this resource 134.5 KB

Teach a teacher and teach a nation

By Tony Mays

Paper presented at the NADEOSA conference held at St John’s College, Johannesburg,

27-28 August, 2003.

Tony Mays is an educator/researcher employed by SAIDE and for the past 22 months has been seconded to Unisa on an 80% time basis to help manage the Unisa NPDE programme.

Tony is a former President and is current Vice-President of NADEOSA, was chairperson of the very successful 2 nd

Pan-Commonwealth Forum on Open Learning held at the ICC Durban in 2002 and has worked with a number of institutions and organisations both locally and internationally. His particular interest is the use of distance education methods for the professional in-service development of educators.

Abstract:

This paper will identify the professional development of teachers as a central thrust for the achievement of national goals in human resource development. It will explore the NPDE as a key initiative in this respect and will analyse the ways in which the management of the NPDE as a national initiative has both enhanced and hampered opportunities for collaboration. The paper will then seek to identify key requirements for successful collaboration using the Unisa

NPDE as a case study. In conclusion, the paper will outline possible areas for future collaboration including in the field of research linking RSA’s National Skills Development

Initiative and the NPDE to the broader concerns of NEPAD and ADEA.

Introduction

There is an old Chinese curse that runs “May you live in interesting times” and those of us who work in the education system are certainly living in such times! Why has all this change come about?

Consider the following quotations ...

The curriculum is at the heart of the education and training system. In the past the curriculum has perpetuated race, class, gender and ethnic divisions and has emphasised separateness, rather than common citizenship and nationhood. It is therefore imperative that the curriculum be restructured to reflect the values and principles of our new democratic society.

Foundation Phase Policy Document, DoE, 1996

The new curriculum [for FET] will overcome the outdated divisions between ‘academic’ and

‘vocational’ education, and between education and training and will be characterised not by the ‘vocationalisation’ of education, but by a sound foundation of general knowledge, combined with practical relevance. The curriculum will offer the learner flexibility and choice, whilst ensuring that all programmes and qualifications offer a coherent and meaningful learning experience.

DoE (1998:22)

1

Since the democratic elections of 1994, the restructuring of the education and training system has been one of the top priorities of education authorities. The government has acknowledged that education and training are the central activities of South African society.

Education and training impact on every family and constitute the wealth of the country. South

Africa has never had a truly national system of education and training.

For years there were separate education departments for different races, with Africans being at the bottom of the ladder in terms of provision of resources.

Per capita expenditure was highly unequal. Schools in townships and other black areas were poorly resourced and different syllabi applied to the various groups. The challenge faced by the new government was to create a system that would fulfil the vision of opening the doors of learning and culture to all. The paramount task was to build a just and equitable system which provides good quality education and training to young and older learners throughout the country. To achieve this, the Department of Education and Training published a number of policy documents with the aim of restructuring the education system. Such policies are in line with the stipulations of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996.

Mothata in Mda & Mothata, 2000, p.2.

The following table, taken from the South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) document The National Qualifications Framework and Quality Assurance (2000, pp. 5- 6), outlines the principles on which development of the education system is based together with some reflection on the majority experience (this is SAQA’s term to describe the experience that the majority of South Africans had under the previous dispensation) on these issues to date.

Principle Definition Majority experience

Integration ... ... form part of a system of human resources development which provides for the establishment of a unifying approach to education and training

... separation by race, sex, age; by mental and manual, theory and practice, academic and technical and vocational

Relevance ... ... be and remain responsive to national development needs

Credibility ... ... have national and international value and acceptance

Coherence ... ... work within a consistent framework of principles and certification

Flexibility ... ... allow for multiple pathways to the same learning ends

... little match between what is taught in schools and what is required for the world of work

... only some certificates and qualifications are accepted and recognised at international and even national levels

... little or no means to establish equivalency across programmes and providers

... no mechanisms for assessing and recognising non-formal provision or prior learning through life and work experience

