Peak Load Pricing and price discimination.

advertisement

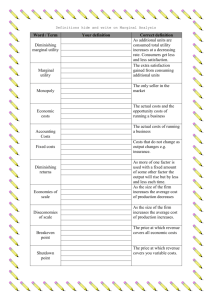

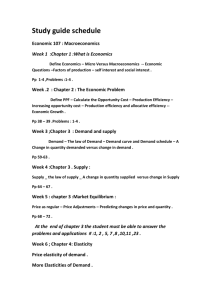

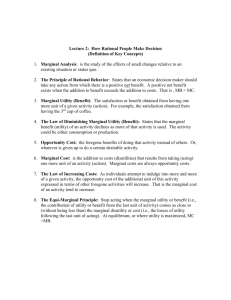

CHAPTER 13. PRICING PRACTICES ...................................................................................... 1 SECTION 1. MARKET EQUILIBRIUM, SHORTAGES AND SURPLUSES ......................... 1 EXAMPLES: Price Controls in Different Kinds of Markets ......................................... 4 SECTION 4. RETURN ON INVESTMENT ............................................................................... 6 A. The Permitted Rate of Return ........................................................................................... 6 B. The Rate Base ...................................................................................................................... 6 SECTION 5. PRICE DISCRIMINATION AND PEAK LOAD PRICING ................................. 8 A. Peak Load Pricing ............................................................................................................... 9 B. Price Discrimination............................................................................................................ 9 1. Third Degree Price Discrimination .................................................................................... 9 2. Second degree price discrimination ................................................................................. 12 3. First Degree Price Discrimination.................................................................................... 14 SECTION 6. MULTIPLE PRODUCT PRICING ..................................................................... 15 2. Tied Products ................................................................................................................... 15 EXAMPLE: Tying Home Health Care to Hospital Services ......................................... 16 SECTION 7. CONCLUSION................................................................................................. 16 CHAPTER 13. PRICING PRACTICES The U.S. government continually rediscovers the variety and complexity of management techniques when it attempts to control managerial discretion. In this chapter, we will focus on the last large scale U.S. government attempt to control pricing in which the government learned the hard way about different pricing techniques. From this exercise it will be possible to review various pricing techniques and how managers optimize when using several instruments simultaneously. Most importantly, it will be apparent that rigid pricing rules do not work well for government or for firms. SECTION 1. MARKET EQUILIBRIUM, SHORTAGES AND SURPLUSES In markets where money is used, buyers and sellers provide the detailed information with which to establish prices for the goods that are traded. This information is extremely detailed and applies to the moment at which trade occurs. Hours later a new set of circumstances involves a new set of information and prices can dramatically change. That’s the reason that people sit at their computer terminals all day or stand in the pit at futures markets or hang by the telephone waiting for deals; circumstances are always changing. These people are waiting for information about the supply and demand conditions that affect the price each moment and they can make a lot of money simply by taking advantage of the changes in prices due to the moment-to-moment changes in information about supply and demand. The demand is what buyers are willing and able to buy at different prices during a given period, ceteris paribus (holding other factors constant). This demand is affected by certain "demand determinants" (see chapter 5). On the other hand, supply indicates what sellers are willing and able to provide at different prices during a given time period, ceteris paribus. The supply is affected by supply determinants. These are the same influences that would affect a firm’s marginal cost curve (see chapter 8). The quantity supplied is sensitive to price, just as the quantity demanded is. While the demand curve shows the quantity demanded becomes larger at lower prices, the supply curve shows that the quantity supplied becomes lower at lower prices. Where the supply and demand curves cross is the equilibrium. Figure 1-1 shows such an equilibrium. However, when decision making is centralized either by giving pricing authority to the government or by giving price authority to higher levels of management within a firm, there is likely to be a loss of capability to process and use the information necessary to make good pricing decisions. Rather than choosing a price that will be acceptable to buyers or sellers, a price may be picked that does not “clear the market.” Clearing the market means that the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied of a good or service are equal to each other. The economic term for such market clearing is equilibrium. If centralized pricing decisions lead to a price that is below this equilibrium, then a shortage results because buyers will want to buy more than they would at the higher equilibrium price while sellers will want to supply less than they would at the equilibrium price. At any given price a shortage is the difference between the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied as shown in Figure 1-1. Such shortages are not just caused by government. The scalping that occurs outside many private events reflects the difficulty of the private suppliers of these events to know all