Elisabeth Hiller - Atlantic International University

advertisement

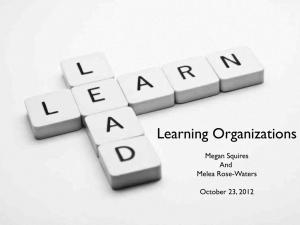

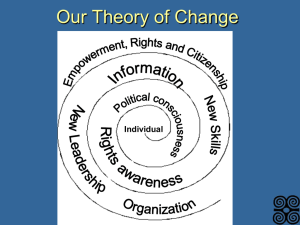

Elisabeth Hiller UD4023BBA9204 October 2007 Peter M. Senge: The Fifth Discipline An Assignment Presented to The Academic Department Of the School of Business and Economics In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For The Degree of the Doctor of Philosophy In Business Administration ATLANTIC INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page Contents Page Introduction 3 Summary 3 1 1.1 1.2 The five disciplines People perspective People encountering problems 4 4 5 2 General analysis and assessment 6 2.1 Structure 7 2.2 2.2.1 2.2.2 2.2.3 2.2.4 2.2.5 2.2.6 2.2.7 2.2.8 Part I Personal mastery Mental models Building shared visions Team learning Learning disabilities Systems versus individual thinking Options Conclusion 7 7 8 8 8 9 9 10 11 2.3 2.3.1 2.3.2 2.3.3 2.3.4 2.3.5 Part II Feedback The concept of feedback in systems thinking Nature loves balance Systems archetypes Conclusion 12 13 15 15 16 17 2.4 Parts III to V 17 2.5 2.5.1 2.5.2 2.5.3 2.5.4 2.5.5 2.5.6 2.5.7 2.5.8 2.5.9 More Critical assessment 17 Actualization 18 Creativity 19 Environment 19 Management 19 Leadership 20 Leaders 20 Team 21 Learning of team members 21 Social issues 22 Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 2 References 24 Introduction Peter Senge highlights in his book The Fifth Discipline that the sustainable competitive advantage derives from an organization`s ability to run faster than competitors. Companies need to get rid of their disabilities that threaten their effectiveness and efficiency. Modern technologies, free markets, and more competitors increase the pace of change. Finding out how to avoid dying, how to survive, and – at best – how to excel needs adaptive behaviour due to internal and external factors. Peter M. Senge, American scientist and director of the Center for Organizational Learning at the MIT Sloan School of Management, published his book `The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization` in 1990 and enriched it by about hundred pages of new experiences and interviews with managers in his 2006 revised edition. Summary Organizational learning requires knowledge about learning areas and the management of human resources. Both opportunities and limitations of organizational learning are introduced in this paper, focusing on Peter Senge`s book The Fifth Discipline. This book consists of five parts, all of which deal with possible effects of learning. The author emphasizes systems thinking and offers case studies to make the transformation from theory into practical experience understandable. The main focus of his work is the notion of a learning organization, adopting the perspective that companies are dynamical systems which need to permanently adapt and improve. He defines the learning organization as `organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together` (Senge, p.3). Creating competitive advantage depends on learning, both of the individual and the organisation. Senge often refers to the works of Harvard Professor Chris Argyris who established the types of learning `single loop learning` and `double loop learning`, the latter incorporating revisiting of the fundamental assumptions and thus dominating the former. Senge provides a framework of theory and suggestions of how to transform theory into practice to facilitate the process of organizational learning. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 3 1 The five disciplines In his book `The Fifth Discipline` Peter Senge states that the crucial competitive advantage to dominate the market is to learn faster than all rivals. Today`s networked organizations need the ability to adapt quickly to survive. Therefore, the process of learning needs to be implemented and transform a company into a learning organization. Senge offers a framework of five disciplines which need to be coped with at all hierarchical levels, these are 1. Systems thinking moving from seeing parts to seeing wholes 2. Personal mastery clarifying personal vision, focusing energy, seeing reality 3. Mental models understanding how internal pictures affect actions 4. Building shared vision transforming individual visions into shared vision 5. Team learning creating dialogue in turn as he puts it in his introduction. The author suggests that the five disciplines might just as well be called `leadership disciplines`. Leaders who excel in these disciplines will be the natural leaders of learning organizations. 