2

Standards ... ... be expressed in terms of a nationally agreed framework and internationally acceptable outcomes

... varied differences in standards across different institutions, sectors, enterprises, provinces, and the fragmented national government departments

Legitimacy ... ... provide for the participation of all national

Access ... stakeholders in the planning and co-ordination of standards and qualifications

... little or no co-operation or consultation across government departments (education, training and manpower) with little co-operation across industries, enterprises or sectors and little involvement with the state who relied heavily on experts

... provide ease of entry to appropriate levels of education and training for all prospective learners in a manner which facilitates progression

... entry principally by certificate based on years of study and generally restricted by race, sex and age

Articulation

...

... provide for learners, on successful completion of accredited prerequisites, to move between components of the delivery system

... entry requirements set at provider level with large differences between providers. Change of learning interest generally meant starting again

Progression

...

...ensure that the framework of qualifications permits individuals to move through the levels of national qualifications via different appropriate combinations of the delivery system

... rather than stepping through a clearly sequenced series of outcome requirements for higher levels on a learning pathway, learners were required to attain credits and qualifications in ways specified at the particular provider

Portability ... ... enable learners to transfer their credits or qualifications from one learning institution and/ore employer to another

Recognition of Prior

Learning ...

(RPL)

... through assessment, give credit to learning which has already been acquired in different ways e.g. through life experience

... training generally sector, enterprise or even employer specific, locking learners in because there was no common recognition system

... front end education delivery system whereby learning is regarded to stop at a particular point in life thereby excluding the possibility of learning in contexts other than the formal system

Guidance of

learners ...

... provide for the counselling of learners by specially trained individuals who meet nationally recognised standards for educators and trainers

... guidance and counselling viewed as specialist services and separate from the learning system itself.

Services were only available to a minority of learners and at particular points in career development.

South Africa’s democratic government inherited a divided and unequal system of education… In each department, the curriculum played a powerful role in reinforcing inequality … [Hence the need to redesign for …]

A prosperous, truly united, democratic and internationally competitive country with literate, creative and critical citizens leading productive, self-fulfilled lives in a country free of violence, discrimination and prejudice (DoE, 1996)

DoE (2002:4)

3

As illustrated above, there has been and continues to be considerable debate about whether the education system, at all levels, is meeting the educational needs of the country. This has resulted in a proliferation of policy documents seeking to fundamentally change the way that the system is governed and managed, the way it is financed, the curriculum that is offered, the pedagogies that are employed and the ways in which learners and the system are assessed and evaluated.

It is ordinary classroom-based educators in schools and colleges who are at the forefront of all this change – hence the somewhat hackneyed but nonetheless still true assertion that heads this paper. If we cannot get basic education right; if we cannot empower educators with the competences they need to in turn empower their learners, we will continue to pour resources into a system that is fundamentally unable to meet the challenges we have identified. As noted by the Department of Education (DoE, 1998), bringing about change in educational institutions is, however, no easy matter:

Schools, in particular, serve a distinctive constituency and play a particular educational and socialising role with respect to young people. They provide a foundation of general education, as well as more specific knowledge and skills to pre-employed youth. They also tend to occupy a distinctive place in the minds of parents, young learners and educators, which reflect deep-rooted cultural roles.

For these and other reasons, changes in schooling worldwide tend to be gradual and incremental.

Colleges, on the other hand, serve a population that is generally more diverse in terms of age, occupation and field of study, and are more likely to have direct linkages with industry and employers, and to play a direct role in meeting the vocational needs of the wider community. Important differences between colleges and schools in institutional culture and ethos, in governance, management and staffing, and in programmes and curricula, have developed and entrenched themselves over time.

DoE (1998:13)

Bringing about change in these institutions means bringing about change in the people that staff them. However, many of our educators are ill-equipped for such change: many are still, after all this time, formally un(der)qualified and many more are formally qualified but practically, and motivationally, under-prepared for the enormity of the task with which they are entrusted. The National Professional Diploma in Education (NPDE) is a new qualification that seeks to address the former need. It provides lessons of experience for educator development initiatives, and not least in the area of fruitful collaboration.