of the conditions that affect their customers’ willingness and ability to buy tickets. Scalping is the self-organizing (and often illegal) activity that arises to eliminate a shortage. Sometimes, shortages are simply a marketing ploy to call attention to a product, as in the Cabbage patch doll craze. But it is not just shortages that can be created by centralized decision making. If prices are set above an equilibrium price, then there will be a surplus because buyers will want to buy less than they would at the lower equilibrium price while sellers will want to supply more than they would at the lower equilibrium price. At any given price a surplus is the difference between the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded as shown in Figure 1-1. Figure 13-1. Equilibrium and Supply and Demand Price Supply SURPLUS Price Floor Price Ceiling Demand SHORTAGE Quantity NOTE: The equilibrium price in a market occurs where the supply and demand curves intersect. If prices are below the equilibrium level, then a shortage exists. If prices are too high then a surplus would occur. Whenever a market is in disequilibrium there are natural market forces that will tend to push prices back to the equilibrium level. When there are surpluses there are queues of sellers (or their capacity to provide service) standing around or queues of goods or services that are sitting in inventory or on the books. Such surpluses often result from price floors (constraints on how low prices can be set). When there are shortages there are queues of buyers, and such shortages often result from price ceilings (constraints on how high prices can be set). Both queues of people and queues of goods, services, and capacity are expensive, and the people experience those expenses will gladly make a cut rate deal to lower those costs- even illegally. In traveling around the world, we often confronts situations in which people are adapting to disequilibria. By watching what is happening we can identify what market is in disequilibrium by the kinds of activities that people are engaged in. When surpluses occur, the sellers are experiencing high costs of holding the goods in inventory , holding onto people who aren’t working, and holding excess capacity to serve customers. The sellers will begin running sales, provide discounts, and lower prices in any number of creative ways. If the price falls too far they may simply throw the excess item out and write it off as a total loss. There may even be an illegal attempt to find a way to get insurance companies to pay for the loss. Ultimately, surpluses lead to the exit of firms in the market place. When shortages occur, the buyers cannot get what they want and they intensely look for people who have the scarce item and bid the price of the item upward. If prices cannot be bid upward, businesses or government must find a way to ration the scarce item. Such rationing includes schemes like “first come first served,” lotteries, or rationing coupons. Inevitably people begin to search widely for alternative sources of a commodity and to trade amongst each other. If such trade is legal then it is called a white market. If such trading is illegal then the market is called a black market. Unfortunately, in either type of market the seller does not get the benefit of the higher price and therefore does nothing to eliminate the shortage. In this chapter several American experiences with price controls are examined to see what happens- or doesn’t happen in markets where centralized control occur. The last nationwide price control program occurred in the 1970s. However, there have been various kinds of price controls in specific sectors including public utilities, health care, energy, rental properties, wage rates, interest rates, and exchange rates. These types of controls have been frequent and pervasive enough that a great deal can be learned from them about the difficulty of centralized decision making- whether from the public sector or the private sector. EXAMPLES: Price Controls in Different Kinds of Markets Following are some situations that appeared due to price controls that will test your ability to detect what kind of queues are occurring, what type of price control (ceilings or floors) is involved, whether there is a shortage or a surplus of the different items in question, and what kind of market distortions result from the control: 1. 2. 3. Minimum wage. The minimum wage is only sporadically reset by congress to reflect inflation. When it is reset, often the changes in wages are very large. Small businesses and farms may suddenly find they cannot afford to hire workers at the higher wage rate. ANSWER: The market is the labor market and in this market, labor is the seller. Since sellers are waiting around for jobs, the minimum wage is a price floor and has resulted in a surplus of labor. So many people misclassify such a situation as a “shortage of jobs” which would result in an incorrect analysis of the supply and demand conditions in the labor market. An important side effect would be the use of illegal immigrants in place of American labor. Oil Price Controls. In 1973-74 there were price controls on oil in the United States. Long lines of people could be seen at the service stations, waiting for a chance to fill up their cars. Occasionally people would pay to take someone else’s place at the gas pump. ANSWER: The market is the market for gasoline. It is the buyers who are standing in line, and therefore the government is imposing a price ceiling. The rationing scheme that is being