chapter 46: arthropods

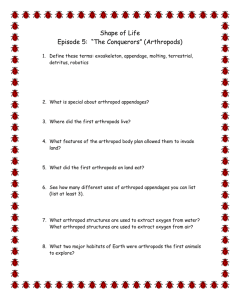

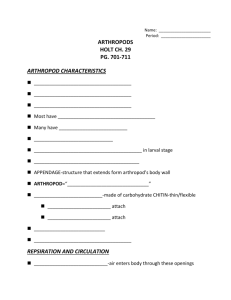

advertisement

CHAPTER 34: COELOMATE INVERTEBRATES WHERE DOES IT ALL FIT IN? Chapter 34 provides more detail about the diversity of animals highlighted in Chapter 32. It goes into more detail about modern animals. Students should be encouraged to recall the principles of animal classification covered in Chapter 32. Segmentation should be reviewed. The information in chapter 34 does not stand alone. Students should know that coelomates are interrelated and originated from a common ancestor of all animals. SYNOPSIS Still another way of organizing the animal kingdom is to group all coelomate, invertebrate animal phyla together based on the presence of true body cavities and no backbone. This would include the phyla that contain mollusks, annelids, arthropods, and echinoderms. Phylum Mollusca consist of the mollusks that include a wide variety of animals: snails, slugs, clams, scallops, cuttlefish, octopuses, squids, and many others. All mollusks are bilaterally symmetrical, have a visceral mass, and a muscular foot. Digestive, reproductive, and excretory organs are located within the visceral mass. Respiratory organs, gills or lungs, are located within the mantle cavity. Many of them possess durable external shells, a product of the outer layer of the mantle; others have internal shells and a few possess no shell at all. Most mollusks exhibit a trochophore larval stage that may be followed by a second veliger larval stage. They are divided into seven classes, the ancestral form most closely resembling the chitons, class Polyplacophora. The class Gastropoda consists of over 40,000 species of snails, slugs and similar animals that have a distinct head with tentacles and glide on a mucus layer that is secreted by the foot. Their visceral mass may be enclosed in a single spiral shell and is asymmetrical because of torsion during development. Class Bivalvia are made up of about 10,000 species of bivalves. Bivalve mollusks possess two shells hinged together at the dorsal edge. They lack distinct heads or radulas and are generally filter feeders. Octopuses, squids, and nautiluses comprise the class Cephalopoda. They have distinct heads and a series of tentacles evolved from the muscular foot. Cephalopods have highly developed nervous systems with elaborate eyes. They are the most intelligent and the largest invertebrate. Segmentation was another evolutionary key transition feature. Phylum Annelida or the Annelids are most likely the first segmented worms. Segmentation allows for more efficient locomotion as it increases overall flexibility. If an organ in one segment is damaged, duplicate organs in other segments continue to operate. Each segment is an individual hydrostatic unit, capable of independent contraction that possesses external chitinous bristles called setae. Annelids are constructed as a tube (the digestive tract) within a tube (the coelom). They have an organized nervous system with a well-developed brain and separate ganglia in each segment. Annelids possess a closed circulatory system with pulsating “hearts,” but lack discrete respiratory organs. Gas exchange occurs across the surface of their skin, limiting their size and restricting them to moist environments. They are divided into three classes: class Polychaeta (clamworms, plume worms, scaleworms, lugworms, twin-fan worms, sea mice, peacock worms and other marine worms), class Oligochaeta (earthworms), and class Hirudinea (leeches). Polychaetes or marine worms are active predators and clearly ancestral to the other classes and related to mollusks by their trochophore larvae. They move about by fleshy, paddlelike flaps called parapodia. Class Oligochaeta or the earthworms are 258 represented by both terrestrial and aquatic forms, although the most common form is readily found in nearly everyone’s backyard soil. Class Hirudinea consist of the highly specialized leeches, frequently parasitic worms and that clearly evolved from the Oligochaetes. Leeches have been used in medicine for centuries and are still used following surgery to help remove excess blood from tissues. Three phyla of animals share characteristics with and are intermediate between the protostomes and the deuterostomes. They include the phylas of Phoronida, Ectoprocta, and Brachiopoda. Collectively they are called the lophophorate animals. They all exhibit a circular or U-shaped ridge around the mouth that functions in gas exchange and food collection. Their coelomic cavity lies within the lophophore. They vary most greatly in their developmental processes, either being protostome-like or deuterostome-like, but all possess clearly protostomic ribosomes. Phylum Phoronida consist of about 10 species. Phoronids secrete a chitinous tube and live its life within it, extend tentacles to feed, have a U-shaped gut, and lie buried in the sand or attached to rocks. Phylum Ectoprocta consist of some 4000 species of bryozoans. They live in patches of moss on the surfaces of rocks and seaweeds and secrete a chitinous chamber called a zoecium. Phylum Brachiopoda consists of about 300 species of brachiopods. Many species resemble clams with two calcified shells. Two more innovations arose after the annelids—the development of jointed appendages and an exoskeleton. With the advent of rigid exoskeletons, jointed appendages were