority attention to trade policy but in other cases not. The chapter case study contains other insights regarding the nature of growth in China and the reasons for its success. Growth and environmental externalities Just as economists treat natural resources as a source of growth, even when such resources are exhaustible, environmental quality may be treated in this same way. Countries may choose to degrade their environmental quality in order to achieve additional economic output or growth. Those who must live and work in a more polluted environment bear additional costs, due to poorer health, less productivity on the job, or less enjoyment of their surroundings, for example. These are negative externalities that producing firms need not consider in the absence of government action or an organized coalition of those affected. Countries are likely to differ in the way they deal with such externalities, and few are likely to choose no pollution at all as the optimal policy. Economists consider the efficient level of pollution as one where the extra benefit from being free of another unit of pollution just equals the extra cost from cleaning up that unit of pollution. That situation is shown in Figure 10.7, where the marginal benefit curve and the marginal cost curve intersect. [Figure 10.7 about here] If all countries placed the same value on a cleaner environment and faced the same cleanup costs, which would be shown by identical marginal benefit and marginal cost curves for all countries, then unilateral action by each country would result in the same clean-up standards everywhere. In that situation, there would be no tendency for runaway 26 plants to leave a country that imposed its own optimal pollution control standard, because the plant would be subject to the same controls in any alternative location. The existence of the externality, and the government’s effort to make the offending plant recognize the cost it imposes on others, would not alter trade patterns, because relative costs of production would be affected identically in all countries. More typically, there are differences in the way countries value a cleaner environment, or there are differences in the clean-up costs they face. The marginal benefit and marginal cost curves will not be identical in each country, and on economic grounds it is then in the interest of countries to choose different pollution control standards. The value that countries place on environmental clean-up is especially likely to diverge when one of the countries is an industrialized country and the other is a developing country. Environmental quality tends to be a luxury good; as income rises, demand for environmental quality rises to a greater extent. Based on this relationship we predict that richer countries will impose stricter standards and enforce them more stringently. Also, growth in richer countries may be due to increases in human capital, which is used intensively in clean rather than dirty industries, whereas growth in poor countries may be due to increases in physical capital, which is used intensively in dirty industries. At the same time, though, production per person is much greater in high-income countries, which tends to generate more pollution and raise the cost of maintaining a given level of environmental quality. Initial research in this area did not examine these various effects separately. Instead, it simply the following question: as a country’s income rises, does its environmental quality rise? 27 In answering this question by examining how several measures of pollution varied with income across 42 countries, Grossman and Krueger spawned a major new research area.15 In most cases, they found that an inverted U-shaped relationship exists: pollution rises as output rises up to a certain threshold, and then declines. This relationship has been called the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC), because it is similar to what Simon Kuznets conjectured for inequality in the distribution of income as countries became richer. Subsequent research has assessed how robust this relationship is by including changes over time within a country, not simply differences across countries. Copeland and Taylor review those developments, especially as they provide insight about the relevant structural relationships that must underlie the EKC, such as what are the sources of growth in a country, how strong are consumer preferences for environmental quality at different levels of income, and are there economies of scale in pollution abatement activities.16 While economists continue to refine this approach, the implication that countries will choose different standards of environmental quality is clear. Do these different policy choices, and the opportunity to pollute more in developing countries, mean that there is a significant cost incentive to locate more dirty industries in the developing world? Casual empiricists might point to the change between 1965 and 1988 in the share of exports accounted for by dirty industries (steel, nonferrous metals, industrial chemicals, petroleum refining, and non-metallic mining): it declined from 20 percent to 16 percent for OECD countries but increased in Eastern Europe and Latin America.17 Over that same time period the stringency of OECD regulations to reduce pollution rose. At first glance those two