Financial Statements Explained

advertisement

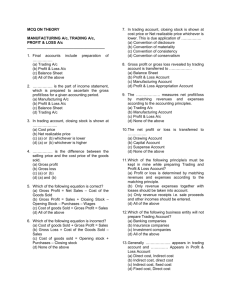

Financial Matters Explained Accrual Accounting Accrual accounting measures the periodic performance and position of a business in terms of the "economic events" that occur in the period, regardless of when their related cash transactions occur. For example if, in March, you were to purchase a wad of trading stock through a cooperative which did not issue a single, consolidated invoice until the first week in April, which you then settled by a payment in May, your cash-based accounting would show the in-flow of cash from sales of that stock in March, but no outflow for its purchase until May. In this simple example, March's profits would be falsely inflated, and May's falsely deflated. It's not a lot different to the problem you would suffer if the fuel gauge on your car had a twomonth lag in its reading: it would be useless - and, in many respects, an accounting system with that order of lag is also pretty useless as a tool for measuring real-time performance in a real live business! The problem I have outlined above is a real one for those who attempt to run a fast-growing business via cash accounting, and it's further exaggerated when they attempt to do so solely via their Profit & Loss Statement, so this might be a good time to revise "Accounting 101" and some of the basic facts about "the books". Trading Account This is often presented as "the top consists of all Sales Income for a making those sales (Cost of Sales), for the period. bit" of a Profit & Loss Account and period, less the costs associated with and its bottom line is your Gross Profit Cost of Sales, by the way, obviously includes the purchase price of the stock sold but, less obviously for many people, also includes any other costs associated with getting that stock to the point of sale (transport, insurance, duties, other services), and all labour costs associated with its preparation, transformation or delivery. These might include technicians' or process workers' wages as well as superannuation, work cover insurance, long service leave accruals (there's that word again!) or, in a service industry, the salary and associated costs of the service provider. Key Concept: Gross Profit is all that you have to meet the other expenses associated with running your business. It must be measured regularly and protected. Profit & Loss (P&L) The Profit and Loss Statement (or "Account") starts where the Trading Account ends - with the Gross Trading Profit - and proceeds to list all of the other expenses (sometimes called "fixed costs" or "overheads" because they tend to be relatively static regardless of the volume of sales). 1 Gross Profit minus Expenses gives us our Net Trading Profit and, for most businesses, it is this figure on which the company pays taxes. A common distortion of Net Profit arises from owners not accounting for their input to the business by drawing a regular and realistic salary - one that bears some resemblance to what they would have to pay a person with their skills, knowledge and dedication, to run the business at least as effectively as they do. We also see a few examples of owners who own their own premises but draw a low or no rent, thus subsidising their business with the use of their assets, and distorting their profits. Non-Trading Financial Transactions If a business generates some purely financial transactions that are, strictly speaking, not part of its normal business trading activities (for example, interest earned on cash deposits, or interest incurred on loans) these are traditionally brought to account after the trading profit, and before tax liabilities are calculated. This practice enables the business operator to gain a clear picture of the profits they are generating purely as a result of their trading, before they account for financial income or expenses. Balance Sheet The Balance Sheet is our record of what the company owns balanced against what it owes, and will always display an equal figure on both sides for the simple reason that anything "left over", whether a debt or an asset, is owed to the business by the owners, or is owed by the business to the owners. This difference is termed Capital and, in a healthy company, will usually be owed to the owners (shareholders). The major items of interest when using a Balance Sheet to provide part of the picture in relation to the trading performance of the business, are: the balance of any loan (including overdraft) accounts to and from the business, and the total value of Trade Debtors (this is an asset "something owned by or owed to the business") and Trade Creditors (a liability - "something owed by the business"). A common rule of thumb for Debtors and Creditors is to attempt to balance them (make sure that we are using as much of other people's money as other people are using of ours) - then add a "fudge factor" of around 10% on the Debtors' side, because we know we will always pay 100% of our Creditors' bills for the goods and services they provide, while we don't enjoy the same certainty that we will collect 100% from our Debtors for the goods and services that we have provided to them. The relevance of the Balance Sheet when it comes to judging our trading performance, centers mainly around shifts in the balance of what is owed to us and what we owe to others (except for the Shareholders). Regardless of our Net Profit, any shift that lessens our Assets relative to our Liabilities represents a lessening in the ultimate value of our business. 2 Using Your Accounts as a Dashboard Let's have a quick look at how we might interpret a set of accounts to determine how we have traded over the last month. In a cash model, if we were busy and now have more money in the bank than at the end of last month, the tendency is to think that we have had a good month. But, what won't be obvious without reference to our Balance Sheet items, is that we may have bought a large amount of stock on credit (we won't have to pay for that for a month or more) and sold all of it at such thin margins that they did not even cover our expenses. Sure, we feel great with a pile of money in the bank right now, but wait until the hangover hits next month when we have to pay our Suppliers! Working from our Trading Account, P&L and Balance Sheet, however, we would have gained a different picture of our performance, become aware of the low margins more quickly, and have been in a better position to correct pricing (or purchasing) to turn the matter around. Our Trading Account would tell us instantly that despite heavy sales activity, our Gross Profit was low (the direct result of low margin sales). Next, our P&L would tell us that our Expenses are now closer to the value of our GP than last month (i.e: our Net Profit is dropping). And finally, our Balance Sheet will show us the size of the debt that we have to address, and how much we have in the bank to do that. 3