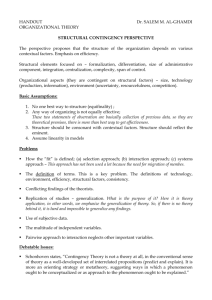

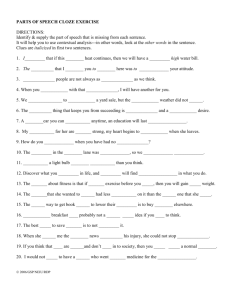

Factors influencing Performance impact of management practices

advertisement

Performance Impact of Management Practices: Explaining (Rational) Behaviour during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis1 ABSTRACT This article addresses how managing performance is itself a global crisis by examining how the performance impact of management practices is a function of senior management’s orientation and influence or contextual forces and conditions within and external to the organization. Two schools of thought are considered in this debate – managerial or leadership theories, vis-à-vis situational or contextual theories – arguing that management’s orientation and influence mediate between the contextual forces and performance impact of management practices. The observed deficiencies in the extant literature provide both theoretical and practical insights to advance knowledge about the efficacy of management practices. The paper draws on UK governmental and company examples, particularly during the 2008 global financial crisis, as empirical evidence to explicate and propose a viewpoint. It concludes to suggest that the decisions of leaders were inevitable, in that they were made (boundedly) rationally, but not necessarily optimally. Keywords: management practices/change initiatives; performance impact; failure; contextual forces; global financial crisis; performance management. Reference: ‘Proceedings of the 25th Annual Conference of the British Academy of Management (BAM), 1315 September 2011, Aston University, Birmingham, UK. 1 1 Introduction Numerous examples from a range of organizations, and from such persuasive institutions as the Institute of Personnel Management (IPM, 1993), ODPM (2001, 2003), Audit Commission (2001), ESRC (Porter and Ketels, 2003; Chau and Witcher, 2005) and CIPD (2006), assail us of moves to introduce modern operations and human resource management practices of some sort to improve quality and productivity in particular and organizational viability in general (see Ghobadian and Gallear, 1996; Worrall and Cooper, 1998; Mayer et al. 2003; Shaw and Whittington, 2003). Restructuring, delayering, downsizing, the introduction of new products and services, outsourcing, quality circles, total quality management, six-sigma, lean thinking, lean production, business process re-engineering, supply chain partnering, employee involvement, flexible working and various culture change programmes are examples of several oft-cited, widely adopted, and frequently applied operations and human resource management practices (Burnes, 2004; Coulson-Thomas and Coe, 1991; Ezzamel et al., 1994). Despite being mainstream activities and primary enablers for many organizations and the existence of anecdotal evidence of their bottom-line impact, a majority of these practices have fallen from their height of popularity (Glover and Noon, 2005), failed to live up to their promises, or have not reached their potential. It would therefore be wrong to portray these practices as effective as they were initially expected (Burnes, 2004). The literature offers ample examples of management practices that have gone wrong, some disastrously (Burnes, 2004; Kotter, 1996; Stickland, 1998), suggesting lists of long, confusing and contradictory reasons and recipes. Although understanding the major impediments to the performance impact of these practices requires an interdisciplinary investigation, each of these approaches views the low performance impact of management practices from the disciplinary angle of their originators, with the consequence of an incomplete and biased picture. So it is necessary to distinguish between core, rather than peripheral, determinants of the failures of management practices to have the intended performance impact on the organization. The 2008 global financial crisis can be viewed from the perspective of being caused by failures of poor leadership and control of the various performance management practices in use, and this offers an opportune situation with which to explore how our synthesis of the literature on the impact of management practices is an explanation of this, and if the behaviours of organizations and their leaders during this time can be considered ‘rational’. While we concur with extant views that a lack of management support of promising practices could adversely result in failing of their promises, our proposition is that failure of management practices to achieve their intended performance objectives can and should be investigated beyond a simple assertion of a lack of support and commitment due to their individual, demographic and psychological characteristics (see Hambrick and Mason, 1984; Janis, 1972; Staw et al., 1981; Miller, 1990; Brown and Starkey, 2000, Bennis and O’Toole, 2000) to encompass such mediating factors connected to the business context and 2 environment (Dess and Beard, 1984; Anderson and Tushman, 2001) and organizational ecology (Hannan and Freeman, 1977; Agarwal et al., 2002; Currie, 1999). In doing so, we base our argument on the notion of contextual factors and forces that hamper the unconditional and rational support of management to promising practices. Of contextual forces, some relate to the (internal) organizational issues, and others reflect on the organizational ecology which examines the environment in which organizations compete. The present article heeds the suggestions offered by Porter and Ketels (2003) that various organizational problems leave managers little option but to adapt themselves to the economic, social, political and institutional context in which they work. In this article, ‘management practices’, ‘management initiatives’, ‘change initiatives’, ‘change programmes’ are the interchangeable terms which refer to those practices that are planned, organization-wide, and transformational, thereby pursuing some long-term strategic objectives (see Van de Ven and Poole, 2005). We therefore do not explore and examine the nature and extent of a particular ‘management practice’ per se. Rather, we take ‘management practices’ as the frame around which the cause-and-effect relationships between contextual forces and conditions, management’s orientation and support, and the bottom-line impact and efficacy of a practice or initiative are developed and analysed. The next section of this paper explains the management practices of interest, then the section following presents the contextual forces, management orientation and explanation of impact of such practices. The paper then goes on to bring in examples as empirical evidence from the 2008 global financial crisis, and the penultimate section discusses this in the light of how such decisions during that time were rational behaviours in accordance with the literature, before concluding. Management practices: nature, scope, and impact The view that the global business world has become infected by a virus that induces a permanent need for organizational change (Sorge and Witteloostuijn, 2004) suggests a proliferation of interest in the uptake of various management practices and initiatives, particularly the importance paid to various operations management (OM) and human resource management (HRM) management practices. Most notable examples of OM practices which focus on systems management are information and communication technology, quality circles, total quality management, just-in-time, six-sigma, lean thinking, lean production, business process re-engineering, and outsourcing – to name but a few. In the same vein, HRM practices place a heavy focus on people management and employee-management relationships and involve initiatives such as training, development, teamwork, empowerment, performance appraisal and remuneration system, payment and reward system, employee involvement, flexible working, amongst others (Siebers et al., 2008). 3 At the micro level, top management of both for-profit and non-for-profit organizations have pursued an array of management practices as effective means of enhancing productivity and quality, maximising organizational performance, and simultaneously making the optimum use of the organization’s resources. At a more macro level, the adoption of these management practices is largely attributed to and being part of a far-reaching response to fierce national, regional and international competition. In addition, the adoption and operationalisation of these practices and being deeply embedded in the daily work processes and sub-processes of organizations are seen also “to impact on organizational structures and cultures including, inter alia, fewer hierarchical levels, fewer job classifications, the use of work teams, a step-change in commitment to training, and an entirely new approach to quality” (Storey, 1992, p. 1). Others take a more pessimistic view and perceive the impact of management practices (e.g. TQM) to reinforce existing power relations, hierarchical structures, organizational bureaucracy and inequality and that the existing operational and human resources practices present management with dilemmas and contradictions (McCabe, 1999). Of the most influential impact of management practices (management innovations/initiatives) is the evident degree of control that they offer to management. Taking the example of continuous improvement practices, Boje and Winsor (1993) argue that tasked based involvement at the shopfloor level is largely a method of control not least because it involves detailed specifications coming down from management which employees must implement or perfect (McCabe, 1999). Given the diverse nature of these management practices and differences