bone-tired(bone-tired) - Universitat de Barcelona

advertisement

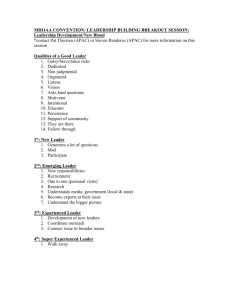

Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . I. INITIAL EVALUATION. CHECKING PREVIOUS KNOWLEDGE. EVALUACIÓN INICIAL O DIAGNÓSTICA.1 1. Which is your favorite season? a. b. c. d. Spring Summer Fall Winter 2. ¿What do you associate fall with? a. Death c. Beginning of academic year e. Other (please specify) _______ b. Sales d. Football/ Soccer league 3. Would you consider any of the following personalities a hero? If so, which one? a. Julius Caesar b. Homer c. Hercules d. Nero e. Socrates 4. Moby Dick, Apocalypse Now, El Quijote, Hamlet, True Grit, El desorden de tu nombre, El quadern gris, La soledad del manager, El mirall trencat, Encerrado con un solo juguete, No Country for Old Men. Choose one of these or another you remember whose title a. b. c. d. makes you curious includes the name of the main character suggests what happens in the work allows for various possible interpretations Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -1- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 5. Haver you ever seen a wild boar? Was it alone? How many were there? What was your reaction? 6. In ancient Rome during the republic, leaders were chose by the citizens. Who did not have the right to vote when Rom was a republic? a. women b. slaves c. women and slaves Figura 1 Fuente: http://laboratoriodesociales.wordpress.com/ 7. The Greeks would uproot the olive trees in the fields of their enemies when they defeated them. a. I believe that is true b. I don’t believe it’s true c. I don’t know 8. Early on in the story characteristics associated with cats, dogs and snakes are mentioned. Think up a multiple choice question to check prior knowledge on this subject. ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ a. ________________________________________________________ b. ________________________________________________________ c. ________________________________________________________ Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -2- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 9. The story mentions Plato and Seneca. Think up a multiple choice question to check prior knowledge of Greek and Roman philosophers. ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ a. ____________________________________________________ b. ____________________________________________________ c. ____________________________________________________ Plato Seneca 10. The story mentions a Caesar without specifying which one. So the action must take place after the time of the republic. Think up a multiple choice question to check prior knowledge about the figure of Caesar. You can use the pictures below if you like. ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ a. ____________________________________________________ b. ____________________________________________________ c. ____________________________________________________ Julius Caesar Tiberius Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac Claudius -3- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 11. Working in groups, select one of the terms from the list below for brainstorming. You have half a minute to write down as many keywords as you can associated with the term selected. a. ROME b. MARRIAGE c. FRIENDSHIP d. AGE e. DEATH f. POWER g. SLAVERY h. ELECTIONS i. REPUBLIC 12. After reading a story in class, I prefer being able to talk about with my classmates I prefer having the possibility of writing down notes individually I prefer _______________________________ (write in your own option here) 13. Think up a multiple choice question to check prior knowledge about ancient Rome or whether history or ancient history was one of your favourite subjects in school. ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -4- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . II. INTRODUCING KEY TERMS (a) Praetorian guard http://buscon.rae.es/draeI/SrvltConsulta?TIPO_BUS=3&LEMA=pretoriano (b) Wild Boar (c) Caesar http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/César_(título) Propose other key terms and find definitions for them or provide a picture to make them easier to understand. Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -5- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . III. PRE-TASKS 1. Why do you think the story is called “The Autumn of the Heroes”? Because the action takes place in autumn Because it tells about the final stage in the life of certain heroes. Because autumn is a sad season For all of the reasons above Other (please specify):_________________________ 2. If you have ever woken up in the middle of the night and not been able to get back to sleep, what did you think about to go to sleep again? family death a pleasant memory food the future Other (please specify)_______________________ 3. Read the first paragraphs of “The Autumn of the Heroes”. What do you think Lucius Severus was thinking about just before he fell asleep again? family death a pleasant memory food the future Other (please specify)___________________________ When Lucius Severus awoke that night in the dark there was a moment when he did not even know who he was. But it passed. When his eyes had grown accustomed to the dark he could distinguish the silhouette of the woman at his side, but he felt so alone he did not even want to embrace her. “That’s the time old men tend to die,” his doctor had told him once, years before. “The body is wise, Lucius, much wiser than you or I. As you get older, you’ll begin to wake up at that hour more often, perhaps just to confirm that you’re still alive.” And the doctor had laughed. He was a thin, bony old man, with sunken cheeks and foul smelling breath. So used to dealing with death that he was more friend to it than to the living. A few days before, Lucius had gone out, as was his custom at that time of year, to hunt boar. And today, if dawn ever came, he would eat the animal he had killed. He remembered the smell of the woods, the crackle of dead leaves underfoot, the noise of the dogs, wild with eagerness and fear, the harsh sound of his own breath as he ran, the men waiting, leaving it to him to give the death blow with his spear. It was a formidable beast this year, clever, far cleverer, evidently, than the dogs, killing two of them before they cornered him. Had he been afraid at some point? Perhaps. But he knew his slaves would ensure nothing happened to him. “Who are you trying to convince,” his cousin Alexander had asked him when he returned home, bone tired2, filthy but smiling, “your young wife or yourself?” Poor Alexander. Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -6- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . And as he imagined the taste and smell of the stewed boar that he would eat in a few hours, Lucius Severus went back to sleep. 3. Read the first paragraphs of “The Autumn of the Heroes” again. Keeping in mind the title of the story, what do you think is going to happen? a. Lucius Severus dies of a heart attack b. Lucius Severus discovers his wife is cheating on him c. Lucius Severus goes back to sleep and dreams the story of his life d. Lucius Severus gets up and prepares to fight in a battle e. Lucius Severus gets up and prepares to die f. Propose an alternative: Lucius Severus ________________ 4. Read the following quotes from different characters in the story and indicate your agreement with them from 1 to 6. Discuss the possible contexts in which they might take place. … We…let ourselves be taken in by virtuosity and ostentation. We have lost all taste for simplicity Totally agree……………………………… Totally disagree talk about things we know nothing about, which are the only things worth talking about Totally agree……………………………… Totally disagree A man who thinks must, from time to time, confront reality, in order to think it once again. Totally agree……………………………… Totally disagree Because wine is the only thing that can, if only for a moment, make time stop. Totally agree……………………………… Totally disagree I think less and less… and… the less I think, the better things go for me. Totally agree……………………………… Totally disagree Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -7- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 5. Since the Pou de la Neu prize is a literary and gastronomic prize and the story takes place in the time of the Roman Empire, which of the following dishes do you think might appear in the story? Which would not appear? Wild boar stew. Country style hare. Salad with tomato and soft cheese. Leek salad with onion, mint, thyme, parsley and cheese. Lentils with coriander with vinegar and honey. 