Electricity Sector in Kerala: A Comparative Perspective

advertisement

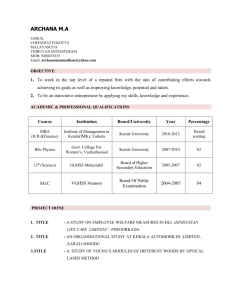

Electricity Sector in Kerala: A Comparative Perspective V. Santhakumar Centre for Development Studies, Prasanth Nagar, Trivandrum 695011, Kerala 1. Introduction and the Context This is a short essay on the current status of, and the challenges faced by, Kerala's electricity sector. However this essay does not address much the internal problems of the State Electricity Board like its losses, number of employees, and the level of inefficiencies etc, and these have been analysed by a number of studies in the past1. Instead the paper focuses on issues such as quality of electricity supply and reform efforts as viewed by the society. The evidence of the paper comes from a larger study on the social support/opposition to power sector reforms conducted in 14 states of India, which address the following question: Why do there is more opposition to electricity reforms in certain states than in others? Though the insights of this study based on a primary survey of about 7000 households in 14 states are not much relevant within the scope of this conference, it provides some insights as a 'by product', on the performance of Kerala's electricity sector vis-à-vis (1) the expectations of its consumers, and (2) the response of Kerala society towards electricity sector reforms. The study also provides a comparative picture of the performance of electricity sector in different states and this would give insights on where does Kerala stand in the company of other states. These insights are shared in this short article. As noted earlier, there have been a number of academic and consultant studies and commission reports during the last decade, on the performance of Kerala's electricity sector. A complete listing and reviewing of these studies is not attempted2. Most of these studies have identified the inefficiencies in the performance of KSEB, the extent and causes of its financial losses, and highlighted the need for some changes in the management of these organisations. There have been disagreements on the kind of institutional changes or reforms required, where in significant sections of the academic and political commentators have opposed attempts of radical restructuring including privatisation3. 1 These include numerous committees including Government of Kerala (1997, 1998a, 1998b) and Kannan and Pillai (2001) and Pillai and Kannan (2001). Rao et (1998) provide a comparative picture of performance of State Electricity Boards including that of Kerala. 2 Apart from those mentioned in foot note 1, other studies include Santhakumar (2003a, 2003b) and EISP (2000). 3 The left government in Kerala between 1996-2001, and the reform effort initiated during their time with the support of Canadian International Development Agency, went ahead with the assumption that a `profit centre' approach is to be followed for improving the effectiveness of KSEB. However neither that government nor its successor has not made any serious attempt to institute functioning profit centres. The current UDF government sought the assistance of Asian Development Bank, and their consultants suggested unbundling KSEB and making these unbundled units into state-owned companies, and to think about privatisation as a strategy to followed later on. The KSEB and the government did not accept these suggestions and hence could not avail the offered assistance from ADB. Some academics including Pillai and Kannan (2001) and several left-oriented political commentators have argued for keeping KSEB intact without unbundling or privatisation. They are arguing for `internal reforms' without changing the public sector and bundled monopoly characters of the Board. There are some broad limitations to these studies: (1) Current situation of KSEB is somewhat different from the one viewed by the studies conducted two to three years ago. Of late, there has been some improvement in the financial position of the SEB. Hence any discussion of the future challenges needs to be grounded on the current situation, which is different from that two to three years ago. (2) Most of these studies have looked at the inefficiencies of SEB and the need for reforms in isolation from the expectations of the society. For example, while a number of these studies have talked about the need for improving the quality of electricity supply, few have asked whether consumers are willing to bear the additional cost of improving the quality. This article addresses modestly some of these limitations. Moreover this study is based on primary data, and there are not many studies on electricity sector based on primary data4. This is important since the data on the actual tariff paid, and the quality of service encountered, by the consumers are not easily available in secondary information. The paper is organised in the following sections. The next section (2) provides some indicators that show a 'relatively comfortable' position of KSEB to meet the current demand. The factors that contributed to this situation have been discussed in section (3). The expectation of the people of Kerala vis-à-vis the performance of its electricity sector is also analysed in this section. This is followed by a discussion (in section 4) of the major challenges faced by the sector in near future, and the final section lists down certain issues that need to be addressed by the policy makers and the society. 