in their scope and focus, Wall and Wood (2005) advocate a contingency approach to their applications and performance outcomes. They argue that while it is possible to predict a set of positive and desirable outcomes from these practices, it is rather ill-advised to suggest a ‘one size fits all’ set of productivity enhancing managerial practices. Edwards et al. (2004) led the way with their contingency hypothesis correlations between sets of managerial practices and an associated set of desirable outcomes by suggesting that the performance impact of management practices is more context-dependent and firm-specific. As they point out, the overall performance impact of both OM and HRM management practices are largely affected and influenced by the prevailing institutional environment (see Siebers et al., 2008). A set of reports published over the past several years suggests that a set of factors, seen as (dis)favourable for enhancing the performance impact of management practices, revolves around the stance taken by the top management (Storey, 1992). The argument, in simplistic terms, is that “senior management commitment to the idea is vital … [and] with it, the scepticism at lower levels can be eventually surmounted; without it, even the most well-intentioned initiatives will soon wither” (Storey, 1992, p. 43). One might suggest that the (dis)favourable performance impact of management practices is largely a function of the existence of top management support and commitment. Thus, the management support and orientation towards the adopted practices are integral to the sheer welter of management practices and their intended impact on organizational performance. 4 However, the current credit crunch of the global financial crisis usefully reminds us that even in the presence of full, unconditional support of the management team, the adopted management practices are still susceptible to undesirable outcomes and failure. An outstanding example among the panel of leading international firms which have consciously adopted and implemented just-in-time production, more famously known as the Toyota Production System (TPS) as its underlying management philosophy and practice, is that of Toyota which now faces a fate similar to its rivals Honda and Nissan, both of which have been forced to cut their full-year forecasts (Guardian Newspaper, 2008). In his account of the devastating impact of the financial crisis as well as local and global contextual forces on Toyota’s operations, the executive vice president of Toyota, Mitsuo Kinoshita, describes the current market conditions and business environment as “unprecedented”, urging: “We have encountered oil shocks and a surging Yen a number of times before, but have overcome those problems and achieved growth … The financial crisis is negatively impacting the real economy worldwide and automotive markets, especially in developed countries, are contracting rapidly … This is an unprecedented situation. It’s impossible to tell when things will start to improve.” Nor is Mitsuo Kinoshita alone in confessing to low performance impact of its internationallyrenowned TPS operations management practice largely due to the massive and potentially unprecedented environmental and contextual conditions. In response to the question of “Are we bankrupt?”, the Wall Street Journal quoted Chrysler senior manager, Robert Nardelli, replied, “Technically, no. Operationally, yes. The only thing that keeps us from going into bankruptcy is the $10 billion investors entrusted us with.” [Insert figure 1 about here] In sum, studies on performance impact of management practices suggest a number of alternative views about their impediments and enablers. On the one hand, as figure 1a shows, there would appear to be ample prima facie evidence of considerable, profound, and adversarial impact of contextual forces and conditions on the intended performance objectives of the management programmes. As figure 1b also indicates, a second and alternative stream of related research strongly views management’s capability, orientation, willingness, commitment and support as a major determinant of the efficacy of management practices in achieving their intended performance objectives. In line with these perspectives, we argue that a unified, integrated approach, linking these two streams together, helps to develop a more robust framework for and offers a more holistic view on the effectiveness and efficiency of various operations and HRM management practices. The dynamics of contextual forces, management orientation and performance impact of management 5 practices constitute the kernel of this article, around which the actions of leaders during the 2008 global financial crisis are in discussion. Contextual forces, management orientation and impact of practices Many advocates of management practices view the underlying assumptions of their proposed initiatives as universally applicable to organizations of any kind and their associated activities with virtually no attention to the nature of the uncertainty faced by the organization. The central premise of this universal view is that the principles enunciated in management practices can be utilized as a means of enhancing organizational productivity regardless of the type of the organization, the nature of their products or service offerings, or the context in which they operate. Based on the initial work of Hayes and Wheelwright (1984), the universal approach to adopting and implementing management practices has been pursued by many businesses and widely disseminated by such works as Schonberger’s (1986). This approach assists organizations to compete through the adoption of best (or world-class) practices in a wide range of areas. In the search for such a tendency towards universalism in the conceptualisation and diffusion of operations management practices (e.g. TQM initiatives), Voss (1995) elucidates three main stimuli to have brought best practices to greater prominence: (i) the outstanding performance of the Japanese manufacturing industry has led to a continuous focus in the West on identifying, and adopting Japanese manufacturing practices; (ii) the growth of business process-based approaches and benchmarking has led companies to identify their core practices and processes and to seek out best in class practice; and (iii) the emergence of operations improvement awards such as the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award (MBNQA), European Quality Award (EQA), and the Deming Prize. Despite the popularity of universal orientation towards management practices, it has received extensive criticisms not least because of its failure to take into account the peculiarities of organizations and their business environment ensued by failure of management practices to deliver their intended performance objectives. In respect of the most celebrated and widely adopted operations improvement management practices, namely TQM, Sitkin et al. (1994), for example, view the notion of TQM as universally applicable to organizations, to be in danger of being ‘oversold’ (see also Wilkinson et al., 1998). Hence, the fallacy of universal best practices, more recent rigorous academic studies have raised doubts as to the universal validity of the whole set of management practices (see Harrington, 1997). Taking the example of operations improvement initiatives, Sousa and Voss (2001) raise the possibility of quality management practices being context dependent. Four studies stand out as the main rigorous and explicit efforts in this area: Benson et al. (1991), Sitkin et al. (1994), Reed et al. (1996), and Sousa and Voss (2001). Sousa and Voss’ (2001) study, for instance, strongly suggests that process quality management practices are contingent on a plant’s manufacturing strategy, and 6 identifies mechanisms between individual process practices, forming an internally coherent quality management practice configuration matching a plant’s manufacturing strategy configuration (see also Maani, 1989; Powell, 1995; Dow et al., 1999; Ahire, 1996). Clearly, all these studies have directly or tangentially addressed the influence of context on quality management practice thus lending support for a contingency approach to TQM. As a consequence, this poses the question of whether the disappointment and dissatisfaction with TQM performance impact are due to conceptual flaws in the TQM approach or implementation deficiencies. Many proponents (e.g. Atkinson, 1990; Hackman and Wageman, 1995; Wilkinson et al., 1998; Reavill, 1999; Samson and Terziovski, 1999; Silvestro, 2001) recognise the virtues of the broad quality management model and attribute failures to implementation problems. Hence, the overall patterns that emerge from the extant literature suggest that, to quote Sitkin et al. (1994), “TQM is not a panacea that can be unthinkingly used, but that it must be implemented with a clear sense of the degree to which the context is characterised by uncertainty, nonroutineness, and or instability” (p. 538). Such observations are also echoed by Wilkinson et al.’s (1998) argument that: “the success or failure of quality management initiatives may have more to do with organization-specific factors, particularly the extent to which initiatives are implemented in a strategic manner with continuing management commitment, than with sectoral factors” (p. 183). Accordingly, the universal orientation of operations management practice such as TQM has been pointed out as contrasting with the contingent approach of management theory in general (Dean and Bowen, 1994; Sitkin et al., 1994). The underlying assumption of contingency perspective to adopting and implementing management practices