Asthma Patient Passport - LNNM - Florence Nightingale Foundation

advertisement

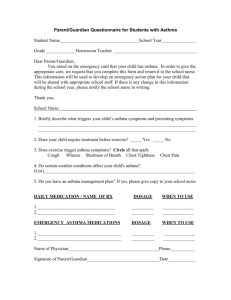

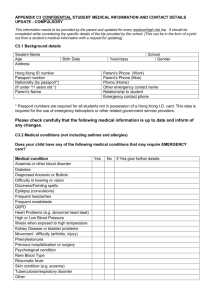

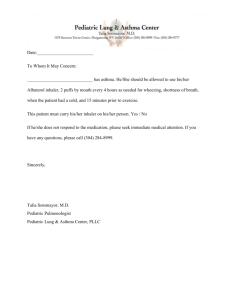

Report prepared for The London Network for Nurse and Midwives/ The Florence Nightingale Foundation Partnership- 31st May 2013 The Asthma Patient Passport Karen Newell (Respiratory Nurse Specialist) Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust 1 Contents p. 3 p. 4 p. 5-6 p. 7 p. 8 p. 9 p. 10 p. 11 p. 12 p. 13 p. 14 p. 15 p. 16 p. 17 p. 18 p. 19 p. 20 p. 21 p. 22 p. 23 p. 24 p. 25-27 p. 28-35 p. 37-38 p. 39 p. 40 p. 41 Abstract Background/ local context The Process Maps, The concept of an Asthma Patient Passport, Consultation with the stakeholders The Plan, Aims and Objectives Saving Lives, the patient experience, the clinician feedback, finance and design and printing. Prototype Asthma Patient Passport- version 2 Testing, testing, testing- version 3 Consultation and clinical governance and approvals process Version 4- clinical governance approval process The official Asthma Patient Passport Planning for after the evaluation and the learning The final version of the Asthma Patient Passport The results, selection of answers for The Near Time Patient Experience Questionnaires of particular relevance Discussion- timeliness of treatment Results Results Case study demonstrating the benefits of the Asthma Patient Passport, Positive clinician feedback Evaluation, Saving Lives Improving the patient experience, Making it easier for healthcare professionals/ staff The learning Summary, Dissemination Appendix 1- Version 1 of the Asthma Patient Passport Appendix 2- The Near Time Patient Experience Questionnaire Appendix 3- The College of Emergency Medicine Standards for Asthma Appendix 4- Management of Acute Severe Asthma in Adults in A&E (BTS, 2012) Appendix 5- Asthma Steps (BTS, 2012) References 2 Abstract The following report outlines the development, testing and the evaluation of the Asthma Patient Passport (APP). The APP was specifically created with the ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’ patients in mind and is an invention born of necessity. This is because this group of patients do not access emergency services when they need to and therefore put their lives at risk. They prefer to stay at home and use high dose bronchodilator therapy rather than feel out of control and vulnerable in the Emergency Department (ED). This is dangerous behaviour because if treatment needs to be escalated they are not in the right place. Patient passports had been used in other groups of patients and following a group discussion, it was felt that a bespoke APP may encourage the patients to access care appropriately. It was obviously important to involve all stakeholders and this not only informed but drove the process, so that a product that blended the requirements of patients, health professionals and ED receptionists was created. Over the period of a year, the APP was used and refined so that there is now a useable and helpful document that not only gives this patient group the confidence to go to ED when they need to, but also helps the staff. With the support of the LNNM/Florence Nightingale Foundation Partnership and following the model for improvement, the APP was tried and tested. The aims were to: save lives, improve the patient experience and help the clinicians. The APP was rigorously evaluated by a variety of different methods including; a validated patient questionnaire, a respected ED audit tool, the undertaking of a case-study and patient and clinician feedback. The APP achieved all of its original aims and found that it facilitated the patient being treated at the right time, with the right treatment, in the right place- this is the learning. The project group is ready to disseminate and spread the learning nationally. This will be done by publishing the good news in a peer review journal and by continuing to work closely with the London Ambulance Service and Asthma UK. The Severe Asthma Nurses Network has also registered an interest. Shared wider the APP could help save lives and improve the experience of thousands of people with asthma and help clinicians. 3 Background Approximately 1,200 people with asthma die in the UK each year and 90% of these deaths are preventable. The UK has a higher death rate from asthma than other similar countries and numbers have not reduced significantly in recent years (Asthma UK). There is currently a strong focus on asthma deaths, Asthma UK is running the Stop Asthma Deaths campaign and as of the 1st February 2012, the National Register of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) was convened in an attempt to understand the circumstances surrounding asthma mortality. So far, the NRAD are investigating approximately 120 asthma deaths per month. The NRAD aims to identify avoidable factors and make recommendations for implementing changes to improve care and to reduce the number of deaths from asthma in the future. Small scale local studies have previously found that there are 3 main reasons why ‘avoidable’ asthma deaths occur and these are; patients’ failure to recognise the severity of the asthma attack, failure of healthcare professionals to recognise the severity of the attack and inappropriate or under treatment. Local context In conjunction with NHS Improvement, we had recently undertaken some work around asthma re-attendance in the Emergency Department (ED) at Guy’s and St.Thomas’ Hospital (GSTT). The project had been a great success and 30 day asthma re-attendance decreased by 45% and admissions by 60%. Reducing asthma re/attendance and admissions is an indicator of better asthma control and quality of life. The ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’ patients were excluded from the scope of the NHS Improvement work because it was felt that they had different needs. Our ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’ patients are fully medically optimised and have the ongoing support of the specialist asthma clinic. They all have a bespoke asthma action plan, which is drawn up between themselves and the Asthma Nurse Specialist. The plan outlines how to titrate asthma treatments according to symptoms and there are explicit statements about when to access the GP/Practice Nurse and when to seek emergency medical help. It is my privilege to work with the ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’ patients and I spend a lot of time working out action plans with them- it is one of the most important parts of my role. After a while I began to realise that whilst the patients were delighted to have a plan to help them take better control of their asthma, there was usually awkwardness around when and how to access emergency medical care. On exploring this I realised that the patients were actually putting their lives at risk because they had such a difficult time in ED, they preferred to stay at home and take high doses of bronchodilator therapy. There is a gamut of reasons why they avoid the Emergency Department: they feel vulnerable they are afraid to use ED when they are least able to talk they are unable to say what they need they are asked the same questions many times they feel that they are not always listened to treatment isn’t always escalated as quickly as it needs to be. Another obstacle was that they had no choice as to which ED the ambulance service took them and they would therefore elect to use either their own or public transport 4 which is a dangerous thing to do. It was agreed that this was less than ideal and that something had to be done about it. The Process Map The core group was four patients with ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’, the Allergy CNS and the Asthma CNS. The patient journey from the front door via ED was process mapped in an attempt to get a better understanding of what it is was that happens in ED that made the experience so difficult. Doing the process map highlighted how complicated and how difficult the system is for patients. What was clearly evident is how many times the patients were asked questions and also how many times they were left alone, this at a time when they must be very breathless and very scared. The mapping process also provided the opportunity for the patients to get together and talk about their shared experience and along with the CNSs, to create a culture of ownership, responsibility and accountability for improving the process. The end product - the process maps- were highly visual and easy to understand. They use the language of the patients. Asthma Patients’ Pathway through A&E via Ambulance (Blue Lighted) Call 999 Questions to assess from LAS Paramedics arriveobservations, one nebuliser Questions to assess Observations Treatment Treatment on site Moved into ambulance More observations and background questions Doctor reviews patient Another nebuliser enroute A&E- paramedics handover to nurse Questions Questions Re-assessment questions Waiting for medic Medics arrive Alone asks questions Alone Ward or home 5 Asthma Patients’ Pathway through A&E self presenting, without APP Reception Sit and Wait Questions Alone Observations/PEF Instructs nurse to give one Salbutamol Sit and Wait Observations Alone Doctor Admit Patient Observation Ward / Home Seen by Medics Questions Called by Triage Nurse Observations, PEF(?) Questions Called by Doctor and escorted to cubicle Questions Sit and Wait Alone Nebuliser including Atrovent Treatment Observations/PEF Questions Decide whether nebuliser needed and further treatment Seen by Doctor The concept of an Asthma Patient Passport It is important to point out that this particular group of patients aren’t necessarily local to GSTT and therefore need to use different EDs and so a local arrangement wasn’t an obvious solution. One idea was to have a national database of all those people with ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’ so that the ambulance service and the various UK EDs had all the necessary information about the patient. This would help the asthma patients feel less vulnerable and also obviate the need to constantly answer questions when they are at a point when they are so breathless that they can’t actually talk. Whilst all thought this was a good idea it was realised that this was something for the future, and what was needed was something for now, so that the patients were not at such high risk. It was known that other long-term condition groups, such as people with learning difficulties and people with mental health problems, were already using a Patient Passport and that this had been found to be helpful. There was also a local COPD Passport being used and it was felt that the design of the COPD Passport was a good one. The COPD Passport is a credit card sized z-card and is a simple record of relevant demographic and clinical information. Where the Asthma Patient Passport would excel is that it would be designed by patients for patients and would also take into account both the needs of LAS and the various EDs. The other important factor was the decision to use the model for improvement which is a tried and tested way for implementing change in health services. The same approach had been employed in NHS Improvement work and had demonstrated itself to be valuable as a way of winning commitment from various health staff groups and of course the patients themselves. Consultation with the stakeholders Following the meeting with the patients, various stakeholders were asked for their opinions regarding the APP idea including the ED consultants, the ED nurses, ED reception staff manager and the Asthma Professor. All thought it was a good idea. LAS stated that it could be “very helpful in information gathering and also for when 6 the asthma patient presents without a wheeze”. The Communications department said that it was a “simple but effective idea” and suggested a pilot so as “to get a design that is patient friendly and which also takes into account the clinical perspective and to marry the two”. They went on to advise about creating a mock up of an APP, running a trial and then onto discussions with the design and print companies. See appendix 1 for first version. The Plan The PDSA cycle was used to support the model for improvement in the National Improvement work- this was applied in the APP work. We are now on version 9 of the APP. PDSA means: PLAN: DO: STUDY: agree the change to be tested or implemented carry out the test or change and measure the impact study the data before and after the change and reflect on what was learnt plan the next change cycle (amending the original idea if it was not successful) or plan implementation of successful ideas ACT: The aim was to test first the APP on a really small scale and evaluate. The objectives were that the APP should facilitate: Saving Lives Improving the patient experience Making it easier for healthcare professionals/ staff Another anticipated benefit was that patients and healthcare staff would work together in partnership and to enhance good 2-way communication. If the APP was found to be effective, the learning would be spread. Trialing protol type version 4 Pull CAS cards (nov'11 to May '12) Analyse CAS cards A&E input - clinicians reception A&E awareness raising - 5 minute slide Data gathering Launch version 5 Patient Questionnaire Clinician Questionnaire 7 n13 Ju -1 3 Ma y r-1 3 Ap -1 3 Ma r b13 Fe n13 Ja 12 De c- 12 No v- Oc t-1 2 2 Se p1 2 2 g1 Au l- 1 Ju n12 Ju -1 2 Ma y r-1 2 Ap -1 2 Ma r b12 Fe Ja n12 The Project Plan ‘Saving lives’ would be captured by the action of patients seeking help appropriately. The patients would report back. The patient experience would be measured by: The Near Time Experience Patient Questionnaire- see appendix 2 The College of Emergency Medicine audit tool which measures ‘timeliness of treatment’- see appendix 3. Patient feedback The Patient Experience Team at GSTT advised that the aforementioned questionnaire would be a reasonable way of analysing the patient’s journey through ED. It was a well constructed tool, was easy to use and employed a couple of CQUIN questions as well. The patients would be asked to complete the questionnaire every time they used the APP and the results would be collated at the end. The fact that the patients used different EDs was something that needed to be worked with and it may be useful to see how the APP is received in different EDs, especially those that aren’t GSTT ED, as the climate at GSTT ED was known to be receptive to improvements in asthma care. The hope also was that the results could also be compared with the experience of other patients that have used GSTT ED throughout the same period, so that this was looked at within the wider context of being a patient in GSTT ED. The College of Emergency Medicine audit tool would go some way to measuring how quickly the patient is seen as a measure of best practice. Data was extracted from the ED cards using Symphony which is an ED database. Looking at the ED cards would provide insight into what happened and when. Success was to be measured by using a control group and a study group. The control group was those adult patients with asthma that had used GSTT ED between 7th November 2011 and March 4th 2012. An Asthma Proforma had been introduced as part of the NHS Improvement work on the 7th November 2011 and it was more than likely that this in itself would improve timeliness of treatment. I needed to have the report written by the 1st June 2013 and I knew that there would need to be a decent amount of time to have the data analysed and to pull the report together. So, where I had hoped to compare two sets of six months of data, I realised that four months was more realistic- hence the 4th March cut off point. Thus, the 7th November 2011- 4th March 2012 was compared with the 5th November 2012- March 3rd 2013. It was also hoped that matching season for season would make the analysis as pure as possible. Finally, it was also important to note the uptake of the Asthma Proforma because if it had improved or declined from the first data collection period to the second this could have an effect on the validity of the results. The clinician evaluation would be attained by an evaluation section on the APP and by asking for verbal feedback. Finance and design and printing The finance side of things was inextricably connected with the design and printing and it wasn’t until November that the APP was printed and ready for use. Running parallel to this was the testing of the first prototypes, the consultation process and the clinical governance approval process. Every time the patients used the APP we learnt something new and this informed the design- as per PDSA- see below for early prototype. 8 Prototype Asthma Action Plan- version 2 9 Testing. testing, testing By the end June 2012 the above APP had been used a total of 13 times in 2 different hospitals. Initial feedback was that LAS were very complimentary and ED clinical staff had been generally impressed. The asthma patients reported that they are more likely to go to A&E and felt safer there when they have the APP. The ideas were beginning to come together and as per PDSA, with the next version of the APP: the emergency information is put at the beginning of the document the Asthma Specialist signature is added, which lends it credibility One of the patients asked a friend to do some design work. This was version 3. 