1.1 People perspective First, Senge talks of `The Fifth Discipline` which is systems thinking, a discipline that fuses the four other learning disciplines to move from seeing parts to seeing wholes. He calls it `The Cornerstone of the Learning Organization` (Senge, p.55) and starts his inquiry by offering `[t]oday`s problems [to] come from yesterday`s `solutions`` (Senge, p.57), directing at answers may create questions. He claims that in complex human systems most managers – here he does not distinguish between leaders, the visionary persons, and managers, the operational actors – do not care for long-term achievements, but due to stakeholders, especially shareholders, they concentrate on short-term success, `… there are always many ways to make things look better in the short term` (Senge, p.60). Then he continues that this phenomenon ceases at `long-term dependency … it has its own name among system thinkers – it`s called `shifting the burden to the intervenor` … only to leave the system fundamentally weaker than before and more in need of further help` (Senge, p.61). An important law of `The Fifth Discipline` is not the integration of people into a system, as this would be an activity, but the knowledge that every person is part of the system. He states systems thinking to show `that there is no separate `other` …` (Senge, p.67) and the solution for problems to lie in the relationships with others. Consequently, systems thinking `is a framework for seeing interrelationships rather than things, for seeing patterns of change rather than static `snapshots`. It is a set of general principles …` (Senge, p.68). He emphasises systems thinking to be the `antidote to [the] sense of helplessness that many feel …` (Senge, p.69), a framework that supports recognizing structures which `underlie complex situations` (Senge, p.69). More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 4 Complexity theory suggests a permanent feedback process, as the whole system is in motion. All persons are `part of the feedback process, not standing apart from it` and thus a `shift in awareness` (Senge, p.77) occurs. People notice that they both are influenced and influence `reality` (Senge, p.78) – here he talks about the environment including persons. To communicate a language is needed, and `the feedback concept illuminates the limitations of our language` Senge complains (Senge, p.78) and suggests that the language needed should not be linear as cause and effect, but should meet the requirements of a dynamic complexity. `The systems archetypes provide that language. They can make explicit much of what otherwise is simply `management judgement`` (Senge, p.94). 1.2 People encountering problems Senge uses archetypes for shaping the cycles that systems go through. He found out two sorts of archetypes - `limits to growth` and `shifting the burden`. First, he explains reinforcing processes to produce both the desired results and `inadvertent secondary effects` (Senge, p.94) which may slow down the intended processes. His general advice here is not to push growth, but `remove the factors limiting growth` (Senge, p.95). Second, he observed the archetype `shifting the burden` to be addressed when problems are disguised or costly to master. Often `people `shift the burden` of their problem to other solutions – well-intentioned, easy fixes which seem extremely efficient. Unfortunately, the easier `solutions` only ameliorate the symptoms; they leave the underlying problem unaltered` (Senge, p.95) and so the problems remains, possibly grows, and the systems loses power as sources have been used without adding value to the organization. He suggests that solutions should address the fundamental causes, not only symptoms, to support long-term success instead of short-term benefits. To sum up, he recommends to control the systems archetypes to initiate an organization`s first steps `of putting the systems perspective into practice` (Senge, p.94). More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 5 2 General analysis and assessment Senge provides more than hundred pages of new outcomes deriving from interviews and other encounters with practitioners of a wide range of different companies. Complexity emerges in all kinds of society and business. Fragmenting problems into small pieces makes them manageable. But, Senge complains, people should see the big picture, not only the parts. Organizing and reassembling supports the process of searching for a complete picture, however, lots of people, managers included, give up before they reach the goal. In his book `The Fifth Discipline` Peter Senge provides a framework how to manage complexity and compares it to a three-legged stool which would not stand if any of the three legs were missing. Along with Deming he advocates the idea of a close connection between work and school in a sense that both the prevailing system of education needs to be transformed to transform the system of management, because they are both the same system (cf. Senge, p.xiii). But, Senge does not suggest how to change the prevailing educational system. Instead, he concentrates on changing the management system. `I call systems thinking the fifth discipline because it is the conceptual cornerstone that underlies all of the five learning disciplines of this book` (Senge, p.69) which are demonstrated in the box below: Box 2a More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 6 CORE LEARNING CAPABILITIES FOR TEAM ASPIRATION REFLECTIVE CONVERSATION UNDERSTANDING COMPLEXITY •PERSONAL MASTERY •MENTAL MODELS •SYSTEMS THINKING •SHARED VISION •DIALOGUE Concerning learning Senge includes all hierarchical levels when he states that the organizations `that will truly excel in the future will be the organizations that discover how to tap people`s commitment and capacity to learn at all levels in an organization` (Senge, p.4). He supposes organizations to be able to learn because they exist of human beings, and `[we] are all learners` (Senge, p.4) due to intrinsic curiosity and a natural love to learn. But, concerning organizational learning, hierarchy may foster or hinder learning. In case of an encouraging business atmosphere staff to innovate, invent, think about problems and solutions, an employee may feel well. But, if s/he feels the need to create and bridge a chasm for reasons of learning, s/he may be kept off by his direct leader who prohibits organizational learning, intentionally or not. So, tensions may occur. Basic disciplines need to be mastered, according to Senge, they are the features that distinguish traditional authoritarian organizations from modern learning companies. 