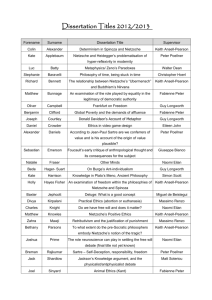

On Circassian Liberalism - dangerserviceagency.org

advertisement

Circassian Liberalism [Currently being revised for submission to Representations, June 2007] Upper Abûn, Monday, 5th June, 1837.--We staid for three days with the host at Ankhur, who demurred, and then we moved a little distance westward to the hamlet of three brothers, in a richer portion of the plain, whose clumps of stately oaks, verdant meadows, and heavy crops of corn, brought England vividly before me. Mr. L. has frequently exclaimed, “This is just like England!” --James Stanislaus Bell, Journal of a Residence in Circassia, V.1, 135. Introduction. The Circassians entered the Russian imperial imaginary as personifications of the savagery and freedom of the Caucasus. Their imagining, now as ‚free societies’, now as aristocracies, at any given time reflecting or refracting tensions in the self-perception of imperial autocracy and its elites and the project of empire than the political organization of the Circassians in reality. Inasmuch as such imaginings informed the fantasies of young men, causing them to enlist in search of the poetry of warfare, or informed the fantasies of conquest of agents of the Russian state, these imaginings became real in the consequences for Circassians. But the Russian imaginings of the Circassians were not the only ones that were of consequence in this period of the Great Game. David Urquhart, a maverick British diplomat, had become so enamored of the Circassians and their cause that he designed a national flag for a united Circassia, and attempted to provoke the Palmerston government into a war with Russia over the issue (King 2007). One of Urquhart’s legacies to Circassia were two British travelers, J. A. Longworth and James Stanislaus Bell, both of whom traveled among the Circassians for longish periods in the late 1830’s at the time of a major Russian invasion. Both these travellers (who could be described as spies, but for the fact that they represented no state) left detailed accounts which represent, perhaps, the bulk of the ethnographic information about pre-conquest Circassia. Like their Russian counterparts, there is no pretense of neutrality, though the British accounts are savage in their dismissal of the ignorance and inaccuracy of the accounts of the Russian spies who traveled the region. The main differences between the Russian and British representations of the Circassia stem directly from the different imperial projects in which they were embedded. For this reason both Russian and British accounts are singularly interested in giving an account of the Circassian political order, and for similar reasons give often entirely opposed versions of its structure and internal dynamic. Russian representations of Circassians and their institutions were contadictory, now representing fantasies of autonomy and erotic and masculine self-fulfillment characteristic of Tsarist elites, in which case the Circassians might be considered ‚free societies’, composed entirely of brigands, or now representing equally fantastic state projects for indirect rule, assuming that the Circassian social order contained within it caste divisions of nobility and serfs that could be assimilated to those of the Russian empire (Layton 1992). These British travellers, Bell and Longworth, were, on the other hand, minor quasi-private emissaries from the maverick First Secretary to British Embassy at Constantinople and confirmed Rusophobe, David Urquhart (18051877): In 1836, in order to assert the commercial right of England to trade with Circassia, [Urquhart] induced his friends the Bells, a firm of English merchants with a commercial house in Constantinople, to fit out a small ship laden with salt for a voyage to the Circassian coast. The vessel reached its destination and was for two days in trade with the inhabitants, when a Russian warship entered the harbor and seized her on the pretext of a breach of blockade. (Robinson 1920: 57) The resulting ’affair of the Vixen’ (which financially ruined the Bells) was intended to spur the Palmerston government into action. J.A. Longworth, Esq. was a correspondent for the Times in Istanbul with extensive contacts amongst the resident Caucasian communities, whom Urquhart resorted to frequently as an agent. Both Longworth and Bell were acting in Circassia in the late 1830’s much as Urquhart himself had done in 1834, as independent agents. What is remarkable about the two accounts of these two men is not merely the extremely detailed ethnographic remarks interspersed through their narratives, but the way that their failures to achieve their ends, that is, rallying the Circassians into a unified state to resist the Russians, led to more complex understandings of Circassian institutions, finally leading Longworth to attempt to see in Circassian institutions an uncanny form of Liberalism that was both strikingly familiar and yet completely strange. It was precisely the fact that they were interested actors and not disinterested observers that caused them to revise their accounts of the Circassian polity by virtue of the resistance it presented to their presuppositions and fantasies. Both men were engaged fairly directly in attempting to rally the Circassian forces against the Russians, and at the same time force the English government to assert her interests against Russia in this matter. Yet they were foiled in both directions, in England by the Palmerston government’s refusal to pursue the matter of the illegal seizure of the Vixen, on the Circassian side by the lack of any state-like political structure that they could be said to ‘represent’ in England, or ‘represent’ England to, or that could serve to unify the indubitable military strength of the Circassians in the concerted fashion needed to deal the Russians a major defeat. Of the two travellers, Bell remained convinced of the self-evident value of David Urquhart’s attempts to unify the Circassians into a state, while Longworth became increasingly skeptical that the basic presuppositions of the Circassian political order might render this impossible. From this perspective Longworth’s attempt to understand the source of the difficulties for political unification latent in Circassian political institutions is what renders his work so interesting, both his attempt to understand the Circassians in terms of the categories of liberalism, and at the same time his attempt to show the incommensurability of Circassian categories with those of liberalism. It was these two features, the combination of an attempt to see Liberalism writ large in all of the institutions of the Circasians, as well as the frustrating inability to find a political structure recognizable and manipulable in ordinary diplomatic fashion, I will argue, that make Longworth’s ethnography so interested in matters political, and, indeed, one of the more interesting attempts to understand ‘segmentary’ political systems, so-called ’stateless societies’, 100 years before Evans-Pritchard’s own attempt to do the same for the Nuer. “The misunderstanding was entirely about words”. My objective here is to show how Bell and Longworth’s interested encounter with Circassia (as agents), and their search for a Circassian polity that they could engage in a practical manner, led them into more detailed analysis of Circassian political structures, and, indeed, of the basic presuppositions of liberalism (itself a universalizing and naturalizing framework) they were using as a vocabulary of analysis. Despite repeated failure, Bell never really discarded the basic premises that he shared with Urquhart that Circassians in effect needed but a symbol to rally around, their self-evident moral unity (of language and custom) leading automatically to the formation of a polity. In Longworth’s case the frustration of their initial direct translation and transplantation led to a more complex analysis of Circassian political orders, still cast in ambivalently terms of liberalism. This allowed him to see the Circassian polity as being essentially ‚just like England’: to see in the Circassians a kind of approximation of English yeomanry, and in Circassian political structures a kind of implicit liberalism. On the other hand, it allowed him to determine what was the cause of their frustration, their concomitant inability to locate state-like structures which could be the germ of a Circassian state. At the beginning, the project of unifying the Circassians under a single government seemed quite simple and natural to both men. Bell (more of an optimist than Longworth) offers various ‘proofs’ of the moral unity of the Circassians, including language (“Adighe”) (Bell v.2 53-4), leading him to assume that such moral similarities would in due course cause them to congeal into a national cause. Longworth even arrived with a copy of the sanjak sharif, the putative flag of the united Circassia, designed by David Urquhart (and currently adopted as the symbol of Circassia). He too assumed that this object would have a self-evident value to the symbolic Circassians, as it now did for the English public who were, perhaps, the more familiar with its symbolism and purpose than the Circassians, largely thanks to the publicist efforts of David Urquhart. In fact, Longworth even used this flag itself, and the device upon it (‘white arrows and stars on a field of green silk, already familiar, I presume, to the English public as the national banner of Circassia’ (Longworth 1.67)), as an icon of his argument of the strength of a united Circassia. Ironically, he uses the symbolism of an existing flag for a not-yetexisting Circassian state to argue for the creation of that same state. For Longworth, the symbolism of the flag is as transparent and natural as the categories ‘order, union, and recognized authority’ that seemed to him to form the natural substrate of the state symbolized by this flag: I replied to him [a Circassian] in almost the same general terms that he had himself adopted; that much remained to be done on the part of his countrymen in the establishment of order, union, and a recognized authority, before any Englishman could old out hopes that his government would ever treat with, much less afford them direct assistance. It should be the aim, then, of every man who valued his country or religion to promote these objects as the only means of rescuing their necks from the impending yoke. I finished our conference…by pointing to the standard [sc. of Circassia] I had brought with me, and which, now planted on the turf before us, exhibited the device I have alluded to.... (Longworth 1.70-1) But for Circassians, the Circassian flag was no more transparent and natural a symbol than the notions of ‘order, union and recognized authority’ that it stood for. For Longworth, if not for Bell, the frustrated experience of attempting to locate state-like structures among the Circassians seems to have provoked a deeper revision of his own notion of his relations with the Circassians. The occasion for this is his discovery of a grand project of social reform emanating from within Circassian institutions, what he calls the ‘national oath’, and his own retrospective realization of the futility of engaging Circassian polities in policies and strategems that presuppose modern states, and his own subsequent revision of his own position from something like ambassador from a European state (which he never was, in any case) to something more like a witness or emissary from civilization, embodying a kind of Habermasian ‘representative publicness’, before whom one might swear a particularly solemn oath. The problem, at the outset, seemed to be one of translation: It will be my task, and no very easy one, considering its complication, to unravel the nature and progress of this reform hereafter. I now allude to it, that the reader may perceive how little at the time we understood our relative position, and how trivial the objects by which we were actuated, when compared with those that were fermenting in the minds and hearts of the Circassians. He will see also why we found it so difficult to understand each other, and why, mezzotermine, we at length came to adopting the character of ambassadors on our own account, which appeared so ridiculous to us, but was, on the contrary, so satisfactory to them. The misunderstanding was entirely about words; what they wanted was not ambassadors, but witnesses—witnesses from the civilized world, whom they sought to propitiate by a solemn abjuration of the usages that were obnoxious to it. (Longworth 1.186-8) While the other Englishmen, Mr. Bell and the mysterious aristocratic fop styled ‘Nadir Bey’ (Mr. Knight), never seem to have fully reconciled themselves to the incommensurability of their reform projects with the political institutions of the Circassians, Longworth seems to have done just that, by the curious mechanism of effecting a direct translation of Circassian institutions into familiar English liberal ones, so their difference at once becomes plain, and yet these differences are once again encompassed within the categories of English liberalism. This attempted translation was not merely linguistic, but also embedded in his pragmatic ‘projects of reform’, in which he sought to either introduce European institutions of government felt to be lacking, or seizing on the nearest equivalents that could be adapted for the purposes. Both men operated with the broad horizons of a universal liberal narrative of political progress that served as an enabling condition for their action, allowing them to see their actions as progress, and Russian imperial plans as retarding progress. Bell argues (ibid.) that the process of radical levelling discernable within Circassian society is the effects of commerce, as well as Islam, with a particularly crucial role played by technical innovations in warfare, particularly rifles, that produced a Circassian ‘hoplite revolution’ (on which see Derlugian 2007): Here, as elsewhere, the revolution which has taken place in the system of warfare, attendant upon the introduction of commerce, has contributed to produce a revolution in the grades of society….Many of the Tokavs [freemen], and even of the serfs, have become by trade (to be engaged in which is generally considered to be degrading for the other two classes) much richer than most of the nobles and princes, and therefore capable of providing means to protect themselves. To these causes of the declining influence of the aristocracy has, however, to be added…one of still greater efficacy…viz. the advocacy of the turks of an entire equality, as founded on the principles of the Koran, that all men are equal in the sight of God. (Bell 1.402-4) Russian influence, he argues, will reverse this trend, as the Circassians will become a service nobility (dvoriane), as, indeed, was the case with other nobilities in the Caucasus, such as the Georgian tavad-aznauroba caste, the Avar khans, the related Kabardians: [I]f, on the other hand, [Circassia] shall become a province of Russia, another and totally different process will commence; the power and influence of the nobles will then be revived, but their ancient basis--the respect of the people, as well as the birth-right of antique descent--will (for the process is at work in Russia) be gradually destroyed; and the good-will of the emperor, as evinced by the military rank he may confer, will become the substitute; and some future traveller will probably find in the manners of the Circassian noble, that the dignified composure and simple elegance which now characterize him have become replaced by miulitary arrogance and awkward imitation of European fashion. (1.404) At the broadest level, both men were confident that the Circassian social revolution was a species of the general leveling tendencies observable in Europe, democratization of warfare, proliferation of trade, Islam replacing Protestantism as a leveling ideology. It was then not at the level of grand narrative but at the level of specific political institutions that the practical problem of translation seemed to fail. At the beginning, Longworth admits, they had attempted to seize on the existing political structure of the Circassian council, seeing in it a parliament writ large but for its lack of permanence, and sought to rectify this by attempting to create a permanent one, among other reforms. Longworth gives a good account of the way that the seeming stolid good sense of his and Mr. Bell’s plans for introducing such a form of ‘government’ (‘measures of internal organization’ (2.27)) came to naught: The chief of these [measures of internal organization] was the establishment of a permanent council, invested with administrative authority, and a standing force, however small, for the contingencies of the campaign. Mr. Bell was also desirous of forming a corps from the Polish deserters. But these innovations, simple as they might appear, and prompted, moreover, by the necessity of the times, were such as I afterwards found involved great organic changes in the customs and social institutions of the country. The associations on which the personal security and independence of the Circassians depend, are maintained by them with a pride and tenacity which renders the introduction of any other elements of power, for national and political purposes, a matter of very great difficulty. It is true that the national councils…have, from a sense of urgent necessity, more than once been invested with paramount authority; but that it should be delegated to any particular body of individuals, or exercised for any specific period or purpose, is an idea to which they could not for a moment reconcile themselves. (Longworth 2.28) This experiment had, in fact, been tried before: at the advice of another Englishman twelve elders had formed a permanent administration at Semez: ‘finding, however, that instead of commanding respect and obedience, they were fast becoming the laughingstocks of the whole country’ (2.29), these elders returned to their hamlets to preserve whatever authority they had left. Longworth adds to the objections to renewing the experiment that there would be no remuneration for the office, nor for its ‘public’ projects, nor any means of collecting revenue or persons with the authority to do so, nor any currency in which the revenue could be collected in liquid form. All of these reasons also militated against the formation of a standing army (2.29-30), Longworth adding an even longer list of problems with Bell’s somewhat romantic proposal of a Polish corps, taking advantage of the large number of Polish slaves and refugees among the Circassians (2. 