10 The consultation process and clinical governance approvals process were inextricably connected and thus will be outlined simultaneously. The consultation process Between July 2012 and October 2012 ED clinical and non-clinical staff and LAS were extensively consulted. They made various suggestions and these were incorporated into the next design. Suggestions included: change the word ‘brittle’ to ‘severe’; having an explicit statement about what to do if arterial blood gases are needed; having a review date. The clinician evaluation was also built in. The stakeholders advised that they preferred the layout of version 3 but the content of version 4. The 2 were therefore blended as below as per version 5. Version 5 11 Clinical governance approval process Our colleagues in patient publications helped to fast track the APP through approvals so that by the end of October it was signed-off and sent off to the designers- see below. The approvals process involves gaining consensus from a whole range of people including pharmacists, patient publications. It was most helpful to have the full support of the ED lead at the approval stage. “We in A&E are very keen on this user friendly concept which should speed up patient care. We have had an opportunity to discuss the overall contents and are happy. The concept is no different than looking at an EPR letter with treatment recommendations but is more empowering for the patient as well as quicker access”. (ED consultant) 12 The official Asthma Patient Passport 13 Planning for after the evaluation and spreading the learning Ahead of the evaluation, the 6th December 2012 sees the British Thoracic Society Winter meeting and the opportunity is taken to introduce the idea of the APP and the project to the Severe Asthma Nurses Network (SANN). They suggest that it is presented at their meeting in September 2013. This is good publicity for the APP and maybe a possible spring-board to further testing in other UK areas. LAS are also interested in taking this further and make further suggestions to the design- see next page. These are incorporated into the final design at the end of the trial. Asthma UK continue to keep a firm interest in the project, especially as one of their current focuses is ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’, and ask a series of questions. 1. Did the use of the passport cut the time that people had to wait to receive treatment for their asthma? 2. Did the use of the passport lessen the time that people spent in A & E? 3. If the passport did lead to patients receiving their treatment more quickly than before, is there any evidence to say that this also had the effect of helping them to avoid being admitted for their asthma? 4. Or, did the opposite happen that is did the use of the passport and the ensuing quicker assessment/ treatment lead to people being admitted more quickly? 5. Is there any evidence to suggest that if people are more willing to go to A&E that this is having the effect of reducing potential deaths? 14 15 Results 15 patients signed up to the pilot. They were actively recruited from the severe difficult to manage asthma clinic. The patients have got to know each other over a period of time so they asked me for an APP, I didn’t need to approach them. This was part of regular clinical practice so there was no need for ethics and the CEM audit had already been registered. All of the patients are at Step 4/5- see appendix 5- and all of them had expressed a reluctance to go to ED. They come from different areas and as such use different EDs and throughout the pilot they presented to University College Hospital, Lewisham, Darenth Valley, Croydon University Hospital, St. Mary’s Paddington and GSTT. 7 patients used the APP a total of 15 times; 3 patients 3 times, 2 patients twice and another 2, once only. For the purposes of this report all patients have been allocated a number so as to ensure anonymity and to demonstrate that any quotes used later on are not cherry-picked from one or two patients. Only patient, Patient1, had attended GSTT in both study periods and she will be used as a case study later on in the write up. Selection of answers from the The Near Time Patient Experience Questionnaire of particular relevance. Clinical governance is in the process of accessing the wider results and so what is presented is the results of the 15 uses of the APP only. It needs to be made explicit that the reported experience is across a variety of different EDs in central London and beyond. See appendix 2 for the questionnaire. Presented below are the most pertinent questions bearing in mind what the patients had expressed regarding why they don’t go to ED when at high risk that is: they feel vulnerable they are afraid to use ED when they are least able to talk they are unable to say what they need they are asked the same questions many times they feel that they are not always listened to treatment isn’t always escalated as quickly as it needs to be. 4. Were you told how long you would have to wait to be examined? Question 4 No I was not told Yes and I waited as long as I was told Yes but the wait was shorter Grand Total Total 5 3 7 15 8. While you were in the ED, how much information about your condition was given to you? Question 8 I was not information Not enough Right amount Grand Total Total given any 1 1 13 15 16 9. Were you given enough privacy when discussing your condition or treatment? Question 9 No Yes always Yes sometime Grand Total Total 1 11 3 15 10. Were you as involved as you wanted to be in decisions about your care and treatment? Question 10 No Yes definitely Yes to some extent Grand Total Total 1 9 5 15 11. Were you asked to give details of your condition or illness more often than you thought necessary? Question 11 No Yes Grand Total Total 12 3 15 20. Overall, how would you rate the care you received in the ED? Question 20 Fair Good Very good Very poor Grand Total Total 1 4 9 1 15 Discussion- timeliness of treatment As previously mentioned, there was a control group and a study group and the College of Emergency Medicine audit tool was employed- as per appendix 3. Hundreds of hours of data were pulled and a statistician did this part of the analysis. She appreciated that we needed to look at a number of different areas. Firstly, she analysed how quickly