6. En las pre-tareas de lectura presentadas se ha optado por centrarse en (a) el título (b) el comienzo del relato (los dos primeros párrafos) (c) citas, afirmaciones o sentencias breves entresacadas del texto (d) contenidos temáticos y no de forma (a) En la pregunta 1 se pide al lector discutir el título ¿por qué cree que se ha optado por ofrecer respuestas múltiples en lugar de haber formulado una pregunta abierta? ¿Por qué cree que es relevante centrarse en el título de los textos como estrategia para facilitar la comprensión de los mismos? (b) En las preguntas 2 y 3 se ha optado por desvelar el comienzo del relato (los dos primeros párrafos) conectándolo con las experiencias previas del lector y pidiendo que éste prediga el posible desenlace de la historia. ¿Por qué es importante hacer que el lector tome partido, prediga, piense, adivine un posible final? ¿Por qué es importante, no sólo en las primeras fases, comprobar e indagar las experiencias previas de los aprendices y sus conocimientos previos? (c) La pregunta 4 pide al lector que se pronuncie sobre sentencias cortas ¿Cómo de cognitivamente exigentes son cada una de las sentencias seleccionadas? ¿Por qué puede ser de ayuda anticipar algunas ideas complejas? ¿Por qué cree que se da la opción a que el lector determine su grado de conformidad? (d) La pregunta 5 se centra en contenidos temáticos como la gastronomía de la época y pide al lector que adivine qué posibles recetas contiene el relato. ¿Qué relevancia tiene el juego, la competición y la utilización de la deducción, inferencia, predicción, deducción o simplemente el hecho de pedir que se adivine, en base a conocimientos previos, para facilitar la comprensión lectora? 7. Escoja alguna otra sentencia corta entresacada literalmente o adaptándola del texto y diseñe una pregunta de respuesta múltiple de pre-lectura sobre la misma. 8. Escoja otros posibles contenidos temáticos que aparezcan en el curso del relato y diseñe una actividad de pre-tarea de lectura para facilitar la comprensión lectora. (Puede Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -8- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . reciclar alguna de las ideas utilizadas en las tareas de evaluación diagnóstica: el imperio, los césares, los filósofos griegos, etc.) IV.WHILE-READING TASKS Diseñe el esquema de la estructura del relato. Complete el esquema que el autor ha esbozado 1. Introducción: La noche. Lucio Severo no puede conciliar el sueño La muerte La caza del jabalí 2. La mañana Despedida de de su mujer Paseo por el campo Encuentro con el porquero 3. La cocina Encuentro con Lavinia, la vieja esclava cocinera Recuerdos de niñez V. CHECKING COMPREHENSION. POST-READING TASKS 1. After having read the story, which of the following best explains the title? The main character, Lucius Severus, has a heroic attitude when confronting his destiny. The title reflects the sadness of the lives of the characters. The title allows for different interpretations suggested by the idea of autumn: sadness, age, resignation, death. (Fill in your own idea) ________________________ ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________ 2. Find paragraphs in which there are indications that Lucius Severus know they are going to come for him. Please note down the lines. 3. In the story there are many moments of nostalgia. Find three paragraphs that show the nostalgia Lucius Severus feels. 4. Read the following paragraph He had been afraid that she would be bored in the country, but that had not happened. They had been happy, perhaps too happy. They kissed and stood for a moment looking at one another. Gazing at the fine lines around her eyes, it occurred to Lucius Severus that he would never see her face grow old, and he felt a sadness come over him that he had to make an effort to conceal… Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac -9- Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . Why does Lucius Severus think that he and his wife had been perhaps too happy? Why do you think this phrase is indicative of what is going to happen? 5. Compare Lucius Severus and his cousin Alexander using the terms below. Put the characteristics they have in common in the part where the two circles intersect. hunter restrained moderate philosopher homosexual intelligent ironic melancholy soldier pessimist bachelor 6. What does the passage below, particularly the dialogue, tell us about the Praetorian officer and Lucius Severus’s cousin Alexander? The officer entered with his helmet under his arm. He had left his escort outside with their horses. Later it would be necessary to feed all of them, find them somewhere to sleep, try to avoid their raping some unwary slave girl. The officer was a Praetorian, no longer young, with tired eyes and a face the colour and texture of old leather. He glanced at the table out of the corner of his eye, then spoke. “I’m looking for Lucius Severus, by order of the Senate.” “You mean of Caesar,” Alexander corrected. “I say what they tell me I’m supposed to say,” the officer replied. “And you don’t think,” Alexander asked, filling a glass of wine and handing it to him. “I think less and less,” the officer answered, accepting the glass, “and, you know, the less I think, the better things go for me.” “I can see you are a man with good judgement,” Alexander said. “Do you like boar, I wonder?” Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 10 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 8. En parejas, identifiquen los momentos de mayor intensidad emocional. ¿Han enumerado los mismos? 9. En parejas diseñen una tarea más de comprensión lectora 10. Expliciten qué finalidad perseguían con la misma. Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 11 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . VI. FOLLOW-UP TASKS 1. Which of the following adjectives would you select to describe the Praetorian officer and Alexander after reading the dialogue above? Which would you not use to describe either of them? Would you add any other terms to describe them? friendly, arrogant, cynical, cruel, cultured, polite, hospitable, ignorant, firm, intelligent, ironical, loyal, obedient, proud, pedantic, perceptive, haughty Alexander Praetorian 2. Tradicionalmente, las actividades de producción de output escrito suelen reservarse para el final. Proponga una actividad de escritura. Aquí tiene algunas sugerencias. (a) Contraste la actitud de Lucio Severo con la de un cristino en las mismas circunstancias. (b) Describa la relación entre Julia y Lucio Severo los últimos años de su vida en común (c ) Narre una de las aventuras amorosas de Alejandro 3. Tradicionalmente, las actividades finales que acompañan un texto suelen centrarse en aspectos formales de gramática o vocabulario. Diseñe una actividad que se explote algún aspecto de las formas lingüísticas 4. Por último, en las actividades de consolidación o ampliación, suelen incluirse otros textos complementarios sobre los contenidos temáticos. Seleccione sus propias fuentes o utilice las suministradas a continuación para diseñar alguna tarea de consolidación o explotación de los contenidos temáticos no lingüísticos Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 12 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . Figura 2 Fuente: http://laboratoriodesociales.wordpress.com/2008/06/01/repaso-ut8-historia-de-roma/ Figure 3 Césares Also see https://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/ Ejemplos de evaluación incial disponibles en https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxuYXZlc3RlcmVzYXxneDo5NDk4OGRj OTU3ZGZlODg Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 13 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 1.¿Por qué cree que las preguntas 1 y 2 de la evaluación inicial sobre la estación preferida y las asociaciones del otoño no implica espera que haya una respuesta correcta entre las múltiples ofrecidas y se limitan a pedir la opinión del aprendiz? 2.¿Había reparado en las palabras en negrilla de la evaluación inicial? ¿Qué palabras fueron seleccionadas, palabras gramaticales como conjunciones y preposiciones o palabras léxicas como sustantivos? ¿Coincide con las palabras clave seleccionadas? ¿Sugeriría algún cambio? 3.¿Cuál cree que es la finalidad de la pregunta 3 que reproducida a continuación? ¿En qué cree que puede ayudar a la comprensión lectora? Moby Dick, Apocalypsis Now, El Quijote, Hamlet, Pepa Niebla, El desorden de tu nombre, La soledad del manager, Encerrado con un solo juguete. Escoja una obra entre las mencionadas arriba o de su propia elección cuyo título le picase la curiosidad llevase el nombre del protagonista sugiera lo que sucede en la obra sea susceptible de múltiples interpretaciones Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 14 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 4.¿Cuántas de las preguntas de la evaluación inicial se centran en contenidos temáticos y cuantas en contenidos lingüísticos? ¿Por qué cree que se ha escogido esa proporción? 5.Si quisiese incluir una pregunta en la evaluación inicial sobre aspectos formales, de contenidos lingüísticos ¿qué pregunta se le ocurre podría ser relevante? 6.¿Qué importancia cree que juegan las imáges seleccionadas y los diagramas incluídos en facilitar la comprensión del input? 7.¿Cual es la finalidad de la pregunta 12 de la evaluación inicial sobre las preferencias tras la lectura de un relato? ¿A qué objetivo de la evaluación diagnóstica apunta? 