trends seem to support the concern that 28 developing countries will become a dumping ground for dirty activity. On further reflection, however, analysts need to consider what other factors changed over this same interval that may explain changing export patterns, too. Copeland and Taylor suggest that changes in factor endowments are one plausible alternative, which is especially relevant if the relative endowments of capital, used intensively in dirty industries, grew rapidly in developing countries. In addition, more capital in developing countries would contribute to a reduction in the relative price of dirty goods, whereas more stringent pollution controls in the OECD would raise the price of dirty goods. No clear trend in the relative prices of dirty goods occurs over this period, a signal that we should not restrict our attention to environmental regulations in explaining the shift in production that occurred. Early studies did not find that more stringent environmental policy led countries to import more dirty goods, a result that implied a rejection of the pollution haven effect. Those studies assumed that environmental policies were chosen irrespective of the level of imports, however. If governments set policies taking into account the level of imports, with more imports resulting in weaker domestic policies, then the estimated effect of policy will be understated. Copeland and Taylor cite studies on industrial location within the US that find a major response to clean air regulations, but they note that comparable international evidence is severely limited by the lack of data for many developing countries. The tragedy of the commons 29 The environmental externalities considered thus far are assumed to have a negative effect strictly in the country where production occurs. That framework ignores production and consumption that can alter conditions across borders and even globally. Global warming is one such example. Addressing that problem is particularly difficult, because no single country can expect benefits large enough to warrant unilateral action. Global climate conditions can be regarded as a common property resource, and the disincentive to take action that would avoid global warming results in the tragedy of the commons, as summarized by the following example from Garret Hardin.18 We expect privately owned property to be maintained and preserved because it is in the interests of the owner to do so, but commonly owned property will be badly overused because no individual has an incentive to protect it. If, for example, 1,000 people are grazing excessive numbers of sheep on land that is commonly owned, a single farmer has no incentive to reduce the number of animals he puts on the land. All of the sheep owners may understand that the land is being badly overgrazed, but if any single farmer reduces the number of his sheep, nothing will be accomplished because 999 farmers are still overgrazing. As a result, nobody acts to protect the commonly owned grazing land, which may ultimately be ruined. Global warming and trade The EU has taken a leadership role in advocating that action be taken to curb emissions of greenhouse gases under the precautionary principle: although all the scientific relationships that explain global warming still are not clearly understood, to fail to take 30 action now would be imprudent and likely cause even higher costs of environmental clean-up or adaptation in the future. The Kyoto Protocol to the Climate Change Convention agreed to in December 1997 called for industrialized countries to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from their 1990 levels by the year 2012.19 Reductions were to be 8 percent in Europe, 7 percent in the United States, and 6 percent in Japan and Canada, while Russia was to stabilize its emissions. The ratification of the agreement by Russia in 2004 satisfied the trigger condition (developed countries representing at least 55 percent of the group’s carbon dioxide emissions in 1990 must join) for the agreement to come into effect in February, 2005. As of 2007, neither Australia nor the United States had joined. But, because the agreement will expire in 2012, much debate now centers on what type of successor agreement can be reached. Three key questions underlying this debate are how much clean up is warranted, how quickly should it occur and who should do the cleaning up. The Stern review of the economics of climate change, prepared for the Chancellor of the Exchequer in October 2006, implies that maintaining the current rate of greenhouse gas emissions will likely result in an increase in average temperature of 2 degrees Celsius by 2050, with more severe impacts in the future if there are irreversible changes in climate conditions, such as the melting of the Greenland ice sheet, the drying up of the Amazon Rainforest, or a shift of the Atlantic Gulf Stream. To avoid a reduction of per capita consumption of five to twenty percent, the report advocates immediate efforts to reduce emissions so that the concentration of gases that leads to the 2 degree increase in temperature will not be exceeded. Critics note that this case rests on the choice of a very low discount rate, 0.1 31 percent, which gives great weight to events happening in the next century. Those individuals advocate a more gradual increase in the stringency of