Chapter 23 Overview

advertisement

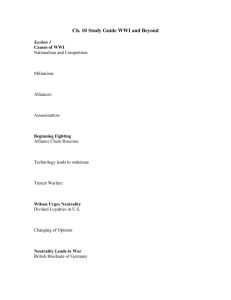

CHAPTER 23 Woodrow Wilson and the Great War CHAPTER OVERVIEW Wilson’s “Moral” Diplomacy. Wilson set the moral tone for his foreign policy by denouncing dollar diplomacy. In some matters, idealism provided an adequate basis for foreign policy. Where vital interests were concerned, however, the primacy of America’s interests outweighed Wilson’s idealism. The importance of the Panama Canal made Wilson unwilling to tolerate unrest in the Caribbean. Wilson’s most fervent missionary diplomacy manifested itself in Mexico, where his personal abhorrence of the Mexican dictator, Victoriano Huerta, led to American military intervention in Mexico’s internal affairs. Europe Explodes in War. When World War I broke out in Europe, most Americans believed that the conflict did not concern them. Wilson promptly issued a proclamation of neutrality. The war’s affront to progressive ideals, combined with the traditional American fear of entanglement in European affairs, provided ample justification for neutrality. Though most Americans wanted to stay out of the war, nearly all were partial to one side or the other. People of German, Austrian, and Irish descent sympathized with the Central Powers; the majority, however, influenced by the ties of Anglo-American culture and successful Allied propaganda, sided with the Allies. Freedom of the Seas. Anticipating the economic benefits of trading with all belligerents, the United States found Britain’s control of the Atlantic frustrating. Britain declared nearly all commodities to be contraband of war. Although British tactics frequently exasperated Wilson, they did not result in the loss of innocent lives. Therefore, Wilson never seriously considered an embargo. Given British naval superiority and the economic importance of America, any action by the United States inevitably had a negative impact on one side or the other. Ultimately, increased trade with the Allies and profits from loans to France and England tied America more closely to the Allies. In addition, Germany’s use of submarine warfare brought new questions to issues of naval warfare and neutral rights. Extremely vulnerable on the surface and too small to carry survivors, U-boats could not play by the old rules of war. The result was often a heavy loss of life. The sinking of the Lusitania (May, 1915), with the loss of 128 American lives, brought an outcry from the American public. After dragging out the controversy for nearly a year, Germany apologized and agreed to pay an indemnity. The sinking of the Sussex in 1916 produced another strong American protest, which led the Germans to promise, in the Sussex pledge, to stop sinking merchant ships without warning. The Election of 1916. Facing a unified Republican Party in 1916, Wilson sought to gain support from progressives. He nominated Lewis D. Brandeis to the Supreme Court, signed the Farm Loan Act, approved the Keating-Owens Child Labor Act and a workmen’s compensation package for federal employees, and modified his stance on the tariff. In doing so, Wilson put into effect much of the Progressive Party platform of 1912. Wilson’s maintenance of American neutrality and his progressive domestic policies won for him a narrow victory over Republican challenger Charles Evans Hughes. The Road to War. In an effort to mediate the European conflict, Wilson sent his advisor, Colonel Edward M. House, to negotiate with the belligerents. After the failure of the House mission, America moved ever closer to intervention. Europe refused to respond to Wilson’s plea in January, 1917 for peace without victory. After that, a series of events led the United States closer to war. Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in February. The Zimmermann telegram was released in March, after which Wilson authorized the arming of American merchantmen. On April 2, 1917, Wilson requested that Congress declare war on Germany. On April 6, the Senate voted 82 to 6 and the House 373 to 50 in favor of war. Mobilizing the Economy. Although America’s entry into the war assured an Allied victory, the conversion of America’s economy to a wartime footing proceeded slowly, and the war ended before much of the process was complete. Conscription did not begin to mobilize the nation’s military manpower until September, 1917. After several false starts, Wilson created the War Industries Board (WIB) to direct industrial mobilization. America was more successful in mobilizing food supplies under the leadership of Herbert Hoover, a mining engineer and former head of the Belgian Relief Commission, who was appointed to supervise agricultural production. Wartime government planning and regulation began a new era in cooperation between government and business. Workers in Wartime. The demands of a wartime economy, coupled with a shortage of labor, improved the lot of American labor. Immigration was reduced to a trickle, wages rose, and unemployment disappeared. Manpower shortages created new employment opportunities for blacks, women, and other disadvantaged groups. Blacks left the South for jobs in northern factories. While the government did act to forestall strikes, its actions also opened the way for the unionization of many previously unorganized industries. Paying for the War. The war cost the federal government about $33.5 billion, not counting pensions and other postwar expenses. Government borrowing financed over two-thirds of the war’s cost. In addition to direct loans, the sale of Liberty and Victory bonds raised millions. A steeply graduated income tax, increased inheritance taxes, and an excess-profits tax helped the federal government raise over $10.5 billion in tax monies. Propaganda and Civil Liberties. To rally public support, Wilson named George Creel to head the newly created Committee on Public Information (CPI). The CPI churned out propaganda portraying the war as a crusade for freedom and democracy. In the midst of wartime hysteria, little distinction was made between constitutionally guaranteed rights of dissent and illegal acts of sedition or treason. While Wilson