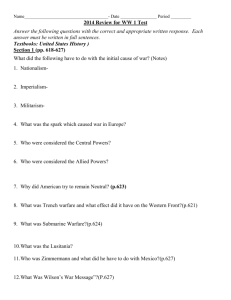

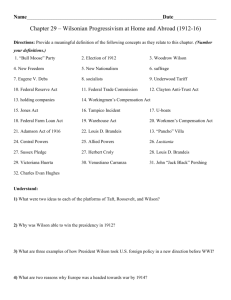

Lecture: The Great War

advertisement

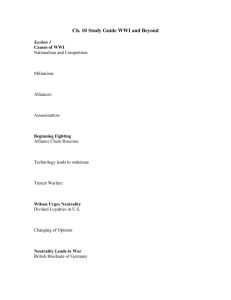

The Great War The assassination of one man (and his wife), no matter how important he was, should not have thrown the world into the worst war to that point in history. When Gavrilo Princip shot Archduke Franz Ferdinand (and his wife) in an open car in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, he set a match to a powder keg that had been smoldering for some time. The heir to the dual throne of Austria-Hungary was on a tour of Serbia trying to make the Serbs feel better about the idea of being part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Princip, a Serbian nationalist, proved that Serbia did not like the heir, the idea, or the empire. The four main causes of The Great War (World War I) were imperialism, nationalism, militarism, and a secret alliance system that was set in motion in a chain reaction after the assassination. The explosion of Europe took place in ten steps with which you should be familiar: 1. A Serb killed the Archduke. 2. Knowing it was backed by a secret alliance with Germany, Austria-Hungary delivered an ultimatum to Serbia regarding compensation. 3. Germany pledged openly to support her ally. 4. A secret alliance between Serbia and Russia was revealed based on Slavic ties. 5. The French revealed they were prepared to back Russia. 6. Germany attacked France through neutral Belgium hoping to finish them off before turning around to fight Russia. 7. The United Kingdom allied with France and Russia because Germany violated the territory of a neutral country. 8. Turkey and Bulgaria joined with Germany and Austria-Hungary in hopes of gaining territorial rewards, thus creating the Central Powers. 9. Japan and Italy joined what became known as the Allied Powers. 10. The United States pledged its neutrality hoping to trade with both sides. The last step infuriated Theodore Roosevelt who thought Wilson should have entered on the side of the Allied Powers. Many Americans pointed out, however, that through immigration we had acquired many blood ties with the Central Powers (11 million in fact). Our longer-lasting British heritage won out, however. The fact that the US was leaning toward the Allied Powers was clearly evident in statistics on trade with both sides. Whereas trade in 1914 with the Central Powers amounted to $70 million, trade with the Allied Powers was $825 million. As a stiff Allied blockade set in, trade with the Central Powers dropped by 1916 to $1.3 million. The US increased its trade with the Allied Powers to $3.2 billion by 1916, the year before we entered the war. TR would eventually get his wish, and he would eventually lose a son, Quentin, in the fighting. Wilson did not want to go to war in Europe; however, the United States became for the first time a creditor nation rather than a debtor nation, and that investment in the Allied Powers drew us closer as we sought to protect it. German submarines also provoked the US by sinking the Lusitania, a British passenger liner in May of 1915. Despite the fact that the Germans published notices in American newspapers that they were going to sink the ship, Americans boarded her and 128 were killed. The Germans suspected the Lusitania was being used to smuggle small arms to the Allied Powers, and dives done on the wreck have proved them right. Like in Mexico, before Wilson could adequately respond, the Arabic was sunk by U-Boats and two Americans were killed. Germany responded to Wilson’s pressure by giving the “Arabic Pledge,” a promise they would not sink anymore ships with Americans on board. They broke that pledge by sinking the Sussex in 1916. Americans were injured as she went down. Wilson extracted next the “Sussex Pledge” in which Germany said they would not sink anymore ships coming from America without first surfacing and warning the passengers aboard if the Allied blockade were loosened. Then something terrible happened. Woodrow Wilson was elected again to the presidency after pledging to American mothers that he would not send their sons to war in Europe. The Germans simply interpreted his mandate to maintain American neutrality as an invitation to conduct unrestricted submarine warfare. Meanwhile, back at the ranch (Mexico), a note arrived from the German Foreign Secretary, a man named Zimmermann, inviting them to divide the spoils if they would join the Central Powers and go ahead and invade the United States. The British intercepted this message which was sent as a coded telegram. Therefore the Zimmermann Note, when published in world newspapers, publicly provoked Wilson just as the Depuy de Lome letter had William McKinley before war with Spain. While Wilson stewed on this, four unarmed American merchant vessels were sunk in quick succession by German submarines. The Russian Revolution also eased the last factor causing Wilson to hesitate allying with the Allied Powers by taking out the Czar. Wilson, of course, went to Congress on April 2, 1917 and said at the end of his speech: It is a distressing and oppressive duty, Gentlemen of the Congress [I guess he didn’t see Ms. Rankin sitting there], which I have performed in thus addressing you. There are, it may be, many months of fiery trial and sacrifice ahead of us. It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own Governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free. To such a task we can dedicate our lives and our fortunes, everything that we are and everything that we have, with the pride of those who know that the day has come when America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace which she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other. Can you sense Wilson’s idealism even amidst his desperation? Both TR and Wilson were raised in Calvinist Christian homes, one Presbyterian and one Dutch Reformed. Both men thought they were predestined to have power. Wilson believed he was picked by God, therefore, to “make the world safe for democracy.” He asked Americans to take on the mantle of moral leaders of the world. They were to join the Allied Powers to make The Great War “the war to end all wars.” What Americans got was a 1 ½ -year taste of the cost of imperialism, and that was only the beginning of the sacrifices we would have to make in “The American Century.” The US Army was only 100,000 strong at the start of our involvement in World War I. A great push was launched by the first use of the “I Want You” Uncle Sam poster to recruit volunteer soldiers. When that was not enough, the US resorted to conscription. A total of four million Americans went to Europe in uniform, including the first women (in non-combatant roles). 2.5 million men and women volunteered, and 1.5 million men were drafted. Known as the American Expeditionary Force, or AEF, Americans entered combat in September of 1917 just as Russia backed out of the war leaving an urgent need for soldiers. General John J. Pershing was the commander of the AEF which fought in France, Belgium, Italy, and Russia before it was all over. “Doughboys,” a nickname perhaps taken from lumpy brass buttons that resembled dumplings, first fought in a place called Chateau-Thierry in France. The Germans knew something was different when US Marine Corps snipers began shooting them from 700 yards away. America’s largest battlefield contribution came during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive when around one million American soldiers were put into combat. Pershing insisted that Americans would fight beside Americans and not merely be inserted here and there to reinforce Allied troops. To show the new scale of modern war, this offensive saw 120,000 American casualties (killed and wounded), almost as many as the total number of soldiers who fought at Gettysburg. Soldiers from all sides in The Great War suffered heavy casualties because, again, the tactics were behind the technology. By the end of the war new implements of destruction included machine guns, tanks, hand grenades, airplanes, trucks (as supply vehicles), flame-throwers, and artillery capable of hurling projectiles over 25 miles into enemy lines. Soldiers fought from trenches while knee-deep in mud or water, but trenches could not save them from poison gas which sank down into holes in the earth. If you did not place your new gas mask on your face, you would be blinded and maybe even cough up your lungs in bloody chunks since the gas attacked mucus membranes. The United States received the fewest casualties of all combatant nations because we came in late and were instrumental in ending the war. Our 112,000 dead seemed small in comparison to Russia’s 1.7 million, Germany’s 1.6 million, France’s 1.4 million, and Britain’s 1 million dead. Our biggest contributions were not in men but in money, oil, and food. To fund the war effort the United States spent $66 billion by the November 11, 1918 Armistice. To raise this money the income tax was raised. Wilson’s rhetoric was so persuasive, though, that Americans bought $112 billion in war bonds! These are just the monetary aspects of economic mobilization. Even before American involvement in the war a Council of National Defense was created in 1915. Big-government proponents said the Council’s work was hampered by states’ rights and remaining laissez faire attitudes, but by our entry into the war the government’s message was clear—“Work or fight.” The War Department issued edicts regarding military needs, but by 1918 those needs were met abundantly and by voluntary compliance rather than by nationalization of industry. The only segment of the American economy that was nationalized was railroads, and they were given back to their owners at war’s end, thankfully. Future President Herbert Hoover proved his genius as an organizer by running the Food Administration and feeding us and our allies who could no longer grow their own food. The shipbuilders of America were turning out Liberty Ships at a rate of one every 30 days by war’s end. These ships were used to transport military personnel and supplies in vast quantities across the Atlantic. To mobilize Americans to such accomplishments, Wilson authorized the formation of the Committee on Public Information and chose Madison Avenue advertising executive George Creel to lead it. Creel used the techniques of modern advertising to “sell” the war to the people. Provocative color images used shame, patriotism, demonizing of the enemy, fear, and even sex to either attract soldiers to enlist or citizens to buy “Liberty” bonds. These images inspired emotions that unfortunately enflamed nativism, especially toward German immigrants. The Congress responded with the Espionage Act in 1917 and the Sedition Act in 1918. Eugene V. Debs, the