2.1 Structure Senge divided his book into five parts. The first one is dedicated to the consideration that all people create their own reality, which means that people have the power and may control their future. The second part exclusively deals with the fifth discipline which is systems thinking and which Senge names the `cornerstone of the learning organization`. Here Senge provides technical aspects and tools needed for systems thinking, both for practical reasons and for systemic analysis. The third part highlights the four disciplines in a chapter for each topic. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 7 Part four offers reflections from practice. At last, part five suggests a sixth discipline where Senge discusses what lies ahead and follows the successful implementation of the fifth discipline. 2.2 Part I The first chapter introduces the idea of a `lever` according to the Greek mathematician Archimedes` (c.287-212 BC) words: `Give me a lever long enough … and single-handed I can move the world` to demonstrate that even small efforts may foster big improvements. Senge also explains the five disciplines of the learning organization with systems thinking as the fifth discipline fusing the other four into a unity of theory and practice. The suggested five disciplines are contrasted to familiar management disciplines such as accounting – the five disciplines differ because they are personal disciplines, which usually enhance the cruising radius of each learner. Traditional measurements such as benchmarking offer the opportunity to see chances, but may damage a learner`s creativity by copying and `playing catch-up` (Senge, p.11). The problem with benchmarking seems to be the ignorance of seeing the whole, because people focus on the nearer and thus foster piecemeal work. 2.2.1 Personal mastery Systems thinking, as Senge observed, is an intuitive trait of all people: when children play, they quickly learn systems thinking. Personal mastery as he uses it, `might suggest dominance over people or things` (Senge, p.7), but he uses the term for a special level or proficiency (dtto.). He regards personal mastery as the `spiritual foundation` (dtto.) of an organization, which occurs when a person continually strives for insight and is permanently clarifying his/her personal vision. This discipline of continuously deepening a person`s vision, focusing energies and developing patience and seeing reality as it is, enhances a company`s opportunities. Senge clarifies that personal mastery is an expression for a realistic view of the world and the willingness to break the rules if prevailing norms do not fit of pursuing the individually perceived reality. Senge suggests that personal mastery `is the bedrock for developing shared visions` (Senge, p.197). He stresses that people with high levels of personal mastery demonstrate more commitment, pursue more activities and have a deeper responsibility for their job. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 8 2.2.2 Mental models Mental models are deeply rooted modes of thinking, assumptions, generalizations, and imaginations how a person understands the world and how s/he takes action to shape the world. Perceptions are shaped by mental models, in the words of psychologists `people observe selectively` which means that they due to their personal history, professional education, experiences, etc. see the reality from their individual standpoint, and thus neglect other aspects. Management theory knows that changes can be introduced after recognition of the problem and by bridging the chasm which occurs according to the newly defined goals. Kurt Lewin suggested that `great cultural changes may be seen as processes in which social beliefs become unfrozen for a period, and then refrozen. … Later the freeze-unfreeze-refreeze concept became a foundation for explaining changes in a wide range of social and cultural circumstances`.1 An example of using mental models to trigger creative solutions was the scenario technique by the Shell company in the early 1970s. By thinking about future scenarios the individual scope is enhanced which in turn extends the organization`s opportunities. Henry explains `[c]reativity, learning and development … [to take] far greater prominence` (Henry, 2002, p.31). A method to recognize how individual mental models work, is the `left-hand column`, firstly introduced by Chris Argyris and his companions: the right-hand column jots down what is said, and the left-hand column is used for what the person thinks. This technique allows using thoughts as a resource that supports the individual reflection. 