30-1), adding that Bell (himself apparently of Polish extraction) seems to have remained fascinated with the idea and unconvinced of its impracticability (2.31). Longworth adduces similar objections to Nadir Bey’s Byronesque aristocratic fantasy of attaching himself and his supplies of gunpowder to a powerful ‘chief’: Nadir Bey -- for this was the nom de guerre adopted by the [British] new-comer-was not (what I supposed he might be) an agent of the British government. He was a volunteer in the cause, a gentleman of fortune who had not even the excuse of a younger brother for seeking adventures, being impelled thereto by the genuine spirit of chivalry, which so few in this age of cold calculation can even appreciate, and of which Burke has so feelingly lamented the decline….He had not the least idea of the independence which prevails in Circassia, where, since the decline of the Pshees [princes], the chiefs have so little real power, and where every man is at liberty to take the field or remain home as he chooses, having for the most part a decided objection to fighting for anybody’s interest or amusement but his own. (Longworth 2.171-2) In order to explain the fallacies upon which these projects are based, Longworth insists that one must not make the mistake (made, for example, both by Russian imperial policy (Bell 1.404) and his fellow traveler Nadir Bey) that the local form of ‘government’ is to be found amongst the local princes. Rather, the Circassian princes represent elements inimical to both germinating state and existing society. A central point of Longworth’s analysis is that while the Circassians lack anything that could be called a state or government, yet they do not exist in a Lockean state of nature. Longworth follows a generally Lockean vision of the genesis of government, in which the formation of society is formally distinct from the formation of government, but generally the formation of society is immediately attended by the formation of government. In Longworth’s analysis, this formal distinction becomes a real distinction: the Circassians seem to have hesitated after the creation of society, and neglected to form a government. They are a stateless society. Detectable within this portion of his argument concerning the function of society without a state is a second assumption that appears here and there, which is that the Circassians lack of political institutions is in some sense what makes them liberal. This requires a particular understanding of liberal institutions as being the result of naturalizing reforms of artificial institutions bequeathed by feudal aristocratic orders. This becomes clear in his elucidation in the privileges constitutive of princely authority and distinction, where, it seems, slight differences in the order of signifiers code vast differences on the order of the signified. (It should be noted that both Longworth and Bell prefer the mannered company of princes to the rude company of the commoners whose virtues they otherwise extol). Therefore, to understand the Circassian institutions, Longworth uses names from familiar English institutions characteristic of liberalism of some form or another, even as he elucidates their substantial difference from their cognate terms. Thus, the Circassian Tokums are ‘Joint Stock companies’, Circassian councils work on a principle of ‘virtual representation’, and so on. Longworth’s argument begins with broadly Lockean premises that government is essential for the preservation of property, broadly construed, and then argues backward from this that while the Circassians do, indeed, live in a Lockean state of society, but they lack government. Moreover, so far from the former naturally giving rise to the latter, there seem to be certain ways in which the way society is constructed that render the emergence of the latter difficult. In this paper I intend to look in detail at three such comparisons of Circassian institutions that, on the one hand, Longworth considers to be possible bases on which to build a Circassian ‘government’, and which, at the very same time, represent serious obstacles to introducing ‘government’ amongst them. These are (1) the ‘feudal’ order of the princes and their privileges, inimical to both government and society, (2) the ‘societies’ or ‘tribes’, which are extraterritorial forms of organization which Longworth identifies with ‘society’, and (3) the medjilis or ‘council’ which represents the memlekhet or ‘country’, a territorial form of organization in which Longworth sees a form of ‘virtual representation’ resembling Burke’s notion of English parliamentary representation. But finally, (4) Longworth finds in the ‘national oath’ and related reforms from within that tend to unite the Circassians and ‘level’ distinctions of rank between them, as an extended analogy that both Longworth and Bell draw with the Liberal revolution in England. It is the ‘national oath’ which is the most responsive to the particular conditions of Circassia, and it is as witnesses adding ritual solemnity and publicness to this oath, rather than as purely pragmatic ambassadors from foreign states, that the Circassians value these British travelers, as Longworth finally deduces. Lords of misrule: the Circassian princes Longworth lays out his central argument on the nature of the Circassian political system in volume 1, chapter XI of his A Year among the Circassians, in a chapter entitled ‘An account of the institutions of the Circassians.’ Longworth’s point of departure is a broadly Lockean one, namely, the surprising ‘general security of life and property’ (224), contrary to expectations in the absence of a government. He contrasts the imagined state of affairs, which accentuates the Circassian in his persona, familiar from Pushkin (and generally the whole Russian imagination of Circassia), as brigand (abrek), with the empirical reality dominated by the institution which is its mirror image, the konag or ‘host’, which Longworth takes as the central guarantor of safety of life and property (‘passport’): [The stranger’s] imagination, as he wanders through its narrow defiles and gloomy forests, ‘a boundless contiguity of shade,’ would naturally people the whole with banditti, and present to him the lurking brigand at every turn and obscuration of the road. A journey of a few weeks will undeceive him; having obtained the domicile, and the name of his host, or konag, for a passport, he will encounter little danger, and meet with a cheerful welcome wherever he goes, travelling through the wilds o Circassia as unconcerned as over the most frequented thoroughfare of Europe. (224-5) Longworth notes the uniqueness of these institutions (‘they wholly differ from those which exist in any other part of the world’) as being a central warrant for his digression, as well as the fact that they had not been described before. In a methodological aside, he chides the usual ‘writers considered as authorities in this country, such as Pallas, Klaproth, or Marigny’ for their lack of mention of ‘these fundamental laws’ (225), but then, as he notes, they lack the direct empirical experience of Circassia that he, Longworth, had had over the course of a year. Even Taitbout de Marigny, who, unlike the others, had actually been to Circassia, had not had sufficient time ‘to ascertain their existence, and less to comprehend their bearing and operation’ (226). It is this lack of empirical encounter that led each of these investigators (virtually all of whom were agents of the Tsar) into their theoretical error of a priori argument, which is, essentially, to identify Circassian nobility (pshi ‘princes’, ouzdens ‘nobility’) with the functions of ‘government’: The conclusion at which all these writers have arrived, and which anybody labouring under similar disadvantages would come to when informed that there were princes and nobles in the land, is, that the peace and order established there must be owing to their administration. (226) Such a conclusion would be more amenable to existing Russian colonial policy than British insurgents, which may be some small part of why Longworth rejects it. But more compelling is his argument that, one the one hand, the identification of Circassian pshees with ‘government’ is mistaken, for ‘the authority of the Pshees, or princes, is either for good or evil actually null’ (226), and, on the other hand, where this order (still) has powers implied by the name, it ‘is rather, ...when uncontrolled by crown or crosier, an element of turbulence than security.’ (ibid.) Pillage. Longworth and Bell both note in a number of places that the princely economy, at least in their ‘palmier’ days, was an economy based to a large extent on pillage and its redistribution amongst the retainers that made this pillage possible, as well as the manipulation of blood feud systems to produce pretexts for pillage of non-princes. In fact, the ‘national oath’ along with the leveling of distinctions of blood-price between princes and non-princes were among the many reforms Longworth and Bell observed aimed at curtailing this behavior, which itself appears to have developed recently as a consequence of long distance trade (so-called ‘market-based feuds’, which have their origin on the distorting effects of economic effects on feuding institutions (Otterbein 2000)): Commerce was controlled and organized by the nobility, run by the intermediation of commercial buyers who were strangers (Turks or Tatars) installed on the coast of the Black Sea. The nobles imported manufactured goods, weapons, prestige objects, which they redistributed to their ‘vassals’....But the ‘commercial balance’ of the Circassian princes would have remained in the deficit... If they had not had another source of revenues, namely pillage. The aristocracy devoted themselves to this nearly half of the year, from spring to the end of summer , procuring thus regularly weapons, horses, slaves. This surplus allowed them to engage in exportation, especially of horses and slaves, also to entertain their vassals, an indispensable mechanism for maintaining the social structure. This complex and diversified cycle of exchanges combining agricultural production, commerce and pillage has exercised considerable influence on the Circassian vendetta, provoking distortions, ‘anomalies’, ...distortions accentuated by the very nature of political and juridical power, left to the discretion of the aristocracy. (Charachidze 1980:89) Slave trade. A particularly important ‘distorting’ effect on Circassian blood feud was the princely monopoly on foreign trade, particularly the trafficking of harem slaves to the Ottoman empire. This trade was particularly valuable to both sides, since Circassia was the last major source of harem slaves for the Ottoman empire (Toledano 1998: 31), and harem slaves were structurally central to elite politics in the Ottoman empire (Toledano ibid., other references here). While in volume the trade in Circassian harem slaves was dwarfed by African slaves (about 1000-2000 slaves per year out of some 11,000-13,000 slaves per year total in the third quarter of the nineteenth century), the Circassian slave trade was worth almost as much as the African trade (worth a total of £70,000-140,000 per year retail, compared with £160,000-200,000 for the African slave trade), because Circassian slaves, depending on their ultimate function, commanded average prices anywhere from one and a half to ten times the price of African slaves, and sometimes much more (Toledano 1982: 64-67). Given the much smaller volume of slaves and shorter transport distances, the Circassian trade in ‘prestige’ slaves accounts for a major impetus for the transition to ‘market-based’ feuding amongst coastal Circassian princes. In particular, the economy of slavery, pillage, and restribution enabled the proliferation of princely retainers, considerably augmenting the prince’s ability to continue pillaging. Therefore, the princes and their retainers are not agents of order but disorder: The will of the Pshee is a law to his followers; they do his bidding, whatever it may be; wherever he presents his rifle, a hundred are presented in the same direction; and the booty he collects in his wars is the reward of their fidelity. These petty suzerains appear to have been originally of Cabardian descent....Their object certainly appears to have been anything but the introduction of order and tranquillity where they came; and it would have been extraordinary indeed if rapacity and insolence had produced such fruits. To them, rather, the Caucasus owes its bad name; the prisoners in their wars have established a servile class in the country; and the slaves, whose beauty, in ancient and modern times, brought so high a price at Constantinople, have been at once the provocatives and the victims to their depredations. (Longworth 1.227) As a result, the Circassians seem to have identified Bell and Longworth’s proposal for ‘government’ with this princely economy of redistribution, in effect, a proposal that they should become princes themselves and so take on retainers: ‘But what use, it was asked, was a government, unless to make presents?’ (Longworth 1.108). It is also, perhaps, to facilitate a consummation so desirable, that, in seeking to place themselves under the authority of a chief, they prefer one whose resources shall be, equally with himself, of foreign derivation. It should not be forgotten, at the same time, that such crude notions of government are natural to a gallant and independent race of warriors, who have hitherto bowed to no earthly authority, and among whom it may justly be considered that a great step has been made for its [sc. Government?] establishment, in the feeling that prevails of its necessity,-proved as that necessity has been beyond a doubt by their voluntarily placing at their head any Englishman who makes his appearance on their coast. (Longworth 1.108-9) Market Based feuds. The market based feuding system not only proliferated the power of the princes, but also produced distortions in the system of vendetta. Hence, the major indigenous cause of social reform in Circassia had to do with disputes over blood price by caste. The Circassian caste system consisted of four castes. Caste endogamy was the rule. The first caste was the hereditary caste of Pshi, or ‘princes’ (as well as an even more elevated caste of khans). The second was the non-hereditary caste of noble retainers dependent on the Pshi, the Vork (warq). Together these are referred to by the Turkish appelation ouzden (lord) or bey. Alongside these are an independent caste of yeomanry comprising the bulk of the population, called in Turkish Tokav/Tocav or in Circassian Thfokotls. Lastly, the class of slaves or serfs attached to the princes, pshitl (the term appears to mean ‘prince’s man’). The primary political privileges dividing the first three castes and regulating intercaste political interactions are their relative blood prices in the blood feud system, 100 heads for a prince, 50 for a noble, 20-25 for a free man, where each ‘head’ (shxa) represents 60-80 cows (Charachidze 1980: 90). (In Longworth and Bell’s day, 100 heads for a prince, 30 for a noble, 20 (then 28) for a freeman, and 15 for a serf, finally replaced by a uniform system of 200 oxen for all but the last grade). A similar system of valuation using ‘heads’ was in operation for bride prices (‘fifty to sixty for the bride of a prince, thirty for that of a noble, and twenty five for that of a freeman’ (Bell 2.242). But this fixity of the number of heads gives an illusory sense of commensurability, for these heads also vary qualitatively in value of their composition, there being different proportions of ‘heads’ of different values for each grade: The ‘heads’ now mentioned were not however all of one value, but varied-according to the class of person whose blood had to be paid for-- from the value of sixty to eighty oxen in the case of a prince, down to eight in the case of a freeman; and among the ‘heads’ in the former case, it was specially required, that there should be sixteen young serfs of so many-- say six spans in height. Among the ‘heads’ of the other two classes there was also great variation in value according to the class. (Bell 2.242) It was precisely this ‘double’ difference in valuation, where bloodprice differs between castes not only quantitatively in a fixed geometric ratio of units but in the arbitrary qualitative value of these selfsame units, combined with the vastly superior concentrations of potentiality for violence made possible by their patronage networks, that turned the blood feud system into a ‘market-based feud’ system for which, realistically, no compensation or victory was possible against the Pshi. The only possible outcome of a feud with the princely caste was the annihilation and enslavement of the opposing group (Charachidze 1980: 90). This system was under attack during the period of Longworth and Bell, virtually always, as elsewhere in the Caucasus, by reference both to the leveling principles of Islam, as well as the leveling effects of gunpowder weapons increasingly making the heavy armor of the Pshi irrelevant (Derlugian 2007), but not the superior firepower of the princely retainers!), as well as the negative effects of Russian policies of coopting local nobility: The price of blood was formerly calculated, according to ancient usage, at so many ‘heads’ a slave, a good horse, a good shirt of mail, a good bow, sixty sheep, and so forth, being each accounted ‘a head.’ A hundred of these ‘heads’ formed the price of blood of a pshe, or prince (thaty of the descendent of a sultan was indefinite); thirty that of a vork, or noble; twenty that of a thfoktl, or freeman; and fifteen that of a pshilt, or serf. Subsequently the freemen raised the price of their blood to twenty-eight ‘heads’; and then at the suggestion of Hassan pasha (as I have formerly said) the prices of the blood of the first three classes were equalised and fixed at two hundred oxen, which are considered to amount in value to about as much as the thirty ‘heads’ which previously formed the price of blood of a noble. (Bell2.241) Retainers. A particular contention within the reforms are not so much the blood prices of princes as opposed to commoners, but more important is the differences between retainers (vork) and freemen. The vork represent a grade of distinction within the retainers of a specific prince. The status is not hereditary, unlike that of pshi, the vork are commoners by birth, promoted by the pshi: His mother belonged to the second class of vork (nobles), -- that is, those ennobled by the princes, an act which is thus performed. The prince, in presence of witnesses, presents the individual with a horse, a sabre, two oxen, and sometimes a few serfs, at the same time declaring him a vork. This class is not numerous, nor can its rank be transmitted by descent. (Bell 1.270) This class of non-hereditary retainer-nobility were the foundation of princely power, both enhancing their real power and, given that they were likely to be killed in the prosecution of princely service, their increased valuation in blood price adding a further advantage to the princes (hence the importance of limiting their differential valuation in feuds as a matter of reform). In essence, every aspect of the feuding system worked to the benefit of the princely caste (Charachidze 1980:90). Usages of courtesy. Outside of the blood feud system, relations between the Pshi (and ouzdens in general) and commoners are ambiguous and contested. The tocavs, Thfokotls, are not and were never serfs (as Klaproth believed, following a broader practice of translating directly Circassian caste distinctions into the seignorial system of the Russian empire). Rather, other than the blood feud valuation system, most of the differences between the castes resides in ‘certain usages of courtesy’ (Bell 1.408). One of these usages, important for what follows, is that precedence of seating in assembly follows rank order: ‘The descendents of Khans seat themselves on the ground first, then the Pshes, then the Vorks, and lastly the Thfokotls. Those of inferior rank always remain standing until all their superiors have set them the example of being seated.’ (Bell 1.409) Longworth echoes this assessment: But in the three provinces of Katukoitch, Shapsook, and the Abbassaks, as I have already intimated, there had been for some years past a tendency, introduced, I believe, by Mahomedanism, to level all such distinctions; and the only rights, as far as I could discover, to which persons of this class could lay claim at present are, precedence in fighting or feasting, being equally allowed the foremost place at table or in the battle field. To these prerogatives they add another, equally distinguished, that of sitting down first, and graciously permitting others to be seated after them. (Longworth 1.125-6) The Pshis, then, so far from being an explanation for the peace and security that prevails, are one which must be contained, yet without ‘crown or crosier’ intervening. Where Russian colonial policy would see in the Pshi caste or its equivalents throughout the Caucasus as potential instrumentalities for indirect rule, a service-nobility in the making, Longworth sees in the Pshi an element extrinsic and inimical to the indigenous Circassian social order, and, consonant with his own liberal attachments, sees the ‘true’ Circassian in the Circassian yeomanry. If the local aristocrats are not to serve as the basis for indigenous ‘government’, what other options existed? Circassian ‘Society’: the tribes (tokums) of Circassia The rapacity of the princes and their violent military economy of plunder and redistribution reminds Longworth of the history of the feudal aristocracy of his own land. Correspondingly, as a foil for these, Longworth sees among the ‘mutual aid’ organizations of the Circassian tribes or societies (tokums, what Bell calls ‘fraternities’, the Circassian term, according to Bell, is tleush). These ‘societies’ are extraterritorial kinship organizations which stand in opposition to the local territorial groupings (memlekhet, “the country”, “districts”, or “streams”) which are the corporate groups in which Circassians engage in warfare and in council (Longworth, Bell). The nobles do not lead these organizations, rather nobles (ouzdens, consisting of hereditary pshi and non-hereditary vorks) and commoners (tocavs, Circassian tlokothfles ) have parallel societies, often with a vague ‘alliance’ between them. The members of different Circassian societies live apart from each other, and acknowledge no leader. When a gathering takes place for an expedition or foray, the banners under which the various bands are arrayed are not those of the tribes, but of the particular districts or streams where the warriors reside. The nobles, instead of the heads of them, as some writers imagine, have their own societies as well as the freemen; all originally distinct, though sometimes connected by an oath. This sort of alliance is not uncommon; the society of nobles called Chipaquo is united to the powerful one of Tocavs, named Natquo, and from this connexion has acquired the ascendancy it enjoys in Natukvitch. It was a similar alliance with the Tocav society of Rubleh that formerly gave the [noble society of the] Abbats the same degree of influence in Shapsook. (Longworth v.1, 233-4). The societies, then, as opposed to the power of the princes and nobles, which is ‘of a military and feudal origins’ (Longworth v.1, 238), and the territorial organization of the memlekhet similarly formed ‘for warlike or national purposes’ (Longworth v.1, 238). Rather these ‘societies’ are ‘formed...not for warlike or political, but for social and judicial purposes’ (Longworth v.1, 233; also 238). Longworth believes he has discovered society amongst the various political institutions of the Circassians, that is, a form of organization that is not executive or military, but deliberative. This allows these ‘societies’ to play a crucial role in Longworth’s apologetics. On the one hand, they are ‘society’, that is, ‘social and judicial’ but not ‘military’. On the other, they are not ‘feudal’ in origin, but one might almost say, ‘civil’, since they organize all castes, not just the nobles. Continuing in the framework of the same Lockean argument with which he began his account of Circassian institutions, he more or less identifies these organizations with those functions Locke associates with the transition from the state of nature to civil or political society (the socialization of the executive function, juridical and legal institutions). In so doing, he insists that these seeming kinship groups are only fictive kinship groups, and that their real bond is one of contract. At the same time, Locke’s argument separates logically the formation of civil society (the deliberative function) from the formation of political society (delegation of the executive function, that is, socialized violence), making the former logically prior to the latter even if they seem to be historically coincident. But Longworth has discovered society without government, he has discovered ‘stateless society’ (Evans-Pritchard’s ‘acephalous kinship state’) in the Circassian institution of the ‘tribe’. Therefore, the historical role of these societies is precisely the role played by the triumphant bourgeoisie in checking the power of aristocracy in Europe. Longworth’s argument is based on a functional identity, mutatis mutandis, of the Circassian societies and the institutions of civil society founded by European bourgeoisies, the main difference being the absence of cities, towns, or locality in general, in the Circassian versions: As in Europe, under the feudal system, men of peaceful disposition and pursuits were incorporated into burghs, and townships, with a view to their common safety, so too the mountaineers, against the violence of military chiefs, have sought defense in voluntary organizations; different, it is true, but as effective, and more adapted to their mode of life and the genius of the country; associations which do not withdraw them from their fields and pastures to immure them within the walls of a city, or even confine them to a particular locality.... (Longworth V. 1, 229) Ironically, in his attempt to present these organizations as standing as bourgeois (=Tocav) ‘society’ to princely (=Pshi) military power, he neglects the fact that the princes themselves have these organizations, somewhat muddying the class basis of the opposition he is looking for. Longworth is so keen on seeing the tribes as quasi-bourgeois forms of organization more or less identifiable with Lockean ‘(civil or political) society’ that he insists on seeing them as being entirely voluntary: their kinship idiom ‘brotherhood’and rules of exogamy is for Longworth merely a fictional relationship of ‘contract’ rather than a ‘natural’ one of kinship (status) (a point important enough for him to reiterate it elsewhere 237). ...[the] sole bound of union [of these societies] is an oath, imposing, in the absence of all other ties, obligations of a most sacred character. The members of these communities all regard each other as brothers, and, to strengthen the illusion of their being such, their families are not allowed to intermarry; a regulation so rigidly observed, that even where the society is composed of many thousands, as in the case of the powerful one of Natquo, it still holds good, and a marriage between two individuals of it is looked upon as incestuous. (Longworth V. 1,229) We can see in his assessment of the central importance of the oath in the creation of these societies the germs of seeing in the institution of the oath itself the possible source for Circassian reforms. Moreover, to continue the pervasive ‘bourgeois’ feel of these societies as Longworth presents them, they can be regarded as a native form of ‘joint stock society’ (234) with ‘liberal ideas of property’ (234), in this case the stock referring to wives of deceased members, who constitute part of the ‘joint stock’ property (however illiberal the idea of property in women might otherwise have been). Since the societies are particularly involved in matters of the prosecution as well as adjudication of feuds, in which fines to be paid to the offended party are levied across the entire population of the society, and the offender is relegated to his own society for punishment (details of the function of societies in feuds are given at length, 230-233, 240ff). Every man feels that for the payment or exaction of fines the resources of the society are his own, and in proportion to these is he respected by his neighbours. Nor is this all; agreeably with the liberal