used is a first-come-first-served white market in gasoline queues. One of the side effects of long lines was irritability and even acts of violence against service station owners Exchange Rate for the Dollar. After World War II, a fixed exchange rate was established under the Bretton-Woods monetary system in which currencies were pegged to gold. By 1971, the United States was running large balance of payment deficits which meant that massive amounts of dollars were leaving the country. These flows of dollars could not be sustained by the gold that we had in reserve. England finally told the United States that it would no longer accept the certificates the U.S. used in place of gold. On August 15, 1971, the Nixon Administration responded by taking the dollar off the gold standard and letting it float against other currencies. ANSWER: The dollar is the market. Under the Bretton-Woods system, there were queues of sellers of dollars who couldn’t get foreign countries to accept them. Here there is a surplus of dollars, and for the dollar the price control became a price floor. One of the side effects was that American manufacturers became far less competitive than the Japanese or Germans because our currency was overvalued. 4. Rent Controls. Many communities in the United States have rent controls. In places like New York, the controls have held rents down for so long, that landlords have not kept up their properties and renters cannot find apartments to rent. ANSWER: The market is rental apartments, and there are queues of buyers. This means there are shortages of apartments and rent controls take the form of price ceilings. One of the side effects is dilapidated rental housing. 5. DRGs. Diagnostic Related Groupings (DRG) are classifications that allow the government to determine the rate at which different kinds of medical procedures will be reimbursed. Since many people depend upon Medicare, Medicaid and other government programs the DRGs effectively set the price that can be charged. However, many HMOs withdrew from the Medicare program because government reimbursement rates were too low. This left many people without access to their doctors or without medical care. ANSWER: The market is the health care market, and there are queues of buyers who are not being served. This means there are shortages and the DRGs must be working as a price ceiling. The side effect is poor access and quality of care. Each of the cases in which shortages occurred were accompanied by market pressures to raise prices. People dealt in a black market, waited in a line, paid for someone else's place in line, sold ration tickets, or undertook a host of other costly techniques for counteracting the shortage. The effect of all of these activities was to raise the costs of buying the commodity. But while prices went up to ration buyers they did not benefit the sellers to eliminate the shortage. Each of the cases in which the surpluses occurred were accompanied by market pressures to lower prices. Businesses wanted to offer sales, sought alternative markets in which to sell the product, donated it for humanitarian purposes, or simply dumped it. Buyers, sensing their market power, became harder negotiators. Again black markets for the product appeared, but the black market price was under the list price or support price. The effect of all of these activities was to lower the price of the commodity. Prices generally went down to provide more product to buyers and lower incentives to suppliers, but if prices were not allowed to change the ill effects of the surplus persisted and intensified. The government's experience serves as a lesson for managers of private firms. Managers of private firms can make the same mistake as the government by imposing rigid formulas on pricing. They can induce shortages just as easily as the government can from rigid pricing. We continually see evidence of these private market shortages including the scalping that goes on at major playoff games, the crushing lines at major sports events and concerts, the long wait for the popular doctor, the nursing shortage, unavailability of household help and babysitters, the lines at bank teller and restaurant carry out windows, the crowding of highways, the over utilization of recreation facilities or parks, the overbooking of hotels, etc. SECTION 4. RETURN ON INVESTMENT In long run decisions about a new product or the continuation of an old product, managers often want to see how the return on investment on one product compares with the return on others. In doing so, the manager is assessing the opportunity cost of an investment. Suppose a 20% return can be earned on investments with similar risks elsewhere; then the manager might set a target rate of return (ß) of 20%. The price, determined on the basis of the target rate of return, depends upon the amount of invested capital (K) needed to produce the standardized volume (Q*) as follows: (4-1) P = UV + UF + ß*K/Q* Once again explicit costs are included in the standardized unit cost (UV+UF); implicit costs are covered by the satisfactory profit (ß*K/ Q*). If 10 units of a new product had a unit cost of $8, but $30 had to be invested to produce the item, then a profit of $6 (=20%*$30) would be needed to reach a 20% target rate of return. This would translate into a price of $8.60 per unit (=$8+($6/10 units)). There is one type of industry in which return on investment has been used extensively as a means to control prices; utilities, particularly electric utilities. From this industry we can learn a great