necessary to allow efficient movement in a terrestrial environment. These appendages are modified into various types of antennae, mouthparts, and legs. All arthropods have jointed appendages that may be modified into specialized structures, such as antennae, mouthparts, or legs. Although they lack overall intelligence, arthropods are ecologically a highly successful group, with over 1,000,000 known species that comprise about two-thirds of all the named species on earth. They can be found in all habitats on earth and may be a result of their generally small size. All arthropods have a rigid external skeleton or exoskeleton made of chitin and protein, which protects the animal from predation and prevents water loss. The exoskeleton is both tough and flexible, but must be shed periodically, a periodic ecdysis in order to grow larger. It is unlikely that extremely large arthropods could survive because of the large mass of exoskeleton and the necessity to molt the exoskeleton for growth. Additionally, all arthropod bodies are segmented. Some individuals have a large number of separate segments, while others have segments that are fused into functional groups through the process of tagmatization. The compound eye is another important structure in many arthropods as it is made up of many visual units called ommatidia as opposed to the single lens, simple eye. They are internally characterized by a reduction of the coelom to mere cavities surrounding the reproductive organs and some glands. They possess an open circulatory system with a longitudinal heart and no closed blood vessels. Although arthropods possess well developed nervous system with an anterior brain, the majority of body activities are actually controlled by ventral ganglia. Because of this, many insects continue activities for a period of time even when decapitated. In addition, the brain acts through inhibition rather than stimulation as in the vertebrates. The closed respiratory system of the terrestrial arthropods is made up of a series of hollow, branching tubes called tracheae. Some arthropods have book gills or book lungs alone or in addition to tracheae, while others possess typical aquatic gills. Several forms of excretory systems exist among the arthropods; the primary component of terrestrial arthropods is the 259 Malpighian tubules. The phylum Arthropoda is traditionally divided according to the structure of appendages. The 35,000 species of crustaceans is a group of primarily aquatic organisms including crabs, shrimps lobsters, crayfish, barnacles, water fleas, pillbugs, and others. Most possess two pairs of antennae, three types of chewing appendages, and various numbers of pairs of legs. The appendages of the crustaceans are biramous or two-branched. Decapod crustaceans include shrimp, lobsters, and crabs. Terrestrial and freshwater crustaceans include about 4500 species with the most familiar being the pillbugs, sowbugs, sand fleas, and the copepods. Sessile crustaceans include barnacles. Arachnida consist of over 57,000 species of spiders, mites, ticks, and scorpions. All possess chelicerates, fangs, or pincers that evolved from the most anterior pair of appendages. The next pair of appendages, pedipalps, resembles legs but is not used for locomotion, but instead is used as specialized copulatory organs. The order Araneae consists of about 35,000 species of spiders. The order Acarni consists of about 30,000 species of mites and ticks. Class Merostomata includes the horseshoe crabs. It is likely that the horseshoe crabs evolved from the now extinct trilobites. The class Pycnogonida includes the sea spiders. The group Chilopoda (centipedes) and group Diplopoda (millipedes) have bodies that consist of a head region followed by many segments bearing paired appendages. There are 2500 known species of centipedes; all are carnivorous mostly feeding on insects, with the first pair of appendages modified into a pair of poison fangs. Their bites can be toxic to humans, painful and dangerous. There are over 10,000 species of millipedes and probably six times this number exists. They are herbivores, feeding on decaying vegetation and can excrete a bad-smelling fluid that is protection against attacks. Insecta is the largest group of organisms on the earth consisting of approximately 90,000 described species. They characteristically have three body segments with three pairs of legs attached to the thorax. Some insects possess wings, although these structures are not derived from appendages as are the wings of vertebrates. They possess a wide variety of sense receptors that are involved with reproductive activities as well as food collection. Insects undergo hormonally controlled metamorphosis or molting from juvenile to adult stages. Some insects, like grasshoppers, exhibit simple metamorphosis. Others like bees, house flies, and butterflies undergo complete metamorphosis. This large group includes the: order Coleoptera (beetles); order Diptera (flies); order Lepidoptera (butterflies, moths); order Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, ants), order Hemiptera (true bugs, bedbugs); order Homoptera (leafhoppers, aphids, cicadas; order Orthoptera (grasshoppers, crickets, roaches); order Odonata (dragonflies); order Isoptera (termites); and order Siphonaptera (fleas). More advanced animals exhibit two different kinds of embryological patterns. Protostomes, including