2. `Relatively comfortable position of KSEB' We may consider the following as indicators of the relatively comfortable position of KSEB today. a. About 82% of the households in Kerala have access to electricity connection. In this regard, the state is one among a few major states, which could extent electricity connections to more than four-fifth of its households. b. There are no declared power interruptions today. However still there are undeclared and unexpected power interruptions. Our primary survey showed that only about 40 percent (as evident from Table 1) of the residential households have not experienced any form of power interruptions (based on a question whether they experience power cut during the last 24 hours). However when we compare this with the situation in other states, one can see that the state of affairs in Kerala in this regard is better than all other states except Tamilnadu. 4 Exceptions include the World Bank (2001) study on two states on electricity use in agriculture. Other primary data based studies include EISP (2000, 2002) and Santhakumar (2004). 2 Table 1: Duration of power failure/ power cut encountered by connected consumers during the last 24 hours (on the date of survey) Duration of power failure in minutes Kerala Orissa Tamil Nadu West Bengal Andhra Pradesh Uttar Pradesh Bihar Haryana Madhya Pradesh Rajasthan Karnataka No power cut 44.30 29.30 54.20 33.80 21.40 28.20 2.30 8.40 6.80 0.60 3.00 1-30 16.50 7.90 26.00 12.60 2.40 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 4.70 30-60 11.70 21.10 7.50 21.40 2.80 1.50 3.60 0.80 0.00 5.20 8.10 60-120 120-240 240+ 9.60 10.60 6.84 35.40 5.80 0.60 10.70 1.60 0.00 16.60 14.90 0.60 0.00 0.00 73.30 0.00 0.30 70.00 0.00 10.60 83.50 18.80 26.40 45.50 0.00 0.20 92.80 43.00 39.70 11.50 19.60 5.00 59.50 Average duration of power failure in minutes 73.15 94.34 21.82 58.44 281.18 645.31 1013.00 418.76 738.34 183.89 247.80 Source: Primary Survey conducted by the author in 2005. c. Even though quality of electricity supply is not very good, people are not willing to pay for better quality supply. (The state-wise willingness to pay more for higher quality based on the primary survey is given in Table 2). This willingness is lowest in Kerala (among the surveyed states), and it may be noted that willingness is higher among the states with relatively poor quality. Hence the current level of supply in Kerala seems to be in tune with (if not excess of) the economic demand (from the households) within the state. Thus enhancing investments to improve the quality may not generate adequate revenues from domestic consumers. This does not mean that KSEB should not invest in reducing losses or in computerisation, etc., where the returns would be much higher. Table 2: State-wide opposition to privatisation and willingness to pay more for better quality (Percentage of households) States Kerala Tamil Nadu (TN) Andhra Pradesh (AP) Orissa West Bengal (WB) Uttar Pradesh (UP) Madhya Pradesh (MP) Bihar Haryana Rajasthan Gujarat Karnataka All States No to privatisation 51.9 44.4 71.2 52.6 30.9 18.1 11.3 29.8 2.6 17.7 28.3 33.9 WTP 8.7 12.5 15.5 20.3 26.6 38.5 75.7 81.5 43.3 33.7 62.1 74.9 40.4 Source: Same as Table 1 3 d. Majority of the domestic consumers get electricity at highly subsidised rates. This is indicated by the distribution of the average cost of supply and the average tariff paid by the sample households in descending order (of the average tariff) in each state, given in Figure 1. As evident from Table A (in appendix) about 77% of the domestic consumers get electricity at an average rate of less than 2 Rupees. In this regard, the level of subsidy is one of the highest in Kerala. Thus residential consumers in Kerala get electricity at cheapest rates in India (and the only exception can be the farmers in some other states getting power free of charge). The situation is similar in Tamilnadu and here the average cost of supply also is lower. However the situation in other states is different as evident from that of Gujrat and Karnataka in figure 1. Figure 1: Graphical patterns of distribution of tariff and cost of supply (based on survey data) Tamil Nadu 6 6 5.5 5.5 5 5 4.5 4.5 Unit Tariff/Cost (Rs) Cost of supply / Unit Tariff Rate (Rs) Kerala 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 1 0.5 0.5 0 0 Houses in the monthly electricity consumption order Tariff Rate Houses in the monthly electricity consumption order Cost of supply Unit Tariff in Rs Gujarat 7 6.0 5.5 5.0 4.5 4.0 3.5 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 6.5 6 Tariff Rate/Cost of supply Cost of supply/ Tariff rate Karnataka Cost of supply 5.5 5 4.