hinges on the idea that management practices and their associated assumptions should be matched appropriately to contextual and situational requirements. Failing to do so will result in the loss of the potential contributions of management practices. Within the contingency approach, enhancing performance impact of management practices requires both structures and process characteristics that fit the degree of uncertainty in their environment (Duncan, 1972; Miller, 1992; Sila, 2007). Contingency or contextual variables form the context in which an organization functions and are divided into internal and external forces. Depending on the academic discipline, organizational scholars have utilised a range of different constructs as a means to operationalise internal and external contextual factors. In his study of the effects of contextual factors on operations improvement practices such as TQM and overall organizational performance, Sila (2007), for example, used organizational size and scope of operations (i.e. domestic operating versus international operating firms) as contingency or contextual factors. Within the domain of health care quality management, previous studies used centralisation of decision making, formalisation of regulations, and organizational size as their contingency or contextual factors (Wagner et al., 2001; Homburg et al., 1999). Overall, internal forces include the degree of specialisation or work specificity required by existing technology, level of organizational slack, experiences with previous changes, the culture of the organization, individual interests and 7 characteristics of the managers, the power position or status characteristics of managers, structural source of power, and compatibility of power and influence structures. External forces represent situational characteristics usually exogenous to the focal organization or manager. These forces seem to be rather uncontrollable or even difficult to be manipulated. Governmental regulations, technological advances, forces that shape marketplace competition are some examples of external forces (Armenakis and Bedeian, 1999). Hence, both institutional factors and contingency forces may be regarded as contextual forces that play a key role in the level of performance impact of management practices. Following the above discussion, we propose that performance impact of management practices is a function of (a) conformance to norms of acceptable practice (referred to as institutional factors – see DiMaggio and Powell, 1983; Carruthers and Espeland, 1995; Sila, 2007), and (b) the degree of fit between organizational structure and environmental uncertainty (referred to as contingency factors – see Melan, 1998; Ellis et al., 2002; Reed et al., 1996). Conversely, performance impact of management practices will be minimised where there is a perceived misfit for whatsoever reasons (see Donaldson, 2001). There has been a long-held belief that the major factor that distinguishes successful management practices and initiatives from the less successful or failed ones is the presence of dynamic, effective and supportive senior management (see Howe, 1977; Sethi, 1978; Haganaees and Hales, 1983; Tregoe et al., 1990; Riehl, 1988; Rodgers et al., 1993; Jones et al., 2000; Bennis and O’Tool, 2000; Drucker, 1985; Burnes, 2004). For example, previous research found that the lack of top management support poisoned efforts of organizations to manage strategically (Tregoe et al., 1990), undermined the effectiveness of quality management programmes (Shetty, 1986), and plagued the success of management-by-objectives (Sethi, 1978). In contrast, full-fledged support and commitment from the top are found to be critical to the success of computer-aided decision support systems (Neumann and Hadass, 1980), just-in-time materials planning programmes (Duncan, 1989), human resource management initiatives (Bohlander and Kinicki, 1988), and for a whole host of other breakthrough programmes (Witcher et al., 2008). Clearly, the findings highlight the need for managers (top, middle and first level management) not just to acquire appropriate skills and competences but also to adopt appropriate levels of orientation and commitment to managing practices and resolving the constraints under which the adopted practices are being managed and implemented. In the organizational behaviour literature, commitment has been conceptualised in two distinct ways (see Legge, 1995): one that refers to an individual’s psychological bond to an organization and as affective attachment and identification (Coopey and Hartley, 1991), while another regards it as the binding of the individual to behavioural acts (Becker, 1960; Kiesler, 1971; Salancik, 1977; Festinger, 1957). Whatever the approach to commitment and its related implications, 8 commitment has become a variable of interest because of the belief that an increase in commitment to practices leads, in some way, to an increase in organizational effectiveness. More specifically, Schein (1978, 1992) views commitment as a dimension of organizational effectiveness, and Steers (1977) sees it as a means of enhancing organizational effectiveness by improving people performance and reducing turnover. To achieve the desired performance impact of management practices, Salancik (1977) argues that commitment must be manifested not only in attitudes but also in actions and behaviours. A common denominator of these studies, as well as the extant literature on organizational commitment, is their emphasis on the paramount importance of employee commitment to the organization – an indication that unconditional management support and commitment to practices are taken for granted. Hence, there is still a need to extend these studies in understanding management (top, middle and first line management) commitment to organizational practices in particular and to organization generally. Although there is general consensus on the latter, scepticism about there being little or a lack of management commitment to organizational practices has been further reinforced by the high failure rate of management practices (e.g. Sethi, 1978; Riehl, 1988; Rodgers et al., 1993; Jones et al., 2000; Bennis and O’Tool, 2000; Burnes, 2004). Early analysis from more detailed case-study based research highlighted exemplary behaviours of supportive and committed management as: pursuing the process of adopting and implementing practices from planning to their successful execution, providing timely and continuous feedback (Locke and Latham, 1990) to other managerial levels; establishing continuous communications from the top down and from the bottom up, personal interest in lower level accomplishments and problems (Rodgers et al., 1993); possessing a developmental orientation to management programmes (i.e. focus on long-term growth of the firm, focus on the future) (Choi and Behling, 1997); and visible and active participation and involvement in managing and implementing practices (Leibowitz et al. 1985). In the absence of such behaviours, it is now widely recognised that many organizations are not capable of adapting effectively to changes in their environments with the consequence of the failure of their change management practices (see Choi and Behling, 1997). However, the explanation for the lack of such behaviours, and therefore of management commitment to practices, has so far remained unclear. Due to the existence of such barriers, this pessimistic conclusion is difficult to avoid. We argue that current trends in managing organizations in many large diversified sectors renders the ideals of the (change) management practices and initiatives unobtainable (e.g. ESRC, 2004; Burnes, 2004; Shaw and Whittington, 2003; Brindle, 1999; Lessem, 1998; Purcell, 1995; Rodgers and Hunter, 1991; Porter and Ketels, 2003; Mayer et al., 2003; Mellahi and Wilkinson, 2004). Such a gloomy picture of management commitment and support and strong evidence of descending into a culture of mis-(and ineffective) management of organizational practices also pose the question, what drives or otherwise these patterns of behaviour? 9 The debates on management failure to manage the adopted practices effectively or achieve the mission are stimulated by the contribution of Mellahi and Wilkinson (2004) who question the efficacy of the existing but dominant single, unilateral and one-sided perspectives to organizational failure. Based upon the two dominant deterministic and voluntaristic perspectives, they present a four-fold classification of organizational theories on the causes of organizational failure. Our concern in this paper in not to assess the efficacy of this integrative framework of determinants of organizational failure (simply because we agree that an either or approach – as opposed to both perspectives – to examining the failure phenomenon is futile and detrimental to a firm’s long-term growth and competitiveness) nor to explore the phenomenon of organizational failure. Rather, we revisit the dominant role of managers as the key decision makers and major determinants of organizational success/failure (voluntaristic perspective) and suggest a shift from purely being proactive to being more reactive to organizational issues and environmental conditions. Our suggestion here has a close affinity with, and can be explained by, and interpreted through, Simon’s (1946) rationality and bounded rationality theories as well as the work of contingency theorists, such as complex man vs. complex organization (Schein, 1965; Kast and Rosenzweig, 1973; Lawrence and Lorsch, 1969; Lorsch, 1973; Hall, 1972). In essence, we believe that existing conceptualisations of each of the two dominant deterministic and