ideas which prevail here generally with respect to property, and which know hardly of any bounds among the members of a society; a man has a claim upon it for anything he may stand in need of. For example, if in want of a wife, and too poor to buy one, for they are very expensive articles, his society raises a subscription for him. (Longworth v.1, 234) These institutions, particularly the role of the societies in prosecuting and adjudicating feuds, Longworth feels, are in every way beneficial to producing a sense of ‘social responsibility’ (240) amongst Circassians: In the commission of a crime, every individual is aware that it is not only against the party immediately injured he offends, but against his own society, who are all involved in its consequences, and to whom he alone is answerable for it. Revenge, on the other hand, is disarmed by the reflection that it deprives a whole society of its claim to indemnity, the exaction of which will more effectively answer its purpose, by drawing on the head of the enemy the displeasure of all his tribe. The principle here is the same as in the jurisprudence of civilized states, which makes every man responsible for his crimes to society at large; but it must be more effective when, instead of being a stranger to him, every member of that society is a brother, whose interests are immediately compromisd by his offense. (231) Having discovered a kernel of liberalism within the order of Circassian institutions, Longworth returns again to the utility of these indigenous institutions with respect to the broader program of building a Circassian ‘government’. If not the warlike bands of the princes, where can be found a Circassian basis for government? The two options seem to be, either the ‘societies’ (which Longworth identifies with ‘society’, social organization independent of political or military organization), or the territorial organization of the councils of the memlekhet (to be discussed below). Longworth is ambivalent. The societies seem to offer resistance to the very idea of a unified government: The establishment...of a supreme power would be completely incompatible with their institutions; and when the Circassians talk of it themselves, they have not the least notion that it would interfere with them....And yet to establish the advantages of a military and political organization they must submit to a government, and this would on the outset come into collision with the societies, as they would naturally object to transfer the control and punishment of their members to others, wherever they might be. (236) At the same time, the societies seem to provide a homology to some of its functions, including both internal revenue and statistics: Could this difficulty be got over with, the societies, or rather the ruins of them, would present good materials for the construction of a government. They are already in the habit of collecting property, and of equally distributing burdens for the payment of fines, and there is little doubt that the same machinery would serve for the collection of a revenue; while the statistical information possessed by every society as to its own body might also be profitably turned to account. (236) And this, finally brings us to the conclusion of the argument that Longworth began with, namely, what explains the security of life and property in Circassia. The answer, more or less, being the ‘society’ (specifically juridical institutions) represented by these ‘societies’, and not the ‘government’ of the princes, as other authors have supposed. True, Circassia itself lacks a single unifying government; rather, it consists of ‘many independent communities, commingling, yet preserving each its identity for the sake of mutual protection’ (239). At the same time, Longworth praises these institutions of the Circassians for their educative quality, and the autonomy they lend individual, which do not make the Circassian a passive client of government but an active participant: ‘there can be no doubt, in the meanwhile, that these mixed relations of society lead to a development, moral and intellectual, in the people at large, vastly superior to that which is obtained by modern civilization’ (239). The Circassians lack a single unifying government, but this does not mean that they lack the many of the civil advantages of one (defined as security of property and life), as well as all the individual ‘pride and independence’ of an armed population, that is nevertheless subject to the ‘tranquilizing effect superinduced by ...social responsibility’, producing a demeanour ‘sober and dignified’ (240): To conclude with the observations I started with; the result of these apparently conflicting elements of the social system is a harmony by no means contemptible...in no country of the world...can a stranger, after identifying himself with one of its tribes,--a privilege he obtains by becoming a guest of a member of it, who is answerable for him to the rest,--travel with greater security. (240) Virtual representation: Circassian councils It is in his discussion of the working of the Circassian councils that Longworth confronts the greatest difficulty in his project of translation. For Circassian councils lack all of the properties of a parliamentary system, there is no vote and no representation, and, indeed, no delegated bodies to which the execution of its decisions could be entrusted. How then do they produce their authority? How, in fact, do they work? Why do they exist at all? In resolving the matter, Longworth hits upon the interesting solution of deciding that they do indeed have a system of representation, a system of ‘virtual’, rather than ‘actual’ representation, here defined by its leading English exponent, the conservative writer Burke. Virtual representation is that in which there is a community of interests, and a sympathy of feelings and desires, between those who act in the name of any description of the people, and the people in whose name they act, though the trustees are not actually chosen by them. This is virtual representation. Such a representation I think to be, in many cases, even better than the actual. (Burke 1797, Works IV, 293) By these means Longworth makes an attenuated connection between the existing system (or at least highly conservative and basically anti-democratic theory) of parliamentary representation in England and the Circassian system of non-representation. In order to understand how he comes to finding a form of representation in a political system that seems to completely lack such a thing, and manages indeed to find an analog of a very conservative theory of democratic representation (which amounts to no representation at all in the ordinary sense) amongst a people who he in other respects considers to be more radical than the most radical English chartist, we must first understand how he describes the basic form and dynamic of the medjilis or council. As Longworth explains, Circassian forms of polity are characterizable in terms of the principled reasons for certain institutional absences. Circassian concepts of personal autonomy negate any possibility of representative forms of democracy, indeed, any notion of formal delegation or representation itself (Longworth 1.102-5). A direct consequence of this sense of autonomy is that at the same time any concept of voting in such a council is absolutely meaningless. Therefore the Circassian council form is, in some sense, more radical in its ‘reforms’ than English radicalism: ‘Let our radicals, who call so vehemently for universal suffrage, as the ne plus ultra of free institutions, remember that in the career of reform there is a step even beyond that—no suffrage at all’ (Longworth 1.102-5). Since liberal reformism presents itself under the sign of naturalism, progress towards freedom works in effect, backwards, and the primitive Circassians appear as the culmination of a historical progression away from artifice and towards nature. A further result is that Circassian councils, as opposed to both participatory and representative democracies, can never come to the fundamentally agonistic position of a vote (unlike Athenian democracy and English Parliament): Day after day will they resume their deliberations, while persons, whose opinions they respect, will speak for hours together; but what, no doubt, tends to prolong their sittings is, the necessity of their being unanimous—a majority on a question will not suffice to decide it; unless all are agreed, they separate without coming to any decision at all, since none will be swayed by opinions he disapproves of. (Longworth 1.125) A further consequence of this sense of absolute personal autonomy is that there can be no ‘state secrets’, everything must be ‘made public’: ‘however inconvenient the practice may appear, they allow of no secrets in the administrations of their affairs; nobody has any right to be wiser in regard to them than his neighbours (Longworth 1.123-4). By the same logic, the members of the council address the Englishmen in Circassian (which they do not know, necessitating a translator, rather than resort to Turkish which might exclude some of the participants of the council: ‘though he spoke Turkish fluently, yet, in order that all might understand our conversation, addressed us in Circassian’ (Longworth 1.116-17). Lastly, participation in the councils is in principle open to all males: ‘Everyone…has the right, if he chooses, of addressing the assembly, but it is a