sometimes spoke in defense of free speech, his actions contradicted those words. He signed the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which went far beyond what was necessary to protect the national interest. Wartime Reforms. America’s wartime experience was part and product of the Progressive Era. The exigencies of war opened the way for government involvement in many social and economic areas. A new generation of professionally educated, reform-minded individuals found employment in the federal bureaucracy, and it appeared that the war was creating a sense of common purpose that might stimulate the public to cooperate to achieve selfless goals. Women’s suffrage, economic opportunities for blacks, gains in workmen’s compensation, and prohibition were but a few of the reforms of the war era. Women and Blacks in Wartime. Women found employment in new fields during the war, but for the majority, these gains were short-lived. Traditional views of a “woman’s role,” the desire to rehire veterans, and the opposition of many unions prevented women from consolidating their employment gains. More than a half million southern blacks moved north to the booming cities between 1914 and 1919. Migrating blacks met with hostility and, on occasion, violence; however, many realized an improvement in their social and political status. Blacks who joined the armed forces served in segregated units. The majority of black servicemen were assigned to support and labor units, but many did fight and die for their country. Altogether about 200,000 blacks served in Europe. Many blacks, including W. E. B. Du Bois, hoped that their patriotism would bring political equality when the war was over. Americans: To the Trenches and Over the Top. More than 2 million Americans served in Europe. Although the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), under the command of General Pershing, reached France on July 4, 1917, American forces did not see action until the battles of Château-Thierry, Belleau Wood, and Soissons in 1918. America’s largest engagement, the drive west through the Argonne Forest, involved over 1.2 million men and proved instrumental in ending the war. In November, 1918, an armistice ended the Great War. American casualties totaled 112,432 dead and 230,074 wounded. Preparing for Peace. Although hostilities ended in November, the shape of postwar Europe had yet to be decided. The Central Powers, Germany in particular, anticipated a settlement based on Wilson’s Fourteen Points. The victors, especially England and France, found many provisions of the Fourteen Points unacceptable. Wilson journeyed to Paris and attempted to personally guide the course of the peace conference. With Wilson out of the country and preoccupied with the peace conference, the domestic political situation deteriorated. There was growing discontent over his farm and tax policies; despite its gains during the war, labor was restive. Moreover, Wilson had exacerbated his political difficulties by making a partisan appeal for the election of a Democratic Congress in 1918. Republicans won majorities in both houses, and Wilson faced a hostile Congress. The President compounded his problems by failing to appoint any leading Republicans or any members of the Senate to the peace commission, thus making it less likely that the Senate would ratify the treaty. The Paris Peace Conference and the Versailles Treaty. The “Big Four,” David Lloyd George of England, Wilson of the United States, Georges Clemenceau of France, and Vittorio Orlando of Italy, dominated the Paris Peace Conference. Far more concerned over security, war guilt, and reparations than Wilson’s goals of justice and international harmony, the European victors all but ignored his goals of open diplomacy, freedom of the seas, and national self-determination. Wilson expected that the League of Nations would make up for deficiencies in the Versailles Treaty. The Senate Rejects the League of Nations. To pacify American opponents, Wilson persuaded the Great Powers to exclude “domestic questions,” such as tariff and immigration policies and the Monroe Doctrine from the purview of the League; but this did not ensure its acceptance with Americans. Senate Republicans split into three anti-League camps. The “irreconcilables” rejected League membership on any terms. The “mild reservationists” backed membership, subject to minor revisions of the League’s charter. The majority Republican opposition, the “strong reservationists” led by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, would accept the League only if American sovereignty were fully protected. Wilson refused to yield any ground and undertook a nationwide speaking tour to rally support for the treaty. At Pueblo, Colorado, Wilson collapsed and had to return to Washington. Wilson rejected all compromise, and the Senate rejected the Treaty. The Red Scare. After the war, inflation spiraled; by 1920, the cost of living stood at twice the level of 1913. During 1919, one out of five employees engaged in strike actions. Labor unrest, fear of Bolshevism, failure to distinguish between unions and communism, economic flux, and the xenophobic tenor of wartime propaganda fostered near hysteria in postwar America and led to the phenomenon known as the Red Scare. In January, 1920, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer organized a series of raids against radicals. Of the more than 6,000 “radical” foreigners seized, only 556 proved liable to deportation. When the massive uprising that Palmer predicted for May Day, 1920 failed to materialize, the Red Scare swiftly subsided. The Election of 1920. The Democrats nominated James A. Cox of Ohio, who favored membership in the League. The Republican nominee, Warren G. Harding, also of Ohio, equivocated on the issue, despite his Senate record as a strong reservationist. Harding’s smashing victory over Cox signaled more than America’s rejection of the League. The voters’ response to Harding’s call for a return to “normalcy” suggested that Americans sought an end to the period of agitation and reform that had begun with Theodore Roosevelt.