8. En el segundo apartado se opta por presentar términos claves que van desde expresiones como “en el otoño de la vida’, ‘pretoriano’ o ‘jabalina’. ¿Por qué cree que se puede resultar conveniente explicar el significado de términos clave? ¿Qué diferencia observa entre la selección de términos y expresiones clave y la presentación de vocabulario? 9.¿Por qué puede resultar conveniente en tareas dirigidas a aprendices de segundas lenguas o lenguas extranjeras incluir el formato de respuestas de múltiple elección? 10.La mayoría de las pre-tareas de lectura como las de comprensión lectora parten de fragmentos del propio texto o bien analizan el título del mismo. ¿Cree que en su mayoría son preguntas que buscan fomentar el pensamiento crítico (high-order-thinking skills) o bien se trata de preguntas que buscan fiscalizar la comprensión literal, pormenorizada del texto? Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 15 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . THE AUTUMN OF THE HEROES1 David C. Hall When Lucius Severus awoke3 that night in the dark there was a moment when he did not even know who he was. But it passed. When his eyes had grown accustomed to the dark he could distinguish the silhouette of the woman at his side, but he felt so alone he did not even want to embrace her. “That’s the time old men tend to die,” his doctor had told him once, years before. “The body is wise, Lucius, much wiser than you or I. As you get older, you’ll begin to wake up at that hour more often, perhaps just to confirm that you’re still alive.” And the doctor had laughed. He was a thin, bony old man, with sunken cheeks4 and foul2 smelling breath. So used to dealing with death that he was more friend to it than to the living. A few days before, Lucius had gone out, as was his custom at that time of year, to hunt boar. And today, if dawn ever came, he would eat the animal he had killed. He remembered the smell of the woods, the crackle of dead leaves underfoot, the noise of the dogs, wild with eagerness and fear, the harsh sound of his own breath as he ran, the men waiting, leaving it to him to give the death blow with his spear. It was a formidable beast this year, clever, far cleverer, evidently, than the dogs, killing two of them before they cornered him. Had he been afraid at some point? Perhaps. But he knew his slaves would ensure nothing happened to him. “Who are you trying to convince,” his cousin Alexander had asked him when he returned home, bone tired5, filthy but smiling, “your young wife or yourself?” Poor Alexander. And as he imagined the taste and smell of the stewed boar that he would eat in a few hours, Lucius Severus went back to sleep. In the morning he saw off his wife, who was going to visit her sister, who lived half a day’s journey away. She had put off the trip a number of times, for one reason or another, until he encouraged her to go before the cold weather set in. He had been afraid that she would be bored in the country, but that had not happened. They had been happy, perhaps too happy. They kissed and stood for a moment looking at one another. Gazing at the fine lines around her eyes, it occurred to Lucius Severus that he would never see her face grow old, and he felt a sadness come over him that he had to make an effort to conceal. After that, when the cart that was © David C. Hall (2010) The Autumn of the Heroes, English version of El Otoño de los Héroes. Premio Pou de la Neu 2008. V.2. 1 2 foul adjective /faʊl/ adj • extremely unpleasant Those toilets smell foul! I've had a foul day at work. Why are you in such a foul mood this morning? What foul weather! • describes speech or other language that is offensive, rude or shocking There's too much foul language on TV these days. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/foul_1 Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 16 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . carrying her had disappeared into the woods and he had waved at her one last time, he went for a walk around the estate. It was a clear day, with a cool wind and blue sky, and Lucius was surprised to find that he could still find a sharp, intense pleasure in the smell of the morning. He gazed6 at the olive trees, heavy with fruit, and felt a pride in them, thinking of the barrels of oil that would come from the press that winter. He remembered how the Greeks, when at war, would uproot the olive trees in their enemies’ fields. How cruel, he thought, and how astute. Like tearing the soul from the earth. Then, as he continued along the path that descended gently from the house and down into the forest of pines and oak trees, he noticed a cat following him. It was tigerstriped, black on grey, and small, probably not yet full grown. It stopped when Lucius looked at it and stood watching him, with curiosity but no sign of fear. There were always cats roaming the house and the terrain around it, and they were tolerated because they kept the vermin3 down, but they were normally skittish4, since the slaves were apt to kick them out of the way. Lucius smiled and the cat ran on ahead of him for a while, then stopped suddenly, looking at something on the ground in front of it. Lucius saw a dun5 brown snake, not very big, stopped still, like the cat. It was an ordinary looking snake, undoubtedly harmless, but the cat, Lucius thought, had no reason to know that. Abruptly, the snake began to move, sliding smoothly over the dust. When it had almost completely disappeared into the weeds7 at the edge of the path, leaving no more than an inch or two of tail to be seen, the cat sprung8 forward, throwing out one paw9 in attack, but the snake was already gone. Then the cat turned with an air of satisfaction, proud of itself, as if to say it had done all it could. What a clown, Lucius said to himself, smiling. A dog would probably have attacked the snake at once without thinking. The dog is a noble animal, he thought, remembering the two he had lost on his last hunt. The cat, on the other hand, calculates its possibilities, and is brave when it suits its purposes. But who would win if the two, cat and dog, were to compete to be lords of the world? It seemed clear enough. He remembered then how when he was a child his grandmother had told him that seeing a snake in the morning would bring bad luck, bad luck that could only be avoided by cutting off the snake’s head and throwing its body into the fire. Just one of the old lady’s silly superstitions, he thought, since in spite of her wealth and family she had been a countrywoman at heart, but for an instant he felt a chill, as if a shadow had fallen across the sun. When he raised his head the cat was gone. He saw a slave coming out of the pigsty10 down below, whistled 11to him, and the man came running as fast as he could. His body was deformed, probably from birth, hunchbacked6 and bandy-legged7, so that Vermin adjective: alimañas feminine plural, bichos masculine plural, sabandijas feminine plural http://www.merriamwebster.com/spanish/vermin 3 4 Skittish adjective: : asustadizo, nervioso http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/skittish 5 dun adjective /dʌn/ adj of a greyish-brown colour (Definition of dun adjective from the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary at http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/dun 6 Hunchbacked adjective: jorobado, giboso http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/hunchbacked Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 17 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . when he moved it was as if he were edging sideways, like a crab. His nose was flat, the mouth large, toothless and, apparently, always open. He bowed12 and was about to kiss Lucius’s hand, but his master restrained him with a gesture. “Have you finished feeding them?” he asked, nodding in the direction of the pigsty. The swineherd8 moved his head, his lips seemed about to shape a word, but nothing came out of his mouth. “You see that pine?” Lucius asked him, pointing to a tree on the top of a hill not far away. “Go up there and watch. If you see someone coming along the road, come and tell me at once. Do you understand?” He saw the panic in the slave’s eyes and it occurred to him that though he had spent his whole life on the estate, the swineherd had probably never crossed the threshold13 of the big house. “Don’t worry. I’ll leave word with Paulus to let you in.” Lucius went back to the house then and sat down with his overseer9. It promised to be, as always, a long and boring conversation. Three years had gone by since Lucius had moved to the country and taken charge of the estate, and the overseer was still afraid that he would discover that he had been stealing from him for years, something which Lucius, on his part, had never doubted. The overseer was a sly, spiteful14 and ignorant creature, and some years before Lucius had amused himself for a few weeks with his wife, who was good looking though not particularly clever, knowing that she would end up telling her husband about it and that he would have to swallow it in silence. Lucius had almost forgotten all that by this time, but the overseer almost certainly had not. When he had finished with the overseer, he could no longer resist the temptation to go down to the kitchen, because the aroma of cooking had by then reached almost every corner of the house. The young slave girls went suddenly quiet and blushed15 when he came in, but Lavinia, the cook, laughed, and her old face turned into a map full of wrinkles16. “What is your highness 10doing here?” she demanded. “Do I need a reason to come and see you, lovely as you are?” The old woman laughed again, while the girls went even redder. “Let’s see how this is coming along,” their master said, pointing at the great black pot on the fire, which gave off a smell of cooking meat, herbs and wine so delicious that for a moment Lucius thought his eyes were about to fill with tears. 