1. Background to the NPDE and Unisa’s involvement

Until 1994, a distinction had always been made between the professional development of educators destined for “white” schools and those destined for schools populated by “nonwhite” learners (Welch, 2002).

4

Under the apartheid policy of separate development, it was possible for educators to begin teaching in “black” schools with a mere two years of professional development (e.g. a PTC) and sometimes with no professional qualification at all (especially where a person had obtained a matric certificate and was living in an under-resourced rural area). The extensive need for the upgrading of educator qualifications, both in terms of scale and location, can be traced back to these earlier policies.

It is not an easy matter to simply offer additional training to those educators who currently labour under the stigma of being un(der)qualified. We cannot afford to remove these educators from their classrooms and therefore need to offer a credible distance learning opportunity to these potential teacher-learners. However, in 1994, an international commission on distance education provision found, among other things, that thousands of teachers were already involved in distance education upgrading programmes of various kinds but concluded that the distance education system as a whole was largely “dysfunctional”

(SAIDE, 1994). This conclusion was reached after an analysis of the then current practice revealed that the dominant model for distance education was first generation correspondence with very limited learner support. Given that many learners were not adequately prepared for the kind of independent study that a correspondence model presupposes, it is not surprising that distance education programmes considered by the commission were characterised by high drop-out and low throughput rates. In both practice and perception, this concept of distance education provision remains prevalent (Mays, 2001) and clearly needed to be rethought if a distance education model for the NPDE were to have any impact.

In 1995, a national teacher audit was conducted (SAIDE, 1995) and found that thousands of educators were involved in numerous training programmes but that these programmes were often of questionable quality and seemed to have very little impact on the quality of classroom practice.

In 1998, a research project under the auspices of the President’s Education Initiative found that:

there was generally not a culture of reading among South Africa’s educators many educators had themselves not mastered the conceptual understandings of the learning areas they were required to teach; and

many educators were still locked into a didactic, transmission style of teaching

(Taylor and Vinjevold, 1999).

Meanwhile, during the period 1997 to 2000, a committee had been established to articulate a minimum set of norms and standards for educators and the final version of this committee’s work was gazetted as government policy in February 2000 (DoE, 2000). The Norms and

Standards for Educators policy document introduced the following ideas:

the notion of applied competence and related integrated assessment

seven roles within which educators would need to demonstrate applied competence a proposed new qualification framework with no 360 credit exit point.

The new qualifications structure proposed in the Norms and Standards for Educators policy effectively undermined the status of educators who had struggled or were struggling to complete programmes leading to an M+3/REQV13 level Diploma in Education and so the

5

Department of Education requested the Standards Generating Body for Field 05: Education,

Training and Development (SGB05) to frame an interim qualification, the NPDE, which would provide a national benchmark for a minimum REQV13 qualified teacher status but also create a pathway to REQV14 study for in-service educators who would not normally have had access to study opportunities at REQV14 level (SGB05, 2001).

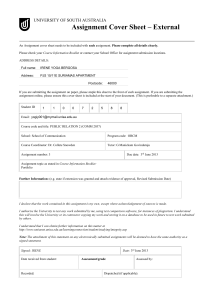

In October 2000, SAQA registered the NPDE that emanated from this process and in 2001 circulated the following revised draft qualification framework for public comment.