2.2.3 Building shared visions Senge suggests that `people excel and learn, not because they are told to, but because they want to` (Senge, p.9) if there is an energizing vision. Leaders need to create an inspiring vision that attracts staff, and in case they command a vision they will fail. Belbin 2.2.4 Team learning Senge reveals that individual IQs may top a team`s IQ, and vice versa, a team with an average IQ may expand its IQ enormously. Team learning starts with dialogues, which means that ideas are shared, assumptions are uttered, and a group think emerges. Today, in modern societies, he states, this kind of `thinking together` has vanished. `The discipline of dialogue also involves learning how to recognize the patterns of interaction in teams that undermine learning` (Senge, p.10), because if unnoticed, they erode learning. Senge diagnoses that teams are the unit where learning happens, in contrast to the individual. Thus, as a consequence, if teams are able to learn, organizations can learn. Learning is suggested as a life-long stadium that never ends. Quite the contrary, `[t]he more you learn, the more acutely aware you become of your ignorance` (Senge, p.10). 1 http://leaderswedeserve.wordpress.com/category/kurt-lewin/ 03 October 2007 More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 9 2.2.5 Learning disabilities The reasons why organizations learn poorly derives from the way people were trained to learn and to consume information. The kind of thinking was determined, too, and thus learning disabilities emerged. Senge suggests that even committed staff is prone to disabilities. The learning disabilities which often cause organizational failures are: `I am in my position` failure = focus on own position only `The enemy is out there` failure = others need to be blamed `The illusion of taking charge` failure = proactiveness is disguised reactiveness `The fixation on events` failure = short-term events prevent generative learning `The parable of the boiled frog` failure = slow, gradual changes endanger survival `The delusion of learning from experience` failure = mistakes often not experienced ´The myth of the management team` failure = solutions are praised, questions not The problem he detects when employees `focus only on their position, they have little sense of responsibility for the results produced when all positions interact` (Senge, p.19). If gaps between plans and results occur, or when things go wrong, people often seek to blame someone or something. This `the enemy is out there` syndrome is according to Senge `a byproduct of `I am my position`and the nonsystemic ways of looking at the world that it fosters` (Senge, p.19). Managers who take responsibility often react to problems. According to Senge, `proactiveness is reactiveness in disguise` and `[t]rue proactiveness comes from seeing how we contribute to our own problems` (Senge, p.21). Regarding experience, Senge suggests that the most powerful learning stems from direct and personal experience. Concerning management teams, Aryris reveals that they `break down under pressure` (quoted in Senge, p.25) and usually are able to exist in routines only. The five disciplines work as `antidotes to the learning disabilities`, but first the disabilities must be revealed (Senge, p.26). 2.2.6 System versus individual thinking Senge provides the beer game, a management game, which is designed to establish three groups of participants – a retailer, a wholesaler, and the marketing director of a brewery – all of whom act independently. The most important outcome is that any participant provokes reactions of the others, and the typical `manage your position` perspective neglects interaction with others, and they create a `vicious cycle`. Retailer, wholesaler or marketing director are able to intervene and to improve performance of all, there it is necessary to redefine the scope of influence. In the end, there is awareness that in many systems a single participant can succeed only, if other participants succeed, too. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 10 Box 2.2.6a The beer game – people learn that they need to see the wholes The teams blame each other Flaws occur elsewhere, so they do not learn Gradual actions make people oversee the big picture When they get proactive now, they worsen the situation When problems arise, people search for sth. or so. to blame. People do not see the consequences of their actions, because they `become their position` Box 2.2.6b More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 11 The beer game – lessons learnt (after Senge, p.40) Structure influences behaviour 1 Different people in the same structure tend to produce similar results Systems often cause their own crises Structure in human systems is subtle 2 Structure includes human decision-making – the operating policies translate perceptions, goals, rules and norms into actions Leverage often comes from new ways of thinking 3 Creating instability derives from ignoring how decisions affect others 2.2.7 Options Systems theory teaches that managers need to look beyond individual failures and mistakes. The underlying structures which facilitate errors and flaws need to be scrutinized. Systemic structure, as Senge defines, `is concerned with the key interrelationships that influence behavior over time` (Senge, p.44). The roles people adopt voluntarily or under constrain, shape the persons` behavior. To exemplify, he cites the well-known experiment performed by the psychologist Zimbardo in 1973, where students were divided