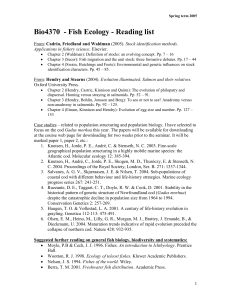

March 2, 2001 Mr. Louis Chiarella Essential Fish Habitat

advertisement

March 2, 2001 Mr. Louis Chiarella Essential Fish Habitat Coordinator National Marine Fisheries Service 1 Blackburn Drive Gloucester, MA 01930 Dear Mr. Chiarella, Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the Essential Fish Habitat components of the Northeast Multispecies and Atlantic Sea Scallop Fishery Management Plans (FMP’s). These comments represent my opinion. Firstly, I am somewhat puzzled by the Scoping Document where the statement is made that the Scoping Document initiates the formal FMP/EIS development process. I have attended over 47 meetings in the last two years that worked towards, to one extent or another, development of a Scallop Amendment. Habitat issues were a major concern during these meetings. Many alternatives were considered and analyzed that would and did mitigate impacts by scallop fishing gear on habitat and the species complex using that habitat. I think there needs to be a clarification by NMFS on what exactly is the process that will be followed. My primary concern with the existing EFH process is the presumption that observed impacts on EFH are adverse thus requiring some sort of mitigation. While it may be considered precautionary by some people to make such presumptions, in fact it can be, and has been, highly destructive to the fisheries management process and counterproductive to the goal of protecting EFH. I will focus my remarks on scallop dredging but in most instances these comments apply to other mobile gears as well. Scallop dredging is not a new fishing practice. Scallop dredging and other mobile gear activities have been taking place on the Georges Bank fishing grounds for over 100 years. In fact, other fishing activities that have the potential to disrupt ecosystems, by selective harvesting, have been underway on these grounds for over 500 years. The over-harvest of Atlantic halibut by hook fishermen in the last century is just one example. The removal of such a large biomass of halibut from the Georges Bank ecosystem had to totally change the habitat/species complex from what had previously existed. The current practice of the recreational charter boat hook fleet of targeting “mother cod” may be the biggest threat to this species with resulting EFH impacts. Fishing effort by hook gear for large cod has in all likelihood altered species composition and abundance with possible adverse impacts to cod stocks, biodiversity, and other aspects of the existing ecosystems. The rush to judgement on what constitutes important EFH may have substantial negative impacts on ecosystem management. For example, NMFS has designated the northern portion of Groundfish Closed Area II (CAII) as an HAPC for cod with minimal scientific evidence. The HAPC extends as far east as 67 00' (the Hague Line), north to 42 10', west to 67 15' and as far south as 41 50'. This HAPC encompasses areas that have been important cod and scallop fishing grounds for this century and possibly many previous centuries. In the last seventy years mobile gear, otter trawls and scallop dredges, have been the dominant harvesting tools on these grounds. The relatively recent reduction in cod abundance in no way implies that the existing fishing practices have a substantial adverse effect on this particular EFH. The slow rebuilding of cod stocks may have more to do with the loss of large spawners harvested by the new charter boat hook fishery than lack of rocks for juveniles to hide under. It is a relatively easy to make the argument that mobile gear impacts habitat in many ways. It is also easy to document that virtually all habitats that man has routinely encountered have been altered in some fashion and many values have been lost or gained. These issues are beside the point. The fundamental question is that given an altered habitat, how do we best achieve all the goals of fisheries management. At this point in time, management authorities are not proposing an outright ban on mobile gear. There are many good reasons for this policy. However, there is a willingness to limit mobile gear in certain areas for habitat considerations, such as the HAPC for cod. This concept can be described as the ‘let the bottom grow back’ theory. On the surface this theory may seem to be a logical precautionary approach. One significant consequence of closing an area to mobile gear is that it shifts the fishing activity to other locations which may be more essential. Shifting effort to passive gears, hooks and gill nets, capable of fishing hard bottom that mobile gear can not access, may be detrimental to cod rebuilding efforts. The Cod HAPC The Amendment for Essential Fish Habitat establishing the cod HAPC references