voluntaristic perspectives and further suggestions to merge the two perspectives have several limitations. First, much existing research on organizational failure views managerial perceptions and orientations as something which either make or break a firm (Bennis and O'Toole, 2000). So such an argument seems to undermine the underlying assumptions of the deterministic paradigm. Second, the paramount importance of management to the success or failure of the organization is refuted by Mellahi and Wilkinson’s finding that management actions do not yield an organizational failure per se. So this view appears to be in contradiction with the central premise of the voluntaristic perspective where managers’ mental models of the organizational issues and external environment are perceived to act as the major determinant of organizational success and failure. In the case of organizational failure, this contribution, however, does not tell us if management’s actions are perceived to be legitimate, rationale and fair by stakeholders. Third, a plethora of past research on management perceptions, orientations, and responses towards emerging forces and conditions tend to view management’s actions and responses as static and confined to a discrete time frame (see Isabella, 1990). This conventional approach, however, seems to disregard the dynamics of the organizational issues, the business environment, and the wider context in which a firm competes. Finally and fourth and as is theorised in this article, there is a shortage of studies of organizational failure with a focus on managerial perceptions and orientations and performance impact of management practices. Using insights from Simon’s (1957) bounded rationality theory, we now use factual examples relating to the 2008 global financial crisis to examine the interface between organizational and environmental issues, to reflect how (perfectly) rational decisions by managers are often not feasible in practice not least 10 because of the finite computational resources available for making them and existing and emerging environmental and organizational factors influencing them. Empirical Evidence: Dynamics of Management Practices While impediments to management practices and initiatives come in many forms, most authorities on modern management practices as enablers of organizational change attribute most of the blame to senior management (e.g. Isabella, 1990; Jones et al., 2000; Bennis and O’Tool, 2000; Abrahamson, 2000; Beer, 2003; Mayer et al. 2003; Shaw and Whittington, 2003; Beer and Nohria, 2000). However, to attribute most of the blame for failure of the adopted practices to management, irrespective of the potential impact of contextual inconsistencies on management’s orientations, seems to be rather unconvincing as it poses a serious challenge to the advocates of deterministic perspectives. Indeed, the impact of the 2008 global financial crisis was seen to be beyond management oversight and control. In the words of a Hedge fund boss: “… blaming us for credit crunch is like blaming passengers in a bus crash.” (Daily Mail, 2009). Of course the intention here is not to defend the decisions and actions taken by every manager simply because there is sufficient evidence of consciously taken decision and actions on the part of many managers which resulted in seriously underestimating and undermining the peculiarities of business environments ensued by their wider severe ramifications for the society and their stakeholders. In view of all societal, economical, and political ramifications of the 2007-2010 crisis period, a flurry of articles attempted to provide reasons for why, despite the heavy investment of all economic sectors in modern management practices to improve their viability, the worst financial crisis since the great depression of the 1930s has happened. A range of internal and external factors such as bankers’ and bank supervisors’ perception of risk, decline in bank capital, bank supervision over-reaction, regulatory burden, and cost of increased legal exposure have widely been cited as the key forces behind the credit crunch (Caprio et al., 2010). Clearly, these factors – referred to as ‘contextual forces’ in the literature as pertinent to organizational change management – are multifaceted. While some are temporary, secondary and peripheral in nature in terms of relative importance and will correct themselves over time, others are structural, primary, and core, and will not be eliminated with economic recovery. A robust and well-established argument into the global failure of business is that, in the words of the Britain’s former Chancellor, Alistair Darling, “the [management of] banks must take the blame for irresponsibility in the credit markets”. In a similar vein, US President Barack Obama has announced pay curbs for bank managers; in France, Nicolas Sarkozy has restricted traders’ rewards; and more recently, the former UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown believed that ‘the International 11 Monetary Fund would endorse a global bank levy by April’ to put the blame on the management of banks and financial institutions and partially heal and re-make the banking system. While pinning the blame for the crisis on ineffective bank managers and incompetent regulators may have seemed plausible enough during the turmoil of the past few years, we argue that unless the nature and importance of both internal and external contextual forces which attract or distract an individual manager from either supporting or abandoning a change practice and its wider organizational objectives are identified, managers will be unfairly and unnecessarily blamed for the collapse of some of the world’s most well known names such as Northern Rock, Royal Bank of Scotland, Woolworths, Lehman Brothers, and the Big Three Detroit's auto-giants (i.e. General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler). We argue that, depending on the nature and specific peculiarities of each contextual force and condition, managers adopt and apply different assumptions and orientations at different times in the process of managing practices. Contingent upon these factors, managers could not act completely rationally in their orientations and follow-up decisions and actions. Instead, these factors provide a ground for bounded and limited manager thought processes and their bounded computational ability, thereby pressing down upon the manager either to support a change practice and run the organization effectively or abandon it and fail to achieve its wider organizational objectives. Previous contextual research indicates that they have primarily focused on the collective responses taken by organizations in reacting to both internal and external environmental changes. Meyer et al.’s (1993) study of industry- and organizational-level changes taking place in hospitals from 1960 to 1980 revealed how changes in the contextual elements of differing competitive environments were necessary for successful organizational adaptation across time. Kelly and Amburgey’s (1991) study offers insights to complement those of Meyer et al. by concluding that, inter alia, environmental change does not necessarily increase the probability of strategic reorientation (see also Amburgey et al., 1993). Several other authors investigated the nature and impact of different contextual forces and concluded that in response to dramatic environmental changes, a shift in organizational structures and activities would increase short-term financial and long-term survival chances (Haveman, 1992), that organizations would resist pressures for change that are inconsistent with their identity and image (Fox-Wolfgramm et al., 1998), and that a successful change effort might depend more on the congruency or fit between content, contextual, and process considerations than the nature of an intended change (Damanpour, 1991). Others further adopted single industry and unique methodologies using mathematical techniques for modelling organizational responses to environmental pressures (see Gresov et al., 1993; Sastry, 1997). Walker et al. (2007) investigated the integrative influence of content, context, process, and individual differences on organizational change efforts. While these studies are notable for contributing to both theory and practice of organizational change and therefore enhancing our understanding of the impact of internal/external forces on an 12 organization’s effectiveness in responding to environmental changes, they have mainly been concerned with the nature of change programmes or collected data from employees – as opposed to how the contextual forces independently or indirectly through different managerial orientations impacted on the intended performance objectives of a change programme. In addition, most contextual studies have only investigated one of many contextual forces within a single case, thereby failing to strengthen the results by replicating the pattern-matching, thus increasing confidence in the robustness of the theory. Therefore, in creating a comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of contextual forces and organizational responses, these studies have often neglected different assumptions and orientations of managers, the extent of their rationality, and their resultants impact on the change practice performance. In consequence, the precise nature of these different and changing managerial orientations and support under different conditions and their impact on a change programme performance objectives, however, have yet to be fully explicated. Traditionally, researchers have viewed senior managers’ responses to emerging forces and conditions to be static or