deal about the difficulties price control and pricing using a target return on investment criterion. A. The Permitted Rate of Return A state's right to regulate utility rates was affirmed in 1877 by the Supreme Court in the case Munn vs. Illinois (94 U.S. 113 (1877)). But that decision also ushered in a century of squabbles about how to measure the return on investment. A utility regulator typically set a given "fair rate of return" for a utility. This fair rate of return, r, multiplied by the utility's investment (K) determined its maximum allowable profit: (4-2) allowable profit = r*K Generally, there was little problem determining the fair rate of return, r. The fair rate of return was often computed based on the return from market opportunities that were most similar in risk and value to those of the utility. A utility commission could choose a market rate of return for similar investments with similar degrees of risk. B. The Rate Base However, the level of investment, K, was the subject of extensive debate and legal wrangling. The problem was to determine how to measure a utility's investment, which was called its rate base. There are three theoretical approaches for measuring the rate base: (a) (b) (c) Original or "Historical" Value. As its name implies, a firm can value its capital based on the actual dollar cost- original cost- at which it was purchased. However, with inflation such a valuation understates the current value of the capital. Reproduction Value. If a utility wished to buy or sell its identical facilities on the market at current prices, it could compute the total current value or reproduction value of its facilities. This is the kind of value estimation that becomes important when a company is liquidated. However, since a utility is obligated to provide service, it does not accurately represent the cost of providing that service. Its current facilities are likely to be out-of-date. Comparable facilities may not be found on the market, and that makes valuation difficult. The firm would not attempt to buy the same facilities even if they were available, preferring instead to adopt the latest technology. Replacement Value. Ideally a firm would replace depreciated facilities with the latest technology. The replacement value is the current market value of the firm's capacity, based on the latest technology that would achieve the firm's current production capacity. If a utility commission were to restrict the firms under its jurisdiction to a method which resulted in too small a valuation of a firm's investment, profits and services would be squeezed, making further investment capital hard to raise. On the other hand, if the valuation were too high, the firm would make such high profits that its stock would be bid up and the utility would tend to overexpand. The Supreme Court tried to resolve the valuation problem before the turn of the century. In Smyth vs. Ames (169 U.S. 466 (1898)), it created the concept of "fair value" which failed to be specific and also provided a misleading suggestion about how fair value might be determined. The new "fair value" criterion was commonly interpreted as an average of the original and reproduction valuation methods, but it provided the basis for massive litigation. Finally, in Federal Power Commission et. al. V. Hope Natural Gas Co. (320 U.S. 591 (1944)), the Supreme Court got away from defining fair value. It left that up to the regulators as long as the regulatory decision process was "just and reasonable." Many of the regulators then adopted the flawed, but relatively simple original cost method of valuation of the rate base. But there was no common procedure amongst the regulators. Even if an adequate rate base is established, a rate of return control provides undesirable incentives for a utility. Once a commission has determined how it will measure the rate base, the utility has an incentive to spend as much money as possible to make the rate base larger. Expenditures on inputs such as labor which do not raise the rate base are likely to be held down. However expenditures on plant and equipment which are included in the rate base are likely to be favored. Economists have measured a bias toward excessive capital expenditure relative to expenditures on other factors. This bias is called the Averch-Johnson effect.1 But the effect is more easily remembered as “gold-plating.” 1 Harvey Averch and Leland L. Johnson, "Behavior of the Firm under Regulatory Constraint," American Economic Review 52 (December 1962): 1052-69. A good, though dated survey concerning this effect can be found in Elizabeth Bailey, Theory of Regulatory Constraint (Lexington, Mass.: Lexington, 1973) SECTION 5. PRICE DISCRIMINATION AND PEAK LOAD PRICING The problem with using any pricing formula as a rigid guideline is that the formula can interfere with the rationing function that prices should perform in a market economy. Prices serve as a market signal to buyers and sellers. Rising prices constrain buyers willingness and ability to buy and can therefore alleviate shortages. Falling prices enable sellers to clear out unwanted inventories that result from surpluses. If a firm is rigid in its pricing it may not be able to adjust its prices appropriately to eliminate surpluses or shortages. To be flexible enough to avoid shortages and surpluses, a firm may have to be skilled in adjusting prices rapidly. Even within the period of a single day, demand may fluctuate between peaks and valleys and a single price would exacerbate such fluctuations. In such circumstances a firm