mollusks, annelids, and arthropods, exhibit the same pattern seen in noncoelomates; the mouth develops from the blastopore. In deuterostomes, echinoderms, chordates, and a few small phyla, the blastopore becomes the anus. Protostomes also exhibit spiral cleavage, deuterostomes radial cleavage. The developmental fate of a protostome cell is fixed when that cell first appears; a deuterostome cell’s fate is not fixed until later in development. Finally, protostomes have a simple 260 and direct development of the coelom from mesoderm tissue. Deuterostome coelomic development is more complex as groups of cells move around during development forming new tissue associations. This is also the first time that endoskeleton makes its initial appearance. The 6000 species belonging to the phylum Echinodermata is unusual in that its larvae exhibit bilateral symmetry, while the adults are radially symmetrical. The secondary radial symmetry may be associated with the mobility of the phylum. Bilateral symmetry is very important for mobile organisms, in echinoderms the larval form. The adults are relatively sessile, appropriate for radial organisms. They possess an endoskeleton composed of calcium-plate ossicles covered by a thin epidermis. They have no head or brain and their bodies follow a five-part plan. Echinoderms have a unique water vascular system that controls the extension and contraction of flexible tube feet used in locomotion and/or feeding. The coelom connects with a complicated system of tubes and helps provide circulation and respiration. Respiration and waste removal occurs across the skin through projections called skin gills. They are capable of extensive regeneration in addition to normal sexual reproduction. Echinoderms are divided into six visually different classes. The class Crinoidea includes the sea lilies and feather stars, multi-armed filter feeders whose mouth and anus are located on the upper surface. Class Asteroidea includes the sea stars, active marine predators. Class Ophiuroidea consist of the brittle stars that appear similar to sea stars, but their arms are set off more sharply from the central disk. Sea urchins and sand dollars, lacking arms, are two of the 950 living species that are members of the class Echinoidea. These latter three classes have mouths located on the under surface (aboral surface). The class Holothuroidea least resembles the other echinoderms. Their body form is well described by their common name, sea cucumber. Their ossicles are microscopic plates embedded in a leathery skin and they lack spines. The most recently discovered class Concentricycloidea are commonly called sea daisies. These diskshaped animals have the typical five-part radial symmetry, but lack arms. Their tube feet are arranged along the edge of the disk, not along radial lines like the other classes of echinoderms. Both species are unusual with regard to their digestion. One has a saclike stomach without intestine or anus. The other completely lacks a digestive system, absorbing nutrients through a membrane on the mouth. LEARNING OUTCOMES Understand the basic organization of a mollusk and the importance of the mantle. Describe the differences in body plan, reproduction, feeding, and respiration among the gastropods, bivalves, and cephalopods. Explain the advantages of segmentation in coelomic organisms and give an example of each phyla. Understand the basic organization of annelids and how their organ systems compare to those of mollusks. Indicate how the annelids are more advanced than the mollusks. Understand how earthworms, polychaetes, and leeches differ from one another. Describe lophophorates and indicate their relationships to protostomes and deuterostomes. Understand the necessity for segmentation and jointed appendages in the arthropods. 261 Explain the structural and functional size limitations in the arthropods. Identify the major external features of arthropods that distinguish them from all previously presented animal phyla. Describe ecdysis as it applies to arthropods and understand why it is necessary. Understand the basic internal organization of the arthropods. Describe the diversity among the major groups: crustaceans, arachnids, centipedes/millipedes and insects. Describe the external and internal characteristics of the class Insecta. Describe the major differences between the orders of Insecta. Understand the complexities of insect metamorphosis and differentiate between simple and complete metamorphosis. Differentiate between protostomes and deuterostomes. Describe the general body plan of an adult echinoderm. Understand the importance of the echinoderm water vascular system. Describe regeneration in echinoderms and how it relates to reproduction. Differentiate among the six classes of echinoderms in terms of body plan, locomotion, tube feet modifications, reproduction, and feeding strategy. Contrast the classes of echinoderms. COMMON STUDENT MISCONCEPTIONS There is ample evidence in the educational literature that student misconceptions of information will inhibit the learning of concepts related to the misinformation. The following concepts covered in Chapter 34 are commonly the subject of student misconceptions. This information on “bioliteracy” was collected from faculty and the science education literature. Students do not understand the relationship between symmetry and lifestyle Students do not fully comprehend