Table 1: NPDE in educator qualification framework

NQF Level General

Vertical articulation

Horizontal &

Diagonal articulation

Career-focused

Vertical articulation

8

(8c)

8

(8b)

8

(8a)

7

PhD

360 credits (360@8c)

Master of

Education (by research)

MEd (by research)

180 (120@8b)

MEd (structured)

180 (60@8b)

Masters Certificate

MCE

120 (120@8a)

Bachelor of Education (Honours)

BEd (Hons)

120 (120@7)

6

5

(5b)

Graduate

Certificate in

Education (GCE)

120 (96@6)

Bachelor of

Education (BEd)

[UG BEd year 4]

480 (204@6)

Professional

Diploma in

Education (PDE)

[UG BEd year 3]

360 (228@5 &

72@6)

[UG BEd year 2)

Advanced

Certificate in

Education (ACE)

120 (96@6)

National

Professional

Diploma in

Education (NPDE)

[Upgrading qualification]

240 (132@5)

5

(5a)

Certificate in

Education (CE)

[UG BEd year 1]

120 (72@5)

4 FETC

(Source: SGB05, 2001: 70)

As the table indicates, the NPDE was envisaged as a 240 credit programme primarily at NQF

Level 5. In order to access the NPDE, in-service educators would need already to have some form of initial professional qualification evaluated at at least REQV11 (e.g. Std 8/Grade 10 +

PTC/STC etc).

Taken together, the foregoing developments outlined quite specific shortcomings of previous programmes of educator development which the new NPDE qualification would need to be able to address. Since the NPDE would need to articulate with other programmes (the CE, the

BEd and the ACE), these other programmes would also need to be re-aligned.

In line with all the new qualifications proposed by the SGB for Field 5 (SGB05, 2001), the

NPDE comprises four components which correspond with the NQF’s general structure for all qualifications:

6

Fundamental Learning:

$ Component 1 (self): Competences relating to personal literacy and numeracy

Elective learning:

$ Component 2 (subject): Competences relating to the subject and content of teaching

Core learning:

$ Component 3 (classroom): Competences relating to teaching and learning processes

$ Component 4 (school and wider world): Competences relating to the school and profession.

The NPDE further requires a degree of integrated assessment that will allow for the integrated and holistic evaluation implied by the notion of applied competence specified in the Norms and Standards policy document.

Following the registration of the qualification, the Department of Education was able to secure funding to offer bursaries as an incentive to educators to enrol with the NPDE programme. The ELRC were engaged to manage the bursary process and opted for a regional model of provision. Potential providers were then invited to submit proposals to offer the programme. Unisa followed this process and was accredited as a provider during October

2001. In March 2002, Unisa was chosen as preferred provider of the NPDE to national bursary holders in Gauteng and Mpumalanga in 2002, in addition to the self-financing students who had already registered in other parts of the country.

2. The scale of the need for the NPDE

In its March 2001 Edusource Data News publication, the Education Foundation reported as follows on teacher qualifications (pp 12-13):

The total number of teachers employed by the DoE countrywide at the end of

February 2000 was 347 982. Almost 24% of teachers (85 501) are under- or un-qualified, and 80% of these teachers are in rural primary schools. Thus the

‘poorest of the poor’ in rural areas and in the least resourced provinces have the least qualified teachers. The following table reflects the geographical distribution of these teachers:

Eastern Cape

Free State

Gauteng

KwaZulu-Natal

Mpumalanga

Northern Cape

Northern Province [Limpopo]

Un(der)qualified teachers by province, 2000

18 716

6 537

4 614

20 853

5 651

1 131

10 595

North West

Western Cape

Total

14 682

2 722

85 501

7

Source: Mail & Guardian 08/12/00 reported in Edusource No. 32, p.12

Following this report, the Education Trust was commissioned to undertake a more detailed review of the need. In the final version of its report in 2001, the Education Trust concluded as follows:

According to the Persal database 2000, there were a total of 76 839 un(der) qualified educators in South Africa in 2000, who have an REQV9-12 in other words. The Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal have the highest number of un(der)qualified educators, while the North West has the highest proportion

(39,0% of its educators fall in this category). p. 1

After analysing Persal, The Education Trust sought to confirm the data by sending out survey forms to 79 631 educators (the larger number allowing for educators possibly not captured correctly by Persal):

Altogether 63 074 (79.0%) of forms were returned ... Of the 63 074 survey forms returned, only 42 565 educators were REQV 9 to 12. p. 3

