L7: Ideal Members

advertisement

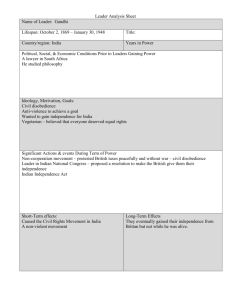

MVE6030 The Good Society and Its Educated Citizens Topic 5 (Lecture 7) The Ideal Membership of the Good Society: Citizenship and/or Nationality (I) Citizenship: Membership in Modern Political Communities (i) A. Citizenship: It refers to the ideal-typical membership endowed with subjects of a sovereign modern state. 1. The conceptions of the modern state: a. Max Weber’s conception: “A state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory. Note that ‘territory’ is one of the characteristics of the state. Specifically… the right to use physical force is ascribed to other institutions or individuals only to the extent to which the state permits it. The state is considered the sole source of the ‘right’ to use violence.” (Weber, 1946, p.78) b. Charles Tilly’s conception: “An organization which control the population occupying a definite territory is a state insofar as (1) it is differentiated from other organizations operating in the same territory; (2) it is autonomous; (3) it is centralized; and (4) its division are formally coordinated with one another.” (Tilly, 1975, p.70) c. Accordingly, the modern state can be defined as a set of power apparatuses, which can constitute effective rules internally and externally over a definitive territory and the residents within it. Hence, the modern state consists of the following constituent features i. the definitive territory ii. the definitive subjects iii. monopoly of use of physical force, i.e. sovereign power iv. the establishment of external and internal public authority 2. The conception of citizenship: a. Reinhard Bendix defines citizenship as individualistic and plebiscitarian membership before the sovereign and nation-wide public authority b. Its development signifies “the codification of the rights and duties of all adults who are classified as citizens”. (Bendix, 1964, p.9) c. Accordingly, citizenship can be defined as institutionalized relationships between the state and its legitimate subjects, i.e. citizens. These relationships consist of citizens’ definitive rights and obligations towards the modern state. B. Ronald Dworkin’s liberal conception of citizenship rights: 1. Rights as trumps: Dworkin suggests, “Rights are best understood as trumps over some background justification for political decision that states a goal for the community as a whole.” (Dworkin, 1984, P.153) More recently he underlines, “Political rights are trumps over otherwise adequate justifications for political decision.” (Dworkin, 2011, P. 329) Accordingly, in conceptualizing the idea of political rights of citizens, we are to enquire the question: “What kind of rights do W.K. Tsang Good Society and its Learnt Members 1 we each as individuals have against our state―against ourselves collectively?” (Dworkin, 2011, P. 328) 2. Two basic principles of legitimacy: Dworkin suggests that a state and its government can impose a collective and coercive decision upon its citizens unless it subscribes to two reigning principles. He states, “No government is legitimate unless it subscribes two reigning principle principles. First, it must show equalut concern for the fate of every person over whom it claims dominion. Second, it must respect fully the responsibility and right of each person to decision for himself how to make something valuable of his life.” (Dworkin, 2011, P. 2) 3. In accordance to these two principles of equal concerns and respects, Dworkin underlines that “governments have a sovereign responsibility to treat each person in their power with equal concerns and respect.” (Dworkin, 2011, P. 321) In light of Dworkin’s conceptions of political rights as trumps of citizens over the sovereignty of the state, the development citizenship rights can be approached in the following two perspectives, namely historical-sociological perspective of T.H. Marshall and Wesley Hohfeld’s jurisprudential (legal-philosophical) perspective. C. T.H. Marshall’s Thesis of Development of Citizenship Rights 1. Contradictory trajectory of development of capitalism and citizenship a. Capitalism is an institution based upon the principle of inequality, which is in turn built on uneven distribution of property and/or property right b. Citizenship is an institution based upon the principle of equality, which is built on equal citizen status and its derivative rights 2. Development of citizenship is construed by Marshall as means of abating social class conflict 3. The historical trajectory of development of citizenship rights a. Development of civil rights in the 18th century and the constitution of the Court of Justice and the Rule of Law b. Development of the political rights in the 19th century and the constitution of the parliamentary system and the democratic state c. Development of the social rights in the 20th century and the constitution of the social service departments and the welfare state D. Wesley Hohfeld’s Conception of Rights 1. Rights as Liberties 2. Rights as Claims 3. Rights as Powers 4. Rights as Immunities 5. Classification of Citizenship Rights with Hodfeld’s conception W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 2 (Janoski, 1998) W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 3 E. The theory of citizenship obligations 1. Conception of citizenship obligations: The concept of citizenship obligation can be discerned as the rights of the state in forms of claims or powers to its citizenship. “Citizenship obligations may range from the sometimes vague but other times enforceable requirement to respect another person’s opinion and position in life (i.e. general tolerance) to state-enforced civil obligations including conscription and taxation under the penalty of imprisonments.” (Janoski, 1998, p. 54) 2. Typology of citizenship obligations: a. “Supportive obligations consist of paying taxes, contributing to insurance-based funds, and working productively.” b. “Caring obligations to others and to oneself require a person to respect others’ right, care for children and a loving family, and respect oneself by pursuing an education, a career, and adequate medical care.” c. Service obligations include efficiently using service, and actually contributing services - be it voter registration, health care for the elderly, ‘pro bono’ work in public defense for lawyers, volunteer fire fighting, on youth service.” d. Protection obligations involve military service, police protection, and conscription to protect the nation by bearing arms or caring for the wounded, and social action to internally protect the integrity of a democratic system through social service, protests, or demonstrations.” 