limited to a discrete time frame (Isabella, 1990). However, as Isabella succinctly put it, “as a change [management practice] unfolds, it demands continual adjustment and presents unending change for all concerned” (1990, p. 7). Although, researchers frequently observe that the idiosyncratic nature of senior managers’ orientations towards the adopted practices should make them a special area of interest in organizational change management research, the precise nature of their different orientations and support for different forces and conditions under which practices unfold have generally been poorly researched. Such lack of research has contributed to limited knowledge of the dynamics of senior management’s reactions towards different conditions and circumstances under which a practice or programme unfolds, thereby thwarting understanding of the complex set of contextual factors and conditions that contribute to senior management’s support or otherwise of practices or programmes. Although researchers have investigated a range of contextual forces and conditions in which an organization functions and therefore provided insights into the impact of internal and external factors on the efficacy of a (change) practice or programme, there is a notable dearth of research into the conditions under which managers decide to support or abandon a practice or initiative in their organization (see Van de Ven and Poole, 2005, for a review). This shortage of studies has meant little agreement on the relative impact of various contextual forces and conditions on management’s orientation towards adopted initiatives. Thus, what is considered to be a major force and determinant of management’s orientations towards a programme in one study may not even be considered in another. Such limitation has restricted understanding of the wide range of forces and conditions that may influence senior managers either to support or abandon a practice or programme (see Isabella, 1990; Tsoukas and Chia, 2002; Van de Ven and Poole, 2005). Given the aforementioned deficiencies in past research, there is a need to identify and elucidate the key 13 contextual forces and conditions that result in either management support of or abandoning a practice or initiative. Discussion: the Rationality of Behaviour In addition to the profound impact of either contextual forces or management support for and commitment to performance impact of practices (see Figure 1), and in an attempt to develop a more holistic view of the factors that influence the performance impact of management practices, we argue that such research should abandon an either/or approach and instead embed a dual approach to studying the performance impact of management practices. As Figure 2 shows, we propose that contextual forces and conditions play a part in shaping the nature and extent of management support and orientation ensued by influencing the performance objectives of management practices. In simple terms, the impact of contextual forces on management practices is viewed as something that is filtered through the attitudes and orientations that a manager has. Although each of the elements of the proposed unified model has its own theoretical underpinning, the integrated model in its totality provides the basis for utilising a different analytical approach from that of individual theories of deterministic and voluntaristic perspectives. On the one hand, the existing dominant theoretical approach to studying the failure and factors of management practices influencing their efficacy (see Figure 1) necessitates an imposed unilateral approach for organizational scholars to examine the impact of either contextual forces or management’s orientations on the performance impact of management practices. On the other hand, the synergy gained from integrating each of the two perspectives (see Figure 2) presents organizational scholars the choice of a vast array of competing possibilities to dish out the inefficacy of management practices and attribute it to the relevant sources. Hence, managers adopt and apply different assumptions and orientations at different times in the process of managing practices. [Insert figure 2 about here] Achieving a fair balance between the impediments to the efficacy of management practices in terms of contextual forces – i.e. environmental forces, organizational issues – and the adjusted management orientation would seem to require a subtle and multi-faceted theoretical approach which could serve the specific requirements of each of the three elements of the integrated model. Accordingly, a suggested theoretical perspective underpinning the proposed model is based on the stream of work referred to as “contextual issues”, “contingency theory” (Armenakis and Bedeian, 1999; Lawrence and Lorsch, 1967; Thompson, 1967; Woodward, 1958), “rational action theory” 14 (Dawes, 1988; Von Neumann and Morgenstern, 1944) and “bounded rationality” (Simon, 1990; Coleman, 1990). Such a multi-dimensional theoretical lens to formulate and construct the dynamics of contextual forces, management’s orientation, and the performance impact of management practices is needed both to compensate for the inadequacy of universalism in the conceptualisation and diffusion of many management practices, and more importantly to attune to a variety of environmental and organizational/internal influences and requirements. Contextual issues which are composed of both environmental forces and internal or organizational factors coalesce around the idea that the performance impact of management practices is largely subject to and indeed a function of the environment in which a firm operates as well as the internal organizational context in which the management practices are adopted and implemented (Mellahi and Wilkinson, 2004). So since organizations are deeply embedded in their external environments and embrace their own intra-firm procedures and processes, the performance impact of management practices depends on the extent to which the contextual forces influence management’s own orientation and attitude towards the adopted management practices. While contextual forces external to the organization are difficult to manage and beyond management control, contextual issues internal to the organization are rather easy to manage, can be manipulated by the management and indeed influence the way managers decide to go along or abandon practices. Depending on the nature of these external and internal contextual forces, the adopted management orientation towards the practices could be productive and counter-productive for both the efficacy of practices and the overall organizational performance. Attempts to handle the differing external and internal conditions faced by organizations and to improve the bottom-line impact of management practices effectively have resulted in the emergence of contingency theory ensued by a vast array of contingency models. For Kast and Rosenzweig (1973, p. ix), “the contingency view seeks to understand the interrelationships within and among subsystems as well as between the organization and its environment and to define patterns of relationships or configurations of variables … [and] emphasises the multivariate nature of organizations and attempts to understand how organizations operate under varying conditions and in specific circumstances”. It embraces a sensitivity to, a priority for, and a greater appreciation of, both intra- and interorganizational relationships. A predominant trend, observable in the extant research on utilising contingency theory has been the diverse nature of contextual –i.e. individual, organizational and environmental – variables that each study or model employs to reflect on different situational factors. Of these, for example, the appropriate levels of style of leadership (Fiedler, 1967; Osborn and Hunt, 1975), job design (Hulin and Blood, 1968; Kennedy and O’Neill, 1958; MacKinney et al., 1962; Turner and Lawrence, 1965), opportunities for participation in decision making (Alutto and Belasco, 1972; Conway, 1976; Singer, 1974; Vroom, 1960), and aspects of organizational structure (Burns and Stalker, 1961; Lawrence and Lorsch, 1965; Perrow, 1967; Pugh et al., 1969) were reported to vary 15 according to certain situational factors. Given the diversity and expanded influence of contextual and situational variables which are both within the remit of managers (organizational issues and individual characteristic) and also extended beyond their control (environmental forces), Shepard and Hougland (1978) unify and classify the existing contingency models into a few major integrated contingency theories. Based upon a bundle of variables believed to mediate between strategies (e.g. leadership, job design) and outcomes (e.g. satisfaction, productivity), they label their first approach as ‘complex man’ and call a second contingency approach as ‘complex organization’ (see Indik, 1968). Of these, the focus of the former is on individual differences and the emphasis of the later is on organizational and environmental forces. Since we have postulated that management’s orientation and attitude towards the adopted practices will change in accordance with the environmental and organizational pressures and experiences, both contingency theories of complex man and complex organization help enhance the understanding of management’s reaction and decisions to the existing forces. The question remains: to what extent are such management’s reactions and decisions in response to contextual forces deemed rationale (to both themselves and to others)? To illustrate this point and explore further the degree of rationality or otherwise of managers’ behavioural models