a number of scientific documents to build the case for the designation. The stated objective of the HAPC is to improve the survival of juvenile cod. The cod HAPC encompasses one of the most important and traditional fishing grounds of the sea scallop fleet. Any regulatory attempt at restricting mobile gear in this area has significant economic impact on the scallop fleet. Moreover, the designation has shifted effort to more complex ecosystems. A closer examination of the Council’s argument needs to be made. Any regulatory action with such significant consequences must be based on sound science and reliable information, not driven by research agendas and false public perceptions. The use of selective science to present one side of an issue in a public document is wrong. My fear is that the desire of habitat scientists to make use of a research opportunity has overly impacted their analysis. I need to present a detailed examination of the issue, only using same scientific references cited in the existing Amendment, to demonstrate my point about selective science. The EFH Amendment document states “Several sources document the importance of gravel/cobble substrate to the survival of newly settled juvenile cod”. The document further explains that a “A substrate of gravel or cobble allows sufficient space for newly settled juvenile cod to find shelter and avoid predation” The underlining is added here for emphasis. References for these statements are Lough et al, 1989; Valentine and Lough, 1991: Gotceitas and Brown, 1993; Tupper and Boutilier, 1995; and Valentine and Schmuck, 1995. The above analysis groups gravel and cobble habitat as having the same impact on juvenile cod survival. The references utilized do not confirm this similarity. Gotceitas and Brown (1993) conducted tests with juvenile cod on three substrates; sand, gravel-pebble, and cobble. Their results were “With no apparent risk of predation, juvenile cod preferred sand or gravel-pebble. When cobble was present, juveniles hid in the interstitial spaces of the substrate in the presence of a predator. With no cobble present, juveniles showed no preference between sand and gravel-pebble, and did not seek refuge from predation in association with these substrates.” Their conclusion.... ”these results demonstrate that neither sand nor gravel-pebble were viewed by cod as offering safety from predation.” Based on this reference the EFH Amendment conclusion that gravel provides shelter for juvenile cod is not supported. The EFH Amendment also uses Tupper and Boutilier (1995) to connect gravel and cobble together. Their study found that cod survival was highest on rocky reefs and cobble bottoms. Their study looked at four substrate types; sand, seagrass, cobble, and rocky reef. There was no gravel substrate identified in their study. This reference thus does not support the conclusion about gravel substrate. Lough et al. (1989) hypothesize that the gravel habitat favors juvenile cod survival through predator avoidance. There is no proof of this hypothesis or as stated by Gotceitas and Brown (1993) “In their study, Lough et al. (1989) attribute the distribution of juvenile cod among substrate types to a response by the juveniles to reduce the risk of predation, but no direct evidence for this interpretation was provided.” In fact Lough et al. (1989) report one of the two concentrations of juveniles found in late July 1987 as being in an area of varied bottom types which does not confirm their hypothesis. This study is far from documenting the importance of gravel substrate as stated in the Amendment document. Trawl studies identified by Lough et al did find juveniles on sand bottom during August. The more logical explanation for their observations is that on gravel substrates juvenile fish are broadly dispersed and easier to find while over sand bottom the juveniles are tightly schooled and thus hard to find. Schooling over sand bottom may in fact offer more protection from predation. Valentine and Lough (1991) do not provide any documentation of the importance of gravel substrate for juvenile cod survival. In fact, their study ends with a series of unanswered questions one of which is “Do untrawled areas of the bank, especially the gravel habitat, serve as refuges for juveniles and breeding adults that are important in sustaining a heavily utilized fishery.” A good question, but certainly not documentation! The Amendment document tries to establish that there is an ecological bottleneck due to the fact that there is high predation on juvenile cod, but offers no references documenting the existence of this bottleneck. They Cod HAPC meets the first classification criteria (i) as it provides suitable habitat. The references show that in all likelihood it is the