The main findings of the 42 565 forms received are as follows:

67,7% have an REQV12, 19.0% have an REQV11, 8,4% have REQV10, 2,9% have an

REQV9 and about 2.0% unknown;

70,7% of the un(der)qualified educators are women;

94,3% of the un(der)qualified educators are in permanent positions;

85,8% ... of un(der)qualified educators are post level 1 educators, a total of 36 521 educators, while 5,3% (2 277) educators are heads of department, 0,8% (375) are deputy principals and

6,9% (2 974) are principals of schools.

Most of the un(der)qualified educators teach in the Foundation Phase (32,8%), followed by the Intermediate Phase (24,8%). A further 19,4% are in the Senior Phase and 7,5% are in the

Further Education and Training (FET) Phase;

55,8% (23 744) un(der)qualified educators are upgrading their qualifications;

Almost three-quarters (73,0%) un(der)qualified educators have been in the teaching profession for 10 to 29 years;

90% of un(der)qualified educators cite an African language as their home language; and

A total of 38,7% un(der)qualified educators teach mathematics, 10,9% biology and 10,0%

English.

Targeting

The largest percentage of educators un(der)qualified that need to be targeted are KwaZulu-Natal (28,5%), Eastern Cape (19,8%) and Northern Province

(15,6%). Educators need to be upgraded from REQV12 to 13 (67,7%). Special attention needs to be given to the needs of women educators (70,7%) and post level one educators (85,5%) who are either in the Foundation Phase (32,8%) or if they are specialist educators are teaching mathematics (50,4%). Educators according to home language to be targeted are isiZulu (30,7%) and isiXhosa

(19,5%). p. 4

8

3.

UNISA’s response to the challenge set by the NPDE

The fact that UNISA should attempt to address the need for large scale teacher development and upgrading through offering an NPDE was recognised during the course of 2000, as a result of the debates that flowed from the publication in February 2000 of the Department of

Education’s

Norms and Standards for Educators

(DoE, 2000) and the Department’s subsequent commitment to upgrading the competence of currently underqualified educators.

It was recognised that a large number of learners then enrolled with UNISA-SACTE and

UNISA-SACOL would fall under this category and should therefore be integrated into an

NPDE programme.

A number of informal discussions were held during the course of 2000, and a steering committee representing the three institutions in the process of merging, as well as SAIDE representation, was formally appointed during a meeting held at UNISA on 02 February,

2001, under the leadership of Prof LJ Van Niekerk.

The steering committee subsequently met on the following dates:

14 and 15 February

01 March

22 May

28 June

21 August.

As a result of these discussions, and the work that went on in between, Unisa was able to successfully meet the 31 August 2001 deadline for the submission of NPDE proposals to the

Department of Education.

The Unisa NPDE proposal, approved by the UNISA council and senate, was subsequently approved by the Interim Joint Committee of the Committee for Higher Education which was constituted for this purpose. The notion of the university as a provider of a qualification largely determined elsewhere and requiring a significant degree of face-to-face contact has introduced a new dimension into the work of Unisa’s Faculty of Education.

4. Collaboration in the NPDE: a realisable ideal?

Nominally, the NPDE is a national programme following a national curriculum.

Theoretically, therefore, with such common ground to build on collaboration should be easily possible in at least the following five key areas of operation (there may well be others):

Management and development of support and reporting systems

Marketing and advocacy

Curriculum design and materials development

Learner support

Assessment and evaluation.

It is the Unisa NPDE experience that this is much easier said than done!

9

Collaboration involves individuals and/or institutions working co-operatively together to achieve common goals, or separate goals that are complementary in one respect or another.

Fundamental to the success of a collaborative endeavour is that all parties must benefit in some way from working together. With respect to the NPDE, this has not always been possible to achieve.