3. Approaches to the justification of citizenship obligations a. The contractual and instrumental approach: Obligations are conceived as returns to recipience and acceptance of rights b. The community-based and legitimacy approach: This approach avoids the narrowly instrumental approach to citizenship obligation and asserts that “some obligations do not entail rights” and discerns obligations with the concept of “general exchange, which underlines “people helping people who help other people.” (p. 61) The approach claims that most citizens do not calculate a right-obligation exchange on daily bases but tend to adopt a ‘generalized exchange’ stance, in which “people do not expect immediate and reciprocal returns form the people they help, but they do expect to see their returns materialize over time in building a decent life in a more or less just society.” (p. 61) c. Limiting obligation approach: This approach sees citizenship obligations claimed or enforced by the state upon its citizens may in conflict individual citizens’ rights. For example individual citizens’ rights to smoke in public venues are in conflict with the rights of the public to be free from environments hazardous to health. Hence, this approach asserts that in order to safeguard the violation of individual citizens’ rights, the state could demand its citizens to oblige only under four conditions: (p. 64) i. there is a clear danger, ii. no reasonable exist, iii. the decisions in favor of society are least intrusive, and iv. effectors are made to minimize damage or treat the effects of constraining a right. W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 4 W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 5 F. The Theories of Citizen Virtues: 1. Criticism of “vote-centric” democracy: a. The intrinsic dilemma of liberal democracy: C.B. Macpherson underlines at the opening page of his oft-cited work The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy, “If liberal democracy is taken to mean …a society striving to ensure that all its members are equally free to realize their capacities. … ‘Liberal’ can mean freedom of the stronger to do down the weaker by following market rules; or it can mean equal effective freedom of all to use and develop their capacities. The later freedom is inconsistent with the former. …The difficulty is that liberal democracy during most of its life so far …has tried to combine the two meanings.” (Macpherson, 1977, P. 1) b. The degradation of citizenship: The development of liberal democracies in capitalist societies, especially those in Europe and North America, in the twentieth century witnessed the degradation of the ideal-typical conception of democratic citizen, who is supposed to be rational, reasonable, responsible, and active participants in political decision-making processes in particular and public affairs in general. With the rise of welfare state and politics of seduction, citizens have been indulged and relegated to become clients of the welfare states, consumers of welfare service, desire-seeking free-riders in politics of seduction, and spectators of politics of scandal in mass media. c. The constitution of the “vote-centric” democracy: “In much of the post-war period, democracy was understood almost exclusively in terms of voting. Citizens were assumed to have set of preferences, fixed prior to and independent of the political process, and the function of voting was simply to provide a fair decision-making procedure or aggregation mechanism for translating these pre-existing preferences into public decisions, either about who to elect or about what law to adopt. But it is increasingly accepted that this ‘aggregative’ or ‘vote-centric’ conception of democracy cannot fulfill norms of democratic legitimacy.” (Kymlicka, 2002, P.290) 2. Theorizing deliberative democracy or “talk-centric” democracy a. To overcome the shortcomings of “vote-centric” democracy, numbers of social scientists and political philosophers have advocated alternative models of democracy to rectify if not replace the prevailing “vote-centric” democracy. One of these is the deliberative democracy, which aims to bring genuine and engaging talks and deliberations among reasonable citizens back into the decision-making processes in democracy. b. What is deliberative democracy? Amy Gutmann and Dennis Thompson define “deliberative democracy as a form of government in which free and equal citizens (and their representatives), justify decisions in a process in which give one another reasons that are mutually acceptable and generally accessible, with the aim of researching conclusions that are binding in the present on all citizens but open to challenge in the future.” (Gutmann and Thompson, 2004, P. 7) c. From this definition, Gutmann and Thompson underline four essential characteristic of deliberative democracy. These are i. Reason-giving: “Most fundamentally, deliberative democracy affirms the need to justify decisions made by citizens and their representatives. Both are expected to justify the laws they would impose on one another. In a democracy, leaders should therefore give reasons for their decisions, and respond to reasons that citizens give in return.” (Gutmann & Thompson, 2004, P. 3) Furthermore, reasons put forth and accepted in the W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 6 decision-making process of the deliberative democracy are not confined to “procedural” reasons and justifications but also include “substantive” reasons and justification. In this reason-giving and reason-justifying process, it is expected that understanding, reciprocity, and cooperation can be faired among most if not all parties concerns. ii. Accessible: “A second characteristic of deliberative democracy is that the reasons given in this process should be accessible to all the citizens to whom they are addressed.” (Gutmann & Thompson, 2004, p. 4) In order to input reasons and justifications into the democratic deliberation and make them accessible to all citizens, these reasons must be presented in comprehensible forms and the deliberations must take place in public. iii. Binding: “The third characteristic of deliberative democracy is that its process aims at producing a decision that is binding for some period of time.” (Gutmann & Thompson, 2004, P. 5) Talks taken place in deliberative democracy are essentially different from conventional political debates and arguments, in which engaging parties are simply try to impose their preferences and reasons on their opponents in a winner-take-all manner. The primary