the asthma patients that were having a severe attack, got various medicines as opposed to those that were not having a severe attack- as a measurement of best practice. The data-pullers had to have quite a sophisticated understanding of what constitutes mild, moderate, acute/ severe or life-threatening asthma, especially as our cohort of patients will sometimes present as moderate but then quickly deteriorate so that they have a severe or life-threatening attack. We decided that we would label the patients as either severe or non-severe to make the analysis easier. Secondly, the statistician looked to see if Ipratropium nebulisers had been administered. The administration of Ipratropium nebulisers is particularly pertinent here. This is because is it is only those patients that present with a moderate or severe/ life threatening asthma attack that require it in the emergency setting- see appendix 4. Some asthma patients will present to ED with a moderate asthma attack but then go on to, as one ED PDN expressed poignantly, “drop like a stone”. This is where the APP is particularly helpful because it avoids the ‘no-man’s-land’ of waiting 17 to be seen and knowing that at any minute the asthma may take a turn for the worse. Please refer to the Process Map on page 6. Secondly, the statistician drilled-down into the data to ascertain if those patients that were having a severe asthma attack and had got their medicines in a timely manner, had been managed as per ‘usual care’, or whether the Asthma Proforma had been used or whether the patient had an APP or both. We needed to know what was making a difference if a difference, that is an improvement, had been made. Thirdly, the statistician looked to see if the APP fastened their journey through ED. Finally, she examined whether the Asthma Proforma use had increased, decreased or stayed roughly the same across both data pulls because this could have had an influence on the results. Results Table 1: Rates of timely medication use, proforma use and average time spent in A&E in datasets 1 & 2 All patients Dataset 1 Dataset 2 p-value All Total 522 266 256 Proforma used 118(24.3) 65(28.0) 53(20.9) 0.066 B2 at all 356(96.0) 176(98.3) 180(93.8) 0.033 B2 in 10 minutes 136(57.4) 74(60.2) 62(54.4) 0.369 Steroids in 30 112(42.1) 55(46.6) 57(38.5) 0.184 mins Ipratropium at 202(63.3) 85(53.5) 117(73.1) <0.001 all Time in A&E 3.0(2.2-3.7) 2.8(2.0-3.6) 3.2(2.4-3.7) 0.001 (hrs)* Non-severe Total Proforma used B2 at all B2 in 10 minutes Steroids in 30 mins Ipratropium at all Time in A&E (hrs)* 263 75(29.2) 207(94.5) 65(49.2) 59(38.1) 121 38(32.8) 92(97.9) 33(54.1) 25(42.4) 142 37(26.2) 115(92.0) 32(84.1) 34(35.4) 0.253 0.074 0.301 0.386 103(58.9) 37(47.4) 66(68.0) 0.006 2.8(2.0-3.6) 2.7(1.9-3.5) 2.8(2.2-3.6) 0.069 77 14(18.2) 41(97.6) 20(76.9) 18(54.6) 0.008 0.999 0.891 0.777 39(97.5) <0.001 3.4(2.8-3.9) 0.184 Severe Total 140 63 Proforma used 38(27.1) 24(38.1) B2 at all 89(97.8) 48(98.0) B2 in 10 minutes 49(77.8) 29(78.4) Steroids in 30 40(56.3) 22(57.9) mins Ipratropium at 72(81.8) 33(68.8) all Time in A&E 3.3(2.6-3.9) 3(2.5-3.9) (hrs)* *displayed as median (interquartile range) 18 Table 2: Odds of receiving treatment n dataset 2 compared to dataset 1 adjusted for potential confounders All p-value Nonp-value Severe, OR p-value patients, severe, OR (95% CI) OR (95% (95% CI) CI) B2 in 10 0.92(0.480.805 0.93(0.44- 0.848 0.90(0.22- 0.885 minutes* 1.77) 1.98) 3.76) Steroids in 0.99(0.540.977 0.88(0.41- 0.747 1.16(0.40- 0.784 30 mins 1.82) 1.90) 3.40) Ipratropium 3.61(1.98<0.001 3.05(1.54- 0.001 19.67(2.25- 0.007 at all 6.60) 6.05) 171.69) Table 3: Visits by patients with a passport N(%) Total 9 Proforma used 2(22.2) B2 at all 9(100) B2 in 10 minutes* 5(62.5) Steroids in 30 5(55.6) mins Ipratropium at all 6(66.7) Time in A&E 3.4(2.9-3.9) (hrs)* *displayed as median (interquartile range) Table 4: Rates of timely medication use, proforma use and average time spent in A&E in datasets 1 & 2 Both datasets Dataset 1 Dataset 2 Total B2 at all No profor ma Profor ma Pvalu e No profor ma Profor ma Pval ue No profor ma Profor ma Pval ue 235(94 .0) 75(51. 4) 57(33. 5) 117(1 00) 60(66. 7) 55(57. 3) 0.00 4 0.02 1 <0.0 01 108(97 .3) 39(53. 4) 25(38. 5) 64(100 .0) 34(69. 4) 30(56. 6) 0.3 00 0.0 78 0.0 49 127(91 .4) 36(49. 3) 32(30. 5) 53(100 .0) 26(63. 4) 25(58. 2) 0.0 39 0.1 47 0.0 02 33(56. 9) 3.0(2.5 -3.6) 0.4 39 0.0 07 77(68. 8) 3.2(2.3 -3.6) 40(83. 3) 3.3(2.7 -3.8) 0.0 60 0.1 12 B2 in 10 minutes Steroids in 30 mins Ipratropi 127(60 73(68. 0.13 50(50. um at all .2) 9) 1 5) Time in 2.8(2.1 3.2(2. 0.00 2.6(1.8 A&E -3.6) 5-3.8) 7 -3.6) (hrs)* *displayed as median (interquartile range) 19 Case study demonstrating the benefits of the APP As previously mentioned, one patient, Patient 1 presented to GSTT ED in both data collection periods. This allowed the opportunity to do a case study. Patient 1 went to GSTT ED two times in the first study period and three times in the second study period. Her vital signs and peak expiratory flow recording show that she was always having a severe asthma attack as per British Thoracic Society (2012) guidance. On every occasion Patient 1 was admitted and on every occasion Patient 1 had intravenous (IV) Magnesium Sulphate administered. Within this context, IV Magnesium Sulphate is only given to patients that are having a severe or lifethreatening asthma attack and would usually be added on after back-to-back nebuliser therapy which includes Ipratropium 0.5 mg. So, having IV Magnesium Sulphate in this context can be used as a marker of severity of the asthma attack. The case study provides a fascinating insight into the benefit of both the Asthma Proforma and the Asthma Patient Passport in terms of how long it takes to get IV Magnesium Sulphate and how long the decision to admit takes. This will be given more attention later. What treatment Usual treatment Usual treatment 2/12/2011 73 minutes to Mg 163 minutes to decision to admit Asthma Patient