4.1 Collaboration in management and development of support and reporting systems

At the macro management level, the department of education, together with the ELRC and

SACE, has led the process of introducing the NPDE at national level from requesting the design of the qualification, through to providing funding in the form of bursaries to some 11

000 NPDE learners around the country. The Department engaged the ELRC to administer the process of allocating bursaries while engaging with the interim joint committee of the

Council for Higher Education (CHE) on the evaluation of NPDE curriculum proposals.

What emerged from this process was 17 institutions accredited to offer the NPDE, with each institution or consortium interpreting the qualification somewhat differently and who proposed to develop or source learning materials, or who had already developed or sourced materials, largely independently of one another.

In October 2001, during a national workshop, it was suggested that Unisa should enter into a consortium agreement with the University of Pretoria to offer the NPDE. However, the

University of Pretoria subsequently decided not to offer the NPDE so Unisa moved ahead independently, although with the support of SACTE and SACOL who were in the process of being incorporated into Unisa at the time.

Early in 2002, Unisa attended meetings in Gauteng and Mpumalanga during which it was suggested that it should form a consortium with other potential providers. From subsequent meetings it was clear that the time and resources that Unisa had invested in developing an acceptable curriculum and in sourcing or developing the related learning materials had not been matched by its potential partner institutions and that these institutions would not be in a position to contribute to the costs already incurred. There was therefore very little foundation for a workable consortium arrangement at that late stage. A partnership with a possible private provider partner also proved untenable in terms of both the costs involved and the

DoE’s reservations about public-private partnerships at the time.

Subsequent to the meetings with Gauteng and Mpumalanga Departments of Education in

February and March 2002, Unisa became the preferred provider of the NPDE in 2002, enrolling approximately 1900 bursary students.

Regular meetings were held during the rest of 2002 and into 2003 with representatives of the two provincial departments, the national office of the DoE and Unisa, but it soon became clear that we did not always have the same understanding of the intentions of the qualification, nor the ways in which it should be delivered and assessed and there was often a mismatch between Unisa’s recording and reporting systems and those of the provincial

10

departments. Proposals to try and involve department officials at regional and district level proved difficult to get off the ground. This resulted in frustration for both the Departments concerned as well as for the Unisa NPDE programme management.

Unisa has attempted to address these concerns by adapting its operational and reporting systems in a number of respects, but this has resulted in additional costs that were not budgeted for in its initial proposal and planning.

It is the author’s sense that we are beginning to find common ground now and that there is the potential for a more valuable collaboration between the Department of Education and Unisa in taking the project forward. In Gauteng, for example, we have established a Project

Management Team with a schedule of dates for report-back meetings. However this comes at a time when national funding for the NPDE has already been exhausted!

4.2

Collaboration in marketing and advocacy

Once again the Department of Education at national level took the lead in advocating the

NPDE programme producing an information brochure which was sent to all schools in the country. However, the process of producing this brochure does not seem to have been a thoroughly collaborative process because it has proved fundamentally misleading. The national brochure talks about the NPDE as a two-year programme, which is correct, since the qualification has an NQF value of 240 credits. However 240 credits is equivalent to two years of full-time study whereas the NPDE is aimed at educators who are in full-time employment and cannot possibly commit to the equivalent of full-time study at the same time. This has put pressure on providers to try to get everybody through the qualification in the minimum twoyear period through an RPL process. However, funding has not been made available for this purpose. In Unisa’s case, the existing RPL policy is too rigorous, time-consuming and costly to meet the needs of the NPDE challenge.

A key characteristic of distance education provision is the high up front costs of curriculum and materials development and the establishment of learner support systems, costs which are then amortised over a period of time and large student numbers. The Open University UK has, for many years, for example, seen 1000 learners as a key benchmark to justify the development of a distance education programme. This recognises that it is important to be able to recruit students in sufficient numbers to be able to reap the economies of scale that distance education in principle makes possible.