aim of talks in the deliberative democracy is consensus building and reciprocity constituting so that conclusion can be researched and decision can be made that will have binding effects on all citizens. iv. Dynamic: The fourth characteristic of deliberative democracy is that the process of deliberation itself should be dynamic and continuous. “Although deliberation aims at a justifiable decision, it does not presuppose that the decision at hand will in fact be justified, let alone that a justification today will suffice for the indefinite future. It keeps open the possibility of a continuing dialogue.” (Gutmann & Thompson, 2004, P. 6) 3. Conception of the virtues of citizens a. Reconceptualization of citizenship: In view of the shortcomings of the vote-centric democracy and politics of seduction, scholars begin to extend the discourse on citizenship beyond the right-based and obligation-based conceptions. They begin to enquire the necessary skills, performances and dispositions required of citizens in democratic processes. Numbers of scholars have characterized this dimension of democratic citizenship as virtue of citizen or simply civic virtue. b. William A. Galston underlines that one of the structural tension in liberal democracy is “the tension between virtue and self-interest.” (1991, P. 217) More specifically, it is the tension between two dimension of citizenship in liberalism. One the one hand is the “interest-based” citizenship rights and on the other the virtues required of democratic citizens. Galston has characterized four types of civic virtues which he thinks are instrumental the function of liberal democracy. They are (Galston, 1991, Pp. 221-7) i. General virtues: They include courage, i.e. “the willingness to fight and even die on behalf of one’s country” (P. 221); law-abidingness; and loyalty, i.e. “the developed capacity to understand, to accept, and to act on the core principles of one’s society” (P. 221). ii. Virtues of liberal society: They include virtue of independence, i.e. “the disposition to care for, and take responsibility for, oneself and to avoid becoming needlessly dependent on others” (P. 222); and the virtue of tolerance, i.e. “the relativistic belief that every personal choice, every ‘life plan’, is equally good, hence beyond rational scrutiny and criticism.” (P. 222) W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 7 iii. Virtues of liberal economy: They include entrepreneurial virtues, i.e. enterprising dispositions such as “imagination, initiative, drive, determination” (P. 223); and organizational virtues of employee, i.e. traits such as “punctuality, reliability, civility toward co-workers, and a willingness to work within established frameworks and tasks.” (P. 223) iv. Virtues of liberal politics: They include basically the disposition and capacity of reasonableness and tolerance. The former include willingness and capacity to engage in public discourse with communicative rationality and ethics as Habermas has underlined (See Lecture Note on Lecture 4 and 5, E.5.c). The latter include the willingness and capacity to respect viewpoints which are in opposition to one’s own; and readiness and capacity to “narrow the gap” among disagreements and antagonism or even the ability to arrive at a consensual resolution. (see also Benjamin Barber, 1999) G. The Obligation and Virtue to Disobey: The Conception of Civil Disobedience 1. Civil disobedience has been one of the important topics within the discourse of citizenship because it overlaps all three dimensions of citizenship, namely a. Civil disobedience as citizen right: It is argued that citizens has the liberty not to comply to policy that they consider to be wrong, unwise or damaging; to law that they think to be unjust; and even law and policy that are in opposition to one’s conscience. b. Civil disobedience as citizen obligation: The argument can elevate to the level that it is not one’s liberty or discretion to opt for noncompliance but one’s obligation that one, as citizens of a democratic state or even as a conscientious agent, has to act against a policy or legislation that is wrong, unjust, unethical or inhumane. c. Civil disobedience as citizen virtue: The argument can also be formulated by juxtapose disobedience and civility within the concept of citizen virtue. For example, one may ask: Is non-cooperation, non-compliance, or overt defiance of a government policy or law an act of virtue or vice of a citizen? How is civility as one of the citizen virtue be reconcile with act of breaking the law within the conception civil obedience? 2. Conceptions of civil disobedience: a. John Rawls’s conception: “I shall begin by defining civil disobedience as a public, nonviolent, conscientious yet political act contrary to law done with the aim of bringing about change in the lawn or policies of the government. By acting in this way one addresses the sense of justice of the majority of the community and declares that, in one’s considered opinion the principles of social cooperation among free and equal men are not being respect. …It allows for what some have called indirect as well as direct civil disobedience.” (Ralws, 1971, P. 365-366) b. Jurgen Habermas’s conception: In an interview made in 1986, Habermas said, “There are three things to be said about that (referring to civil disobedience). First: civil disobedience cannot be ground in an arbitrary private Weltanschauung. But only in principles, which are anchored in the constitution itself. Second: civil disobedience is distinguished from revolutionary praxis, or from a revolt, precisely by the fact that it explicitly renounces violence. The exclusively symbolic breaking of rules ― which furthermore is only a last resort, when all other possibilities have been exhausted ― is only particularly urgent appeal to the capacity and W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 8 willingness for insight of the majority. Third: a position, such as that defended by Hobbes, Carl Schmitt, or …. In which the upholding of the law is made only the highest, but the exclusive ground of legitimation of a legal system, seems to me to be extremely problematic, After all, one would very much like to know under what conditions, and for what purpose, the legal peace should be upheld.” (Habermas, 1986, P. 225) c. Ronald Dworkin’s conception: “Civil disobedience…is very different from ordinary criminal activity motivated by selfishness or anger or cruelty or madness. It is also different…from the civil war that break out within a territory when one group challenges the legitimacy of the government or the dimensions