cobble and boulder bottom that provides protection from predation. Lough et al. (1989) speculate that the gravel substrate may provide a background that “ softens fish silhouettes and obscures movement that predators cue on.” Fishing activity does not alter this background but may in fact enhance the mottled backdrop. As stated by Lough et al. (1989) “The dredging and trawling activity may help create the gravel seabed by mixing the sediment and allowing the gravel to migrate upward through finer sediment to become concentrated at the surface.” Auster et al (1996) confirm this observation on Jeffreys Bank; that after fishing “...much of the thin mud veneer was missing, exposing more of the gravel base..” There is an important management reason to differentiate between gravel bottom and cobble/boulder bottom. Fishermen, especially scallop fishermen, do not want to tow on cobble/boulder bottom. This is confirmed by the observations made by Valentine and Lough (1991). The commercial scallop concentrations that the fishermen prefer to harvest on the northern portion of the bank are on gravel and gravel/sand. There is no indication that fishing disrupts this bottom at the expense of juvenile cod survival based on the references used to establish criteria (i). The EFH Amendment document goes on to state that “Specific areas on the northern edge of Georges bank have been extensively studied and identified as important areas for the survival of juvenile cod. These studies provide reliable information on the location of the areas most important to juvenile cod and the type of substrate found in those areas.” References used for this statement are Lough et al., 1989; Valentine and Lough, 1991; and Valentine and Schmuck, 1995. It is important to not that for the most part these studies did not take place in the Cod HAPC but were in fact to the east in Canadian waters (Lough et al., 1989). These Canadian waters have virtually all the patches of cobble and boulder when compared to US waters (Valentine and Lough, 1991). It is my contention that it is these cobbles and boulders that make those sections of the gravel pavement important to survival of juvenile cod. The remaining portion of the argument for the establishment of the cod HAPC is built around the observation that scallop dredging “...reduces habitat complexity and removes much of the emergent epifauna.” The EFH document then implies that scalloping activity, by reducing the emergent epifauna, impacts juvenile cod “...survivability and readily available prey.” Again, the document’s own references do not all support this argument. Specifically, Gotceitas and Brown (1993) report that for offshore ecosystems typical of our region “...habitats characterized by the presence of upright forms of vegetation are rare, and variation in habitat complexity is primarily related to the size and composition of the mineral substrates present.” While bryozoans and hydroids are not vegetation, the similar attribute of vertical height is what the document is implying as being the important parameter. Collie (1998) refers to these animals as being “plant-like”. Tupper and Boutilier (1995) reported that newly settled cod “...were not closely associated with vegetation, but sought refuge within the interstices of rocks, shells, and other hard bottom.” In discussing the importance of habitat complexity on survival they indicate that complex habitats may have very high predator densities resulting in higher predation mortality compared to less complex habitats. Less complex habitats in temperate climates may produce “...fewer, larger recruits, each with a relatively high chance of survival.” Complexity in temperate marine systems is provided by water masses, such as cold water upwelling or warm core rings. This is different than tropical marine systems where bottom topography plays a key role. In the tropical marine systems reefs are considered “live bottom” and the sand areas between them are considered “dead bottom”. Yet, in temperate marine systems, the flat relatively featureless sand/gravel substrates produce tens of millions of metric tons of commercial harvest annually. The EFH document is overly concerned with substrate characteristics and virtually ignores all other oceanographic features. The EFH document has not explored all the options for habitat management. In the long term the scallop industry would benefit by controlling where the scallops set and how to most appropriately harvest the crop. In the meantime, some of our most important production areas are of mixed substrate; gravel bottom with patches of cobble and boulder. There is a need to examine alternative gear, i.e. lightly constructed dredges, as a means to protect habitat in mixed substrate scallop production