any emission reductions.20 While this aspect of the situation is unresolved, the gainers and losers from global warming are less uncertain. Losers will be tropical countries dependent on agriculture, forestry, and economic activity in coastal plains. Small countries with only a single climate zone are particularly vulnerable, as are islands with little elevation above sea level. Table 10.5 gives a summary of these effects for larger groups of countries. Russia and other northern countries may gain from global warming that unlocks frozen northlands and opens new navigation routes, and over the next few decades world agricultural output may even rise if higher concentrations of CO2 have a positive fertilizing effect.21 [Table 10.5 near here] With respect to who should pay for the clean up, the Kyoto agreement requires no reductions in greenhouse gas emissions from developing countries, although industrial countries can meet a portion of their commitment by jointly implementing projects with former communist transition economies and by carrying out clean development projects in developing countries. Developing countries regard the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as the responsibility of industrial countries that accounted for much of that accumulation through their progressively higher energy usage over the past two centuries. Denying developing countries their opportunity to industrialize on the grounds of modern environmental awareness and eco-imperialism is rejected as the basis of an 32 agreement that will lead to an unjust distribution of benefits and costs. Designers of a new agreement are particularly constrained by the self interest of two of the countries shown in Table 10.5, the United States and China. Because the US accounted for 23.4 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in 1990 and China is projected to account for 24.5 percent in 2030, the largest current and future emitters both are likely to face large net costs, from the standpoint of national self interest, if they make binding commitments to reduce emissions.22 Perhaps public perceptions will change sufficiently in these countries to overcome this arithmetic. If a new agreement does not involve participation by developing countries, the location of high-emission activities there will be even greater than would be predicted from their continued industrialization. [Chapter 10 case study here] Summary of key concepts 1 Neutral growth, where production of all goods rises by the same percentage, will result in the same percentage increase in export supply if consumers continue to consume all goods in the same proportion. 2 If growth at constant prices results in a disproportionately large increase in output of the export good, and consumers wish to spend the extra income primarily on the import good, then the increase in the country’s export supply will be especially large. 3 If a country is large enough to affect world prices, growth that results in a large increase in the supply of exports may result in a sufficiently large decline in the relative price of the export good to leave the country worse off. This special case of immiserizing growth is more likely to occur when foreign import demand for this 33 good is quite inelastic. 4 Many developing countries remain highly dependent on the exportation of one or two primary products. Producers of primary products have been especially concerned over the declining prices of these goods compared to manufactures. 5 To avoid over-reliance on primary exports, many countries in the 1950s and 1960s adopted a policy of import substitution to shift resources into manufactures. Although this policy promoted industrialization, it became quite costly when countries chose to permanently protect capital-intensive industries that produced key inputs into other goods where the country had a comparative advantage. 6 Export-led growth has been a successful strategy for countries that diversify into nontraditional exports where they have a long-run comparative advantage in production and where they face a more elastic foreign demand. Although these exports were labor-intensive initially, as countries have acquired more physical and human capital, their pattern of comparative advantage has shifted to more technologically advanced goods. 7 Different countries have adopted different policies to deal with the negative externality of greater pollution as output expands. Assessing whether production in dirty industries will relocate to countries with less stringent environmental standards requires that we control on production shifts that would occur due to changing factor endowments. Questions for study and review 34 1 A capital abundant country increases its capital stock by 5 percent, all else constant. How does that change affect its production and volume of trade? Does its terms of trade change in a way that creates a further benefit for the country? 2 A labor abundant country increases its capital stock by 5 percent, all else constant. How does that change affect its production and volume of trade? Does its terms of trade change in a way that creates a further benefit for the country? 