of the political community. Civil disobedience involves those who do not challenge authority in so fundamental a way. They do not think of themselves…as seeking any basic rupture or constitutional reorganization. They accept the fundamental legitimacy of both government and community; they act to acquit rather than to challenge their duty as citizens.: (Dworkin, 1985, P105) d. Jean Cohen and Andrew Arato’s conception: “Civil disobedience involves illegal acts, usually on the part of collective actors, that are public, principle, and symbolic in character, involve primarily nonviolent means of protest, and appeal to the capacity for reason and the sense of justice of the populace. The aim of civil disobedience is to persuade public opinion in civil and political society…that a particular law or policy is illegitimate and a change is warranted. Collective actors involved in civil disobedience invoke the utopian principles of constitutional democracies appealing to the ideas of fundamental rights or democratic legitimacy.” (Cohen & Arato, 1992; quoted in Habermas, 1996, P. 383) 3. Justificatory grounds for Civil Disobedience a. The institutional assumption of civil disobedience: As the preceding definitions suggest, advocates and organizers of civil disobedience start off their campaign under the working assumption that they are living “within a more or less just democratic state and that they “recognize and accept the legitimacy of the constitution” (Rawls, 1971, P. 362) And their focal point of defiance is only on particular law or policy, which they find so unacceptable or even wrong that they have to defy it directly or indirectly. As a result, the organizers and participants of a civil disobedience campaign owe the law-abiding majority of the community a burden of proof of their act of disobedience. b. Ronald Dworkin, a prominent scholar of jurisprudence in the US, has induced three basic justificatory grounds for civil disobedience. i. “Conscience or integrity-based” civil disobedience: He points to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 in the US. He indicates, “Someone who believes it would be deeply wrong to deny help to an escaped slave who knocks at his door, and even worse to turn him over to the authority, think the Fugitive Slave Act requires him to behave in an immoral way. His personal integrity, his conscience, forbids him to obey.” (Dworkin, 1985, P. 107) ii. “Justice-based” civil disobedience: Dworkin points to the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam-war movement in the US during the 1960s in the US. He suggests that those participating in these civil disobedient movements aim “to oppose and reverse a program they believe unjust, a program of oppression by the majority of a minority. W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 9 Those in the civil rights movement who broke the law and many civilians who broke it protesting the war in Vietnam thought the majority was pursuing its own interests and goals unjustly because in disregard of the rights of others, the rights of the domestic minority in the case of civil rights movement and of another nation in the case of the war. This is “just-based” civil disobedience. (Dworkin, 1985, P. 107) iii. “Policy-based” civil disobedience: Dworkin points to the movement of occupying US military bases in West Germany during the Euro-missile deployment debate in the 1980s. He suggests that “people sometimes break the law not because they believe the program they oppose is immoral or unjust…but because they believe it very unwise, stupid, and dangerous for the majority as well as the minority. The recent protest against the deployment of American missiles in Europe, so far as they violate local law, were for the most part occasions of this third kind of civil disobedience , which I shall call ‘policy-based’. If we tried to reconstruct the beliefs and attitudes of …the people who occupied the military bases in Germany, we would find that…they thought that majority had made a tragically wrong choice from the common standpoint. …They aim, not to force the majority to keep faith with principle of justice, but simply to come to its sense.” (Dworkin, 1985, P. 107) 4. The function of civil disobedience in democratic and rule-of-law state: Taking together John Rawls’, Jurgen Habermas’ and Ronald Dworkin’s formulations, they consensually point to the positive contribution of civil obedience to the formation of the political culture of the democratic and rule-of-law state (Rechtsstaat in Germen) a. John Rawls underlines, “Indeed, civil disobedience ( and conscientious refusal as well) is one of the stabilizing devices of a constitutional system, although by definition an illegal one. Along with such things as free and regular elections and an independent judiciary empowered to interpret the constitution (not necessary written), civil disobedience used with due restraint and sound judgment helps to maintain and strengthen just institutions. By resisting injustice within the limits of fidelity to law, it serves to inhibit departures from justice and to correct them when they occur. A general disposition to engage in justified civil disobedience introduces stability into a well-ordered society, or one that is nearly just.” (Rawls, 1971, P. 383) b. Jurgen Habermas characterized the civil disobedience (in the form of occupying the US military bases in Germany) against the Euro-missile deployment in Germany in early 1980 in the following ways: “The present movement gives us the first chance, even in Germany, to grasp civil disobedience as an element of a ripe political culture.” (Habermas, 1983; quoted in Specter, 2010, P. 156; my emphasis) “The practice gives the German public, for the first time, the chance to liberate itself from a paralyzing trauma and to look without fear on the previous taboo question of the formation of a radical democratic consciousness. The danger is that this chance ― which other countries with a longer democratic tradition …have integrated productively ― will be passed up.” (Habermas, 1985; quoted in Specter, 2010, P. 156; original emphasis) W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 10 c. Jurgen Habermas has also put civil disobedience against the context of Rechtsstaat (the rule-of-law state) and suggests that “The paradox of the Rechsstaat is that it must embody positive law, but also stand for principles which transcend it, and by which positive law may be judged. The Rechsstaat, wanting to remain identical with itself, stands before a paradoxical task. It must protect …against injustice that may emerge in legal forms, although