areas. Dredges of this design would be capable of being towed on flat sand/gravel substrates but would have a high risk of being lost on cobble or rock strewn areas. This alternative will eliminate large fishing area closures to protect small areas of critical habitat and is highly enforceable. However, this approach is not currently available for implementation. The EFH components of the existing FMP’s suggest that newly settled juvenile fish have increased chances of survival on complex seafloor habitat. If this is the case, there is more than one management option. The one most advocated by preservationists is to close such grounds to fishing, ie, non-extractive reserves. But why is there increased survival? Is it shelter from predators? Food availability? If this is the case then an alternative would be to create more shelter (ie, artificial reefs) and harvest predators; weed and feed. A related alternative would be to increase and enhance the growth of dense epifauna and related communities by active intervention (ie, seeding). These are certainly alternatives that should be considered by NMFS. Two other points are important to keep in mind. One is that the number of predators in an area is important on assessing juvenile survival. Secondly, hard bottom boulders may act as fish aggregation devices (FAD’s) attracting large schools of predators to the vicinity. Hard bottom, similar to some artificial reefs might not increase abundance; just aggregate it. The most tried and true method for reducing fishery impacts is to increase catch per unit effort. In the scallop fishery this can be accomplished by a rotational area management strategy. The Nantucket Lightship Closed Area scallop fishery under scallop Amendment 13 is a fine example of what can be achieved. Failure of NMFS and the NEFMC to reopen the Georges Bank Groundfish Closed areas to a limited access scallop program, similar to the Amendment 13 program, has been detrimental to achieving EFH objectives. The best action NMFS can take to minimize effects (possibly adverse) of scallop fishing activities is to open areas of dense scallop concentrations. Sincerely, Ronald Smolowitz Collie, J.S., G.A. Escanero and P.C. Valentine. 1997. Effects of bottom fishing on the benthic megafauna of Georges Bank. Mar. Eco. Prog. Ser. 155: 159-172. Collie, J.S., G.A. Escanero, L. Hunke and P.C. Valentine. 1996. Scallop dredging on Georges Bank: photographic evaluation of effects on benthic epifauna. ICES C.M. 1996. Collie, J.S. 1998. Studies in New England of fishing gear impacts on the sea floor. In Effects of Fishing Gear on the Sea Floor of New England. Conservation Law Foundation, Boston:53-62. Gotceitas, V. and J.A Brown. 1993. Substrate selection by juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua): effects of predation risk. Oecologia 93: 31-37. Gotceitas, V., S. Fraser and J.A Brown. 1997. Use of eel grass beds (Zostera marina) by juvenile Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 54(6): 1306-1319. Lough, R.G. and D.C. Potter. 1993. Vertical distribution patterns and diel migrations of larval and juvenile haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) and Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) on Georges Bank. Fish. Bull. 91: 281-303. Lough, R.G., P.C. Valentine, D.C. Potter, P.J. Auditore, G.R. Bolz, J.D. Neilson, and R.I. Perry.1989. Ecology and distribution of juvenile cod and haddock in relation to sediment type and bottom currents on Eastern Georges Bank. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 56:1-12. Tupper, M. and R.G. Boutilier. 1995. Effects of habitat on settlement, growth, and postsettlement survival of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 52(9): 1834-1841. Tupper, M. and R.G. Boutilier. 1995. Size and priority at settlement determining growth and competitive success of newly settled Atlantic cod. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 118: 295-300. Valentine, P.C. and E.A. Schmuck. 1995. Geological mapping of biological habitats on Georges Bank and Stellwagen Bank, Gulf of Maine region. In Proceedings of 8th Western Groundfish Conference, Workshop on Applications of Sidescan Sonar and Laser Line Systems in Fisheries research: Alaska Department of Fish and Game Special Publication. Valentine, P.C. and R.G. Lough. 1991. The sea floor environment and fishery of eastern Georges Bank. Department of Interior, U.S. Geological Society, Open File Report 91-439. Auster, P.J., R.J. Malatesta, R.W. Langton, L. Watling, P.C. Valentine, C.L.S. Donaldson, E.W. Langton, A.N. Shepard, and I.G. Babb. 1996. The impacts of mobile fishing gear on sea floor habitats in the Gulf of Maine (Northwest Atlantic): Implications for conservation of fish populations. Rev. Fish. Sci. 4: 185-202.