should be skilled at peak load pricing in which it charges higher prices for customers buying when demand is greatest. Different customers may have different capabilities to pay. A firm charging different prices based on customer ability to pay is using price discrimination to ration goods and services. Because governments have learned so much about these two pricing techniques from closely regulating utilities, we also will use utilities to learn about the conditions under which different prices should be charged within a single market. Figure 5-1. Peak Load Pricing Marginal Cost After expansion Price ($/000 Kwh) Marginal Expanded Capacity Cost Before expansion 7.5 5.0 Peak Price Before expansion Peak Price After expansion Marginal Cost = Off Peak Price Peak Demand Quantity (000s Kwh) 4 6 9 Off Peak Demand NOTE: With peak load pricing a firm can finance expansion to the point where peak and off-peak pricing will be the same. A. Peak Load Pricing Because of regulatory lag in granting price increases, inflation, or restrictions by regulators a utility company may find that there is a greater quantity demanded than it has the capacity to provide. This capacity shortage is likely to occur only at certain peak periods. Figure 5-1 shows the short run marginal cost curve of a utility which has the capacity to produce 6000 kilowatt hours of electricity. Notice that demand during peak periods of time is to the right of the demand at nonpeak periods. To ration the electricity efficiently, the utility should raise the price it charges to peak users to the point where demand intersects price (at about $7.50 per thousand KWh in the Figure). However, if such a price were charged for off peak users, the utility would drop its revenues as off peak sales drop from 6 to 4 KWh. The solution is to charge off-peak users the marginal cost of providing the electricity (at $5.00 per thousand KWh) and charge the cost of expansion to the peak users (at $7.50). Such a multiple price approach is called peak load pricing. The additional revenues from peak load pricing can be reinvested to expand capacity. When capacity is expanded enough to cover peak and off-peak demand, the price for the two services will converge. In Figure 5-1, the utility could expand to 9 KWh in order to eliminate the price differential. If a price regulator ignores peak load pricing, it can cause shortages resulting in brownouts or blackouts; before the utility expansion in Figure 5-1 such shortages would have occurred at any price below $7.50 for peak demand. B. Price Discrimination Peak load pricing is not the only rationale for charging different rates for different customers. Price discrimination occurs when customers are charged different prices for the same good or service, and when the difference in price is not related to differences in the cost of providing service. Three types of price discrimination are defined in economics: (1) Third degree price discrimination occurs when a firm can identify groups of buyers who can be charged different prices for the same product. (2) Second degree price discrimination occurs when a firm can charge different prices for additional increments of one product to a single customer (or single customer group). (3) First degree price discrimination occurs when a firm can charge different prices for each additional unit of output according to what each customer is willing and able to pay. A separate analysis is required for each of these three types of discrimination. 1. Third Degree Price Discrimination A utility can often segment its markets based on characteristics of its customers. The key to successful segmentation is the ability to prevent customers who are charged higher prices from disguising themselves to qualify for lower rates and to prevent them from buying from the customers who quality for lower prices. Airlines can successfully segment by giving lower rates to customers who can plan in advance. Utilities are able to differentiate between residential, commercial, and industrial users. Once an effective basis for market segmentation and the demand for each market segment has been found, the profit maximization rule can be applied. It requires the horizontal summation of marginal revenue curves of the separate markets to derive the marginal revenue curve for the combined markets. Figure 5-2 shows the hypothetical demand and marginal revenue for industrial (center) and residential (left) users. Assuming there are no commercial customers, we can derive the marginal revenue curve for offering service to both markets (right hand diagram). For each level of marginal revenue, the corresponding quantities in the residential and industrial market are added together to find the combined marginal revenue curve. The profit maximization condition requires that marginal revenue of the combined markets equals marginal cost. However, the pricing in the two markets must be separate. Theoretically to keep track of how to determine optimal production levels for two markets, a manager can follow the following four steps, as illustrated in Figure 5-2: Step 1. Find the combined output for each possible marginal revenue level.. For example, one market produces a marginal revenue of $3.00 per Kwh when 1800 Kwh is sold while in the other market only that marginal revenue occurs after only 700 Kwh is achieved. In the combined market the $3.00 marginal revenue is achieved with production of 2500 Kwh. If any more were produced marginal revenue would fall in both markets. Step 2. Graph the cumulative MR curve. At each marginal