for contextual forces decision-making, we gain insights from “rational action (choice) theory” (Dawes, 1988; Von Neumann and Morgenstern, 1944) and “bounded rationality theory” (Simon, 1990; Coleman, 1990). Rational action theory postulates that an individual (a manager) acts as if balancing costs against benefits to arrive at an action that maximises personal advantages. Thus, managers choose the best action according to unchanging and stable preference functions and constraints facing them (Friedman, 1953). Accordingly, patterns of behaviours in organizations reflect the choices made by managers as they try to maximise their benefits and minimise their costs. Managers make decisions and take actions about how to cope with rather predictable organizational issues and environmental uncertainty facing the organization by adopting a rational process where they compare the costs and benefits of certain actions based on their own preferences. This theory therefore postulates an ‘economic man’ who, in the course of being ‘economic’, is also rational. This man has impressively relevant, clear, and voluminous knowledge about various aspects of the environment (Simon, 1955). This wealth of literature allows us to distinguish between two types of underlying assumptions of rational action theory: core assumptions versus peripheral assumptions. The core assumptions of rational action theory are composed of: preference proposition, constraints proposition, and utility maximisation proposition. Peripheral or supplementary assumptions, on the other hand, are specifications of the core assumptions: they indicate that what kind of preferences or constraints are to be used in applications of the rational action theory. The question remains as whether individuals always act rationally. Rational action theory does not assume that actors always choose to behave ‘rationally’ or that choices are ‘right’. But we assume that people always act rationally. Managers as rational actors 16 or value-maximising make choices in such a way to maximise outcomes. They choose emotionally or from inadequate information. They may mistakenly calculate the outcome of a situation. Rationality of their decision making is therefore restricted by the information they have, the cognitive limitations of their minds, and the finite amount of time they have to make decisions (Simon, 1957; Williamson, 1981; Gigerenzer and Selten, 2002; Kahneman, 2003). To accommodate such restrictions to the extent of rationality of organizational actors, Simon (1990; 1991) coined the term ‘bounded rationality’ as an alternative basis for the mathematical modelling of decision making to argue that the decision maker is a satisfier who seeks satisfactory solutions rather than an optimal one. Another way of looking at bounded rationality is that because decision makers lack the ability and resources to arrive at the optimal solution, they instead apply their rationality only after having greatly simplified the choices available. But managers cannot always act according to their preferences. The concept of bounded rationality revises this assumption to account for the fact that perfectly rational decisions are often not feasible in practice due to the finite computational resources available for making them. Due to the complexity of the situation, their inability to process and compute the expected utility of every alternative action (coupled with tendency to be more realistic), economic agents employ the use of heuristics to make decisions and judgements rather than a strict rigid rule of optimisation. In Simon’s words, boundedly rational agents experience limits in formulating and solving complex problems and in processing (receiving, string, retrieving, transmitting) information (cited by Williamson, 1981). Four cases from an early banking investigation (ESRC, 2004) indicated that senior managers were keen to take a fresh and critical look at the whole range of change initiatives in order to improve quality and productivity and helping themselves out to improve quality and productivity to boost commitment to make them successful. However it identified scepticism attached to the extent to which top executives devote their time to support various organizational changes. Similarly, from the 2008 global financial crisis, the Financial Times columnist, Stefan Stern, expressed the turning away from good management, citing Alfred Chandler, that modern capitalism had been achieved through “the long-term stability and growth of their enterprises to those that maximised short-term profits” (Stern, 2008), but this was no longer the case. Stern omitted Chandler’s (1977) next sentence, “the continuing existence of their enterprises was essential to their lifetime careers”, asserting that banks were “always chasing the next deal, too many businesses neglect the boring but crucial issue of management”, and therefore, like rats that love their bait, managers pursued seemingly ‘boundedly rational’ decisions, through involvement in the subprime markets for short-term gains and personal bonuses (economic man), that were not necessarily most optimal, only eventually to be caught out. Tom Stewart (former editor of Harvard Business Review) commented, “it is no accident that Goldman Sachs … has survived [the 2008] crisis best … I bet that each of the players and victims in this credit crisis began to smell the rot in their mortgage-derivatives books at about the same time, within weeks, 17 even days of each other” (see McKillop, 2009). Like for rats, “greed is bad, and stupidity is bad, but bad management is worst of all” (ibid; see also Witcher and Chau, 2010)! Conclusion This article has explored how organizations and leaders during the 2008 global financial crisis behaved and made strategic decisions were rational in the context of our synthesis of the literature on the nature, scope and impact of management practices. We have discussed two separate and disconnected theoretical perspectives underpinning the failure of management practices: deterministic (contextual forces) versus voluntaristic (management’s orientations), and proposed a unified model and several associated underpinning theoretical perspectives. The central premise and contribution of the proposed model is that instead of regarding the issue of contextual forces and management influences and orientations as an either/or phenomenon, it views contextual influence as something that is filtered and mediated through the attitudes and orientations which a manager has. (Boundedly) rational theory suggests that the decisions made by leaders during the 2008 financial crisis were indeed rational, but not optimal. Acknowledgment: This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council grant (grant number: RES000-22-4227). 18 REFERENCES Abrahamson, E. (2000). ‘Change without pain’, Harvard Business Review, 78 (July-August), pp. 75-79. Agarwal, R., R. Echambadi, and M. B. Sarkar (2002). ‘The conditioning effect of time on firm survival: a life cycle approach’, Academy of Management Journal, 45, pp. 971994. Ahire, S.L., D. Y. Golhar and M. A. Waller (1996). ‘Development and validation of TQM implementation constructs’, Decision Sciences, 27, pp. 23–56. Alutto, J. A. and J. A. Belasco (1972), ‘A typology for participation in organizational decision making’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, pp. 117-125. Amburgey T. L., D. Kelly and W. P. Barnett (1993). ‘Resetting the clock: the dynamics of organizational failure’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, pp. 51-73. Anderson, P. and M. Tushman (2001). ‘Organizational environments and industry exit: the effects of uncertainty, munificence and complexity’, Industrial and Corporate Change, 10, pp. 675 711. Armenakis, A. A. and A. G. Bedeian (1999). ‘Organizational change: A review of theory and research in the 1990s’, Journal of Management, 25(3), pp. 293-315. Atkinson, P. E. (1990). Creating culture change: The key to successful total quality management. IFS Publications, Bedford. Audit Commission (2001). 2000/2001 Local authority performance indicators in England and Wales. HMSO, London. Becker, H. S. (1960). ‘Notes on the concept of commitment’, American Journal of Sociology, 66, pp. 32-44. Beer, M. (2003). ‘Why total quality management programs do not persist: The role of management quality and implications for leading a TQM transformation’, Decision Sciences, 34(4), pp. 623-642. Beer, M. and N. Nohria (2000). ‘Cracking the code of change’, Harvard Business Review, 78 (May-June), pp. 133-141. Bennis, W. and J. O’Toole (2000). ‘Don’t hire the wrong CEO’, Harvard Business Review, 78 (May-June), pp. 171-177. Benson, G., J. Saraph, and R. Schroeder (1991). ‘The effects of organizational context on quality management: an empirical investigation’, Management Science, 37(9), pp. 1107–1124. Bohlander, G. W. and A. J. Kinicki (1988). ‘Where personnel and productivity meet’, Personnel Administrator, 33(9), pp.122-130. Boje, D. M. and R. D. Winsor (1993). ‘The resurrection of Taylorism: Total quality management's hidden agenda’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 6(4), pp. 57–70. Brindle, D. (1999). ‘Pensions computer upgrade hit by 1,900 bugs as deadline looms’, The Guardian, pp.3. Brown, A. D. and K. Starkey (2000). ‘Organizational identity and organizational learning: a psychodynamic perspective’, Academy of Management Review, 25, pp.102–120. Burnes, B. (2004). Managing Change (4th edn). FT Prentice Hall, Essex. Burns, T. and C. M. Stalker (1961), The Management of Innovation, London: Tavistock, 1961. Caprio Jr., G., Demirgüç-Kunt, A. and Kane, E J. (2010). ‘The 2007 Meltdown in Structured Securitization: Searching for Lessons, not Scapegoats. World Bank Research Observer, 25(1), pp. 125-155. Carruthers B. G. and W. W. Espeland (1995). ‘Accounting, ambiguity, and the new institutionalism’, Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(4), pp. 313–328. 