the location of the coelom in animals Students are unsure that many of the lower animals are classified as animals Students think that all animals evolved at about the same time Students believe that deuterostomes evolved from protostomes Students believe that all animals are mobile Students believe that most animals are vertebrates Students are unaware of the limitations of different types of respiratory systems Students are unaware of the limitations of different types of circulatory systems Students are unfamiliar with interrelations of the different organ systems Students do not know the full significance of segmentation Students believe that all animals have identical organ system structures Students believe that animals exclusively reproduce sexually Students are unaware of molecular methods of animal classification INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGY PRESENTATION ASSISTANCE 262 Suggest that your students create a flow chart of the animals according to symmetry, type of coelom, and whether protostome or deuterostome. Discuss the advantages of segmentation in terms of automobiles with multicylinder engines. If one piston is slightly off, the rest can power the car. If one of the chambers in the battery or radiator go bad, the rest continue to work. But, if the water pump fails so does the vehicle! Compare flat, round, and segmented worms in terms of advances in structure and function. Discuss the advantages of being hermaphroditic. Generally the animal needs only to find another animal like itself rather than finding one that is the opposite sex. If both reproductive systems are functional, twice as many offspring can be produced. Many of the names associated with arthropods involve “poda” or “pedia” indicating the importance of the characteristics of the appendages in determining classification. Discuss why it is unlikely that the giant insects of science fiction movies could evolve given present conditions on the earth. Consider why it is likely that arthropods could “inherit the earth” if the ozone layer is destroyed. Daddy longlegs produce a strong toxin. It does little harm though, because their jaws are too small to grasp animals larger than insects and other spiders. Compare the growth of the echinoderm endoskeleton to that of the arthropod exoskeleton. Discuss the advantages associated with the echinoderms not having to molt periodically. Discuss the lack of fresh water echinoderms in relation to the osmolarity of sea water versus fresh water. Sea stars and brittle stars are relatively easy to maintain in a salt water aquarium, they eat almost anything. Buy a “living rock community” even if you don’t have a permanent marine aquarium. Most supply companies sell them. They have myriads of marine plants and animals from protists to microscopic sea cucumbers. Using a dissecting microscope, watch a sea cucumber project its mucus-covered tentacles through the sand particles and sweep them through its mouth! HIGHER LEVEL ASSESSMENT Higher level assessment measures a student’s ability to use terms and concepts learned from the lecture and the textbook. A complete understanding of biology content provides students with the tools to synthesize new hypotheses and knowledge using the facts they have learned. The following table provides examples of assessing a student’s ability to apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information from Chapter 34. Application Have students describe the value of a coelom over the psuedocoelom condition. 263 Analysis Synthesis Evaluation Have students explain value of segmentation in the evolution of different types of mobility. Ask students to explain the benefits and negative impacts of segment specialization. Have students compare and contrast the segmentation specialization of annelids and arthropods. Have a student explain the benefits of an animal that has mobile larvae and immobile adult forms. Ask students to explain the evidence supporting that echinoderms evolved from segmented ancestors. Ask students to explain the outcomes of increasing the number of hox gene mutations in arthropods. Have students hypothesize about the environmental outcomes of overusing insecticides in agricultural areas. Ask the students to find a medical application that exploits the knowledge of shell secretion in mollusks. Ask students evaluate the effectiveness of a flea control treatment that prevents chitin synthesis. Ask students to evaluate the value of using cephalopods as a model of understanding the human brain. Ask students to evaluate the accuracy of using echinoderms as a way of understanding human embryological development. VISUAL RESOURCES Show photographs illustrating the diversity of mollusks and relate these multitudes to the variety of niches and habitats. These animals have developed a number of ways to solve the same problems, especially those of locomotion and feeding. Obtain small specimens of terrestrial oligochaetes, marine polychaetes, and/or pond leeches and view their movements on the overhead projector. (Not for too long or you will have cooked annelids. Perhaps they could be served over linguini with a garlic sauce and a side of escargot!) Conduct experiments with isopods by placing them in boxes, one moist and damp while the other side is exposed to sun and dry. Note how long it takes the ones to stop moving in the damp, dark side. 264 Show lots of slides