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 Houses arranged in the monthly electricity consumption Tariffrate Houses arranged in the order of monthly electricity consumption cost of supply Tariff Rate Cost of supply Source: Same as Table 1 e. Though the industrial and commercial consumers in Kerala have to pay a higher tariff than domestic consumers in the state, it is still cheaper than many other states (see Table A in appendix). The industrial average rate in Kerala is significantly lower than all other South Indian states. The commercial rate is also either comparable or marginally lower than many other states. f. The financial position of the KSEB has improved during the last few years. The operational losses have come down from 1200 crores Rupees per annum five years ago to around 200 crores today. It is not very difficult to wipe out the operating losses. 4 3. The factors that have contributed to the relatively comfortable position A. The previous left government had made significant investments (through borrowing) to enhance domestic generation and also to strengthen T&D network. This has contributed to the improvement of quality and availability of electricity. However these investments based on borrowed money have led to a deterioration of the financial position of the KSEB. Improvement of this financial position is the major achievement during the regime of this UDF government. B. There are a number of developments at the national level that facilitated the improvement of the financial health of KSEB. Some of these are the following: 1. The reduction in the interest rates at the national level has enabled the Board to reduce its debt burden. 2. The price reforms at the national grid, especially ABT (availability based tariff) which provide incentives for withdrawing power from the grid when the demand is lower has enabled a state like Kerala, which has some significant hydropower capacity. So KSEB could wait for times when power is cheaper at the grid by using domestic hydropower at other times. 3. Because of the threat of drastic reforms such as privatisation looming over, employees did not object vehemently to the modest organisational changes implemented in KSEB during the last four years. These changes include the abolition of a number of staff positions without any retrenchment. There was also a withdrawal of some benefits enjoyed by the employees. 4. The functioning of the regulatory commission, though have not made much headway in tariff reforms and sorting out issues related to open access, have put some pressure on the Board to reduce costs. The public discussions at the time of tariff revisions, and the evaluation of tariff proposals by the regulatory commission have enabled to bring out cost calculations of the Board into public scrutiny. Even though the financial position has improved, and the Board is able to provide relatively better quality of electricity supply, the situation can turn out to be difficult at any time. The challenges that the sector faces in the short and medium term are the following. 4. Challenges faced by Kerala's electricity sector in near future a. Though the current situation is `comfortable', this can remain there only for a short period. The increase in demand will increase the average cost of supply, because of the declining share of hydropower and the need to buy costlier thermal power. This can put further pressure on the financial position of the Board, or it will be forced to reduce the quality/quantity by not buying adequate power from the national grid. b. The subsidy distribution for domestic consumers is regressive with people consuming more power get more subsidy per month (in spite of having an increasing block tariff). This is evident from Table 3. This is due to the fact that everybody gets first 60 units or so at very low charges, which makes the average rate per unit paid by the rich and poor not as different as it would appear in increasing block tariffs. This coupled with the fact 5 that the richer sections consume more power create a situation in which they get more subsidy per annum. This situation in which one gets more subsidy as consumption increases would lead to an enhanced subsidy burden as per capita consumption goes up. This increase in subsidy burden along with the increase in average cost of supply as consumption increases (mentioned in previous paragraph), would accelerate the worsening of the financial position of the Board, if