With regard to the NPDE we now have a situation where there have been preferred providers in each province, not always with the kind of student numbers required to justify the cost of offering the programme. Unisa has found, for example, that current student numbers in the senior phase do not really justify the cost of developing the senior phase learning materials and that the decentralised contact sessions which are an integral part of the programme are not cost-effective. Unisa has to recruit more senior phase learners or stop offering senior phase options. Up to this point, however, it has been reticent to aggressively market in provinces where it is not the preferred provider. The way in which the national bursary process was implemented meant that a student who wished to receive a national bursary

11

would have to study with the preferred provider for that province. Students who chose to register with Unisa instead were forced to pay their own study fees. With these students we have referred them first to the preferred provider of their province so that they can access financial support, but now that national funding for bursaries has dried up, there is the potential for a competition for student numbers to overtake the potential of collaboration.

4.3 Collaboration in curriculum design and materials development

As noted previously, the design of the Unisa NPDE curriculum was a collaborative endeavour involving Unisa, SACTE, SACOL and SAIDE. The resulting curriculum framework has been all the richer for this varied input.

Unfortunately, Unisa was not in a position to engage with other potential providers in its curriculum design process, and subsequent engagement with these other providers suggests that we now have about 10 different interpretations of a national qualification being offered, rather than a single national programme.

One of the consequences of this situation is that it is not that easy to subsequently share materials. It is has been the Unisa experience that materials developed by other institutions, some of which are quite excellent, do not “fit” the Unisa curriculum model. This means that rather than jointly developing and sharing materials, we have found that we need to develop our own materials or purchase already developed materials so that the institution that produced them can recoup some of its material development costs. The full Unisa programme makes use of material from the ex-Natal College of Education (subsequently part of

SACOL), the University of the Free State, SAIDE, a consortium of higher education institutions in the Western Cape and Promat Colleges in this way.

Mirroring the above, two Unisa NPDE modules have been used in the Limpopo Province

NPDE programme on a royalty or flat fee basis. Unisa has received no additional support for materials development and has charged its standard undergraduate course fee for the NPDE programme at the request of the DoE at provincial and national level to keep fees low and so maximise the potential reach of the programme. This means that it is essential that other providers wishing to use the UNisa NPDE materials make some form of contribution to the development costs of these materials.

4.4 Collaboration in learner support

Due the fact that the various NPDE programmes operate largely separately from one another in separate provinces, there has not been much opportunity to share learner support experiences and resources. Even where a consortium exists, as in the Eastern Cape and

Limpopo, one’s sense as an outsider is often of separate campuses looking after students in particularly defined geographical areas rather than active and ongoing engagement and the sharing of lessons of experience between the respective institutions.

12

In Unisa’s case, collaboration on learner support has been largely limited to Unisa making use of the venues available from other providers and includes teacher centres (for use of which we do not usually pay) as well as public schools, church halls and technical/FET colleges.

During 2002, we were approached by Ba Isago University College in Botswana to assist with the professional upgrading of underqualified educators in Orapa who are employed by and work in the schools of Debswana diamond mine. Because they were employed by a private company, these teachers did not qualify for entry to the professional development programmes offered by the public institutions. Unisa’s agreement with Ba Isago involves

Unisa leading the academic and quality assurance processes, while Ba Isago University

Colleges plays advocacy, registration and logistical roles on the ground. The partnership also includes Debswana mines, who are paying the learners’ fees and, more recently, the national ministry which has endorsed the Unisa-Ba Isago alliance and offered to refund the fees of successful self-financed students from public institutions.

4.5 Collaboration in assessment and evaluation

As noted previously, the consequence of having 17 geographically demarcated providers is that there is very little opportunity or even motivation for collaboration.

However, there have been three national meetings to share ideas on how to meet the RPL challenge mentioned previously – although this remains an area in which there is little direction and even less funding on a national scale. Currently the position is that providers are required to provide evidence of a separate process for RPL assessment with a national policy on the issue due to be introduced for the next cohort of learners in 2004.