this mistrust cannot take an institutionally secured form. With this idea of a non-institutionalizable mistrust of itself, the Rechsstaat projects itself over the entirety of its positive law.” (Habermas, 1983; quoted in Specter, 2010, P. 156) Immediately following the quotation, Mathew Specter underlines that “Habermas claim that the paradox can be resolved by citizens of ‘matured’ political culture because they alone show the ‘sense of judgment’ necessary to decide how to act in relation to unjust laws, or majority decision, with which they agree. Civil disobedience was thereby figured as a necessary component of a successful Rechsstaat.” (Specter, 2010, P. 167; my emphasis) d. Ronald Dworkin in retrospective reflection on the civil disobedient movements of the US in the 1960s and 70s, he suggests that “we can say something now we could not have said three decades ago: that Americans accept that civil disobedience ha s a legitimate if informal place in the political culture of their community. Few Americans now either deplore or regret the civil rights and antiwar movements of the 1960s. People in the center as well as on the left of politics give the most famous occasions of civil disobedience a good press, at least in retrospect. They concede that these acts did engage the collective moral sense of the community. Civil disobedience is no longer a frightening idea in the United States.” (Dworkin, 1985, P. 105) 5. To summarize, we may map out the connection between the rule of law, democratic political participation and civil disobedience in the following way W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 11 (II) Nationality Membership in Modern Political Communities (ii) A. Nationality: It refers to the sense of comradeship of being the member of the political community known as the modern nation. 1. The conception of the nation a. Max Weber’s conception of the nation: “If the concept of ‘nation’ can in any way be defined unambiguously, it certainly cannot be stated in terms of empirical qualities common to those who count as members of the nation. In the sense of those using the term at a given time, the concept undoubtedly means, above all, that one may exact from certain group of men a specific sentiment of solidarity in the face of other groups. Thus, the concept (of nation) belongs in the sphere of values. Yet, there is no agreement on how these groups should be delimited or about what concreted action should result from such solidarity.” (Weber, 1948, p.172) b. Anthony Smith’s definition of the nation: Smith has defined that “the nation was a group with seven features: 1. cultural differentiae (i.e. the ‘similarity-dissimilarity’ pattern, members are alike in the respects in which they differ from non-members) 2. territorial contiguity with free mobility throughout 3. a relatively large scale ( and population) 4. external political relations of conflict and alliance with similar group 5. considerable group sentiment and loyalty 6. direct membership with equal citizenship rights 7. vertical economic integration around a common system of labour.” (Smith, 1983, p. 186; original numbering c. David Miller’s conception of the nation: Miller’s defines the nation as “a community (1) constituted by shared belief and mutual commitment, (2) extended in history, (3) active in character, (4) connected to a particular territory, and (5) marked off from other communities by its distinct public culture.” (Miller, 1995, P.27) 2. The conception of nationality: Nationality refers to the disposition, intentionality and capacity that members of a nation are expected to embodied. Miller furthers his formulation that “the idea of nationality which I take to encompass the following three interconnected propositions.” (Miller, 1995, P.10) i. National identity: It refers to that individuals have developed and continuously possess a sense of belonging to definite national communities, which they believe “really exist” (Miller, 1995, P. 10). Furthermore, members of a national community also hold that their national identity is an essential part, if not most essential part, of their personal identity. This proposition claims that “identifying with a nation, feeling yourself inextricably part of it, is a legitimate way of understanding your place in the world.” (Miller, 1995, P. 11) ii. Ethical obligations: Nationality implies a “claims that nations are ethical communities. They are contour lines in the ethical landscape. The duties we owe to our fellow-nationals are different from, and more extensive than, the duties we owe to human beings as such.” (Miller, 1995, P. 11) These national ethical duties may further be juxtaposed with one’s duties family, religious group, or other human associations. These ethical obligatory W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 12 claims also imply restrictions that they only apply within definite national boundaries, “and that in particular thee is no objection in principle to institutional schemes ―such as welfare states― that are designed to deliver benefits exclusively to those who fall within the same boundaries as ourselves.” (Miller, 1995, P. 11) iii. Political self-determination: “The third proposition is political, and states that people who form a national community in a particular territory have a good claim to political self-determination; there ought to be put in place an institutional structure that enables them to decide collectively matters that concern primarily their own community. Notice that …I have phrased this cautiously, and have not asserted that the institution must be that of a sovereign state. …Nevertheless national self-determination can be realized in other ways, and as we shall see there are cases where it must be realized other than through sovereign state, precisely to meet the equally good claims of other nationalities.” (Miller, 1995, P. 11) 3. Perspectives in National Identity Study In light of studies in nationalism and national identity generated since the second half of the 20th century, two sets of dichotomous perspectives could be synthesized. a. In relation to the nature of the concept of national identity, there seems to be two dichotomous theoretical stances prevailing i. Essentialism: Essentialism approaches national identity as essentials or attributes, which are naturally endowed or structurally determined. This perspective takes national identity as well as gender identity or class identity as given facts and preexisting reality. Hence, the formations of national identities are conditioned, shaped, or determined by sets of essentially fixed traits, such