Passport 18/01/2013 8 minutes to Mg Admitted but timing of decision not documented Asthma Proforma 8/02/2012 66 minutes to Mg 61 minutes to decision to admit 12/12/2012 42 minutes to Mg 68 minutes to decision to admit 29/11/2012 12 minutes to Mg 60 minutes decision to admit Positive clinician feedback The APP has been well received by ED staff and LAS staff. The clinician feedback section of the APP unanimously came back positive on all counts but unfortunately rarely informed as to what it was that was good or helpful. One written comment from an ED nurse was, “Having medication and treatment that works for the patient is helpful”. Fortunately, some of the patients were prescient enough to ask the clinicians to write down what they thought and various members of GSTT ED staff have fed back to me personally. LAS staff found it helpful in collecting the demographics and also in guiding treatment. Some of the patients do not wheeze and this can be confusing for healthcare staff. As reported by Patient 1 the doctors said, “This passport is a brilliant idea, everyone (with asthma) should have one … it’s so helpful having all the information there.” 20 “This is really useful- especially medication/ITU admissions and what to treat with.” Whilst I was seeing Patient 6 in the department a Registrar stated, “It’s good because if I had managed this patient by the guideline then she would have been discharged. So it’s good to have something that is individualised and easy to follow.” Hence, it seems that the APP does succeed in making it easier for healthcare staff because all the necessary information is in one place. There will be occasions when the most appropriate management of the individual’s asthma steps outside the national guideline and this is based on the patient’s experience and is signed off by the Asthma Professor. The clinicians will always have to ‘treat what they see’ and be guided by best practice guidelines, but if this can be made safer by, for example as with Patient 6, a higher threshold for safe discharge, this can only be a good thing. Evaluation So did the APP: 1. Save lives? 2. Improve the patient experience? 3. Make it easier for the healthcare professional/ staff? Saving lives is obviously difficult to prove but the fact that the patients did not put off going to ED when they needed to spoke volumes. From the clinician point of view timeliness of treatment is imperative. “It (the APP) really helps because it gives you all the information you need because let’s face it, time wasted is time closer to a tube.” (ED nurse) The tube she is referring to is ‘intubation’ and the need for ITU. Patient 2 has had many admissions to ITU that have needed intubation. Experience has taught him that a delay in getting IV Magnesium means that he will end up needing to be intubated. He says of the APP, “I wouldn’t go to Lewisham (ED) without it. It makes such a difference and stops me needing to go to ITU” In this sense, the APP has really helped with appropriate escalation of treatment and may have saved his life. 6/7 patients assure that having the APP “takes out the receptionist” and less time is wasted. It was pleasing to see the patients seeking help appropriately and the hope is that all patients with ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’ have access to their own APP. “I think it (the Asthma Patient Passport) is wonderful, I have used it many times and have found it invaluable on most admissions, especially on those not in my local, it saves me worrying about being able to speak, and gives more info that I don't have 21 the breath to give. All nurses and doctors I have shown it to feel it be used by patients with any long term condition, and it certainly works for us Brittles!!” (Patient 7) “As a result of my experience using the passport I no longer fear visiting A&E and the stress that usually accompanies it, which is generally caused by long waits, being ignored or being patronised. This in itself means I won't be putting my life at risk by avoiding going to A&E.” (Patient 3) Improving the patient experience was another important measure. We hoped that the APP would speak for the patient and therefore avoid needing to say the same thing over and again at a time when they are too breathless to complete a sentence. “It encouraged me to go to A&E because it cut down on questions and a lot of timefrom LAS through to the doctors.” (Patient 6) 12/15 stated that they were not asked too many questions; this was one of the primary objectives of the APP so this is a huge success. 1/15 felt that s/he was not given enough privacy when discussing his/ her condition or treatment. This was a shame and was something that had been alluded to before and a statement about the need to respect privacy and dignity had been incorporated into the APP. However, 14/15 did feel that their privacy and dignity was respected. 13/15 fed back that the overall care they received in ED was either good or very good. This is high praise indeed and given that these patients would normally put their lives at risk because they have such a terrible time in ED, it is nothing short of a miracle. 13/15 patients felt that they were given the right amount of information. 