privilege which few avail themselves of’ (Longworth 1.124). The right to speak is freely available to all, though in practice limited to authoritative speakers, elders over 40 years (tamatas), religious authorities (effendis) and nobility (pshis). The youth (dely kanns) instead engage in a parallel and homologous set of semi-agonistic activities alongside the councils, the well-known horsemanry (djigit) of the Caucasians, or equivalently, they stand in wait for the enemies (1.102). The formal right to speak, as Longworth explains, does not include the right to command an audience: to speak without such authority is not punished in a manner akin to the demos in the form of Thersites speaking out of turn before the princes in the Homeric council scene, that is, to be clubbed into silence by the very symbol of authority, the skeptron, that symbolizes incumbency into the speaking role. Rather, the right to speak is met by an equal and opposite right to ignore a speaker, all with perfect decorum (he gives examples of this in practice elsewhere): It rarely happens that any under the age of forty ever interfere in these debates; and only with a tolerable sprinkling of grey hairs in the beard, announcing the matured wisdom of the tamatas, or elders, can the orator command attention. Should there be any individual fonder than others of hearing himself talk, they have a way of silencing him peculiar to themselves; they neither crow like cocks, nor bray like certain other animals in more civilized assemblies, but adopt a method for which the form and the roomy nature of their house of meeting, al fresco, are most peculiarly adapted. The unfortunate orator in such cases is apt to find himself with no other audience than the neighboring trees and bushes, the circle he had been addressing having rapidly dissolved and re-adjusted itself out of earshot, where it might be seen listening to somebody with better claims on its attention (1.124-5) [insert picture from Bell or Longworth of council] Therefore, the council must construct unanimity without either physical force or coercive argument. Instead, the very forms of persuasion of the council rely both on the authoritative position of the speaker and the style in which the arguments are delivered. As far as style is concerned, council meetings are divided into two rough periods. An initial period, by far the longest, in which individual speakers make their separate arguments. Here the accent is on persuasiveness (compare Caton 1987), rather than agonistic linguistic forms of argument: ‘Tumult or violence are steadily discountenanced, and the phrase they employ for eloquence, tatlu dil –literally, “sweet tongue”—marks their preference for the persuasive to the wrangling style’ (Longworth 1.124). This is the greater part of the council, involving the muted subjectivity of conciliatory persuasiveness. The following portion, after a set of unanimous propositions have been subscribed to with unanimity, involves a literal re-presentation of this unanimity of voice to the council, in a very different style, an attempt in effect to re-contextualize this discourse ‘as if’ it came as a message from elsewhere, delivered by a mounted ‘messenger’ who harangues them in stentorian voice and laconic language; by these means, in effect, they command themselves to do as they themselves have said, just as they themselves reiterate their unanimous assent by shouted amins. The medjilis met for the last time, and, as is customary at the close of the proceedings, were addressed by a mounted warrior, who rode into the midst of the assembly, and proclaimed with a loud voice the resolutions which it had unanimously come to. He then exhorted everybody present to assist, by countenance and example, in carrying them into effect. (The orator on these occasions is not expected to use tatlu dil; his language should be blunt and laconic). During the delivery of this pithy harangue, the whole assembly, at every pause made by the orator, responded, “Amin! Amin!” (Longworth 1.163-165) By these means the individual positions presented in the persuasive discourse of tatlu dil are transformed into the positions of the assembled totality and delivered as a set of laconic commands. In effect, by these means, they command themselves. The second aspect of this production of unanimity is the category of authority itself and the form of ‘virtual representation’ that lays behind it. The attendance on this occasion [of the grand council of medjilis], without being thronged…comprised the great proportion of rank, property and intelligence of the two provinces of Shapsook and Natukvitch, --the Tamatas, Effendis, and the Ouzdens—that is, the elders, judges and nobles. In short, the assembly was of a character imposing enough to confer an undeniable stamp of authority to all its proceedings. It forms, indeed, in such councils, the chief, if not only point of importance, that they should all feel convinced that they are from character and numbers so constituted as to convey an unequivocal expression of the popular will, for to none other will they submit. (Longworth 1.102) As with the use of a ‘messenger’ to command them to do what they themselves have already decided, here too they are projecting an image of authority, but also an image that they, in essence, are united as a whole. Note that Longworth is still beholden to some concept of a divide between the popular will and its representatives, even though such a divide is in essence absent, persons present at the council represent themselves, in effect, they submit to the popular will only because it is their own will However, this construction of a kind of ‘stamp of authority’ by virtue of the ‘character and numbers’ (equivalently ‘numbers and respectability’ (105)) of the council is crucial to Longworths’s notion of ‘virtual representation’. The authoritativeness of the speakers, based on the wisdom of age (tamatas), religious (effendis) or secular authority (pshis), as well as a good measure of tatlu dil, is what lends them their ability to act as ‘virtual representatives’ of the ‘popular will’, in spite of the fact that the very idea of representation and delegation is repugnant to the Circassian notion of autonomy: For the attainment of this object, it may be thought, a regular representative system would be best calculated; they prefer, however, the confusion and uncertainty which must prevail under their present mode of proceeding, to the betrayal of their interests which might result from the former. So jealous, indeed, is this sovereign people of their power, that no individual will trust his share of it out of his own hands, or even formally delegate it to any particular or any given number of representatives for a moment.…Yet, for all this sturdy independence, there can be no doubt of their being virtually represented. Age, experience, prowess, and eloquence, have all their due weight and influence, and, in adapting themselves, and assuming the garb most flattering to the prejudices of the people, render their possessors the decided organs of its opinions. (1.102-3) Virtual representation, in effect, is virtual representation without the element of delegation of power, as he clarifies himself when he speaks of a ‘delegation’ from Abbassak, and then corrects himself: Deputation I have called it, though that is hardly a proper designation for a body of individuals who, though virtually representing, as I have before explained, the part of the country from which they came, had not been formally delegated. (Longworth 1.150-1) A portion of the virtual quality simply arises from this, that the speakers were not chosen by anyone to represent the whole. The other aspect of Longworth’s theory lies in the idea that parliamentary members do not directly represent the interests of their electors or their district (as an agent represents a principle), but rather that parliament is so composed that it as a whole represents the entirety of the realm, partially by the very authoritativeness and freedom of its representatives that they are not beholden to represent the partial and local interests of their districts. Virtual representation stands to direct representation as a kind of conservative holistic theory of representation involving community of interests to a kind of theory of the whole as consisting of additive sums of partial interests. This is partially because Longworth is very interested in the idea of finding a body that might, in some sense, be able to represent Circassia as a whole, with which he and the English government might treat. In the absence of an actual system of representation, he hits upon the idea of a kind of modified virtual representation. His theory includes the idea that direct participation without such virtual representation might have been typical of councils that treated local matters (the territorial organization memlekhet ‘country’, ‘district’, ‘stream’), but with the arrival of the war with the Russians and the more extensive combinations of a segmentary logic they entailed, the councils took on a more virtual character, over a wider area: Originally this influence, like the councils in which it predominated, was in great measure confined to a particular district or tribe; but as the pressure from without, arising from Russian ambition, gave birth to more extensive combination, and to national interest, with councils on a greater scale for their direction, that influence, in seeking a wider sphere, naturally