into prisoners and guards in a mock prison. After a few days it turned out that prisoners behaved as prisoners and guards as guards, and in the end the experiment had to be ceased as the psychic stress overwhelmed the participants. Box 2.2.7a More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 12 The systems perspective (after Senge, p.52) SYSTEMIC STRUCTURE (GENERATIVE) PATTERNS OF BEHAVIOR (RESPONSIVE) EVENTS (REACTIVE) Event explanations deal with the question `who did what to whom` (Senge, p.52) and are currently the most common ones. Thus, reactive managerial activities dominate. Patterns of behaviour, however, aim at `longer-term trends` and `begin to break the grip of short-term reactiveness` (Senge, p.52). The systemic structure is the least common and most powerful level. The question `what causes the patterns of behaviour` needs to be answered. As Senge reveals, realization of both problem and hope for improvement trigger insight of all participants. In case of prevailing event-thinking, generative learning can hardly emerge. A framework of systemic thinking needs to be introduced. 2.2.8 Conclusion Systems thinking is a conceptual framework based on system dynamics. Senge suggests a practical recipe to transform theory into business life. His most exciting ideas are that seeing interrelationships need to be detected instead of cause-and-effect chains, and that recognizing processes of change leads to a holistic view instead of a series of snapshots. Instead of learning each discipline one by one, Senge suggests to develop all five ones `as an ensemble` (p.11). Integrating new tools he states to be much harder than using them separately. The aim is to fuse them into a `coherent body of theory and practice` (p.12). By now, systems thinking seems to dominate the other disciplines, but Senge explains the other four ones to be necessary to `realize its potential` (p.12). Individuals perceive their environment and themselves and thus offer an opportunity to `shift of mind` (Senge, p.12). The Greek word `metanoia` indicates a radical shift or change, which lies within the learning process itself. Turning back and taking action is connected with learning today – formerly it occurred as a passive treatment, usually in classrooms. Adaptive learning is important, too, but it needs to More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 13 be enhanced and joined by generative learning to increase both a person`s and an organization`s capacity. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 14 2.3 Part II Senge devoted part two of his book to the fifth discipline, systems thinking, which acts as the cornerstone of the learning organization. Senge formulated laws of the systems thinking – they are shown in the box below. The discussions focuses on technical terms, especially stressing `feedback`. Box 2.3a The laws of the fifth discipline (after Senge, pp.57-67) 1 Today`s problems come from yesterday`s `solutions`. 2 The harder you push, the harder the system pushes back. 3 Behavior grows better before it grows worse. 4 The easy way out usually leads back in. 5 The cure can be worse than the disease. 6 Faster is slower. 7 Cause and effect are not closely related in time and space. 8 Small changes can produce big results – but the areas of highes leverage are often the least obvious. 9 You can have your cake and eat it too – but not at once. 10 Dividing an elephant in half does not produce two small elephants. 11 There is no blame. (1) Solutions that do not erase the flaw but relocate the problem within the system, do not actually add value to the organization. Instead, the problem remains undetected because the roots for it are not deleted. (2) Systems thinking knows the term `compensating feedback` which catches managers when numbers of products or services decline and they enforce their efforts in marketing to make the customer buy. (3) Many human systems generate the illusion to make things look better in the short run instead of caring for high quality and long-term achievements. (4) Problems are often adjusted to familiar solutions instead of finding new solutions to new problems. (5) Accepting or supporting short-term solutions leads to longterm dependency, a phenomenon which systems thinker call `shifting the burden to the intervenor`. At worst, the system is left weaker than before and is more dependent than ever. (6) All natural systems accommodate an optimal rate of growth, which is `far less than the fastest possible growth` (Senge, p.62). In case the system is accelerated too much, it will slow down by itself for compensation. (7) There is `a fundamental mismatch between the nature of reality in complex systems and our predominant ways of thinking about that reality` (Senge, p.63) which means that the roots for misfortune or failure do not lie close together. Complex systems often do not allow recognition of a tight relationship between cause and effect. (8) As obvious solutions often do not work, systems thinking is attacked. Instead, small but More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 15 significant solutions sometimes provoke extraordinary and enduring improvements. Thus, systems thinking calls this phenomenon `leverage` (Senge, p.64). Considering processes instead of `snapshots` (Senge, p.65) illuminates a chain of changes, whereas considering snapshots only highlight single actions. (9) Choices a manager needs to take, often occur as dilemma, e.g. quality or quantity, or centralisation or decentralisation. Thus, a stasis emerges, as the manager decides for one of the two offers. If s/he regarded both of them as acceptable, improvements that really add value to the company could be made. (10) `Living systems have integrity` (Senge, p.66) and require to see the whole instead of parts of it only. Selective perception usually allows recognizing some pieces of the big picture. (11) Everybody is part of a systems, so in case of failures, when there is a tendency to blame others, systems thinking declares that there is no `other`, and instead, the solution needs to be found within the individual `enemy` (cf. Senge, p.67). 