socialist labor leader, was jailed under the Sedition Act for openly criticizing American involvement in the war. To calm other laborers of America, William Howard Taft was picked to head the new National War Labor Board which was formed to hear workers’ grievances. While awaiting resolution of their complaints, workers were urged to keep working for the war effort. Women and blacks came into the industrial work force in greater numbers than ever before since there were so many white men in Europe. Blacks also enlisted in the Army, still in segregated units. Important distinctions between World War I and World War II in these regards were that women left their jobs after The Great War when men came home while after World War II they remained in the work force. Blacks who experienced jobs off the plantations of the South in World War I migrated to the North in large numbers for the first time when those jobs were offered again during World War II. Woodrow Wilson’s idealistic rhetoric climaxed on January 8, 1918, when he spoke to Congress in what became known as the Fourteen Points Address. In the fourteen points he listed his suggestions for the post-war world. He proposed various adjustments and policies to solve the problems of individual nations, but most importantly addressed each of the four main causes of the war and proposed provisions to end their influence in the world. The first five points were 1) Open covenants openly arrived at, 2) Freedom of the seas, 3) Removal of economic barriers, 4) Reduction of armaments, and 5) Adjustment of colonial claims in the interests of subject peoples. Unfortunately because of circumstances beyond his control, and because of his own temperament, Wilson was unable to follow through with the expectations he set for himself and for the world. The 14th point was his failed attempt to spread Progressivism to the international level, otherwise known as the League of Nations. The direct consequences of the Great War included the destruction of the German economy. Wilson traveled to France to try to prevent a punitive peace, but the Treaty of Versailles of June of 1919 stripped Germany of its imperial holdings and disarmed it militarily. The treaty exacted reparations from the already crippled German nation that drove it toward the worldwide Great Depression early. The League of Nations was established, however, and the principle of collective security for member nations was Wilson’s main goal. Eleven new nations were created from four collapsed empires, and the nations who joined the League formed an alliance to protect each other from future invasion. Wilson was hailed as a savior by adoring European crowds. His welcome back home was not as warm. The US had been divided, burned out, and disillusioned by the war. The League of Nations was unpopular in the US because of our tradition of avoiding entangling alliances. Critics said the League would remove our right to independently declare war. The Old Guard Republicans led a reaction against Wilson’s globe-trotting Progressive reforms and became known as the Irreconcilables. Led by Henry Cabot Lodge, the Senate sought to compromise with the president. Wilson refused to alter his plans one iota and instead took his ideas to the American people in a national speaking tour in the style of “Back-to-the-People” Bob La Follette. Wilson’s exertions to get the American people to convince the Senate to back down broke his prestige but also his health. Wilson suffered a debilitating stroke which rendered him unable to speak or to walk for most of the rest of his presidency. He lay in bed and supposedly wrote notes that his wife conveyed to his Cabinet. Some historians think his wife merely wrote the notes herself and could have been America’s first female acting president. Wilson was not seen in public until a few months before his death when the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was dedicated at Arlington National Cemetery. He walked from a car to the site, then. The backlash against Progressivism had begun. In the Election of 1920 the Republicans swept into power with the largest margin of victory in American history. James Cox, the Democrat, received 127 Electoral votes to 404 for Warren G. Harding. Three post-war conservative Republican administrations in a row were America’s last taste of Jeffersonian republican principles, and Hoover wavered in the end as you’ll see. The Great War also placed America on the horns of a painful dilemma. Noninvolvement in world affairs, or isolationism, seemed impossible and would probably lead to disaster. Involvement in world affairs would prove expensive and uncomfortable, at least, and deadly at worst. The “war to end all wars” actually planted the seeds of a much greater conflict that dragged America back to Europe and propelled us to world leadership. We could not avoid involvement in World War II, the worst war the world has yet seen. The Great War created an economic disaster for industrialized Europe that led to the Great Depression. Hitler and the NAZI party used the economic collapse, animosity from the Treaty of Versailles, and hatred of the Jews to take power in Germany by 1932. American expenses in World War II were 8 times the cost of World War I, and our killed were four times greater. Again, those costs paled in comparison to those suffered by our allies and enemies across Europe, Asia, and Africa.