7 ban‧ dy bandy legs curve out at the knees.—bandy-legged adjective (Definition from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Advanced Learner's Dictionary. At http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/bandy_1 8 swineherd swine‧ herd [countable] old use someone who looks after pigs http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/swineherd 9 overseer noun: supervisor masculine, -sora feminine; capataz masculine or feminine http://www.merriamwebster.com/spanish/overseer 10 highness noun 1 height: altura feminine 2 Highness: Alteza feminine <Your Royal Highness : Su Alteza Real> http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/highness Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 18 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . “It’s coming along as it should,” the cook told him. “You are master in this house, but in this kitchen, as long as I’m still alive, I am in charge. And you are not going to see or touch it until I say it’s ready.” “You’re cruel, like most beauties.” “And you know all about that, don’t you?” She had been a young girl when he was only just beginning to walk and had taken care of him when he came to spend the summer months with his grandparents. When he was a boy she was already a young woman and smiled on remembering how she had bathed him when he was a child and not even so much of a child. Looking at her now he could still see, or imagined he could see, in spite of all the wrinkles, the face of a happy, mischievous girl, a bit of a flirt almost without realizing. She had had a husband, another slave, of course, long dead now, children. Perhaps even one of those girls helping her now was one of her own. “Go on now,” the old woman said in a gentle tone, “We have work to do. It will be ready in an hour or so.” He found Alexander on the terrace. The view was beautiful from there, fields and forest, the hills in the distance a green so deep it was almost blue. “Let’s go inside,” he said when his cousin had greeted him. “It’s chilly.” He ordered the servant to bring wine, olives and cheese, and they took their places before the fire. It was a spacious room, sparsely furnished, one wall painted with a scene of nymphs bathing in a stream, done in a style so naive that Lucius had always found it amusing. “Have you gone by the kitchen?” his cousin asked. “How did you know?” “I guessed.” “It smells divine.” “The divine Lavinia,” Alexander said, with a hint of a smile. “Yes,” Lucius replied while the steward17 served them their wine and began to set the table. “Imagine, in Rome it’s not unusual to attend a supper of fourteen courses18, not counting the desserts of course, each one more elaborate and amazing than the one before, and great cooks are more famous than poets. But I doubt if many of those dishes would be as tasty as what our Lavinia is preparing for us today.” “Perhaps you’re exaggerating a bit.” “Always so careful, eh, Alexander?” “It was you, not I, who frequented those suppers, remember?” “That’s true enough.” “Though perhaps you paid more attention to your friends’ wives than to what you were eating.” “No doubt,” Lucius admitted with a smile, though it was not a memory he was particularly fond of. As a young man he had been vain19 and cruel, though no more so than any of the others of his circle. It had all been a game, dizzying20 and meaningless. He could remember the faces of the women he loved. Some were now dead, others had turned into respectable matrons21, still others amused themselves with young actors or poets whom they promoted with their money and influence and glared 22 at the younger women they saw around them with ill-concealed hatred11. “I admit there have been good cooks,” he went on, “and there still are some, but…” 11 ill-concealed hatred odio mal disimulado Spanish translation by T. Navés Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 19 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . “But you know very well that all your hosts were interested in was showing off their fortunes and ensuring that people would talk about them…” “That’s so,” Lucius replied. It was three years since he had been back to Rome and he didn’t miss it. He had been fed up when he left, fed up with streets that stank23 of urine and bad sewers12, of the people he knew with their clothes, their jewels, their houses and their armies of slaves, their foolish smiles and the fear in their eyes, fear that someone was about to take all that away from them, their enemies, the Emperor, death itself. The only thing that had bothered him, when he retired to the country, was the possibility that Julia would miss her friends and life in the capital. They had not been married long and they had scarcely known one another before the wedding. She was a young widow, from a good family but with practically no money. His wife had just died after a long illness. He was tired, indifferent. “They’ll think I wanted to get you away from temptation,” he had said to her, half joking. “Or that it’s you who’s running away from his lovers,” she answered. And he had noticed then that she had sad eyes but a mischievous13 smile. Running away, he thought, gazing into the fire. If only one could. Then the steward announced they could take their places at the table. The meal began with a salad of small leeks and onion, with fresh mint leaves, thyme , parsley25 and soft cheese, crushed in the mortar and seasoned with black pepper and olive oil. Then came a dish of lentils with coriander26, vinegar and honey. And finally the great serving dish loaded with stewed boar. Lucius gazed at his plate for a moment, savouring the aroma. He had reached the age when good food brings back memories, one after another, and he wanted to linger over them for a moment before he began to eat. “You were right,” Alexander said after they had eaten in silence for a few moments. “In what way?” “I would say Lavinia has surpassed herself.” “I think so,” Lucius agreed. The meat had a strong flavour and even after being marinated for two days still had to be cooked for hours to avoid its coming out tough. He noticed the taste of cumin27, a touch of honey in the wine sauce. “What would your Greek friends think if they saw you eating like this?” he asked his cousin. “Don’t they claim a man ought to put away the pleasures of the flesh if he wishes to attain the more exquisite pleasures of the mind?” “Perhaps that was why I could never make a philosopher,” Alexander replied, and catching the edge of bitterness28 in his voice, Lucius regretted joking in that way. Poor Alexander. He had been a beautiful youth in his day, with a brilliant mind. He could have remained in Rome and led a life of luxury and amusement, but he had preferred Athens where he could study at the Academy. And there he had stayed, until Caesar had had his father killed, to get his villa so the story went, though he ended up, as usual, taking everything else as well. Alexander had been forced to return, poor and in disgrace. His friends of years before turned their backs on him, he was no longer 24 12 13 sewer alcantarilla feminine, cloaca feminine http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/sewer mischievous: travieso/a, pícaro/a http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/mischievous Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 20 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . beautiful, and he spent the little money he had left paying for his pleasure with young men who offered themselves in the most sordid quarters in the city. When Lucius decided to move to the country he had invited him to accompany them. Julia was fond of him and enjoyed his conversation, particularly his bittersweet stories of his love affairs. He came and stayed. He spent the days sleeping, reading and chatting with the two of them. He was grateful and made an effort to be amusing and talkative. Only occasionally, when he forgot himself, would he let the sadness show in his glance29. “Lavinia told me once that it is not a particularly complicated dish,” Lucius said while they ate, “and I believe her. Complication is not necessarily the point, is it? We Romans let ourselves be taken in by virtuosity and ostentation. We