revenue level a graph of the cumulative marginal revenue curve can be constructed as shown on the right hand side of Figure 6-2. This graph is simply the horizontal sum of the outputs cumulated at each level of marginal revenue in the two markets separately. These individual markets are depicted in the left hand and center graphs. Step 3. MC= Cumulative MR. Using the new marginal revenue curve in the right hand graph, find where marginal revenue and marginal cost of the joint products are equal. This marks on the X-axis the profit maximizing output for the two goods. Step 4. Read the price off the demand curves in the individual markets. For the marginal revenue ($9.50) where MC=cumulative MR, go back to the individual markets and find the associated outputs and prices. Notice that the prices in the two markets are different. In one market, the demand curve associated with a marginal revenue of $3.00 corresponds to a price of $25.00, but in the other market the demand curve shows that the price would only be $20.00. The differences between the two markets reflect the differences in the elasticities of demand in the two separate markets. Figure 5-2 Horizontal Addition of Marginal Revenue 4a Price ($/ 000 Kwh Residential Marginal revenue Residential Price Price ($/ 000 Kwh 25.00 20.00 4b 9.50 3.00 Industrial Demand Industrial Price 1a Industrial Marginal revenue Price ($/ 000 Kwh Residential Demand Horizontal Sum of Marginal revenue MC=MR 1b Marginal cost 3 2 1.8 .7 2.5 Residential (Kwh) + Industrial (Kwh) = Total Marginal Revenue NOTE: Marginal revenue curves in the two market segments are added horizontally to arrive at the marginal revenue curve for the combined market. While a manager is not generally going to graph the marginal revenue and marginal cost curves jointly for joint products, the manager must be aware of the complex ways that the markets for joint products interact with each other and must realize how the price sensitivity (in other words, the elasticity) in the different markets requires different prices. By knowing the reasoning implicit in Figure 5-2, a manager is not embarrassed about charging different prices in different markets, but knows how to justify and explain why it is necessary to charge different prices if adequate rationing and optimal profit are to be achieved. With information about demand in each of its market segments a utility could determine what price to charge in each market. Given the price elasticity of demand, i, for each group, i, the profit maximizing output would be established by the following formula: (5-1) P = MC / (1 + 1/i ) It applies to each group (residential commercial) separately, rather than to a whole market. If allowed to discriminate in prices, a utility would need to know the price elasticity of demand for each of its groups in order to determine the appropriate price. Successful 3rd degree price discrimination can only be practiced in markets where a firm has the discretion to charge different prices and where it is possible to group customers into separate markets. In other words, a utility would not want to see residential users buying electricity indirectly from industrial users. Such secondary markets prevent successful market segmentation. Finally, the elasticities of demand must be different for each group. If the resources associated with price discrimination and the cost of market segmentation is greater than the revenue generated from price discrimination, then 3rd degree price discrimination may not be worthwhile. When new technologies such as micro-turbines allow customers to sell to other customers, a utility may lose profit potential by not knowing how to discriminate between different markets. 2. Second degree price discrimination In order to provide the amount of service required by customers, utilities may have to discriminate in prices in order to be profitable. Figure 5-3 shows a utility with a downward sloping long run average cost curve. Even if the average costs were not everywhere above demand, economies of scale would mean that the utility would face losses if it tried to price at marginal cost. (In chapter 8 with economies of scale we saw that marginal cost would be below average costs and price would therefore be below average cost). Allowing a firm to provide discounts for large quantity purchases can provide additional revenues without any increase in cost. Such quantity discounts appear everywhere from the factory to the grocery store. Because the prices vary with blocks of output 2nd degree price discrimination is often called block price discrimination. In declining block price discrimination the prices are lower for larger purchases. However, with environmentalist pressures and the inability to expand, utilities have sometimes been forced to eliminate such discrimination. In fact, if a utility could not expand even though demand were expanding it could eventually be forced to increasing block price discrimination. Figure 5-3. Block Price Discrimination Long Run Marginal Cost Price ($/ Kwh) Long Run Average Cost 7.5 6.0 5.0 Revenue added w/ Discrimination= =(7.5-5.0)*6= 15 Long Run Marginal Cost Demand Total Revenue= (5.0*9)=45 Total Cost = (6*9)=54 Quantity (Kwh) 6 9 NOTE: If the firm were only to charge one price of $5.00 per Kwh and were to produce 9000 Kwh, there would only be $45,000 of revenue which would be less than the costs ($54,000) of providing the electricity. But with second degree price discrimination, $15,000 more can be added. The first block of revenue consists of 6 KWh at a price