as biological consanguinity, racial origins, place of birth, cultural and linguistic heritage, etc. ii. Constructionism: Constructionism approaches national identity as socially constructed reality, which are negotiable and maneuverable. They are on the one hand collectively constituted in social process or even social movement, such as national liberation movement, and individually constructed in deliberately presentations and articulations. b. In relation to the origins of the national identity, there are two adversary perspectives, namely “primordialism” and “modernism”. i. Primordialism: It attributes the origin and/or the contributing factors to national-identity formation to some “primordial ties” inherited from the ancient past, such as sense of kinship; feeling of consanguinity; earth boundedness and geographical embeddedness. ii. Modernism: It attributes the rise of nationalism and the formation of national identity to their instrumental and functional contributions to modernization and more specifically industrialism. It emphasizes the contribution of national identity to the formation of a common ground for the secular and anonymous lifestyle of factory production, market exchange, urbanism, democratic participation, etc. W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 13 Modernism Essentialism Constructionism Primordialism B. Development of the Modern Form of Political Community: Nation-State 1. The paradoxical natures of the nation-state: Throughout the developing trajectories of the nation-states, their two constituent sites, namely the state and nation, have been in paradoxical relationship in most of the time. The paradox is primarily espoused by the different institutional natures of the two human aggregates. a. For the state, it is a human organization formed primarily by naked physical forces and then institutionalized by political and legal authorities, desirably in the form of constitutional-liberal democracy. It demands its human subjects complete compliances and imposes sovereign and non-disputable power over its territory b. For the nation, it is a human community formed by a “specific sentiment of solidarity”. This psycho-cultural sense of solidarity and “we-group feeling” may take on various forms and shapes in different historical and socio-political contexts. They have unleashed tremendous collective human efforts in accomplishing epical movements in the forms of independent movements or national liberations or in waging devastating wars in the forms of ethnic cleansings or genocides. 2. Empirical contexts of the nation-state formations: a. “The distinction between states and nations is fundamental… States can exist without a nation, or with several nations, among their subjects; and a nation can be coterminous with the population of one state, or be included together with other nations with one state, or be divided between several states. The belief that every state is a nation, or that all sovereign states are national states, has done much to obfuscate human understanding of political realities. A state is a legal and political organization, with the power to require obedience and loyalty from its citizens. A nation is a community of people, whose members are bound together by a sense of solidarty, a common culture, a national consciousness. Yet in the common usage of English and of other modern languages these two distinct relationship are frequently confused.” (Seton-Watson, 1977, P. 1) b. “According to recent estimates, the world’s 184 indendent states contain over 600 living language groups, and 5,000 ethnic groups. In very few countries can citizens be said to share the same language, or belong to the same ethnonational group.” (Kymlicka, 1995, P. 1) W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 14 3. The Historical Trajectories of Nation Building a. The first generation of nation building in Western Europe and American in 18th -19 centuries i. Nation-building through revolution and constitution of the republics - The French Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen proclaims that “the source of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation; no group, no individual may exercise authority not emanating expressly therefore.” (quoted in Connor, 1994, p. 39) - The Constitution of the United States writes, “We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessing of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this constitution for the United State of America.” ii. Nation-building through the sentiment of imperial power and prestige of the Empire in Britain iii. Independent revolutions and constitution of republics among Creole in South American in the 18th century iv. Nation-formation through unification of multiple sovereign states in Germany and Italy in the 19th century b. The second generation of nation building in Eastern Europe in the first half of the 20th century i. Scattered national fragments in Eastern Europe, especial in Balkan peninsula, as the results of wars between imperial powers of the East and the West, and between Christianity and Muslim ii. Nation-building project under the ruling of authoritarian socialist party-states after WWII under the patronage of the Soviet Union. c. The third generation of nation building in Asia and Africa in the second half of the 20th century i. Independent movements in European colonies after WWII ii. Nation building took the form of ‘state-based territorialism’ (Smith, 1983) iii. Separatism in independent states of former colonies, e.g. India continent and Malaysia peninsula d. The dissolution of the Soviet Union and East-European socialist bloc after 1990s. i. Formations of nation-states of former Soviet publics ii. Dissolution of former East-European socialist states into ethnic-states and unleashed bloody ethnic wars and genocides 4. The Project of Nation Building in China a. From empire-based territorialism to hereditary nationalism i. Imperialist invasion to the Ching Empire: The birth of national awareness ii. The nationalist revolution and the separatism of the warlords b. From hereditary nationalism to acquired nationalism i. The Japanese invasion and the united front of the Nationalist and Communist parties ii. The establishment of the People Republic of China in 1949: The constitution of the sovereign state of multiple nations iii. The economic liberalization of PRC in 1978 and the emergence of the “context of pluralistic unity”多元一體格局 iv. The Students movement in 1989 v. Olympic game and ethnic disturbance in Tibet in 2008 W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 15 vii.Ethnic disturbance