have lost all taste for simplicity.” “In this and in many other things.” “I suspect I know what you’re referring to.” “Do you?” “I do,” Lucius said, dipping bread in the sauce. “But isn’t it possible that this nostalgia for the Republic that we flaunt14 – a Republic that we have never known, by the way – is not just a pose that we imagine gives us a sense of our nobility, makes us interesting when we stand in front of the mirror?” “You’re more sceptical than usual today, cousin,” Alexander replied. “You know very well what I think about the subject.” “Oh yes. And it’s what I think as well. Or believed that I thought. But I suspect, in spite of myself, that in the end it may be true what they say, that the Empire cannot be governed by a Republic of free men.” “One might ask then what the point of it is.” “It serves, perhaps,” Lucius replied, “to make it possible for men like us to eat a plate of stewed boar like this and talk about things we know nothing about, which are the only things worth talking about. Isn’t that enough for you?” “No,” his cousin said, sipping30 his wine. “Didn’t your beloved Plato try to educate tyrants?” “And Seneca too, as I remember,” Alexander responded with a smile. “Can you name anyone who has succeeded in doing so?” “No. But that’s of no importance. A man who thinks must, from time to time, confront reality, in order to think it once again.” “Your teachers taught you well,” Lucius said while the steward refilled his cup. “That’s a beautiful phrase.” “I have no interest in making beautiful phrases.” “I know, Alexander, I know. What was it Protagoras said about the gods?” “As to the gods,” Alexander replied, switching to Greek, “I cannot know whether they exist or not, nor, as regards their form, what they are like. Many things prevent me from knowing this: the difficulty of the question, for instance, and the shortness of men’s lives.” “Yes, Lucius murmured, “which is a beautiful phrase as well. And if it were all no more than that? Beautiful phrases?” “I don’t know what you mean,” Alexander said, intrigued. He could not remember ever hearing his cousin talk like that. “No,” Lucius murmured and ate another piece of boar meat. He was almost finished, sated, and as tended to occur to him after experiencing any sort of sensual 14 flaunt, transitive verb alardear, hacer alarde de http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/flaunt Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 21 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . pleasure, if he did not go to sleep at once, he began to feel a curious unease, a touch of inexplicable bitterness. “Do you know why we love wine, Alexander?” “I know why I do.” “Because it is the only thing that can, if only for a moment, make time stop.” The two of them had left off eating, and, with a glance, the steward asked Lucius if he should take away the platter. “No, Paulus, leave it a moment, perhaps I’ll eat a bit more.” “I couldn’t eat another bite,” Alexander announced, patting31 his little thin man’s belly. “Tell me, Alexander…” Lucius began and then fell silent. The autumn afternoon was drawing to a close, the sky – what they could see of it – growing dark over the forest and the fields. Now there was the glow of the fire in the fireplace, the light from the oil lamps that the steward had discreetly lit. “What is it that we want, Alexander?” Lucius went on after a moment. “What is it we have tried to do?” “I don’t know,” the other man said after a long pause, “perhaps just to see things as they are.” Lucius picked up his glass and drank. In the silence they could hear the wind coming up. “Well said,” he pronounced finally. “Thank you.” Shortly after that the swineherd came in. He had a frightened32 look on his face and was glancing from side to side, trying to take everything in at once, because he had never been in a house that was anything more than a hut 15 and wanted to be able to tell about it afterwards. “I saw…” he mumbled. “Good,” Lucius interrupted. “I understand. You can go.” And then, when the slave, scuttling like a crab, had almost reached the door: “Wait.” Lucius, rising from his chair, picked up a piece of boar meat with two fingers. “No doubt you’ve never eaten this before, and you’ll never eat it again. Open your mouth.” The swineherd, after hesitating for an instant, obeyed, and Lucius popped33 the piece of meat into his mouth and smiled as he watched him chew34 on it with the two or three molars he had left. “Now go,” Lucius ordered. “I haven’t much time.” He turned to Alexander. “In ten, fifteen minutes at most,” he said, “an officer will walk in here with an order for my arrest. I want you to entertain him for a while. I’ll tell Paulus to bring out another platter of meat.” “No,” Alexander said, staring at him openmouthed35. “I’ve been a soldier. I know what they’re like,” Lucius went on, one hand on his cousin’s shoulder. “There are tasks one cannot entrust36 to a slave, however loyal he might be. Talk to him, give him some wine, a dish of the stewed boar, which, by the way, was superb, don’t you think?” “It was,” Alexander said in a whisper37, with his head lowered because he could not look him in the eye. 15 hut noun cabaña feminine, choza feminine, barraca feminine http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/hut Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 22 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . “Everything has been taken care of. You will have what you need to live well. Julia will have money. She’ll be able to marry again.” “I’ll be alone.” “We are all alone, Alexander.” The philosopher took a few moments to raise his head. When he did, his eyes were bright with tears. “Let me then, for once, kiss you on the mouth.” “What a fool you are, my friend.” The officer entered with his helmet under his arm. He had left his escort outside with their horses. Later it would be necessary to feed all of them, find them somewhere to sleep, try to avoid their raping some unwary slave girl. The officer was a Praetorian, no longer young, with tired eyes and a face the colour and texture of old leather. He glanced at the table out of the corner of his eye, then spoke. “I’m looking for Lucius Severus, by order of the Senate.” “You mean of Caesar,” Alexander corrected. “I say what they tell me I’m supposed to say,” the officer replied. “And you don’t think,” Alexander asked, filling a glass of wine and handing it to him. “I think less and less,” the officer answered, accepting the glass, “and, you know, the less I think, the better things go for me.” “I can see you are a man with good judgement,” Alexander said. “Do you like boar, I wonder?” “I wouldn’t say no.” “We were eating when suddenly my cousin found himself indisposed. Would you like to try a bit in the meantime? He’ll be back shortly.” “Doesn’t seem like a bad idea,” the officer said, taking a chair. The steward set a plate in front of him and began to serve. “Tell me,” Alexander went on, taking a sip of wine, “what’s the news from the capital?” The officer finished his second dish of stewed boar, took a long swallow of wine and burped16. “Excuse me,” he said. “So where is he?” “This way,” Alexander told him. His voice was steady, but when he got to his feet he could feel the trembling in his legs. The bathroom smelt of moisture17, the tiles were still wet, the knife on the floor, the water in bathtub the colour of wine. He had sliced his wrists and the jugular vein as well, and his head lay back. Alexander leaned over to look into his open eyes. He thought perhaps he might still be able to see something in them, but there was nothing but emptiness. He closed them with his fingertips, then covered his own eyes with his hand. “I’ll tell them we got here too late,” the Praetorian said. “As always. Thank you. I believe that was the best boar I’ve ever eaten.” © David C. Hall (2010) The Autumn of the Heroes, English version of El Otoño de los Héroes. Premio Pou de la Neu 2008. V.2. 