2.3.1 Feedback Senge starts the practice of systems thinking with understanding the `feedback concept` that demonstrates how actions can reinforce or counteract each other. Complex systems usually overwhelms participants of the system with information, and consequently some persons within the systems suffer an information overkill. Systems thinking offers a set of principles rather than single `snapshots`. It is a discipline that underlies complex systems and empowers system thinkers to recognize structures. By seeing wholes `we learn how to foster health. To do so, systems thinking offers a language that begins by restructuring how we think` (Senge, p.69). Senge uses the most `poignant example` of the need for systems thinking to demonstrate that there is permanent action and reaction. The following boxes show straight lines which clarify cause and effect, and the cycle of aggression clearly indicates what cause provokes an effect. Both diagrams do not relate to other factors that might trigger powerful activities. Box 2.3.1a More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 16 Straight lines of aggression (after Senge, pp.70-1) TERRORIST ATTACKS US MILITARY ACTIVITY THREAT TO AMERICANS NEED TO RESPOND MILITARILY PERCEIVED AGGRESSIVENESS OF US TERRORIST RECRUITS Box 2.3.1b More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 17 Aggression cycle (after Senge, pp. 70-1) TERRORIST ATTACKS TERRORIST RECRUITS THREAT TO AMERICANS PERCEIVED AGGRESSIVENESS OF US NEED TO RESPOND MILITARILY US MILITARY ACTIVITY A `perpetual cycle of aggression` (Senge, p.71) is shown above. The reason for failing to foresee military aggressive activities lies in two kinds of complexity – detail complexity, and – more difficult – dynamic complexity. `Conventional forecasting, planning, and analysis methods are not equipped to deal with dynamic complexity` (Senge, p.71). Thus, if organizations understand both detail and dynamic complexity, they can manage it. Simulations therefore need to be equipped with facts that allow determining dynamics. A shift of mind therefore is needed: Box 2.3.1c More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 18 Shift of mind (after Senge, p.73) FROM TO linear cause-effect chains interrelationships snapshots processes of change More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 19 2.3.2 The concept of feedback in systems thinking In practice, systems thinking uses the concept of `feedback` to understand how activities can cause or counteract each other. Structures that repeatedly emerge are the basis for learning. Straight lines like shown above limit people`s imagination as system thinkers. Instead, the theory suggests that `every influence is both cause and effect` (Senge, p.75). All persons are part of the feedback process, they do not stand apart from it. This knowledge usually cares for a shift in awareness. The systemic view of feedback assumes `everyone [to share] responsibility for problems generated by a system` (Senge, p.78). Consequently, knowing that not all persons execute the same power of leverage to balance the system, people will not waste time to search for a scapegoat. Additionally, the concept of feedback exposes the need for adequate language. 2.3.3 `Nature loves balance`2 Both reinforcing and balancing feedback processes, and delays make up the systemic feedback perspective. Reinforcing means amplifying feedback support growth, both positive growth and negative growth. In contrast, balancing or stabilizing feedback loops work when there is goal-orientation. Not moving goals trigger balancing feedback to move slowly. In case the goal is moving, the balancing feedback will move at maximum speed as the goal does, but feedback will not accelerate to be faster than the goal. Additionally, a lot of feedback processes contain delays that interrupt `the flow of influence which make the consequences of actions occur gradually` (Senge, p.79). Managing delays can foster stability and avoid breakdown. As systems thinking aims at long-term perspective, the recognition and management of feedback is important. Some feedback loops may be neglected in the short term, but they will return in the long run. To sum up, reinforcing and balancing feedback as well as delays are building blocks for `systems archetypes`. 2 Senge, The Fifth Discipline, 2006 p.84 More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 20 2.3.4 Systems archetypes The systems perspective can be transformed into practice, if both archetypes are mastered. Box 2.3.4a Archetype I – limits to growth (after Senge, pp.94-103) 1 Reinforcing processes are initiated to generate desired results. 