3 If a large economy grows at the same rate as the rest of the world, why are its demand preferences important in predicting whether its terms of trade will improve or not? 4 Use the Lerner diagram to demonstrate the expected shift in the production possibility curve of a country that experiences labor-using technical progress in its capitalintensive sector. How is the capital-labor ratio in each industry affected? If the country is large and labor-abundant, how will its terms of trade be affected? 5 Why may a price stabilization pact not be successful in reducing the volatility of the export earnings of primary product producers, even when it successfully stabilizes prices? What challenges do pacts face in successfully stabilizing prices? 6 Falling computer prices do not seem to be a source of hardship in industrial countries that exported them in the 1980s and 1990s. Why are falling prices of primary commodities in LDCs a serious problem? 35 7 Vietnam increased its share of the world coffee market from 1 percent to 15 percent over a 10 year period. Was this expansion of a primary product export likely to result in immiserizing growth for Vietnam? When is that concern most relevant? 8 When many countries pursued policies of import substitution, their growth rates were high in the 1960s and 1970s but fell in the 1980s. Is that evidence of the success of these policies or the limits of these policies? 9 “LDC tariffs intended to promote an industry may in fact inhibit development of the LDCs’ most efficient industries.” Explain how this could happen. 10 Why is it difficult for a country to pursue import substitution and export promotion at the same time? What policies are called for under each strategy? 11 Is there an economic rationale for countries to adopt different pollution control standards? Under what circumstances will their choices have little influence on the location of production and trade internationally? 12 The EU established an Emission Trading Scheme in 2005 that applied to large installations like power plants. The price for being allowed to emit a ton of CO2 fell in 2006 and 2007 because national governments distributed so many allowances that little clean up was required. If those allowances are reduced in the future, how do you expect that to affect EU production and trade? Suggested further reading 36 In addition to the studies cited in the text, consider two monographs by Nobel-prizewinning economists cited for their contributions to economic development: Lewis, Arthur William, The Evolution of the International Economic Order, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978. Schultz, Theodore William, Investing in People: The Economics of Population Quality, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1981. For an overview of post-war academic perspectives on trade and development, see Krueger, Ann, “Trade Policies in Developing Countries,” Handbook of International Economics, Volume I, eds, R. Jones and P. Kenen, New York: Elsevier Science Publishers, 1984, pp. 519-569. For an algebraic treatment of the effect of changes in factor endowments and technology on trade see Raveendra Batra, Studies in the Pure Theory of International Trade, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1973. For accessible articles that debate the importance of protection in allowing the industrial countries to grow, see Douglas Irwin, "Tariffs and Growth in Late Nineteenth Century America," The World Economy, January 2001, pp. 15-30. Ha-Joon Chang, "Kicking Away the Ladder - Tariffs and Economic Development," Challenge, Sept./Oct. 2002, pp. 63-97. For more extensive evidence on the way various successful Asian economies intervened in their economies, see 37 Robert Wade, Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of the Government in East Asian Industrialization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990. Alice Amsden, The Rise of “the Rest”, New York: Oxford University Press, 2001 For a broader discussion of environmental externalities and policies adopted to deal with them see Todd Sandler, Global Challenges: An Approach to Environmental, Political and Economic Problems (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997) Notes 1 Harry Johnson, “Effects of Changes in Comparative Costs as Influenced by Technical Change,” in R. Harrod and D. Hague, eds., International Trade in a Developing World, London: Macmillan, 1963, Chapter 4. 2 Ronald Findlay and Harry Grubert, “Factor Intensities, Technological Progress, and the Terms of Trade,” Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, Vol. 11, No. 1. (Feb., 1959), pp. 111-121. The Lerner diagram appeared in published form as A. P. Lerner, “Factor Prices and International Trade,” Economica (new series), 19, no. 73, February 1952, pp. 1-15. The theoretical framework assumes constant returns to scale and no factor intensity reversal (textiles are labor intensive at all wage-rental ratios), conditions that were imposed in the analysis of Chapter 3. 3 Robert Feenstra, Advanced International Trade, Theory and Evidence, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004, Chapter 10 synthesizes many contributions in this area, with special attention to Gene Grossman and Elhanan Helpman, Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991. 4 David Hummels and Peter Klenow, “The Variety and Quality of a Nation’s Exports,” American Economic Review 95, no. 3 (June, 2005), pp. 704-723 38 5 World Bank, Global Economic Prospects and the Developing Countries (Washington, DC: World Bank, 1994), pp. 52, and UNCTAD, Least Developed Countries Report 2002, p. 142. 