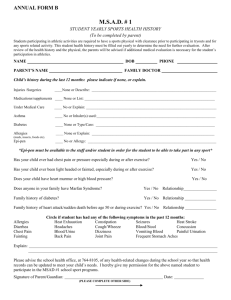

Strategic Organisation For Sport

advertisement