MAY 2005 - Judd Commercial Lawyers

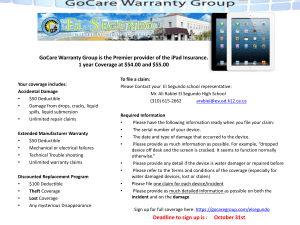

advertisement

MAY 2005 USING YOUR LEGAL EXPENSES AS A TAX DEDUCTION It is almost cliché in law, but the answer as to whether your legal costs are an allowable tax deduction depend very much on the nature of those legal costs. The general principle that applies to the deductibility of legal costs is governed by Section 8-1 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (“ITAA 97”). This section allows you to deduct losses and outgoings incurred in gaining or producing assessable income. In general you cannot deduct any losses which are of a capital nature or any losses or outgoings that relate to a private or domestic nature. Certain legal expenses can fall into very defined categories and the deductibility of these expenses is quite clear. For example, the conveyancing costs in connection with a purchase of real estate are clearly of a capital nature. Similarly any legal fees incurred in connection with the purchase or establishment of a business or other capital asset for use in a business is also of a capital nature. These are not deductible expenses. Other expenses are clearly of a revenue nature such as the legal costs involved in recovering debts owed to a business, are in fact deductible. There are also some specific provisions of the tax law which allow for certain legal expenses to be deducted. For example, legal expenses incurred in organising the borrowing of money used for the purpose of producing assessable income is a deductible expense. The legal cost of having a lease prepared for a business is a deductible expense. More specifically, Section 25-5 of ITAA allows a tax payer to claim a deduction for tax related expenses and this would include things such as the preparation of an income tax return, the disputing of a tax assessment and the obtaining of professional tax advice. D:\106753491.doc There are also certain capital legal expenses that are associated with the establishment, restructuring, defence or ceasing of a business that may qualify for a five year write off which are specifically made deductible (See Section 40-880). There are some borderline areas that may not fall under the general provisions. These are dealt with on a case by case basis by the Courts, for example:(a) The legal costs incurred for defending your business practices have been allowed as a deductible expense where it has related to the marketing practices and selling of a tax payers products or in cases where the allegations were of overcharging and unfair business practices; (b) The cost of preparing a new employment agreement with an employee is not deductible. However the costs of altering or extending an existing agreement is deductible, providing that the existing agreement allows for such changes. Any costs incurred in settling disputes arising out of employment agreements are also deductible to both the employer and the employee; (c) In general legal expenses incurred by you in defending your business or your employees from prosecutions for breaches committed in the course of carrying on your business are not deductible. However there have been some exceptions to this rule; (d) An annual retainer with a solicitor is often claimed in practice as a deductible expense and there is no attempt to allocate the costs to the various services that your solicitor may perform, some of which may relate to capital items. This is not the same for actual bill of costs for specific work performed. There are advantages in having a set annual retainer, particularly if you are able to balance the cost of the retainer against the amount of work your company or business needs. D:\106753491.doc Whilst the deductibility of legal expenses is somewhat of a grey area, what is clear is that while there are certain examples that clearly define what could be a deductible expense, where no analogous case exists, it is often arguable in the circumstances. If you are in any doubt, you should ask your solicitor or accountant in each instance whether or not the expenses incurred are actually deductible by you or your business. LIABILITY OF FORMER DIRECTORS FOR GROUP TAX On 3 May 2005, the Court of Appeal in Canty v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation upheld the District Court’s decision that a former company director can, in certain circumstances, be held personally liable for a company’s outstanding unremitted group tax. In this case, Mr Canty resigned from the board on 31 August 1999. At the time of his resignation, the outstanding unremitted company group tax was $402,917.05. Shortly after his resignation the ATO issued Notices to Mr Canty demanding that he personally pay $402,917.05 by way of a penalty pursuant to s222AOE of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (“ITAA”). Section 222AOB(1) of ITAA provides that directors are responsible for any failure by the company to remit group tax instalment deductions to the ATO on or before their due payment date. This section further provides that directors should, prior to or on the due payment date take certain steps:(i) causing the company to pay the instalments due and owing to the ATO; or (ii) to make the company reach agreement with the ATO to repay an amount equal to the unremitted group tax or in the event that the company cannot pay the unremitted group tax then (iii) appointing an administrator over the company’s assets; or (iv) begin winding up the company within the meaning of the law. D:\106753491.doc Failure to comply with section 222AOB(1) of the ITAA can render a director liable to pay the ATO by way of penalty, an amount equal to the unremitted group tax. Mr Canty denied he was personally liable to pay the penalty because he was not a director. One of Mr Canty’s arguments in his defence was that he had resigned from the board before he was served with the ATO’s Notice. As such, he was powerless to compel the company to pay the group tax to the ATO. The Court of Appeal in considering his arguments held:(a) The ITAA required the Notice need only be issued to a “person” from whom the penalty is to be recovered, which person is not necessarily a current director of the offending company; (b) Under the ITAA it is an essential condition of a director’s liability that they were in office for at least some of the period before the date on which the company became liable to payment group tax. Mr Canty was a director during this period of time; and (c) That any “harshness ….imposed on the former director under ITAA… is to some extent ameliorated by the fact that the directors cannot be sued until …Notice… is served, and by the time it has been served and a further fourteen days had passed, the director …including the former director….. will have had a period sufficient to procure the company to take one of the four steps referred in s222AB(1).” Had the company paid the ATO the unremitted group tax or placed the company into administration, or taken either of the other two steps (neither of which may have been practical within the timeframe) within fourteen days of the Notice then the penalty imposed upon Mr Canty would have been remitted. As this case illustrates, company directors must ensure that their company complies with its group tax remittance obligations and that directors need to be mindful that resigning from the board will not necessarily protect a former director from subsequent personal liability. D:\106753491.doc Contributions made by Greg Judd, Freya Jenkins, Annabel Murray, Ellen Sefton and Antonio Chan. This newsletter is provided by Judd Commercial Lawyers to guide and assist its clients and other correspondents for their information on a complimentary basis. It represents a brief summary of the law as of May 2005 and should not be relied on as a definitive, complete or conclusive statement of the relevant laws at any time. D:\106753491.doc