There are too many different theories on crime for one of them to be

advertisement

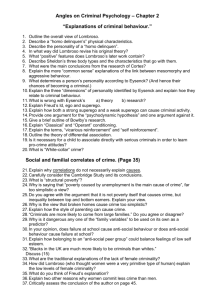

There are too many different theories on crime for one of them to be absolutely correct. Crime by definition is any act or failure to act that breaks the law of the land. Therefore with so vast a definition of crime, it is hardly surprising that there are a vast amount of differing theories attempting to explain the causes of crime. Each theorist normally has a specific stance, where they believe the causes of crime to begin. Theorists such as Lombroso use a physiological approach to explain the reasons for people committing crime, putting blame to actual physical features. Eysenck was a psychological theorist and looked at elements of the mind that could lead to criminal behaviour in later life. Durkheim and Matza identified that certain crimes usually occurred amongst similar social classes and investigated how issues in a person’s society and upbringing could lead them to commit crime. However each theory is not without its criticisms and it may be impossible to identify which has the best foundation to explain crime. Some of the first criminologists based their theories on biological investigations. Many believed that physical attributes contributed to a person’s behaviour. A view was common among many biological theorists that criminals were born, not made. Lombroso is one of the most famous biological criminalists and his theories are still widely discussed today. He saw criminals as a separate breed or species that possessed a variety of mental and physical characteristics which set them apart from “good” people. Examples of Lombroso’s theories of criminal attributes included; asymmetry in the face, sticking out ears like a monkey and an abundance of wrinkles as in apes. Lombroso’s approach was to assume that being a criminal was somehow to be explained through identifying these attributes in an individual. However, many people have criticised Lombroso’s theories. In his assessment of “criminal” physical attributes, Lombroso makes a repeated reference to apes and primitive features. Arguably, it does not provide an answer as to why delinquents commit crime. Lombroso created such a vast list of physical features that he found in a prison population that it is not possible that one person could have all these attributes. And even if there were such a man, that does not automatically mean that he will turn to crime. It could be argued that it was for people like Lombroso that criminals should assume an inevitability and self-affirming prophecy if they commit a crime. His views were published and the wider public could easily develop stereotype and persecute those who perhaps “looked like criminals” according to Lombroso’s definition. Since then, criminalists such as Durkheim have argued that this sort of social exclusion can be a catalyst to criminal behaviour. Women were seen by Lombroso to be less advanced in their primitive origins than men and consequently to be morally more deficient and have greater evil tendencies. He argued that “women criminals are monsters” because the female gender are a gentler breed so to stray away from this homely image into crime is a far greater evil than any man’s crimes. However, many argue that Lombroso’s analysis of female criminals is flawed. Many criminalists identified a link between upbringing, social status and crime. In fact upbringing was a determining factor in many psychological theories in regards to crime. As a result of this, sociological theorists began to emerge with ideas as to why crime took place. Emile Durkheim is renowned as one of the founding fathers of sociology and it was he who first made the connection between class, upbringing and crime. Durkheim pointed out that regulation becomes increasingly important as societies become more complex. Durkheim argued that people behaved the same if they were of the same social class and lifestyle. If people deviated from their social convention they were branded as outsiders. This could work in two scenarios: the first; that a member of an upstanding society of prosperity deviates, is excluded and therefore pushed into the clutches of crime, the second; that a member of a crimeridden society of poverty refuses to give in to peer pressure and is branded an outsider thus turning away from crime. However, Durkheim also identified that as economies and politics become more complex, society too evolves from the simple “servant and master” social divisions. Durkheim developed a new term describing a society during a pivotal turning point. According to Durkheim a state of anomie occurs when systems of moral regulation fail to keep up with the changes in the economic structure of society. Thus individual appetites, desires and ambitions are stimulated but insufficiently controlled or limited. As a result of this, crime exists. Smith and Natalier, two modern criminologists suggest that Durkheim’s theories are still very relevant today. They argue that Durkheim’s theories highlight the importance to think about the criminal justice system in the wider context of society, rather than as vast spheres largely independent of their social surroundings. It is impossible to create maxims that apply to all aspects of the criminal justice system for crime and punishment cannot be the product of pure reason. They would argue that according to Durkheim’s findings, only distinguishing right from wrong, legal from illegal can send messages of justice and morality to the wider public. Although these are glowing evaluations from Smith and Natalier, Durkheim’s theories were not without criticisms. Arguably, Durkheim’s work underplays the way in which systems of punishment are shaped by the nature and distribution of power in society. Durkheim, while acknowledging social change, holds fast to the stereotypes of certain social groups and assumes that everyone has the same moral values according to their class. He argues that all crime should be treated and punished the same, according to the collective conscience of the group in question. This is obviously a flawed assumption raises the question as to whether it is at all possible to have one single theory explaining the causes of crime. Many critics would argue that it is possible to identify criminal acts that simply don’t challenge moral outrage such as shoplifting. It is seen by the law as an offence but hardly offends the masses. Garland pointed out that there are circular elements to Durkheim’s theories to why laws are enacted and criminals punished. For example, Durkheim says that punishment should be determined by the wishes of the healthy conscience (ie those who abide by the norms of the collective). However, since crime is an act of rejecting convention, this is defying the collective conscience which makes it impossible to break societal stereotypes. Another renowned sociological theory came from David Matza. He worked alongside gangs in New York to investigate the reasons for youth crime and gang culture. He developed the notion of drift in which young people participate in criminal acts without fully intending to do so and without necessarily possessing values that condone crime. For example, a young person failing in school, subject to poverty and neglect would be far more likely to “drift” into the path of crime alongside other youths in a similar situation out of desperation for money, resources, excitement or even attention. Matza argued that delinquency did not emerge as a result of strongly deterministic forces such as hereditary genes, or biological features - these were theories he strongly rejected. Rather he thought crime was subject to a gentle weakening of the moral ties of society thus allowing room for some young people to drift into delinquency. However, Matza’s theories have had many criticisms from other sociologists. Travis Herschi believes that deviant behaviour is a result of conformity, or lack of, towards societal norms. He argues that no matter the upbringing, each person has a choice whether to abide by the conventions laid out by every society. Sociologist Jack Douglas also had criticisms of Matza’s theories and felt that no matter the cause of crime, a shift in blame cannot vanquish the deviant’s feeling of guilt when they realise that their actions are unacceptable to the rest of the law-abiding community. In conclusion, there are too many different theories on crime for one of them to be absolutely correct. The strongest claims each have their criticisms along with the weaker ones therefore it seems likely that in the matter of crime and justice, it is impossible to universalise a particular theory to apply to all matters. However, there are some theories that have more credibility than others. The most obvious criticism to biological theories is that they are horrendously outdated. With current developments in science, it is hard for a 21st Century population to believe that a man with sticking out ears and an “abundance in wrinkles” is more likely to commit crime than a man without. Also, the opinion of women being of equals to men is true for most of Britain so many of Lombroso’s arguments find themselves to be irrelevant and frankly absurd to today’s society. The psychological and sociological stances seem to be more relevant and current and it is possible that a combination of these two is the reason for crime today.