5. Concluding remarks and observations

If we are to achieve the kind of goals that we have set ourselves in meetings like the World

Education Forum in Dakar, in April 2000, and in policy discussions around NEPAD and other initiatives, then there is need for ongoing and concerted effort in the professional development of the educators who have first line responsibility for nurturing the achievement of the appropriate knowledge, skills and attitudes in our learners.

The scale of the challenges facing South and Southern Africa is such that collaboration is likely to become an increasingly important issue as we seek to meet increasing demands from already limited and strained resources.

Within this process, there is potential for meaningful collaboration, but this paper contends that this will happen only if:

Institutions who wish to collaborate meaningfully share a common vision and values and

Collaboration is built into the initial planning and budgeting stages and

All stakeholders benefit from the relationship.

13

One area in which we can help one another is in the sharing of information, research and lessons of experience. Within the current NADEOSA conference we have four workshop sessions which have been designed to try to facilitate this kind of sharing. We hope that it will be possible for some of the lessons of experience from these sessions to feed into a report currently being developed for the Association for the Development of Education in Africa

(ADEA) on critical success factors and costing of DEOL provision, with a particular emphasis on educator development. The final report will be shared with other countries and institutions with a need to meet the kind of challenges that we all share and who can possibly learn from our experiences.

Contacts: 012 429 4623 (O)

082 371 9215 (C) tonymays@mweb.co.za

Bibliography and references

Department of Education (DoE) (1996 ) Curriculum 2005: Lifelong Learning for the 21 st Century . Foundation

Phase policy document . Pretoria: DoE.

Department of Education (DoE) (1998) Education White Paper 4: A Programme for the transformation of

Further Education and Training – Preparing for the twenty-first century through education, training and work.

Pretoria: DoE.

Department of Education (2000) Norms and Standards for Educators. Government Gazette, Vol. 415, No.

20844, 04 February, 2000 . Pretoria: Government Printer.

Department of Education (DoE) (2001a) The National Professional Diploma in Education . Pretoria: ELRC,

DoE, SACE.

Department of Education/Education Foundation Trust (DoE/EFT) (2001b) The Unqualified and Under-qualified

Educators in South Africa - 2001 . Final version. Pretoria: DoE.

Department of Education (2002) C2005: Revised National Curriculum Statement Grades R-9 (Schools) –

Overview . Pretoria: DoE.

Education Foundation (2001) Edusource Data News, March 2001. Johannesburg: Education Foundation.

Mays (2001) Walking with Dinosaurs - DE: Evolution or extinction and the NPHE . Paper delivered at the

NADEOSA Conference, 2001, Wits Club, Johannesburg.

Mda, T. & Mothata, S. (Eds) (2000) Critical Issues in South African Education - After 1994.

Kenwyn: Juta and

Company.

RSA (1998) The Employment of Educators Act, Act 76 of 1998. Pretoria: Government Printer.

SGB05 (2001) Qualifications from the Educators in Schooling SGB Registered by the SAQA Board, 10 October,

2001. Field 05: Education, Training and Development, Sub-field Schooling . Port Elizabeth/Johannesburg:

SGB05.

South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). (2000) The National Qualifications Framework and Quality

Assurance.

http//www.saqa.org.za

South African Institute for Distance Education (SAIDE) (1994) Open and Distance Education in South Africa:

Report of an International Commission, January - April, 1994. Swaziland: Macmillam-Boleswa/SAIDE.

14

South African Institute for Distance Education (SAIDE) (1995) Teacher education offered at a distance in

South Africa: a report for the National Teacher Audit . Johannesburg: SAIDE.

Taylor, N. and Vinjevold, P. (Eds) (1999) Getting learning right: report of the President’s Education Initiative

Research Project . Johannesburg: Joint Education Trust.

Welch, T. (2002) Teacher education in South Africa before, during and after apartheid: an overview in Adler and Reed (Eds) (2002) Challenges of Teacher Development: An investigation of take-up in South Africa .

Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers. 17 – 35

15