COPYRIGHT QUIZ 1 MODEL ANSWER

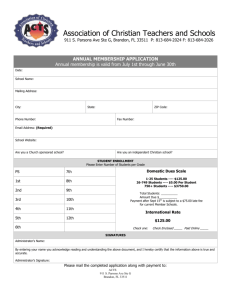

advertisement

COPYRIGHT QUIZ 1 MODEL ANSWER 1. The Channel Surfer 17 U.S.C. s. 102 sets out three requirements for copyrightable subject matter: (1) the work must be “fixed” in a tangible medium of expression; (2) it must be an “original work of authorship” and (3) it must be expression rather than idea. All of these requirements are probably met for Brandon’s work, yet due to a special provision of the Copyright Act, section 103(a), he will most likely be barred from copyrighting his work. Brandon’s work is clearly fixed in a tangible medium of expression, since it is an audiovisual work recorded on videotape. Brandon probably has exercised a minimal act of authorship in preparing the work. His work is a compilation of a number of television programs. The Copyright Act defines “compilation” in section 101 as: “a work formed by the collection and assembling of preexisting materials or of data that are selected, coordinated, or arranged in such a way that the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship.” It is also a derivative work since it is based on preexisting television programs. The Copyright Act s. 101 defines “derivative work” as: “a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted.” In the Supreme Court’s decision in Feist, the Court held that the only aspect of a compilation of preexisting materials that is copyrightable is its “selection and arrangement”, provided that that entails a minimal degree of creativity and is the independent action of the compiler. Feist stressed that the originality requirement “is not particularly stringent” and the “vast majority” of compilations will pass this test. The relevant question is whether there was a “creative spark” in what Brandon did that is more than “so trivial as to be virtually nonexistent.” On these facts, it appears that Brandon did exercise a minimal act of authorship. The selection or arrangement of works would qualify as copyrightable expression rather than idea. However, s. 103(a) of the Copyright Act provides that copyright protection cannot be obtained for compilations or derivative works that were created by unlawful use of underlying material. It appears likely that Brandon unlawfully used copyrighted television programs included in Brandon’s compilation tape. To determine this would require knowing more about the purpose and character of Brandon’s use (noncommercial or commercial?), the nature of the television programs included in Brandon’s tape, (fictional or factual?), the amount and substantiality of the programs that Brandon included nature and amount of these works that were included in Brandon’s tape, as well as the effect of Brandon’s tape on the market for the television programs that he included in his compilation. See s. 107 (since we haven’t studied the issue of lawful use yet, I would not expect any substantial analysis of this issue, or even a cite to s. 107, but I did expect you to be able to apply s. 103(a)). Even if Brandon lawfully used the copyrighted television programs, and thus was able to claim copyright in his compilation, the extent of copyright protection that he would obtain would be very “thin”. See Feist. Brandon could only claim copyright protection for the original selection and arrangement of the underlying works and not in the content of the works themselves. See 17 U.S.C. s. 103(b) (which states that: The copyright in a compilation or derivative work extends only to the material contributed by the author of such work, as distinguished from the preexisting material employed in the work, and does not imply any exclusive right in the preexisting material. The copyright in such work is independent of, and does not affect or enlarge the scope, duration, ownership, or subsistence of, any copyright protection in the preexisting material”) Thus, it would generally be difficult for Brandon to successfully claim that other compilations of these television shows infringed his copyright, unless they were exact or virtually exact copies of his selection or arrangement. This means that Brandon’s copyright would most likely be of limited practical use. 2. The Law School Lecture Professor Fischer’s impromptu lecture is not copyrightable because it fails to satisfy the fixation requirement set out in 17 U.S.C. s. 102(a), which requires a work to be “fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which [it] can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.” Section 101 defines a “fixed” work as “when its embodiment in a copy or phonorecord, by or under the authority of the author, is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.” Since it appears from the facts provided that Professor Fischer has not written down or otherwise recorded her lecture in any tangible medium, but delivers it for the first time on a totally impromptu basis, the fixation requirement is not met and it will not be copyrightable unless and until she records it in a tangible medium of expression. It makes no difference to the lecture’s copyrightability if Sam Student records the lecture without Professor Fischer’s consent. The definition of fixation in 17 U.S.C. s. 101 includes a requirement that the work be fixed with the authority of the author. (See above). That requirement has not been met on these facts; thus Sam Student’s taping does not satisfy the fixation requirement. Nor does it make any difference to the lecture’s copyrightability if two students, Edwin Eager and Greg Gradegrubber, take copious (but not verbatim) written notes. If they are doing so without Professor Fischer’s consent, the note taking would not serve to fix the work, on the same analysis described above for Sam Student’s recording. If they take notes with Professor Fischer’s consent, the fact that their notes are not verbatim would also not effectuate a fixation of Professor Fischer’s lecture because they are not fully recording Professor Fischer’s lecture, but their own expression of the ideas in Professor Fischer’s lecture. 2. The Mount Vesuvius Fireplace [Slightly edited Student Answer] Molly can copyright the fireplace if she can effectively assert that the fireplace is a sculpture since Section 102(a)(5) of the Copyright Act explicitly includes sculptural works as a category of copyrightable works. She would have to overcome the contention that a fireplace is merely a useful article. Section 101 includes the following caveat in the definition of “pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work”: “The design of a useful article . . . shall be considered a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work only if, and only to the extent that, such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” Thus, the primary issue that must be resolved to determine whether the fireplace is copyrightable is whether the sculptural features of the fireplace are conceptually separable from the utilitarian aspects of the fireplace. There are four tests that have been advanced by courts for determining whether a functional article is copyrightable. The Kieselstein-Cord test considers which function is primary and which is secondary. Second, the Brandir test states that “where design elements can be identified as reflecting the designer’s artistic judgment exercised independently of functional influences, conceptual separability exists.” Under the test of the majority in Carol Barnhart, there is no conceptually separability where the claimed artistic features are inextricably intertwined with the utilitarian features. Finally, Judge Newman, dissenting in Barnhart, suggested a test based on the mind’s eye of the ordinary observer. This test asks whether the ordinary observer can separate the utilitarian and non-utilitarian aspects of the work. Regardless of which test is applied, considering that the fireplace has been assessed to be “of museum quality”, it should certainly be protected by copyright law. The primary function, like the belt buckle in Kieselstein-Cord, should be deemed to be in its artistic merit, not in the fact that it could serve as a functioning fireplace. Plenty of artistic judgment was involved that does not seem dictated by functionality, so the Brandir test should apply. The artistic features of the fireplace do not seem to be “inextricably intertwined” with the functional features, so the majority test in Barnhart would be satisfied. Finally, an ordinary observer could separate the utilitarian and nonutilitarian aspects of the work, so the test of Judge Newman would be satisfied.