derived from the place or tribe where it was founded [ON?] a representative character. Not that any freeman in the country abandoned his right of attending those councils personally, and influencing, as far as he was able, their decisions; but that, from the inconvenience which might result from their neglect of their domestic affairs, or the assemblage of so vast a multitude of councillors on one spot, they were generally satisfied with the attendance, though not expressly sent by them, of the persons in whom they had the most confidence (105) It is from this ‘segmentary’ logic by which the presence of an external threat unified the various local forms of organization that produces the closest analog of a national parliament. From this increasingly unified council, it follows that the nature of participation will be increasingly attenuated (a familiar argument for the technical necessity of representative forms of government over participatory ones being scale), while never actually involving direct representation or delegation. That is, precisely because these quasi-representatives were chosen by no one, they cannot be ‘direct or actual representatives’. But because not everyone can attend in their own right, the fact that non-attending Circassians can be said to be ‘satisfied’, there is said to be ‘virtual representation’. Also, because virtual representation is a notion of the representation of wholes (England and the Empire) by a whole (Parliament), as opposed to direct representation, which involves the representation of partial and local interests (which act as principals) by parliamentary representatives (which act as agents), a mapping of the part to the part, so that the whole of England is represented as an aggregated sum of conflicting parts. Here, the level of combination implies that the largest medjilis has achieved ‘virtual representation’ of the warlike portions of Circassia, and this without ever so much as having a concept of representation in the first place. The National Oath The indigenous form of improving reforms, the national oath, stands at the intersection of the aforesaid orders of organization. For they are designed to curtail, in the face of the Russian advance, the economy of pillage and feud that characterizes princely distinction and for which the societies have emerged as mutual aid organizations. At the same time, they are propogated by the same councils discussed above. For Longworth, these reforms represent a natural development of the Circassian respect for oaths. Just as Longworth has reconstructed the fictive kinship of the Circassian Tleush so that it can be understood as being Society in the Lockean sense, that is, jural communities organized by oath, contract and not status, so too he has eliminated any other form of political tie from among them but this self-same oath: To explain the full power of the oath over the Circassians, which will, doubtless, appear marvellous to such as are strangers to their customs, I cannot do better than adopt their own definition or personification of it, there being about as much truth in the metaphors they employ as in any I have ever heard. Nothing, indeed, could more widely differ than the tone of affected regret, but real exultation, with which they acknowledged there was neither king nor government in the country, than the emphatic sincerity of that with which they have as often assured us that their king was their oath. It is, in fact, the monarch--the only one--whose sway (morally and metaphorically speaking) had been submitted to, from time immemorial, in every part of the Caucasus. His seal it is that confers validity on every compact, social or political. He is the mighty arbiter in all differences-- the sole lawgiver, whose authority enforced what his sanction has confirmed. All, or whatever sex or condition, are his vassals. (Longworth 2.249) Once again, the principle of contract (the oath) by which they have ‘society’ is also the only principle mediating political relations. Not even the apparent coercion of oaths from time to time (compare also King 2007) disturbs Longworth’s appraisal of the oath as being the central institution constituting the Circassian social and political order. (It is worth comparing this view to later nineteenth century evolutionists like Maine, who would perhaps be surprised to find a society founded so exclusively on ‘contract’ anywhere east of Dover). Longworth’s view, we must reminded ourselves, stands in rhetorical counterpoint to the Russian view of the Circassians, ‘invariably representing them as lawless hordes of barbarians’ (2.248): Nothing, however, could be more unfair than such statements; for though it must be admitted that the laws and institutes acknowledged by these mountaineers did not formerly interdict acts of spoliation between members of different tribes and provinces, yet the observances which they did prescribe, and which certainly sufficed for the general security of life and property, were perhaps more tenaciously adhered to than the laws are in any other country. (2.248) Unlike other projects of reform planned or projected by Messrs. Longworth and Bell, the kernel of the national oath appears, then, to arise from existing Circassian political tendencies. According to Longworth, the first form of the reform in question came with Islam, whose proselytizers sought to eliminate practices such as mutual pillage and feud, and used an early form of the national oath, having ‘invested the majesty of the oath with the more solemn insignia of the Koran’ (250). There was, however, a general reluctance to accept the oath at this time, as the civil institutions of the Circassians require the very forms of violence being renounced as sanctions: To renounce practices such as rapine and violence, the only means, as I have elsewhere explained, by which, in default of others, the tribes could obtain mutual redress, and which inferred, per se, no degree of moral turpitude, was a sacrifice few could be induced to subscribe to. (2.250-1) In order to promulgate the oath amongst recalcitrant Circassians, these early reformers resorted to indigenous forms of authority, both the authority of ‘virtual representation’ in councils discussed above, as well as, occasionally, non-lethal forms of coercion (compare King 2007): The means adopted to enforce it were in accordance with the primitive manners of the nation. A number of influential chiefs or elders, forming themselves into a body, would proceed on horseback, with a cadi or magistrate at their head, to the various streams and hamlets, and having summoned a council at each of these places, endeavour to prevail on their inhabitants to take the oath. Occasionally, when they could not be persuaded by fair means, rougher arguments were resorted to, and the disputants would take to cudgelling one another. But this sort of altercation was seldom attended with fatal results; and to characterize it more fully as a strife among brethren, it was humorously called by them ‘the war of the whips.’ (2.251-2) While these early efforts had indifferent results, with the arrival of David Urquhart in Circassia in 1834 during the Russian invasion the project was revived, particularly because Urquhart made it clear to the Circassians that renunciation of the feud and ‘the predatory habits that were the consequence of them’ was a condition for any support from England. Additionally, commerce with the Russians was interdicted in the new form of the oath (2.253). Given that the princely caste had been compromised in general by acting as konags to Russian spies, trading with and sometimes even defecting to the Russians, the content of the national oath restricting intra-Circassian pillage and trade with the Russians, like the internal measures of reform directed to the differences in blood price between castes of Circassians, must be seen as part of a general leveling tendency, a muted caste war, aimed at much at the Pshis as the Russian invaders. Under these conditions, according to Longworth, the project of the national oath took on a new vigor, and its beneficial effects as well: The effect of the oath, and the contrast afforded, during the last few years, between the sworn and unsworn districts, was almost miraculous, the former being as remarkable for the unanimity and good order which prevailed in them, as the latter were for misrule, and reckless communication with the Russians, through the neutral province of Zadoog. (2.254). It was this palpable difference then, that caused Longworth to retrospectively realize that his and Bell’s attempts represent themselves as ‘ambassadors’ in search of an indigenous form of ‘government’ constituted ‘trivial objects’, when compared to the reforms already ongoing within Circassian society itself, a project of reform eventuated both by internal caste war and Russian invasion, the national oath. Understanding the principled reasons for the success of the national oath and the failure of their own attempts to create ‘government’ not only transformed Longworth’s vision of the Circassian polity, but also transformed his perception of his own role as participant, not as ambassador from a state (which neither of them were, in any case) but as crucial witnesses before whom one might solemnly abjure such practices, hence rendering the oath effective. References Bell Burke Caton Charachidze Derlugian, 2007 Evans-Pritchard King, Charles. 2007 Layton Locke Longworth Otterbein, 2000 Robinson 1920 Toledano