to indicate the enormous diversity of these phyla. Living examples can be shown in silhouette using the overhead. This is a good way to show the differences between simple and complete metamorphosis. Be careful with winged varieties and certain specimens that cause immediate revulsion in humans. Your specimens may also become more active when warmed by the overhead. Dead specimens from a “bug” collection may work better. Have students go out and make their own insect collections—they will be surprised at all the different insects that can be collected from a small backyard. Identify the insects using a dichotomous key. Have students swap insects with other students. Show lots of slides to indicate the diversity of echinoderms. Most students in non-coastal regions know echinoderms only from the hard, dry specimens found in lab or as decorations. They are amazingly flexible, colorful organisms, readily seen in slides or films. Help students visualize the typical echinoderm form in the horizontally positioned sea cucumbers by projecting a slide or overhead improperly—with the tentacles and mouth facing downward. IN-CLASS CONCEPTUAL DEMONSTRATIONS A. Coelomates in Motion. Introduction This demonstration permits the class to see a live video-camera footage of the different organisms discussed in Chapter 33. Materials Computer with Media Player and Internet access LCD hooked up to computer Web browser linked to Racerocks.com at http://www.racerocks.com/racerock/eco/taxalab/taxonomy.htm Procedure & Inquiry 1. Explain to the class that you will be showing them videoclips of the animals covered in Chapter 34 2. Load up the website and click on the Animal drop-down icon. 3. Then use the cursor to select an organism and show the short videostream. 4. Have the students explain how the organism is characteristic of its phylum and class. 5. Ask the students briefly explain the types of information that can be gathered by watching the videocam recordings. USEFUL INTERNET RESOURCES 265 1. Images of coelomate animals are available from the University of California at Berkeley CalPhotos: Animal website. These images are valuable teaching resources for lecture and laboratory sessions. The site is available at http://calphotos.berkeley.edu/fauna/. 2. Memorizing the taxonomic information of unfamiliar animals is a tedious task for students. Research studies with relevance to human applications compel students to learn more about exotic organisms. A study called “Left-Right Asymmetry in the Sea Urchin Embryo Is Regulated by Nodal Signaling on the Right Side” published in Developmental Cell journal is a good discussion point for discussions on the evolution of “handedness” in bilateral organisms. Students can be asked to discuss the possible applications of this information. An abstract of article is located at http://biodev.obsvlfr.fr/publications/pdf/153.pdf. 3. The Tree of Life website provides up to date information about animal classification. It has useful information and images for showing students diversity of animals. The website can be found at http://tolweb.org/Animals/2374. 4. A bit of humor is a great way to break the tension of covering the complex taxonomy of animals. Students will be entertained knowing that the many of the world’s food problems can be solved by eating insects which are the most numerous of the coelomate invertebrates. Iowa State University hosts a website boasting edible meals made using insects and other coelomate invertebrates. The website can be found at http://www.ent.iastate.edu/misc/insectsasfood.html. Another insect recipe website is hosted by NatureNode at http://www.naturenode.com/recipes/recipes_insects.html. LABORATORY IDEAS A. Comparison of Segmentation This activity asks students to investigate the variation in segmentation between different coelomate invertebrates. a. Review the concept of segmentation to students. b. Tell students that they will be investigating the similarities and differences of segmentation in different coelomate invertebrates. c. However, tell them you want them to first see if there is any evidence of segmentation in the noncoelomates such as flatworms. d. Provide students with the following materials a. Planarian slide b. Preserved earthworm c. Preserved clamworm d. Preserved grasshopper e. Preserved chiton f. Microscope e. Instruct students to investigate and describe any evidence segmentation in flatworms f. Then tell the students to explain the similarities and differences in segmentation in the various coelomate invertebrates provided for examination. 266 LEARNING THROUGH SERVICE Service learning is a strategy of teaching, learning and reflective assessment that merges the academic curriculum with meaningful community service. As a teaching methodology, it falls under the category of experiential education. It is a way students can carry out volunteer projects in the community for public agencies, nonprofit agencies, civic groups, charitable organizations, and governmental organizations. It encourages critical thinking and reinforces many of the concepts learned in a course. 1. Have students do a lesson do a program “edible insects” for a civic group. 2. Have students tutor high school students animal diversity. 3. Have students volunteer on environmental restoration projects with a local conservation group. 4. Have students volunteer at the educational center of a zoo or marine park. 267