in Xinjiang in July 2009… 5. The constitution of the national identity for subjects of the HKSAR: Controversies over the Moral and National Education: Curriculum Guide (Primary 1 to Secondary 6) C. Is Patriotism a Virtue or a Vice? A Value and Moral Enquiry 1. Meaning of patriotism: a. Alasdair MacIntyre’s definition: In his oft-cited article entitled “Is Patriotism a Virtue?” MacIntyre defines patriotism as “a kind of loyalty to a particular nation which only those possessing that particular nationality can exhibit. Only Frenchmen can be patriotic about France.” (MacIntyre, 2002, P. 44) Furthermore, MacIntyre characterizes that patriotism as a kind of attitude supportive towards one’s own nation and evaluative of its merits and achievements are extremely particularistic in nature. That is, “patriots does not value in the same way precisely similar merits and achievements when they are the merits and achievements when they are the merits and achievements of some nation other than his or hers. For he or she ── at least in the role of patriot ── values them not justice as merits and achievements, but as the merits and achievements this particular nation.” (MacIntyre, 2002, P. 44) b. Leo Tolstoy’s definition of “extreme patriotism”: Tolstoy states that “The sentiment (of patriotioism), in its simplest definition, is merely the preference of one’s own country or nation above the country or nation of any one else.” (Tolsky, 1969, quoted in Nathanson, 1993, P. 4) He goes on to emphasized that patriotism may consist the following features. “1. A belief in the superiorty of one’s country 2. A desire for dominance over other contries 3. An exclusive concern for one one’s own country 4. No constrints on the pursuit of one’s country’s goals 5. Automatic support of one’s country’s military policies.” (quoted in Nathanson, 1993, P. 29) It must be underlined that Tolstoy did not himself identify with such a extreme version patriotism. In fact, he formulates it for criticism and he goes on to state that “this sentiment is …very stupid and immoral.” c. Stephen Nathanson’s definition of “moderate patriotism”: He stipulates that patriotism need not have the features that Tolstoy attributes and thus that it need not be open to his criticisms. Moderate patriotism involves the following features: 1. Special affection for one’s country 2. A desire that one’s country prosper and flourish 3. Special but not exclusive concern for one’s own country 4. Support for morally constrained pursuit of national goals 5. Conditional support of one’s country’s policies.” (Nathanson, 1993, P. 34) 2. Criticism of patriotism from the deontological and liberal perspectives in value and morality enquiry a. According to the deontological perspective in morality enquiry, all evaluation and moral judgments are supposed to be judged according to some impersonal and impartial criteria or rules. However, for patriotism it “requires me to exhibit peculiar devotion to my nation and you to yours. It requires me to regard such contingent social facts as where I was born and what government ruled over that place at that time, who my parents were, who W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 16 my great-great- grandfathers were, and so on, as deciding for me the question of what virtuous action is.” (MacIntyre, 2002, P. 45) Accordingly, the deontological “moral standpoint and the patriotic standpoint are systematically incompatible.” (MacIntyre, 2002, P. 45) b. Furthermore, according to the liberal perspective in moral enquiry, the criteria and rules, which moral judgments should follow, should not only be impartial and impersonal but should also i. be “neutral between rival and competing interests;” ii. be “neutral between rival and competing sets of beliefs about what the best way for human beings to live is;” iii. take individual human being as the basic unit in moral evaluations and “each individual is to count for one and nobody for more than one;” and iv. apply to all moral agents universally “independent of all particularity.” (MacIntyre, 2002, P. 47) Accordingly, it is obvious that patriotic standpoint of morality, which base its judgment on the particularistic interest and form of life and belief of one own nation, will not be incompatible with that of the liberal but will simply be treated a vice. 3. In search of morally justifiable or virtuous ground for patriotism a. MacIntyre indicates first of all that “For patriotism and all other such particular loyalty can be restricted in their scope so that their exercise is always within the confine imposed by morality. Patriotism need be regards as nothing more than a perfectly proper devotion to one’s own nation which must never be allowed to violate the constraints set by the impersonal moral standpoint.” (MacIntyre, 2002, P. 46) b. As a communitarian, MacIntyre is quick to stress that there “is never morality as such, but always the highly specific morality of some highly specific social order.” (P. 48) And “it is an essential characteristic of the morality which each of us acquires that is learned from, in and through the way of life of some particular community.” (P. 48) MacIntyre further specifies that the distinct rules of morality derived from the way of life of a particular community are therefore (P. 48) i. specific “practices” and responses to the natural and social situations in which a community found and formed itself; ii. specific “narratives” through which a community and its way of life evolve and develop through its own history iii. specific “tradition” and social arrangements and orders which have been institutionalized in the way of life of a community c. Built on this communitarian version of moral rules, MacIntyre further rejoin the liberal’s version of free-footing (impartial and neutral) moral agents by specifying that i. the moral goods pursued by moral agents are always embedded in “the enjoyment of one particular kind of social life, lived out through a particular set of social relationships.” (P. 49) Therefore, “rules of certain kind are justified by being productive of and constituted of goods of a certain kind …only if …these particular sets of rule incarnated in the practices of …these particular communities are productive or constitutive of ….these particular goods enjoyed at certain particular times and places by certain specifiable individuals.” (P. 49) ii. a moral duty and agency performed by a moral agent “is characteristically and generally a hard task for human being.” MacIntyre W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 17 underlines that “I can only be a moral agent