2 Both a spiral of success and inadvertent secondary effects are created. 3 Secondary effects may slow down the success. e nag Ma rin nt p me le cip DON`T PUSH GROWTH; REMOVE THE FACTORS LIMITING GROWTH. At first the reinforcing process needs to be identified – the improvements and the activities that lead to the improvements. Then the `shifting the burden` structure needs to be scrutinized. This problem occurs in three steps, namely the gradual worsening of the problem, a worsening of the health of the system, and a emotional situation of helplessness. Box 2.3.4b More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 21 Archetype II – shifting the burden (after Senge, pp.103-112) M rin nt p e gem ana 1 An underlying problem generates symptoms that need attention. 2 The problem is difficult to address, because it is obscure or costly. 3 People shift the burdens. 4 The quick fixes ameliorate the symptoms, the problem remains. 5 The problem grows worse and weakens the system. le cip CREATE LONG-TERM SOLUTIONS THAT RESPOND TO THE PROBLEM. 2.3.5 Conclusion The linear way of thinking should be left. As relationships are usually not linear, and feedback loops clarify about causality and original sources, the systemic perspective can be adopted. The technical aspects and the tools of systems thinking are introduced to facilitate the transformation of theory into practice. Part II goes beyond conceptualization of part I and accompanies the reader into systems analysis. 2.4 Parts III to V Parts III, IV and V support the theory of the first two parts. Part III deals with the building blocks of transforming a company into a learning organization: the core disciplines personal mastery, mental models, shared vision, and team learning are reviewed and linked to systems theory. Part IV provides reflections from practice. Part V gives a short outlook of the future, focusing on the `Gaia` hypothesis which is `the theory that the biosphere, all life on earth, is itself a living organism` (Senge, p.382) and that all new that happens deals with the whole. All parts III to V are not essential for understanding Senge`s main message, they just support the contents of the first two parts. 2.5 Critical assessment Systems thinking is a concept that is based on the assumption that parts of a systems act differently after being isolated from the system. Systems thinking examines how the system itself and parts of the system interact, and how the components of the system influence the system. Systems dynamics is an area of systems theory and tries to understand the behavior of complex systems. It considers internal feedback loops and time delays that influence the More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 22 system. Another part of systems theory is chaos theory, which is mostly used in mathematics and physics. It describes the behaviour of nonlinear dynamical systems which due to specific circumstances show dynamics due to initial conditions. Chaotic behaviour occurs in nature as well as in laboratories, weather and climate are examples of natural chaos. Before chaos theory was introduced, the prevailing system theory could not explain observed behavior of some experiments. The emergence of the personal computer provided opportunities to use mathematics for describing non-linear behavior. A dynamical system can be classified as chaotic, if it meets certain features: if it is sensitive to initial conditions, if it is topologically mixing, and if its periodic orbits are dense. Many scientific fields of research use chaos theory, e.g. finance, biology or psychology. Catastrophe theory, too, is a part of dynamical systems, and detects that bifurcation points are prone to appear as geometrical systems. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 23 2.5.1 Actualization Learning organizations are challenging to create. Using Senge`s terms systems thinking, personal mastery, mental models building shared vision, and team learning, there is evidence that creating the five disciplines is costly and hard to achieve. Establishing communication networks, building relationships and dealing with conflicts are some of the areas companies should put in motion to develop into a learning organization. The focus in Senge`s The Fifth Discipline is on business organizations, but society needs to adapt, too, and thus there is a need to systems thinking. The types of organizational change are either radical or incremental, as Henry (2002, p.39) suggests: RADICAL INCREMENTAL -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Procedures Re-engineering Quality improvement People Self-organization Learning organization Due to individual feelings that usually deal with anxiety und uncertainty, incremental changes are to be preferred to radical `tortures`. Mintzberg (1976) stresses the importance of both left and right hemisphere, with the left providing `linear, sequential and verbal thinking` and the right supporting `spatial, visual and relational thinking` (quoted in Henry, 2002, p.53). Along with Senge, Mintzberg highlights holistic perspectives instead of single views. Box 2.5.1a Modes of thinking related to planning and managing (quoted in Henry, 2002, p.53) Analysis Perception Linear Simultaneous Sequential Relational Explicit Implicit Simple