of $7.50 for a revenue contribution of $45.00. The second block of revenue consists of 3 KWH at a price of $5.00 which contributes $15.00 of extra revenue. The utility in Figure 5-3 can increase its revenues by simply lowering its price for additional increments of output. In making a bid to install electric service, a utility might offer $7.50 for the first six thousand KWh and then offer $5.00 for the next three thousand KWh, as shown in Figure 5-3. Let's see how this pricing scheme would affect the utility's profits. Table 5-1. Revenue effects of Price Discrimination ============================================================ Block Discrimination No Discrimination (000/s) $/KWh $(000s) $/KWh $ (000s) ____________________________________________________________ 1st 6 KWh $7.50 $45.00 $5.00 $30.00 2nd 3 KWh $5.00 +$15.00 $5.00 +$15.00 Total Revenue $60.00 $45.00 Total Cost $6.00 -$54.00 $6.00 -$54.00 Profit (Loss) $6.00 -$9.00 Gain from Discrimination=-$6.00- (-9.00)= $15.00 ============================================================ NOTE: The price and revenue differ only for the first block of output. However, the extra revenue, $15.00, from discrimination allows the utility to take a profit rather than a loss. Raising the price $2.50 on the first 6000 KWh block generates another $15,000 (=6000*$2.50) of revenue as shown by the shaded area in Figure 5-3. With this extra discrimination, the utility can make a positive profit, rather than a loss. 3. First Degree Price Discrimination If the utility was allowed to charge every customer what each customer were willing and able to pay, then the utility would be using first degree price discrimination. Figure 5-4 shows that a utility which can use 1st degree price discrimination can capture the whole area- called consumer surplus- under the demand curve. In Figure 5-4, the consumer surplus is given by the triangle located between the demand curve and the price charged by the utility. This consumer surplus measures the potential revenue from charging all customers the maximum that each is willing and able to pay for each unit. Figure 5-4. First Degree Price Discrimination 10 Long Run Marginal Cost Price ($/000 Kwh) Long Run Average Cost 6.0 5.0 Revenue Added =Consumer Surplus =.5 (10-5)*9= 22.5 Long Run Marginal Cost Demand Total Revenue= (5.0*9)=45 Total Cost = (6*9)=54 Quantity (000s Kwh) 6 9 NOTE: The shaded triangle is the consumer surplus. Since the demand curve is linear, the area is given by the formula: consumer surplus = 1/2 * output * price difference = 1/2 * 9000 KWh * ($10.00-$5.00) = $22.50 With perfect information about consumer demand a utility could determine precisely what price to charge each customer for each unit of output. Given the price elasticity of demand, j, for each customer, j, the profit maximizing condition would be: (5-2) P = MC / (1 + 1/j ) By now this condition should be familiar. However, now it applies to each individual separately, rather than to a whole market or market segment. Allowed to discriminate in prices, a utility would want to know the price elasticity of demand of each of its customers in order to determine the appropriate price. With the ability to discriminate in price on every unit with respect to every customer, the utility in Figure 5-4 would be able to make a profit. At an output of 9000 KWh, total cost is $5400. Revenue without price discrimination would be only $4500 (=9000Kwh * $5.00). However, with first degree price discrimination, the utility can turn the full consumer surplus of $2250 (=(1/2)* 9000 Kwh* ($10.00-$5.00)) into additional revenue. Total revenue is therefore, $6750 (=$4500+$2250) and total profit is $1350 (=$6750-$5400). The utility is profitable with first degree price discrimination. Of course, the utility would have to prevent the consumers from getting together in any way to buy from each other, would have to find precise information on consumer demand, and would have to gain permission from regulators. These conditions are all violated for most utilities. SECTION 6. MULTIPLE PRODUCT PRICING: Tied Products Often businesses find that they can make a great deal of revenue by offering additional products, particularly if they have market power in one market. All they need to do is to require people who want the one (tying) product in which the company has market power to buy the other (tied) good off of which the company wishes to make additional revenue. Such a requirement was once illegal per se under the antitrust laws. However, for decades Economists questioned whether tying of goods could have any redeeming value. Firms have goods or services tied together for many reasons: (a) (b) (c) When a firm has market power in one market or has a commodity in short supply (tying good), it may be able to rid itself of a surplus or a commodity in which it has no market power (tied good). In airline travel, for example free upgrades to first class seats (tying good) is tied to the number of miles traveled through normally paid flights on an airline (tied good). When a firm introduces a new product, it may wish to ensure quality service so that the new product will build goodwill more quickly. While tying is often illegal,2 the Supreme Court3 recognized in a case involving an electronics company that tying service to a new product provided a reasonable use of tying. A firm can often use tying for the purpose of 1st degree price discrimination. Successful discrimination requires that the tied good must be used in proportion to a customer's need for the tying good (eg. a camera or copying machine). In chapter 10 we saw that photographic and copying companies like Xerox could gauge the needs of customers by the number of copies or photographs customers made. By taking revenues from the number of copies made or the number of photographs taken (tied good), the companies could set prices based on relative needs for copying services. This is a form of price discrimination. Because the demand for the tying good affects the demand for the tied good, they must be priced in 2 Section 3 of the Clayton Act makes such sales illegal if they substantially lessen competition. 