19 Chandler, A. (1977). The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, London: Belknapp. Chau, V. S. and B. J. Witcher (2005). ‘Longitudinal Tracer Studies: Research Methodology of the Middle Range’, British Journal of Management, 16(4), pp. 343-355. Choi, T. and O. Behling (1997). ‘Top managers and tqm success: one more look after all these years’, Academy of Management Executive, 11(1), pp. 37-47. CIPD (2006). Graduates in the Workplace: Does a Degree Add Value?, Chartered Institute of Personal Development, London, . Coleman, J. (1990). Foundations of Social Theory. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Conway, J. A. (1976), ‘Test of linearity between teachers participation in decision making and their perceptions of their schools as organizations’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 21, pp. 130-139. Coopey, J. and J. Hartley (1991). `Reconsidering the Case for Organizational Commitment', Human Resource Management Journal, 1(3), pp. 18-32. Coulson-Thomas, C. and T. Coe (1991). The Flat Organization: Philosophy and Practice. BIM, Corby. Currie, G. (1999). ‘The influence of middle managers in the business planning process: a case study in the UK NHS’, British Journal of Management, 10, pp. 141–155. Daily Mail (2009). ‘Hedge fund boss: “blaming us for credit crunch is like blaming passengers in a bus crash”’, Daily Mail Online, 28th January 2009. Damanpour, F. (1991). ‘Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators’, Academy of Management Journal, 34, pp. 555–590. Dawes, R. (1988). Rational Choice in an Uncertain World. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: New York. Dean, J. and D. Bowen (1994). ‘Managing theory and total quality: improving research and practice through theory development’, Academy of Management Review, 19 (3), pp. 392–418. Dess, G. G. and D. W. Beard (1984). ‘Dimensions of organizational task environments’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, pp. 52 73. DiMaggio, P. J. and W. W. Powell (1983). ‘The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields’, American Sociological Review, 48, pp. 147-160. Donaldson, L. (2001). The Contingency Theory of Organizations. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. Dow, D., D. Samson, and S. Ford (1999). ‘Exploding the myth: do all quality management practices contribute to superior quality performance?’, Production and Operations Management, 8, pp. 1–27. Drucker, P. F. (1985). Innovation and Entrepreneurship. HarperBusiness, New York, NY. Duncan, R. B. (1972). ‘Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, pp. 313-327. Duncan, W .L. (1989). ‘The calm before the storm’, Production & Inventory Management Review with APICS News, 9, pp. 54-55. Ellis, S., T. Almor, and O. Shenkar (2002). ‘Structural contingency revisited: toward a dynamic system model’, Emergence, 4(4), pp. 51–85. ESRC (2004). Mapping the Public Policy Landscape. The UK Productivity Gap: What Research Tells Us and What We Need to Find Out. Economic and Social Research Council Seminar Series, http://www.esrc. ac.uk/ESRCContent/DownloadDocs/UK_Productivity.pdf. Ezzamel, M., S. Lilley, and H. Willmott (1994), ‘The ‘new organization’ and the ‘new managerial work’’, European Management Journal, 12(4), pp.454-461. 20 Festinger, L. A. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA. Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A Theory of Leadership Effectiveness, New York: McGraw-Hill. Fox-Wolfgramm, S., K. Boal, and Hunt, J. (1998). ‘Organizational adaptation to institutional change: A comparative study of first-order change in prospector and defender banks’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, pp. 87–126. Friedman, M. (1953). The Methodology of Positive Economics: Essays in Positive Economics. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Ghobadian, A. and D. Gallear (1996). ‘Total Quality Management in SMEs’, OMEGA International Journal of Management Science, 24(1), pp. 83-106. Gigerenzer G. and R. Selten (eds.) (2002). Bounded Rationality: The Adaptive Toolbox. The MIT Press, Cambridge. Glover, L. and M. Noon (2005). ‘Shop-floor workers’ response to quality management initiatives: broadening the disciplined worker thesis’, Work, Employment and Society, 19(4), pp. 727-745. Gresov, C., H. Haveman, and T. Oliva (1993). ‘Organizational design, inertia, and the dynamics of competitive response’, Organization Science, 4, pp. 181–208. Guardian Newspaper (2008), ‘Justin McCurry in Tokyo’, guardian.co.uk, Thursday 6 November 2008 16.11 GMT. Hackman, J. R. and R. Wageman (1995). ‘Total Quality Management: Empirical, Conceptual, and Practical Issues’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(June), pp. 309–342. Haganaees, K. and L. Hales (1983). ‘Scandinavian models of employee participation’, Advanced Management Journal, 48(1), pp.21-30. Hall, R. H. (1972). Organizations: Structure and Process. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J. Hambrick, D. and P. Mason (1984). ‘Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of its Top Managers’, Academy of Management Journal, 15(3), pp. 514-535. Hannan, M. T. and J. H. Freeman (1977). ‘The population ecology of organizations’, American Journal of Sociology, 83, pp. 929 984. Harrington, H. J. (1997). ‘The fallacy of universal best practices’, The TQM Magazine, 9 (1), pp. 61 – 75. Haveman, H. (1992). ‘Between a rock and a hard place: Organizational change and performance under conditions of fundamental environmental transformation’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 37, pp. 48–75. Hayes, R. and S. Wheelwright (1984). Restoring our Competitive Edge: Competing Through Manufacturing. Wiley, New York. Homburg C. Jr., J. P. Workman, and H. Krohmer (1999). ‘Marketing's influence within the firm’, Journal of Marketing, 63(2), pp. 1-17. Howe, R. J. (1977). ‘Building teams for increased productivity’, Personnel Journal, 56(1), pp.16-22. Hulin, C. L. and M. R. Blood (1968). ‘Job enlargement, individual differences, and worker responses’, Psychological Bulletin, 69, pp. 41-55. Indik, B. P. (1968). ‘The scope of the problem and some suggestions toward a solution’, in B. P. Indik and F. K. Berrien (Eds,), People, Groups, and Organizations, New York: Teachers College Press, pp, 326-29. IPM (1993), Quality: People Management Matters. IPM Research Series, Short Run Press Ltd, Exeter, UK. Isabella, L. (1990). ‘Evolving interpretations as a change unfolds: How managers construe key organizational events’, Academy of Management Journal, 33, pp. 7–41. 21 Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink. Houghton Mifflin, Boston. Jones, G. R., G. M. George, and C. W. L. Hill (2000). Contemporary Management (2nd edn.). McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA, USA. Kahneman, D. (2003). ‘A psychological perspective on economics’, American Economic Review, 93, pp. 162–168. Kast, F. E. and J. E. Rosenzweig (1973). Contingency views of organization and management. Science Research Associates, Chicago, III. Kelly, D. and T. L. Amburgey (1991). ‘Organizational inertia and momentum: A dynamic model of strategic change’, Academy of Management Journal, 34, pp. 591-612. Kennedy, J. E. and H. E. O'Neill (1958), ‘Job content and workers’ opinions’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 42, pp. 372-375. Kiesler, C. A. (Ed.) (1971). The psychology of commitment: Experiments linking behavior to belief. Academic Press, New York. Kotter, J. P. (1996). Leading Change. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. Lawrence, P. R. and J. W. Lorsch (1969). Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration. Irwin, Homewood, IL. Lawrence, P. W. and J. W. Lorsch (1967). Organization and Environment. Harvard University Press, Boston, MA. Legge, K. (1995). Human Resource Management. Macmillan, Houndsmills, Basingstoke. Leibowitz, Z. B.; Farren, C.; and Kaye, B. (1985). ‘The 12-Fold Path to CD Enlightenment’. Training and Development Journal, 35 (7), pp. 72-79. Lessem, R. (1998). Management Development through Cultural Diversity. Routledge, London. Locke, E. A. and G. P. Latham (1990). A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Lorsch, J. W. (1973). ‘Environment, Organization and the Individual’. In A. R. Negandhi (ed.), Modern Organizational Theory, p. 132-144. Kent State University Press, Kent, OH. Maani, K. (1989). ‘Productivity and profitability through quality — myth and reality’, International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 11(7), pp. 19–37. MacKinney, A. C., P. F. Wernimont and W. O. Galitz (1962), ‘Has specialization reduced job satisfaction?’, Personnel, 39(1), pp. 8-17. Mayer, J., P. Salovey, and D. Caruso (2003). ‘Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0’, Emotion, 3(1), pp. 97-105. McCabe, D. (1999). ‘TQM: Anti-Union Trojan Horse or Management’s Albatross?’ Work, Employment and Society, 13(4),pp. 665-691. McKillop, T. (2009). House of Commons Minutes of Evidence, Treasury Committee, Banking Crisis, 10th February. Melan, H. E. (1998). ‘Implementing TQM: a contingency approach to intervention and change’, International Journal of Quality Science, 3(2), pp. 126–146. Mellahi, K. and A. Wilkinson (2004). ‘Organizational Failure: a critique of recent research and a proposed integrative framework’, International Journal of Management Reviews, 5/6 (2), pp. 21-41. Mellahi, K., P. Jackson, and L. Sparks (2002). ‘An exploratory study into failure in successful organizations: the case of Marks and Spencer’, British Journal of Management, 13(1), pp. 15–30. Miller, D. (1990). The Icarus Paradox - How Exceptional Companies bring about their own Downfall: New Lessons in the Dynamics of Corporate Success, Decline, and Renewal. Harper Business, New York. 22 Miller, K. D. 1992. ‘A framework for integrated risk management in international business’, Journal of International Business Studies, 23, pp. 311-331. Neumann, S. and M. Hadass (1980). ‘DSS and strategic decisions’, California Management Review, 22(2), pp. 77-84. ODPM (OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER) (2001). Towns and Cities: Partners in Urban Renaissance: Breaking down the Barriers. ODPM/CABE, London. Osborn, R. N. and J. G. Hunt (1975), ‘An adaptive-reactive theory of leadership: the role of macro variables in leadership research’, Organization and Administrative Sciences, 6, pp. 27-44. Perrow, C. (1967). ‘A framework for the comparative analysis of organizations’, American Sociological Review, 32, pp. 194-208. Porter, M. E. and C. Ketels (2003). ‘UK Competitiveness: Moving to the Next Stage’, DTI Economics Paper No.3. Department of Industry and Trade & Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), London. Powell, T. C. (1995). ‘Total quality management as competitive advantage: a review and empirical study’, Strategic Management Journal, 16, pp. 15–37. Pugh, D. S., D. J. Hickson and C. R. Hinings (1969). ‘An empirical taxonomy of structures of work organizations’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 14, pp.115-126. Purcell, J. (1995). ‘The impact of corporate strategy on human resource management’, In J. Storey (Ed.), New Perspectives on Human Resource Management, p. 67-91. Routledge, London. Reavill, L. R. P. (1999). ‘What is the future direction of TQM development’, The TQM Magazine, 11(5), pp. 291–298. Reed, R., D. Lemak and J. Montgomery (1996). ‘Beyond process: TQM content and firm performance’, Academy of Management Review, 21(1), pp. 173–202. Riehl, J. R. (1988). ‘Planning for Total Quality: The information technology component’, SAM Advanced Management Journal, 53(4), pp. 13-19. Rodgers, R. and J. E. Hunter (1991). ‘Impact of Management By Objectives on Organizational Productivity’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, pp. 322–336. Rodgers, R., Hunter, J.E., and D. L. Rogers (1993). ‘Influence of top management commitment on management program success’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), pp.151-155. Salancik, G. R. (1977). ‘Commitment and the control of organizational behavior and belief’. In B. Staw and G. R. Salancik (Eds.), New Directions in Organizational Behaviour, p. 1-54. St. Clair Press, Chicago, IL. Samson, D. and M. Terziovski (1999). ‘The relationship between total quality management practices and operational performance’, Journal of Operations Management, 17(4), pp. 393–409. Sastry, M. (1997). ‘Problems and paradoxes in a model of punctuated organizational change’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, pp. 237–275. Schein, E. H. (1965). Organizational Psychology. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Schein, E. H. (1992). ‘Career anchors and job/role planning: The links between career planning and career development’. In D. H. Montross and C.J. Shinkman (Eds.), Career Development: Theory and Practice. Thomas, Springfield. Schein, E.H. (1978). Career Dynamics: Matching Individual and Organizational Needs. Addison-Wesley, Reading. Schonberger, R. (1986). World Class Manufacturing. Free Press, New York. Sethi, N.K. (1978). ‘Collaborative MBO’, Industrial Management, 20(5), pp.1-4. Shaw, D. and R. Whittington (2003). ‘The art of change in the public sector’, European Business Forum (EBF), 14: Summer. 23 Shepard, J. M. and J. G. Jr. Hougland (1978). ‘Contingency theory: complex man or complex organization’, Academy of Management Review, 3(3), pp. 413-427. Shetty, Y. K. (1986). ‘Quality, productivity and profit performance: learning from research and practice’, National Productivity Review, 5(2), pp.166-173. Siebers, P., U. Aickelin, G. Battisti, H. Celia, A. Iona, C. Clegg, A. Petrescu, X. Fu, R. De Hoyos (2008), ‘Enhancing productivity; the role of management practices’, Advanced Institute of Management, London, Working Paper No. 065, p. 5-6. Sila, I. (2007). ‘Examining the effects of contextual factors on TQM and performance through the lens of organizational theories: An empirical study’, Journal of Operations Management, 25(1), pp. 83–109. Silvestro, R. (2001). ‘Towards a contingency theory of TQM in services: How implementation varies on the basis of volume and variety’, International Journal of Quality and Reliability Management, 18(3), pp. 254–288. Simon, H. A. (1946). Administrative Behaviour. Macmillan, New York. Simon, H. A. (1955). ‘A behavioral model of rational choice’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, February, pp. 99-118. Simon, H. A. (1957). Administrative Behaviour. Free Press, New York. Simon, H. A. (1990). ‘Invariants of human behavior’, Annual Review of Psychology, 41, pp. 1–19. Simon, H. A. (1991). ‘Cognitive architectures and rational analysis: Comment’. In K. Vanlehn (Ed.), Architectures for Intelligence, p. 25–39. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. Singer, J. N. (1974), ‘Participative decision-making about work: an overdue look at variables which mediate its effects’, Sociology of Work and Occupations, 1, pp. 347-371. Sitkin, S.B., K.M. Sutcliffe, and R.G. Schroeder (1994). ‘Distinguishing control from learning in Total Quality Management: A contingency perspective’, Academy of Management Review, 19(3), pp. 537–564. Sorge, A. and A. V. Witteloostuijn (2004). `The (non)sense of organizational change: An essay about universal management hypes, sick consultancy metaphors, and healthy organization theories', Organization Studies, 24, pp. 1205-1231. Sousa R. and C. Voss (2001). ‘Quality management: universal or context-dependent?’, Production and Operations Management Journal, 10(4), pp. 383–404. Staw, B. M., L. E. Sandelands, and J. E. Dutton (1981). ‘Threat-rigidity effects in organizational behavior: a multilevel analysis’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, pp. 501-524. Steers, R. M. (1977). ‘Antecedents and outcomes of organizational commitment’, Administrative Science Quarterly, 22, pp. 46-56. Stern, S. (2008). ‘White House needs a competent manager’, Financial Times, 4th February. Stickland, F. (1998). The Dynamics of Change: Insights into Organizational Transition from the Natural World. Routledge, London. Storey, J. (1992). Developments in the Management of Human Resources. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford. Thompson, J. (1967). Organizations in Action. McGraw-Hill, New York. Tregoe, B. B., J. W. Zimmerman, R. A. Smith, and P. M. Tobia (1990), ‘Implementing the vision; the lessons learned’, Planning Review, 18(1), pp.39-44. Tsoukas, H. and R. Chia (2002). ‘On organizational becoming: Rethinking organizational change’, Organization Science, 13(5), pp. 567–582. Turner, A. N. and P. R. Lawrence (1965), Industrial Jobs and the Worker: An Investigation of Responses to Task Attributes, Division of Research, Graduate School of Business Administration, Harvard University: Boston. 24 Van de Van, A. H. and M. S. Poole (2005). ‘Alternative approaches for studying organizational change’, Organization Studies, 26(9), pp. 1377-1404. Von Neumann, J. and O. Morgenstern (1944). Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. Voss, C. A. (1995). ‘Alternative paradigms for manufacturing strategy’, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 15(4), pp. 5-16. Vroom, V. H. (1960), Some Personality Determinants of the Effects of Participation, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Wagner, C., P. P. Groenewegen, D.H. de Bakker and G. van der Wal (2001). ‘Environmental and organizational determinants of quality management’, Quality Management in Health Care, 9(4), pp. 63–76. Walker, H. J., A. A. Armenakis and. J. B. Bernerth (2007). ‘Factors influencing organizational change efforts: An integrative investigation of change content, context, process and individual differences’, Journal of Organizational Change Management, 20(6), pp. 761-773. Wall T.D. and S. J. Wood (2005). ‘The romance of human resource management and business performance and the case for big science’, Human Relations, 58, pp. 1–34. Wilkinson, A., T. Redman, E. Snape and M. Marchington (1998). Managing with Total Quality Management: Theory and Practice. Macmillan, London. Williamson, O. (1981). ‘The economies of organization: the transaction cost approach’. American Journal of Sociology, 87(2), pp. 548-577. Witcher, B. J. and V. S. Chau (2010). ‘The global financial crisis: a question of leadership’, in Strategic Management: Principles and Practice, South-Western Cengage Learning, Andover, pp. 313-315. Witcher, B. J., V. S. Chau and P. Harding (2008). ‘Dynamic capabilities: top executive audits and hoshin kanri at Nissan South Africa’, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 28(6), pp. 540-61. Woodward, J. (1958). Management and Technology. H.M.S.O., London. Worrall, L. and C. L. Cooper (1998). Quality of Working life 1998 Survey of Managers’ Changing experiences. Institute of Management, London. 25 Figures (1.a) (1.b) Management’s orientation Contextual forces Performance impact of management practices Figure 1. Factors influencing Performance impact of management practices Management’s orientations and support Contextual factors Performance impact of Management practices Figure 2. The interplay of contextual forces, management’s orientation, and performance impact of management practices 26