16 17 burp [bɜːp] sustantivo 1. eructo (m) verbo intransitivo 2. eructar http://www.spanishdict.com/translate/burp moisture noun humedad feminine http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/moisture?show=0&t=1289379648 Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 23 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 1 EVALUACIÓN INICIAL O DIAGNÓSTICA Una comunicación auténtica en el aula requiere encontrar vías de implicación de los alumnos en el proceso de aprendizaje. Una vez conozcamos lo que ya saben y su actitud ante los objetivos propuestos (evaluación inicial), debe iniciarse un proceso constante de reflexión que facilite al alumno y al profesor información y conocimiento de lo que está aprendiendo y enseñando (evaluación formativa). Al final del camino buscaremos maneras de comprobar el grado de consecución de los objetivos, a fin de ver los cambios que se han producido en los conocimientos, actitudes y capacidades del alumno (evaluación sumativa) (Ribé & Vidal, 1995, p. 101) La evaluación inicial es la que se realiza antes de empezar el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje, con el propósito de verificar el nivel de preparación de los aprendices para enfrentarse a los objetivos que se espera que logren. Fines o propósitos de la evaluación diagnóstica o inicial • Establecer el nivel real del alumno antes de iniciar una etapa del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje dependiendo de su historia académica; • Identificar aprendizajes previos que marcan el punto de partida para el nuevo aprendizaje. • Detectar carencias, lagunas o errores que puedan dificultar el logro de los objetivos planteados. • Diseñar actividades remediales orientadas a la nivelación de los aprendizajes. • Detectar objetivos que ya han sido dominados, a fin de evitar su repetición. • Otorgar elementos que permitan plantear objetivamente ajustes o modificaciones en el programa. • Establecer metas razonables a fin de emitir juicios de valor sobre los logros escolares y con todo ello adecuar el tratamiento pedagógico a las características y peculiaridades de los alumnos. Características de la evaluación diagnóstica • No supone asignar una nota, ya que de lo contarrio perdería la función diagnóstica de la evaluación. • No tiene por qué ser una prueba, puede ser una actividad programada. • Puede ser individual o grupal, dependiendo de si quieres tener una visión global o particular de tus alumnos. • No es sólo información para el profesor. Adaptado de http://www.santillanadocentes.cl/docentes2/recursos%20pdf/Evaluaci%C3%B3n%20Inicial.pdf Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 24 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . References tnaves@ub.edu Appel, R. y Muysken, P. (1996). Bilingüismo y contacto de lenguas. Barcelona: Ariel. Baker, C. (1993). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. (3ª edición ampliada, 2001) [versión castellana de la 1ª ed.: Fundamentos de educación bilingüe y bilingüismo. Madrid: Cátedra, 1993]. Broselow, E. (1990-92). Adquisición de segundas lenguas. En F.J. Newmeyer (Ed.), Panorama de lingüística moderna de la Universidad de Cambridge, Vol III: El lenguaje: aspectos psicológicos y biológicos. Madrid: Visor. Cassany, D. (1993): Reparar la escritura, Graó, Barcelona Cassany, D. (2001) Construir la escritura, Editorial Paidós, Barcelona. Centro Virtual Cervantes. Diccionario de términos claves de ELE disponible en http://cvc.cervantes.es/ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/diccio_ele/default.htm Consejo de Europa (2001). Marco común europeo de referencia para las lenguas: aprendizaje, enseñanza y evaluación. (2002) http://cvc.cervantes.es/obref/marco. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte - Instituto Cervantes - Anaya, 2003. Cortés Moreno, M. (2000) Guía para el profesor de idiomas: didáctica del español y segundas lenguas, Octaedro, Barcelona. Domínguez González, P. (2008) Destrezas receptivas y destrezas productivas en la enseñanza del español como lengua extranjera. Monográfico N 6. Marco ELE. Revista de didáctica del español como lengua extranjera. Disponible en http://www.marcoele.com/num/6/pdominguez_destrezas.pdf Eurydice (2005): Las cifras clave de la educación en Europa 2005. (Bruselas, Unidad Europea de Eurydice) [en línea]. Disponible en: http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/ressources/eurydice/pdf/0_integral/052ES.pdf Fernández García, F. (2007), Los niveles de referencia para la enseñanza de la lengua española, Marco ELE, 5: pp. 1-18. Figueras, N. (2005) El Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para las lenguas: de la teoría a la práctica, Carabela, 57: pp. 5-23 García Mínguez, M. L. (2001). Nuevas tendencias en la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras en Europa: un profesorado en vías de adaptación, Revista española de educación comparada, 7, pp: 357-372 García Santa-Cecilia, A. (1995). El currículo de español como lengua extrajera. Madrid: Edelsa. González Lloret, M. (2003) Task-Based Language Materiasl: En Busca de Esmeraldas. Language Learning &Technology, 7,1 Disponible en: http://llt.msu.edu/vol7num1/gonzalez/default.html Halliwell, S. (1993) La enseñanza de la Lengua Extranjera en la Educación Primaria. Madrid: Alambra Longman. Instituto Cervantes. (2007). Plan curricular del Instituto Cervantes. Niveles de referencia para el español. Madrid: Edelsa. http://archivodigital.cervantes.es/fichas/quienes_somos/plan_curricular/plan_curricular.htm Larsen-Freeman, D. (1997) Grammar and Its Teaching: Challenging the Myt hs. CAL Digest. Disponible en http://www.cal.org/resources/digest/larsen01.html Larsen-Freeman, D. y Long, M. (1994) Introducción al estudio de la adquisición de segundas lenguas, Gredos, Madrid. Liceras, J.M. (1992). La adquisición de lenguas extranjeras. Madrid: Visor. Lightbown, P. M. y Spada, N.(2006) How languages are learned (revised version). Oxford University Press, Oxford. Littlewood, W. (1996). La enseñanza comunicativa de idiomas. Introducción al enfoque comunicativo. Madrid: Cambridge University Press. Muñoz, C. (2002) Aprender idiomas. Barcelona. Paidós. Muñoz, C. (2007) CLIL Some thoughts on its Psycholinguistic Principles. Revista española de lingüística aplicada, (Models and practice in CLIL) Vol. Extra 1, 2007, 17- 24. http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2575488 Muñoz, C., Pérez, C., Celaya, M. L., Navés, T., Torras, M. R., Tragant, E., et al. (2002). En torno a los efectos de la edad en el aprendizaje escolar de una lengua extranjera. Eduling. Revistafòrum sobre plurilingüisme i educació. Publicación electrónica semestral del ICE de la Universitat de Barcelona, 1, http://www.ub.es/ice/portaling/eduling/eng/n_1/munoz-art.htm Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 25 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . Muñoz, C. y Navés, T. (2007) “Windows on CLIL in Spain” In A., D. Maljers, D. Marsh & D. Wolff, (Ed.) Windows on CLIL European Centre for Modern Languages, págs. 160-165. Disponible en http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/handle/2445/9142 Navés, T. (2008) Los efectos de la edad de inicio en el aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extrangera Miradas y voces. Págs. 259-266. Navés, T. (2009). Effective Content and Language Integrated Programmes en Y. Ruiz de Zarobe, Y and R M Catalán Second Language Acquisition and CLIL. Clevedon, Multilingual Matters, pp. 22-40. Navés, T. (2010) AICLE a corto y largo plazo. ¿Qué debemos aprender de los programas de inmersión y de buenas prácticas? Revista Educadores Naves,T. y Muñoz, C. (1999). The implementation of CLIL in Spain. En Marsh, D. & Langé, G. (Eds.) Implementing Content and Language Integrated Learning. A research-driven TIE-CLIL Foundation Course Reader. (TIECLIL.) University of Jyvskylaù, 145-157 Navés, T. y Muñoz, C. (2000) Usar las lenguas para aprender y aprender a usar las lenguas. Disponible en http://www.ub.es/filoan/CLIL/padres.pdf Navés, T., Muñoz, C., & Pavesi, M. (2002). “CLIL for SLA”. In D. Marsh & G. Langé (Eds.), The CLIL Professional Development Course. Milan: Ministero della' Istruzione della' Università e della Ricerca. Direzione Regionale per la Lombardia, pàgs. 93-102. Disponible en http://www.scribd.com/doc/17677609/SLA-for-CLIL-by-Naves-Munoz-Pavesi-2002 Navés, T. & Victori, M. (2009) “CLIL in Catalonia: an Overview of Research Studies” in Y. Ruiz de Zarobe, Y & D. Lasagabaster, CLIL in Spain: Implementation, Results and Teacher Training, Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Navés, T., Torras, M. R., y Celaya, M. L. (2003). Long-term effects of an earlier start. An analysis of EFL written production. En Susan Foster-Cohen and Simona Pekarek Doehler (eds.): EUROSLA Yearbook 3. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Pp. 103-129. Navés, T. (2010). The promising benefits of integrating content and language for EFL writing and overall EFL proficiency. En Yolanda Ruiz de Zarobe, Juan Manuel Sierra & Francisco Gallardo del Puerto. Content and Foreign Language Integrated Learning. Contributions to Multilingualism in European Contexts. Peter Lang. Nation, P. (2007) The four strands Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 1 (1), 2-13. Nunan, D. (2002). El diseño de tareas para la clase comunicativa. Madrid: Cambridge Universiy Press. Pastor, S. (2000) Teoría lingüística actual y aprendizaje de segundas lenguas en Cuadernos Cervantes 26: 38 -44. Pujol, M.; Nussbaum, L. y Llobera, M. (1998): Adquisición de lenguas extranjeras: nuevas perspectivas en Europa. Madrid. Edelsa. Ribé, R. y Vidal, N. (1995) La enseñanza de la Lengua Extranjera en la Educación Secundaria. Madrid: Alambra Longman. Richards, J., y Lockhart, Ch. (1998) Estrategias de reflexión sobre la enseñanza de idiomas. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Siguán, M. (2001). Bilingüismo y lenguas en contacto. Madrid: Alianza. Vázquez, G. (1991): Análisis de errores y aprendizaje de español/ lengua extranjera. Frankfurt. Peter Lang. Vega, M.y Cuetos, F. (coors.) (1999): Psicolingüística del español. Madrid. Trotta. Vinagre Laranjeira, M. (2005). El cambio de código en la conversación bilingüe: la alternancia de lenguas. Madrid: Arco Libros. Williams, M. y Burden R. L. (1997). Psicología para profesores de idiomas. Enfoque del constructivismo social. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Madrid: Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press. Wray, D. y Lewis, M. (2000) Aprender a leer y escribir textos de información, Morata, Madrid. Zanón, J. (1988). «Psicolingüística y didáctica de las lenguas: una aproximación histórica y conceptual (I)». Cable, 2: pp. 47-52. Disponible en: http://www.marcoele.com/num/5/02e3c099650f54607/psicolinguistica.pdf Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 26 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . Glossary of Terms, Collocations, Fixed-Expressions bone tired (see also dead tired) bone-tired (also bone-weary) adjective extremely tired http://oxforddictionaries.com/view/entry/m_en_gb0091610#m_en_gb0091610 dead tired Definition: extremely tired; exhausted Explanation: Used when speaking about exhaustion at the end of a long hard day. Examples: We were dead tired when we got back from our trip to Las Vegas. - He went straight to bed because he was dead tired. http://esl.about.com/library/glossary/bldef_305.htm 3 awoke awake past tense awoke past participle awoken [intransitive and transitive] 1 formal to wake up, or to make someone wake up: It was midday when she awoke. We awoke to a day of brilliant sunshine. 2 literary if something awakes an emotion, or if an emotion awakes, you suddenly begin to feel that emotion: The gesture awoke an unexpected flood of tenderness towards her. awake something to phrasal verb to begin to realize the possible effects of a situation: Artists finally awoke to the aesthetic possibilities of photography. Definition from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Advanced Learner's Dictionary. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/awake_2 4 Sunken cheeks sunken adjective /ˈ sʌŋ.kən/ adj • having fallen to the bottom of the sea They're diving for sunken treasure. • at a lower level than the surrounding area It was a luxurious bathroom, with a sunken bath. • (of eyes or cheeks) seeming to have fallen further into the face, especially because of tiredness, illness or old age She looked old and thin with sunken cheeks and hollow eyes. (Definition of sunken adjective from the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary) http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/sunken cheek noun ( FACE ) /tʃiː k/ n [C] the soft part of your face which is below your eye and between your mouth and ear The tears ran down her cheeks. rosy cheeks He embraced her, kissing her on both cheeks. (Definition of cheek noun (FACE) from the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary) http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/cheek_1 5 bone tired (see also dead tired) bone-tired (also bone-weary) adjective extremely tired Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 27 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . http://oxforddictionaries.com/view/entry/m_en_gb0091610#m_en_gb0091610 dead tired Definition: extremely tired; exhausted Explanation: Used when speaking about exhaustion at the end of a long hard day. Examples: We were dead tired when we got back from our trip to Las Vegas. - He went straight to bed because he was dead tired. http://esl.about.com/library/glossary/bldef_305.htm 6 gaze gaze [intransitive always + adverb/preposition] to look at someone or something for a long time, giving it all your attention, often without realizing you are doing so [= stare] gaze into/at etc Nell was still gazing out of the window. Patrick sat gazing into space (=looking straight in front, not at any particular person or thing). http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/gaze_1 7 weeds 2 weed noun: mala hierba feminine http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/weeds?show=0&t=1289319147 8 sprung 1 spring verb sprang or sprung, sprung, springing Translation of SPRING intransitive verb 1leap : saltar 2: mover rápidamente <the lid sprang shut : la tapa se cerró de un golpe> <he sprang to his feet : se paró de un salto> 3 to spring up : brotar (dícese de las plantas), surgir 4to spring from : surgir de transitive verb 1release : soltar (de repente) <to spring the news on someone : sorprender a alguien con las noticias> <to spring a trap : hacer saltar una trampa> 2 activate : accionar (un mecanismo) 3to spring a leak : hacer agua 9 paw paw noun [C] the foot of certain animals, such as cats and dogs paw (ALSO paw at) verb [T] to touch something with a paw I could hear the dog pawing at the door http://dictionaries.cambridge.org/define.asp?key=paw*1+0&amp;dict=A 10 pigsty pig.sty plural pigsties [countable] 1 a building where pigs are kept [= pigpen American English] 2 informal a very dirty or untidy place [= pigpen American English] The house was a pigsty, as usual. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/pigsty 11 whistle whistle '(h)wis l → n. a clear, high-pitched sound made by forcing breath through a small hole between partly closed lips, or between one's teeth. • a similar sound, esp. one made by a bird, machine, or the wind. • an instrument used to produce such a sound, esp. for giving a signal. → v. 1. [intrans.] emit a clear, high-pitched sound by forcing breath through a small hole between one's lips or teeth: the audience cheered and whistled | [as n.] (whistling) I awoke to their cheerful whistling | [as adj.] (whistling) a whistling noise. • express surprise, admiration, or derision by making such a sound: Bob whistled. “You look beautiful!” he said. • [trans.] produce (a tune) in such a way. • (esp. of a bird or machine) produce a similar sound: the kettle began to whistle. • Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 28 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . [intrans.] produce such a sound by moving rapidly through the air or a narrow opening: the wind was whistling down the chimney. • blow an instrument that makes such a sound, esp. as a signal: the referee did not whistle for a foul. • [trans.] (whistle someone/something up) summon something or someone by making such a sound. 2. (whistle for) wish for or expect (something) in vain: you can go home and whistle for your wages. blow the whistle on (informal) bring an illicit activity to an end by informing on the person responsible. ( as ) clean as a whistle extremely clean or clear. • (informal) free of incriminating evidence: the cops raided the warehouse but the place was clean as a whistle. whistle something down the wind let something go; abandon something. • turn a trained hawk loose by casting it off with the wind. whistle in the dark pretend to be unafraid. whistle in the wind try unsuccessfully to influence something that cannot be changed. - ORIGIN Old English (h)wistlian (verb), (h)wistle (noun), of Germanic origin; imitative and related to Swedish vissla ‘to whistle.’ The New Oxford American Dictionary, second edition. Ed. Erin McKean. Oxford University Press, 2005. Oxford Reference Online. http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t183.e86854 12 bow intransitive verb 1: hacer una reverencia, inclinarse 2 submit : ceder, resignarse, someterse transitive verb 1 lower : inclinar, bajar 2 bend : doblar http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/bow 13 threshold thresh‧ old [countable] 1 the entrance to a room or building, or the area of floor or ground at the entrance: She opened the door and stepped across the threshold. 2 the level at which something starts to happen or have an effect: Eighty percent of the vote was the threshold for approval of the plan. a high/low pain/boredom etc threshold (=the ability or inability to suffer a lot of pain or boredom before you react to it) 3 at the beginning of a new and important event or development be on the threshold of something The creature is on the threshold of extinction. Definition from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Advanced Learner's Dictionary. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/threshold 14 spiteful spiteful /'spaɪtfəl/ adjetivo ‹remark› malicioso; ‹person› malo; (resentful) rencoroso; it was ~ of you to blame her fue una maldad echarle la culpa a ella Diccionario Espasa Concise © 2000 Espasa Calpe: http://www.wordreference.com/es/translation.asp?tranword=spiteful spiteful ['spaɪtfʊl] adjetivo 1 (una persona) malo,-a, rencoroso,-a 2 (un comentario) malicioso,-a: that was very spiteful of you, fue muy perverso por tu parte Concise Oxford Spanish Dictionary © 2005 Oxford University Press: 15 blushed blush intransitive verb Translation of BLUSH : ruborizarse, sonrojarse, hacerse colorado http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/blush 16 wrinkle wrin‧ kle [countable] 1 wrinkles are lines on your face and skin that you get when you are old: Her face was a mass of wrinkles. Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 29 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . 2 a small untidy fold in a piece of clothing or paper [= crease]: She walked over to the bed and smoothed out the wrinkles. 3 iron out the wrinkles to solve the small problems in something —wrinkly adjective: her thin, wrinkly face Definition from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Advanced Learner's Dictionary. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/wrinkle_1 17 steward noun 1 manager : administrador masculine 2: auxiliar masculine de vuelo (en un avión), camarero masculine (en un barco) http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/steward 18 course noun 1progress : curso masculine, transcurso masculine <to run its course : seguir su curso> 2direction : rumbo masculine (de un avión), derrota feminine, derrotero masculine (de un barco) 3path, way : camino masculine, vía feminine <course of action : línea de conducta> 4: plato masculine (de una cena) <the main course : el plato principal> 5: curso masculine (académico) 6of course : desde luego, por supuesto <yes, of course! : ¡claro que sí!> http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/course 19 vain adjective 1 worthless : vano 2 futile : vano, inútil <in vain : en vano> 3 conceited : vanidoso, presumido http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/vain 20 dizzy dizzy 'diz → adj. (-zier, -ziest) having or involving a sensation of spinning around and losing one's balance: Jonathan had begun to suffer dizzy spells | (figurative) he looked around, dizzy with happiness. • causing such a sensation: a sheer, dizzy drop | (figurative) a dizzy range of hues. • (informal) (of a woman) silly but attractive: he only married me because he wanted a dizzy blonde. → v. (-zies, -zied) [trans.] [usu. as adj.] (dizzying) make (someone) feel unsteady, confused, or amazed: the dizzying rate of change her nearness dizzied him. - DERIVATIVES dizzily 'diz l adv. dizziness n. - ORIGIN Old English dysig ‘foolish’; related to Low German dusig, dösig ‘giddy’ and Old High German tusic ‘foolish, weak.’ The New Oxford American Dictionary, second edition. Ed. Erin McKean. Oxford University Press, 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press.http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t183.e22018 21 matron matron /máytr n/ n. 1. a married woman, esp. a dignified and sober one. 2. a woman managing the domestic arrangements of a school, prison, etc. - DERIVATIVES matronhood n. The Oxford American Dictionary of Current English. Oxford University Press, 1999. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t21.e18905 22 glare glare2 Hide phonetics verb [I] to look at someone in an angry way She glared at him and stormed out of the room. http://dictionaries.cambridge.org/define.asp?dict=CLD2&key=HW*15807&ph=on 23 stink Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 30 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . stink past tense stank past participle stunk [intransitive] 1 to have a strong and very unpleasant smell: It stinks in here! stink of His breath stank of alcohol. The toilets stank to high heaven (=stank very much). 2 spoken used to say that something is bad, unfair, dishonest etc: Don't eat there - the food stinks! The whole justice system stinks. stink something ↔ out phrasal verb to fill a place with a very unpleasant smell: Those onions are stinking the whole house out. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/stink_1 24 thyme noun tomillo masculine http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/thyme 25 parsley noun perejil masculino http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/parsley 26 coriander co‧ ri‧ an‧ der [uncountable] British English a herb, used especially in Asian and Mexican cooking [= cilantro American English http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/coriander 27 cumin noun comino masculine http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/cumin 28 bitterness noun amargura femenine http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/bitterness 29 glance glance [countable] 1 a quick look: He gave her a quick glance and smiled. sidelong/sideways glance She couldn't resist a sidelong glance (=a look that is not direct) at him. take/shoot/throw/cast a glance (at somebody) (=look at someone or something quickly) The couple at the next table cast quick glances in our direction. The brothers exchanged glances (=looked at each other quickly). 2 at a glance a) if you know something at a glance, you know it as soon as you see it: He saw at a glance what had happened. b) in a short form that is easy to read and understand: Here are our top ten ski resorts at a glance. 3 at first glance/sight when you first look at something: At first glance, the place seemed deserted. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/glance_2 30 sip sip verb /sɪp/ v [I or T] (-pp-) to drink, taking only a very small amount at a time This tea is very hot, so sip it carefully. Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 31 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . She slowly sipped (at) her wine. sip noun n [C] http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/sip 31 pat pat past tense and past participle patted, present participle patting [transitive] 1 to lightly touch someone or something several times with your hand flat, especially to give comfort [↪ stroke]: He patted the dog affectionately. 2 pat somebody/yourself on the back to praise someone or yourself for doing something well: You can pat yourselves on the back for a job well done http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/pat_1 32 frightened adjective asustado temeroso http://www.merriam-webster.com/spanish/frightened pop verb ( PUT ) 33 /pɒp/ /pɑːp/ v (-pp-) [T + adverb or preposition] informal to put or take something quickly If you pop the pizza in the oven now, it'll be ready in 15 minutes. He popped his head into the room/round the door and said "Lunchtime!" Pop your shoes on and let's go. pop pills informal to take pills regularly, especially ones containing an illegal drug A decade of heavy drinking and popping pills ruined her health. http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/pop_10 34 chew chew 1 [intransitive and transitive] to bite food several times before swallowing it: This meat's so tough I can hardly chew it! chew at/on a dog chewing on a bone 2 [intransitive and transitive] to bite something continuously in order to taste it or because you are nervous chew on We gave the dog an old shoe to chew on. chew your lip/nails chew gum/tobacco 3 chew the cud if a cow or sheep chews the cud, it keeps biting on food it has brought up from its stomach 4 chew the fat informal to have a long friendly conversation ➔bite off more than you can chew at BITE1 (10) chew on something phrasal verb informal to think carefully about something for a period of time chew somebody ↔ out phrasal verb to talk angrily to someone in order to show them that you disapprove of what they have done: John couldn't get the guy to cooperate and so I had to call and chew him out. chew something ↔ over phrasal verb to think carefully about something for a period of time: Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 32 - Hall & Naves (2011) Life in the time of the Roman Empire: Exploiting a short story in TBLT-CLIL . Let me chew it over for a few days. chew something ↔ up phrasal verb 1 to damage or destroy something by tearing it into small pieces: Be careful if you use that video recorder. It tends to chew tapes up. 2 to bite something many times with your teeth so that you can make it smaller or softer and swallow it: The dog's chewed up my slippers again. Definition from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Advanced Learner's Dictionary. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/chew_1 35 openmouthed boquiabierto http://diccionario.reverso.net/ingles-espanol/open-mouthed 36 entrust en‧ trust [transitive] to make someone responsible for doing something important, or for taking care of someone entrust something/somebody to somebody She entrusted her son's education to a private tutor. be entrusted with something/somebody I was entrusted with the task of looking after the money. Definition from the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Advanced Learner's Dictionary. http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/entrust 37 whisper whisper → v. speak very softly using one's breath rather than one's throat. • (literary) rustle or murmur softly. • (be whispered) be rumoured. → n. 1. a whispered word or phrase, or a whispering tone of voice. • (literary) a soft rustling or murmuring sound. • a rumour or piece of gossip. 2. a slight trace; a hint: a whisper of interest. - DERIVATIVES whisperer n. whispery adj. - ORIGIN OE hwisprian, of Gmc origin, from the imitative base of whistle. The Concise Oxford English Dictionary, Twelfth edition . Ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press, 2008. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t23.e64666 Teresa Naves tnaves@ub.edu 106753404 http://sites.google.com/site/navesteresa/apac - 33 -