3 United States v. Jerrold Electronics Corporation, 365 U.S. 567 (1961) tandem. EXAMPLE: Tying Home Health Care to Hospital Services Suppose the hospital offering home health care services began to find that there was stiff competition from other home health care agencies. They might decide to require anyone who is a member of the hospital’s network to use home health services provided by the hospital. Publicly they might claim that this would be the only way that they could ensure quality service. By making such a requirement, the hospital’s network becomes the tied good and the home health care becomes the tying good. Such a tying arrangement may force the hospital to supply the burden of proof in an antitrust case to show how their home health care would maintain quality while other home health services would not. In addition they would have the burden to show that the tying arrangement involves the least restrictiveness necessary to maintain quality. SECTION 7. CONCLUSION Price controls and inefficient pricing continue to characterize many markets. Private firms can be just as inefficient with centralized pricing as governments can be with price controls. Whenever a rigid formula or rule-of-thumb is applied to pricing it inevitably ignores the changes in underlying market conditions which can lead to shortages or surpluses. For example, the Post-office uses one price for a first class stamp, regardless of where a piece of mail is sent in the United States. While it might be more efficient to charge on the basis of the distance that a letter is sent, such a rigid formula might itself prove inefficient. For example, for decades the steel industry priced steel on the basis of the distance from certain key steel centers. Nothing points more clearly to the inefficiencies of such pricing schemes than the competitors like Fedex and UPS who come into a market and survive profitably under more flexible pricing schemes. While the last general price control program ended in the decade of the 1970s, price controls are growing in several industries. Most prominently they are appearing in the Health Care industry. Ironically it was during a conservative Republican administration when the first steps toward price controls were undertaken in the health market. Researchers at Yale University categorized diseases with a system called Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs) which were applied to hospitals. These categories allowed the federal government to set limitations on reimbursements through Medicare for patients with different diseases. Then in 1989 Harvard researchers established a similar system, the Resource Based Relative Value System (RBRVS), for physician reimbursement. Still more recently researchers designed an “APG” system to control reimbursements for ambulatory, home health, occupational therapy, and physical therapy care. Such categorization systems allow the government to control health care reimbursement. However, as in any price control, inadequate reimbursement leads to shortages of services. Increasingly, large groups of the population are finding shortages in health care coverage or quality of health care as a result. As such symptoms of disequilibrium worsen, the government will again need to step in to reform the health care market. While it is easy to start a price control program, past experiences have shown that it becomes very difficult to end such programs. But if private market pricing is also inefficient, there may be little choice but to rely upon government involvement. INDEX (tied) good................................................. 15 Averch-Johnson effect .............................. 7 black market .............................................. 4 block price discrimination ...................... 12 consumer surplus .................................... 14 disequilibrium ............................................ 3 equilibrium ................................................ 2 fair rate of return ...................................... 6 First degree price discrimination............. 9 original cost................................................ 7 peak load pricing ....................................... 8 price ceilings ............................................... 3 price discrimination .................................. 8 price floors.................................................. 3 rate base ..................................................... 6 replacement value ..................................... 7 reproduction value .................................... 7 Second degree price discrimination ........ 9 shortage ...................................................... 2 surplus ........................................................ 2 target rate of return .................................. 6 Third degree price discrimination ........... 9 tying) product .......................................... 15 white market .............................................. 4