14/15 felt that they were involved in decision making. Making it easier for the healthcare professional/ staff was another anticipated benefit of the APP. This did turn out to be the case as described earlier with the clinicians’ feedback. However, this is a complex area and requires quite a lot of careful consideration. There was one occasion, when the APP failed to access more timely care and the patient was left waiting as outlined below: “My only suggestions are when you hand in your passport in that the receptionist hands it straight into the nurse or doctor and not asking u to sit and wait in the waiting room to be called when struggling to breath.” (Patient 4) This episode was disappointing and I needed to ask the PDNs and the Reception Manager for their help. Perhaps I should have spent more time with the ED receptionists and I was reminded that I had intended to find the study that looked at GP receptionists understanding of the nature of asthma. There was another occasion when a concerned member of ED staff fed back that an APP-user had become frustrated because care hadn’t been delivered as advised by the APP: the ED nurse believed that that the correct clinical decision had been made and that to do as requested would be to over-treat. Given that some preventable asthma deaths can be as a result of under or inappropriate treatment it was a relief to hear that so much thought had been given to the implications of over-treatment because it suggests 22 highly skilled clinical judgement which is appropriate. One of the anticipated benefits of the APP was that patients and healthcare staff would work together in partnership and to enhance good 2-way communication. This was achieved the majority of the time but the fact that this is not absolute is reassuring in the sense that ‘the good, the bad and the ugly’ has been represented. The Learning The learning is that the Asthma Patient Passport helps the patient with ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’, to have the right treatment, in the right place, at the right time. Right treatment There is strong evidence from the case study that using the APP accelerates the time that IV Magnesium is given. This isn’t always needed, as some of these patients will just need nebulised Ipratropium etc., but when it is needed it is critical and as mentioned, Patient 2 avoids intubation if he gets IV Magnesium in double-quick time. This is where the passport comes into its own and has the potential to save lives by making sure that treatment is escalated appropriately. The data informs that the use of Ipratropium nebuliser at GSTT ED has greatly improved since 2011-2012. It is likely that an added front sheet to the Asthma Proforma has encouraged this change in local practice. This will be a relief to the Step 4/5 asthma patients that go to GSTT ED as many of them talk about the benefits of Ipratropium in these circumstances. It is something that we have flagged-up with LAS and they have suggested that the latest version of the APP incorporates a pre-hospital treatment section- see page 15. Right place The average time spent in GSTT ED for those patients having a severe or lifethreatening asthma attack is 3 hours 20 minutes. This does not change when the APP is used. What does appear to change however is how quickly the decision is made that the patient needs to be admitted to hospital. This suggests that the APP does help the clinicians in their decision making but the simple fact is, is that the patient just isn’t well enough to be moved any earlier. Indeed on one episode, Patient 1 was reviewed 5 times over 3 hours 45 minutes before she was considered safe to go to the ward and this was with the proviso that the night team were made aware of her and if she were to feel any worse the emergency team would review. Patient 1 states that the APP “doesn’t see you getting of resus any quicker, but I would prefer them to be there watching me”. This takes us back to the Process Map where the patient is often left unobserved, alone and frightened- see pages 5/6. Right place need not be the resuscitation unit. Studying the ED cards revealed that it was sometimes appropriate that the patient went to Majors or even Minors instead. As the patients explained, this means that the APP is doing its job if the patients are presenting to ED in a timely manner because that means “we are not turning up at deaths door and therefore the APP saves lives” (Patient 5). Right time Admission avoidance and ED attendance are important indicators of control for the majority of people with asthma. This is more complex in people with ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’. This group of patients are fully medically optimised, are for the most part compliant, all have written asthma action plans and know how to escalate their treatment. There will be occasions when try as the will, their asthma will get the 23 better of them. For the majority of these patients admission is what is needed and should be encouraged because it keeps them safe. Again, the APP helps to save lives by ensuring that the users don’t ignore the severity of the asthma attack and gives them the confidence to access emergency care when they need it. Thus, the APP enables people to make the decision to go to ED at the right time. ED reception-staff play a very important role and one patient commented, “The APP triggered immediate action from the receptionist: I was in resus in less than 5 minutes.” (Patient 3) I realised only recently that my thinking had been very influenced by the concept of ‘timeliness of treatment and on the back of that had thought of the APP as a ‘Speedy Boarding Pass’. This is wrong thinking and the experiences of the APP users have born this out- this shouldn’t be about privilege. Our colleagues in ED are skilled clinicians but as the patients say, the APP “gives them a full picture of you in 30 seconds” and as such the APP can help with tightening-up the processing, so that the patient is given the right treatment, in the right place, at the right time. Summary The learning from asthma deaths will be revealed by the NRAD at some point in the future. As far as I am aware there is no other evidence that if people are more willing to go to ED that this will have the effect of reducing potential deaths, but this small scale study goes some way to supporting the idea. We know that patients with ‘severe difficult to manage asthma’ put themselves at risk because they are frightened to go to ED. Whilst it is appreciated that not all asthma deaths are in people at the more severe/ difficult end of asthma it may be that the APP could offer some hope to their peers. The APP has been welcomed