proper remedial measures are not implemented. Table 3: Distribution (%) of electricity subsidy in Indian states among different MPCE quintiles (by considering connected and unconnected households) State Year 1993-94 Andhra Pradesh 2001-02 1993-94 Bihar 2001-02 1993-94 Gujarat 2001-02 1993-94 Haryana 2001-02 1993-94 Karnataka 2001-02 1993-94 Kerala 2001-02 1993-94 Madhya Pradesh 2001-02 1993-94 Maharashtra 2001-02 1993-94 Orissa 2001-02 1993-94 Punjab 2001-02 1993-94 Rajasthan 2001-02 1993-94 Tamil Nadu 2001-02 1993-94 Uttar Pradesh 2001-02 1993-94 West Bengal 2001-02 1993-94 Assam 2001-02 Delhi 2001-02 1993-94 Himachal Pradesh 2001-02 1993-94 Jammu & Kashmir 2001-02 1-20 7.9 10.4 2.5 4.4 8.4 10 11.5 10.1 9.3 7 7.6 9.1 5.9 8.1 6.3 8.8 1.3 3.2 11.2 12.8 9.5 9 7.7 9.1 3.4 7.1 1.9 4.8 3.3 4.6 10.6 12.9 12.5 11.1 15.8 Quintiles from lowest MPCE to highest 20-40 40-60 60-80 80-100 13.5 18.4 25.4 34.8 15.6 19 24.2 30.8 3.2 9.6 25.9 58.8 10.7 18.3 26 40.6 13 17.9 25 35.8 17.9 21.4 25.8 24.8 16.7 20.7 24.1 27.1 15.9 21 21.9 31.1 14 20.7 28.5 27.5 12.5 18.6 28.7 33.1 12.6 18.4 25.1 36.1 15.2 17.2 23.7 34.7 10.9 16.9 23 43.3 16 20 25 30.9 14 20.5 24.8 34.3 15.5 19.6 21.3 34.8 6 13.5 28.3 50.9 13 18.5 31.5 33.8 14.1 18.4 22.7 33.6 19.4 20.1 24.7 22.9 14.3 20.3 21.3 34.6 14.9 22.2 25.5 28.4 12.5 17.8 25.9 36.2 13.6 19.6 24.3 33.5 8.7 14.5 22.4 51.1 12.3 17.5 24.1 39.2 7.3 14 25.5 51.2 11.4 18.5 24.1 41.2 6.4 19.3 20.9 50.2 11.1 20.2 28.4 35.5 14.9 16.4 20.2 37.7 15.7 18 21.6 31.9 16.5 22.1 21.6 27.4 15.7 17.4 24.3 31.4 19.4 21.6 21.1 22 Source: Compiled by the Author using NSS 50 th and 57th round data, and the cost of supply provided by Govt of India (2002) 6 c. Though certain austerity measures have been implemented, no major organisational reform has taken place in KSEB. Even those reforms that were agreed by the previous left government (with a profit centre approach) could not be implemented so far. Lack of any serious organisational reforms would make the Board vulnerable under any future changes in leadership, governments and policies. Election-driven populism can also bring back the Board into a crisis situation. There have been no explicit steps to give functional autonomy to the Board. Enhancement of efficiency and managerial effectiveness would require certain changes from top to bottom in the organisation. Without these changes, KSEB will continue to remain vulnerable to financial crisis, with a consequent impact on the quantity and quality of the electricity supply available to the people. d. However society is not willing to support drastic reforms such as privatisation. In our survey only 15 percent (though it is slightly higher to 25% in the cities) of the households have responded positively to privatisation in Kerala. Thus socio-political situation is such that the KSEB may continue to be a bundled state-controlled department-like entity. Under this condition, pressure on the Board to improve efficiency and service delivery has to come through political route or `voice option"(and not through competition or privatisation). With all its limitation of this voice option we have to live with it in near future. What is evident from a study of support towards privatisation in different states is that people are more willing to try privatisation and competition route as the tariff that they pay becomes closer to the perceived cost. This is indicated in Table 4. Thus one can hypothesise that once significant sections of Kerala society start paying near-cost tariffs, they would be more willing to support drastic reforms in the sector. Table: 4: Linkage between aggregate reform response in states and certain features of their electricity sector Connec Househ Average tivity olds duration consum Househol of power ing ds paying cut Oppositi Willingne more tariff (min.) on to ss to pay than more than per day Improvement privatisa more for 150 Rs. 2.50/ during last tion electricity units unit three years States Bihar Madhya Pradesh Karnataka Uttar Pradesh Rajasthan Haryana Tamil Nadu West Bengal Kerala Andhra Pradesh Orissa Low Low High High Low High Low Medium Low Medium Low Medium High Low High Low High Low High Low 20.3 Perception Percentage of change of in tariff households change in with relation to Irrigation quality Shop connection 17 74 17.2 NA 2.8 NA 1013 738 Worsened Worsened Fair Unfair 2.6 1.4 0.7 22.9 85 43 47 94 83 49 80 84 1.2 28.2 0.0 28.0 34.9 51.6 38.6 13.5 31.0 96.3 56.3 100.0 93.8 1.4 68.5 6.0 33.9 8.1 247 645 183 418 21 38 73 281 94 Improved Worsened No change No change Improved Improved No change Improved Unfair Unfair Unfair Fair Fair Fair Fair Unfair Fair 3.0 7.9 17.9 3.5 6.2 15.9 9.7 7.4 36.4 18.4 0.9 6.3 13.0 18.0 0.3 9.7 16.8 0.5 Source: Compiled by the author based on the insights from the primary survey conducted in 2005. 