because we are moral agents, that I need those around me to reinforce my moral strengths and assist in remedying my moral weakness. It is general only within a community that individuals become capable of morality.” (P. 49) d. Taken together, MacIntyre asserts that patriotism can be accepted as a virtue on conditions that i. “If first of all it is the case that I can only apprehend the rules of morality in the version in which they are incarnated in some specific community; ii. “if secondly it is the case that the justification of morality must be in terms of particular goods enjoyed within the life of particular communities; iii. “if thirdly it is the case that I am characteristically brought into being and maintained as a moral agent only through the particular kinds of moral sustenance afforded by my community, then it is clear that deprived of this community, I am unlikely to flourish as a moral agent.” (P. 50) 4. Dialectics between liberalism and communitarianism in the controversy over patriotism a. Confronted with the two rival and incompatible moralities, namely morality of liberalism and that of patriotism, MacIntyre suggests that “one way to begin is to be learned from Aristotle, …we shall do well to proceed dialectically.” (P. 50) b. One the one hand, from the viewpoint of the morality of liberalism, patriotism is “a permanent source of moral danger.” (P. 54) It is because the morality of patriotism will always argue for exemption from general of morality principles in the interest or even common goods for one’s own nation. MacIntyre agrees that such accusation from the liberals “cannot in fact be successfully rebutted” by the patriots. (P. 54) Therefore, MacIntyre suggests that morality of patriotism must be extremely careful in examining their arguments and justification for exemption from moral principles for the sake of national goods. MacIntyre specifically underlines that “whatever is exempted from the patriot’s criticism the status quo of power and government and the policy pursued by those exercising power and government never need be so exempted. What then is exempted? The answer is: the nation conceived as a project, a project somehow or other brought to birth in the past and carried on so that a morally distinctive community was brought into being which embodied a claim to political autonomy in its various organized and institutionalized expressions.” However, such patriotic claim for the overall project of the nation can pose moral danger “to the best interest of mankind” as the case of the project of the Nazi Germany. (P. 52) Hence, the exemption is by no means absolute and must be critically examined dialectically and continuously. c. On the other hand, MacIntyre underlines once again that “liberal morality of impartiality and impersonality turns out also to be a morally dangerous phenomenon in an interesting corresponding way. For suppose the bonds od patriotism to be dissolved: would liberal morality liberality be able to provide anything adequately substantial in its place?” (P. 54) “A central contention of the morality of patriotism is that I will obliterate and lose a central dimension of the moral life if I do not understand the enacted narrative of my own individual life as embedded in the history of my country. For if do not so understand it I will not understand what I owe to other or what others owe to me.” (P. 55) As a result, each individuals will probably W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 18 come together simply for the pursue of naked self- interest and competition for maximization of one’s own profit like the institution of the capitalist market or simply for pleasure seeking and instant gratification to mass media and mass consumption markets. In the end, the morality of liberalism will be relegated into morality of emotionism as MacIntyre criticizes at the beginning of After Virtue. (2007) Additional References Barber, Benjamin R. (1999) “The Discourse of Civility.” PP. 39-47. IN S.L. Elkin and K.E. Soltan (Eds.) Citizen Competence and Democratic Institutions. Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press. Bendix, Reinhard (1977) Nation-Building and Citizenship. Berkeley: University of California Press. Cohen,, Jean and Andrew Arato (1992) Civil Society and Political Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Dworkin, Ronal (1977) “Civil Disobedience.” PP. 206-222. In R. Dworkin. Taking Rights Seriously. London: Duckworth. Dworkin, Ronald (1984) “Rights as Trumps.” PP. 153-167. In J. Waldron (Ed.) Theories of Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dworkin, Donald (1985) “Political Judges and the Rule of Law.” Pp. 9-32. In R. Dworkin. A Matter of Principle. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Dworkin, Ronald (1985) “Civil Disobedience and Nuclear Protest.” Pp. 104-116. Ronald Dworkin. A Matter of Principle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Galston, William A. (1991) Liberal Purposes: Goods, Virtues, and Diversity in the Liberal State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gutmann, Amy and D. Thompson (2004) Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton: Princeton University Press. Habermas, Jurgen (1986) Autonomy and Solidarity: Interviews with Jurgen Habermas, Revised Edition. Edited by P. Dews. London: Verso. Habermas, Jurgen (1996) Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. MacIntyre, Alasdair (2002) “Is Patriotism a Virture.” PP. 43-58. In I. Primoratz (Ed.) Patriotism. New York: Humanity Books. Macpherson, C.B. (1997) The life and Times of Liberal Democracy. Oxfard: Oxford University Press.Janoski, Thomas (1998) Citizenship and Civil Society: A Framework of Rights and Obligations in Liberal, Traditional, and Social Democratic Regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Marshall, T.H. (1992) “Citizenship and Social Class.” Pp. 3-51. T.H. Marshall and T.B. Botoomore. Citizenship and Social Class. Lonon: Pluto Press. Kymlicka, Will. (2003). Multicultural Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press. W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 19 Nathanson, Stephen (1993) Patriotism, Morality, and Peace. Lanham: Rowan & Littlefield. Specter, Andrew G. (2010) Habermas: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seton-Watson,Hugh. (1977). Nations and States: An Enquiry into the Origins of Nations and the Politics of Nationalism. Boulder: Westview Press. Walzer, Michael (1970) Obligations: Essays on Disobedience, War, and Citizenship. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. W.K. Tsang The Good Society and its Learnt Citizens 20