6 For a thorough analysis of commodity-price stabilization programs, see J. Behrman, Development, the International Economic Order, and Commodity Agreements (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1978). 7 UNCTAD, op. cit., p. 138. 8 Raul Prebisch, “The Economic Development of Latin America and Its Principal Problems,” Economic Bulletin for Latin America, 7 (1950), pp. 1-22, and Hans Singer, “The Distribution of Gains between Investing and Borrowing Countries, American Economic Review 40 (1950), pp. 473-485. 9 J. Cuddington, R.Ludema and S. Jayasuriya, “Prebisch-Singer Redux,” US International Trade Commission, Working Paper, June 2002. 10 Bela Balassa, The Structure of Protection in Developing Countries (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971). 11 Other indications of support for this interpretation are P. Chow, “Causality between Export Growth and Industrial Development: Empirical Evidence for the NICs,” Journal of Development Economics 26, no. 1, June 1987, pp. 55–63; and S. Edwards, “Openness, Trade Liberalization, and Growth in Developing Countries,” Journal of Economic Literature, September 1993, pp. 1358–93. The term Washington consensus was coined by John Williamson to refer to the apparent consensus among the IMF, the World Bank and the U.S. Treasury Department, all located in Washington, D.C., over the appropriate policies to promote stability and growth in developing countries. For his retrospective evaluation of this consensus, see http://www.iie.com/publications/papers/williamson0904-2.pdf. 12 In addition to numerous country studies, there are three volumes that synthesize and summarize the overall results of this research: Ian Little, T. Scitovsky, and M. Scott, Industry and Trade in Some Developing Countries: A Comparative Study (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970); Jagdish Bhagwati, Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development: Anatomy and Consequences of Exchange Control Regimes (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976); and Anne Krueger, Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development: Liberalization Attempts and Consequences (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976). A later survey of the literature on trade policy and development can 39 be found in Oli Havrylyshyn, “Trade Policy and Productivity Gains in Developing Countries,” World Bank Research Observer, January 1990, pp. 1–24. 13 World Bank, Global Economic Prospects, 2004, p. 77. 14 Dani Rodrik, “Goodbye Washington Consensus, Heloo Washington Confusion? A Review of the World Bank’s Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform,” Journal of Economic Literature 64, no. 4 (December 2006), 973-987. 15 Gene Grossman and Alan Krueger, “Environmental Impacts of a North American Free Trade Agreement,” in Peter M. Garber, ed., The Mexico–US Free Trade Agreement (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 199), pp. 13–56. Gene Grossman and Alan Kruger, “Economic Growth and the Environment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110, no. 2, pp. 353–77. For more recent estimates, see S. Dasgupta, B. Laplante, H. Wang and D. Wheeler, “Confronting the Environmental Kuznets curve,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2002, pp. 147–68. 16 Brian Copeland and Scott Taylor, “Trade, Growth, and the Environment,” Journal of Economic Literature 62, no. 1 (March 2004), pp. 7-71 is a useful summary of this approach and other developments in this literature. 17 Patrick Low and Alexander Yeats, “Do Dirty Industries Migrate?” in International Trade and the Environment, ed., Patrick Low, Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 1992, pp. 89-104. 18 Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science, December 1968 19 For an accessible, pre-Kyoto discussion of the potential costs of global warming, the costs of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and various policy implications, see the papers in the Journal of Economic Perspectives 1993 symposium on global climate change. For more complete information on the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and its Kyoto Protocol, as well as further analysis by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, see updates from http://unfccc.int . 20 William Nordhaus,“A Review of the Stern Review on the Economics of Global Warming,” Journal of Economic Literature 45, no. 3 (September 2007), pp. 686-702. 21 For various approaches to determining the economic damages countries will face from global warming, see William Nordhaus and Joseph Boyer, Warming the World: Economic Modeling of Global Warming, 40 Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000, William Cline, Global Warming and Agriculture: Impact Estimates by Country, Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics, 2007, and P. Buys, U. Deichmann, C. Meisner, T. That, and D. Wheeler, “Country Stakes in Climate Change Negotiations: Two Dimensions of Vulnerability,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 43000, August 2007. 22 For an elaboration of these issues, see Cass Sundstein, “Montreal versus Kyoto: A Tale of Two Protocols,” AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies, Working Paper 06-17, August 2006. 41