7 e. The experience with the regulatory commission is somewhat mixed. They have been successful to bring in tariff proposals to public scrutiny, and impose downward cost corrections in final tariff orders. However, SERC has not been much effective in restraining the blocking strategies of the Board in terms of having limited open access, in ensuring that government compensate the losses, and also in reducing cross subsidies. This is not so uncommon in other Indian states. However there is a larger issue here. When the majority of domestic consumers get electricity at subsidised rates, and this is paid through cross subsidies or government compensation, there is all incentives for the government to meddle with the affairs of the regulatory commission. Thus independent and effective functioning of SERC too depends on the removal of subsidies for the non-poor sections of the society. 5. Policy Suggestions 1. Though we need to be concerned about state-level generation capacity, too much focus on state-level generation can be a problem in the current context. Of course, it is OK if we can have more installed capacity of hydropower. But we have to be more realistic in this regard. On the other hand, excessive capacity building within Kerala through thermal generation may be costlier than buying power from the national grid. This is especially so because of the current practice of availability-based pricing in the national grid. Thus we have to tune our generation planning with national generation investments. This is important since central government is planning massive investments in energy sources such as nuclear power. 2. Limiting electricity subsidy only to poor and lower middle classes and to basic consumption should be seriously pursued, if we want to ensure the viability of KSEB. One can show that around Rupees 120 crores are given to upper 20 per cent of the households in Kerala for their annual electricity consumption. Thus there is enough scope for reducing the overall subsidy burden without burdening poor and lower middle classes. 3. Since there has been some improvement in the financial position of the KSEB, it is better to build on this improved position. Further policy and organisational changes in KSEB should not lead to a worsening of its financial position. 4. Though electricity demand would increase as investments go up, there may not be a rapid increase in demand in immediate future. This is especially so if we move towards reasonable prices. This factor should be taken into account in generation planning and in the signing of PPAs. Otherwise we may end up in a situation in which EB has to pay for fixed costs without actually taking power. To some extent we have seen that happening in the case of Kayamkulam power station. 5. Though we all agree that there should be more autonomy to the EB, and EB should manage its affairs more effectively and efficiently, how to achieve these is a million dollar question. Here we should understand that all past efforts to make these changes were not successful. Though we need not carry out unbundling and privatisation, making KSEB a state-owned company is an option worth exploring. We need to think about some structural changes to give functional autonomy and also to have a managerial culture in the organisation throughout. As we all know simply talking about autonomy and proper management have not yielded much results. Fixing responsibility and providing incentives/disincentives to individual employees/officers are unavoidable. 8 6. Though the establishment of regulatory commission was not to the liking of many, this should be effectively used by the society to instil efficiency measures on the utility. This would require strengthening (rather than weakening of) regulatory commission, and appointment of its members needs to be made without political considerations. Similarly efforts should be made to use penalties on EB (as being proposed by SERC) if it fails in terms of service delivery and for inordinate delays in responding to line faults. 7. ANERT5's (Agency for Non-conventional Energy and Rural Technology) experience of installing stand-alone solar-based electricity systems for tribal colonies located inside forests need to be analysed, and if found successful this model can be used in other localities where connection from the grid is costlier. 8. Many people have advocated the use of demand-management measures. However we should understand that one major factor that discourages consumers from adopting them is the price. That the price of electricity they pay is so cheap that they do not find the adoption of demand side measures attractive. People are aware of these possibilities. If government start providing these measures (say CFL) free or at heavily subsidised rates, these will only add to the inefficiencies in the sector. Hence the only way to encourage demand management is to have reasonable tariff for nonbasic consumption, especially for middle class and richer sections. 