by all: the patients, ED staff, LAS. Indeed, only last month LAS invited a patient and me to talk about the APP at their forum “An evening with us”. They are keen to work more closely with us and take the APP further and are exploring the logistics of taking such patients to the ED of their choice. Areas that will need further exploring in the next phase are: how soon IV Magnesium Sulphate is administered (in those patients that require it) evaluation of the pre-hospital treatment section Dissemination This has been a small pilot study. GSTT will continue with the APP and it is our aim to scale this up- shared wider this could help save lives and improve the experience of thousands of people with asthma and the attending staff. All of this for a relatively small cost. I speak for myself and on behalf of the patients when I say thank you to the LNNM/Florence Nightingale Foundation Partnership for making this possible. Asthma UK is keen to work with us on this and the SANN has also expressed an interest. The results of the study will be published in a peer reviewed journal and fed back to the asthma community and asthma patients. With the support of the LNNM/Florence Nightingale Foundation Partnership the APP has helped to save lives, has improved the patient experience and has made it easier for healthcare staff. “I have used my passport on several occasions, this has proved to be very helpful and had good feed back from the Doctors/ Consultants I showed it to at Croydon University Hospital. This has saved a lot of time having to repeat myself especially when I was out of breath and struggling to breath. I think more hospital should have this Passport scheme. Well done.” (Patient 4) 24 Appendix 1- first version of APP I HAVE SEVERE ASTHMA. I AM HAVING AN ASTHMA ATTACK AND NEED URGENT MEDICAL ASSISTANCE. I MAY NOT BE ABLE TO TALK/ANSWER YOUR QUESTIONS. (IF APPLICABLE: I DO NOT WHEEZE DURING ATTACKS) NAME: DOB: [Medicalert]: Address: GP: NAME ADDRESS N.O.K: Name & Relationship Telephone: Alternatively: Name & Relationship Telephone: 25 ALLERGIES: Medical: Food: Other: OTHER MEDICAL CONDITION CONSULTANT Prof. Corrigan, Respiratory Medicine & Allergy 5th Floor, Bermondsey Wing, Guys Hospital, London Specialist Asthma Nurse: Karen Newell Telephone: 02071 888636 MEDICATION Asthma (on this list include prn such as prednisolone) Other MY ASTHMA Best Peak Flow Lung function: FEV1 Usual Symptoms: (i.e. do you wheeze, quick attacks, peakflow going up and down) ASTHMA ACTION PLAN OVERVIEW From asthma action plan what would lead you to present at A&E with asthma if not having severe attack – i.e. persistent drop in peak flow coupled with being unresponsive to medication PREVIOUS HOSPITAL ADMISSIONS ITU: yes/no 26 HDU: yes/no Number of admissions to hospital this year: IF ADMITTED – ASTHMA ACTION PLAN i.e. is pain relief required – if so what is required? Dietary requirements – does dietician need to be informed? What medication has been effective when previously treated in an emergency (this is just an example that’s a personal one – everything will reflect individual’s experiences/needs) PREPARING FOR DISCHARGE: Information such as does the 24 hours free of nebulisers rule apply? Do you need to be discharged between certain hours/is it dangerous to discharge with certain weather (as a trigger)? Who is at home to care for the person/does someone need to be informed of discharged? PLEASE CONTACT ASTHMA TEAM IF FURTHER DETAILS ARE REQUIRED ON: number or bleep. SIGNED BY 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 Appendix 3 College of Emergency Medicine Standards for Asthma A) Life threatening asthma 1. Evidence in the notes that Oxygen was being given on arrival 2. Evidence in the notes that senior EM / ICU / PICU help was summoned if any life threatening features were present 3. Salbutamol 5mg or terbutaline 5 – 10mg + ipratropium 0.5mg by nebuliser or salbutamol 250 microgram (5 mcg/kg) intravenously given within 5 minutes of arrival in adults. Salbutamol 2.5mg or terbutaline 5mg + ipratropium 0.25mg given by spacer or nebuliser within 5 minutes of arrival in children 4. In 98% of cases documented evidence of pulse rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation measured on arrival 5. In 90% of cases pulse rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation repeated within 15 minutes arrival 6. CXR performed 7. IV hydrocortisone 100mg or oral prednisone 40-50mg given within 30 minutes of arrival in adults. IV hydrocortisone 100mg (50 mg if 2 – 5 years) or oral prednisone 30 - 40mg (20mg if 2 – 5 years) given within 30 minutes of arrival in children 8. In patient transferred to ITU / PICU they should be accompanied by suitable resuscitation and airway equipment and a doctor who is able to intubate the patient if necessary. B) Moderate / Severe asthma 1. Evidence in the notes that Oxygen was being given on arrival 2. Salbutamol 5mg or terbutaline 5 - 10mg given by nebuliser within 10 minutes of arrival in adults. Salbutamol 2.5mg or terbutaline 5mg by nebuliser or Beta2 agonist 2 – 10 puffs via spacer device given within 10 minutes of arrival in children 3. 98% documented evidence of peak flow, pulse rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation measured on arrival 4. 75% of cases peak flow, pulse rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation repeated within 1 hour of arrival 5. 90% of cases IV hydrocortisone 100mg or oral prednisone 30-50mg (20mg if 2 – 5 years) given within 30 minutes of arrival 36 6. 90% of discharged adult patients should have oral prednisolone 30 – 50mg for 5 days 7. 90% of discharged paediatric patients should have oral prednisolone 20mg (2 – 5 years) or 30 – 40 mg (over 5 years) for 3 days 8. 90% of cases GP or clinic follow-up arranged according to local policy for discharged patients. 37 Appendix 4 38 Appendix 5 39 References www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/guidelines/asthma-guidelines. 40