Arrested Development: an exploration of training and culture within

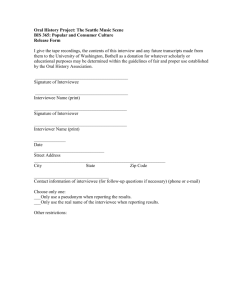

advertisement