9. The currently prevailing tariff plans which provide very low rates for every one for their first 60 or so units create a situation in which the difference between average rates between the rich and poor not so different. This needs correction. The connection load needs to be used to differentiate between poor and non-poor and different tariff plans need to be worked out. 10. The current situation in Kerala is that the 'rent' from hydropower and the cross subsidy from industry and commerce are used for providing the subsidy to residential consumption. As I mentioned earlier those who consume more get more subsidy (in spite of increasing block tariff) because of the small difference in average rates per unit between rich and poor, and the consumption of more units by rich than poor. We have to rethink whether this rent allocation policy is the right one. For example, what about giving employment generating industry lower rates (not so low to create incentives to locate power hungry industries) than those of neighbouring states, so as to compensate for other disincentives that industrial firms face in Kerala? References: Energy Infrastructure Services Project (2000) Social and Gender Impact Assessment of power Sector Reforms in Kerala, Trivandrum: Kerala State Electricity Board Energy Infrastructure Services Project (2002), Electricity options for the poor, Madhya Pradesh State Electricity Board, Jabalpur Government of Kerala (1997), Report of the committee to study the development of Electricity (Chairman E: Balanandan). February. Thiruvananthapuram Government of Kerala (1998a), Report of the (K. P. Rao) Expert Committee to Review the Tariff Structure of KSEB, May. Thiruvananthapuram 5 Agency for Non-conventional Energy and Rural Technology 9 Government of Kerala (1998b), Organisational Self-Assessment: Reports of the Working Groups-Discussion Paper, KSEB and EISP. Thiruvananthapuram. Kannan, K.P. and N.V. Pillai (2001) Plight of the Power Sector in India, Economic and Political Weekly, January 13&20, 130-139; 234-246 Pillai, N.V. and K.P. Kannan (2001) Time and Cost Overruns of the Power Projects in Kerala, Working Paper No. 320, Trivandrum: Centre for Development Studies. Rao, M. Govinda, Shand, R. T., and Kalirajan. K. P (1998-99). 'State Electricity Boards: A performance evaluation', The Indian Economic Journal, Vol. 46 (2), October-December. Santhakumar, V. (2003a) The impact of distribution of costs and benefits of non-reform a case study of power sector reforms in Kerala between 1996 and 2000, Economic and Political Weekly, 38, 2, 147-154. Santhakumar, V. (2003b) Poverty and Social Impact Assessment of Power Sector Reforms in Kerala, Kerala Power Development Project, Asian Development Bank Santhakumar, V. (2003c) Poverty and Social Impact Assessment of Power Sector Reforms in Assam, Assam Power Development Project, Asian Development Bank World Bank (2001), India: Power Supply to Agriculture, Energy Sector Unit, South Asia Regional Office, Report No. 22171-IN. World Bank, (2002), India: Power Sector Reform and the Poor, Report No. 20517-IN, South Asia Energy and Infrastructure World Bank, (2004) Country Strategy Paper for India, Washington, D.C. 10 Appendix I Table A: Percentage distribution of consumers based on tariff (per KwH) in each state States Kerala Tamil Nadu Andhra Pradesh Orissa West Bengal Uttar Pradesh Madhya Pradesh Bihar Haryana Rajasthan Gujarat Karnataka Less than Rs. 1.00 0.0 47.6 0.0 0.3 0.0 0.5 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 23.9 0.2 Rs. 1.001.50 7.2 35.4 0.2 17.1 0.3 6.3 0.0 0.0 0.2 0.0 0.5 0.0 Rs. 1.50 2.00 70.8 14.7 28.1 47.7 1.7 0.0 0.0 68.9 1.1 0.0 0.9 0.6 Rs. 2.00 2.50 16.3 0.9 38.5 27.1 32.8 47.3 0.0 31.1 4.9 0.0 2.3 2.6 Rs. 2.50 3.00 4.8 0.7 19.2 6.2 15.2 1.4 0.0 0.0 12.2 0.0 11.7 30.8 Rs. 3.00 3.50 0.6 0.0 4.7 0.6 39.4 32.9 0.0 0.0 54.1 0.6 39.8 20.9 Rs. 3.50 4.00 0.0 0.2 2.0 0.3 4.3 7.2 0.0 0.0 17.5 10.4 11.0 17.4 Rs. 4.00 + 0.4 0.5 7.3 0.6 6.3 4.5 0.0 0.0 10.0 89.0 9.8 27.4 Source: Same as Table 1 Table B: Average cost of supply and average tariff for industrial and commercial consumers SEB/Utility Andhra Pradesh Assam Bihar Delhi(DVB) Gujarat Haryana Himachal Pradesh Jammu& Kashmir Karnataka Kerala Madhya Pradesh Maharashtra Meghalaya Punjab Rajasthan(Transco.) Tamil Nadu UP(Power corp.) West Bengal Av. commercial tariff (Ps per unit) 426.00 485.68 276.60 420.00 501.00 451.14 270.00 160.00 572.12 436.40 430.64 456.39 192.13 374.81 432.00 430.77 466.72 271.31 Av. industrial tariff (Ps/unit) 441.50 447.56 362.26 427.79 476.67 477.94 275.00 135.00 480.73 226.69 437.84 208.84 208.84 306.48 395.13 395.35 482.00 352.82 Av. cost of supply (Ps/unit) 360.7 589.1 377.1 469.6 365.4 411.9 235.4 412.3 374.6 347.3 324.9 357.5 265.0 285.2 368.2 309.8 383.6 376.8 Source: Government of India (2002) 11