steps Complex Clear Ambiguous Certain Uncertain Known novel More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 24 2.5.2 Creativity Due to quick changes of business environments, organizations need to develop conceptions of how to exploit staff`s explicit and implicit knowledge. Henry discovered all people to be creative, but they will not be recognized as such `unless their idea is accepted by their field`s judges and opinion makers` (Henry, 2002, p.17). Thus organizations need to nurture creative networks. She suggests to develop a strategy to extend the characteristics of creative persons, these traits are `positivity, playfulness, passion, and persistence` (dtto., p.18). There is a need to distinguish between creative management and managing innovation: creative management `is linked with with transforming organizations and managing innovation is linked with new product development` (Henry, 2002, p.23) 2.5.3 Environment Capra states that organizations `need to undergo fundamental changes, both in order to adapt to the new business environment and to become ecologically sustainable` (Capra, 2002, p.86). In some respect organizational climate affects creativity at work and the environment can `dramatically affect` motivation. According to Ekvall (1991, 1997) the capacity for innovation depends on freedom, trust, commitment and diversity (quoted in Henry, 2002). Challenges that need to be encountered may occur as `wicked problems` as Rittel (1972) stated (quoted in Henry, Managing Problems Creatively, 2004) that cannot easily be recognized, in contrast to soft problems that can clearly be identified. Networking with others is essential to today`s modern world interactive connectivity. Capra stated that [o]ne of the key insights of the systems approach has been the realization that the network is a pattern that is common to all life. Wherever we see life, we see networks` (Capra, 2002, p.8). The function of parts of the network is to `transform or replace other components, so that the entire network continually generates itself` (Capra, 2002, p.8). The criterion to distinguish living from non-living systems is expressed by the term `autopoiesis`, introduced by biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela. Their concept combines both physical boundary and the metabolic network. Both human society and business environment can be characterized as an autopoetic system as life should be understood as a whole (Capra, 2002, p.9). 2.5.4 Management Senge utters the machine metaphor to be so powerful `that it shapes the character of most organizations` (quoted in Capra, 2002, p.91). But, as Capra signals, if a company is seen as a living being, it must be realized `that it is capable of regenerating itself and that it will naturally change and evolve`(Capra, 2002, p. 91).The management role can be examined by using the `contingency view`, an approach that segments management into many different functions and activities, and then searches how they can be balanced, taking into consideration that managers have to deal with a wide array of issues. Krantz and Maltz (1997) suggest to separate the `role as given`, which is the role as defined by the role influencers, and the `role as taken`, which relates to the job holder as s/he considers the scope of actions (OU, Integrating Practice, Learning and Theory, p.15). Mintzberg (1973) distinguishes between ten working roles for senior managers and classified More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 25 them into three groups which are the interpersonal roles – figurehead, leader and motivator, liaison, informational roles – monitor, disseminator, spokesperson, and decisional roles – entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator, negotiator. The most important thing a manager needs to do, after Mintzberg (1994), is to act: `The manager who only communicates or only conceives never gets anything done, while the manager who only `does`ends up doing it all along`. Thus, there is a necessity to involve the team. 2.5.5 Leadership Daniel Goleman (1998) provided ground-breaking work on `emotional intelligence` which is not a single discipline but a bundle of concepts. The components are `self-awareness, selfregulation, motivation, empathy, social skill` (Goleman, quoted in Henry, 2002, p.24) and can be developed over time, requiring `a programme of individualized training over a long period` (Henry, 2002, p.25). Therefore, as long-term developmental programmes are costly, organizations firstly should recognize a need, and secondly, they should be willing to pay for it, as it can be assumed that in contrast to courses on detailed technical know-how success will not occur immediately, but over time. Leadership shapes the individual business atmosphere which can be `visionary`, `entrepreneurial`, or transformational` according to Westley and Mintzberg (1991), quoted in Henry (2002). They suggest the transformational style to employ salient capacities of sagacity, foresight, insight, and inspiration – all development happens incrementally. Clearly focusing on revitalization of the organization, they interact with people and shape the mental models of others, aiming at commitment of staff. After action, evaluation of outcomes is a means of assessing effectiveness and efficiency. A fundamental attribution bias is the tendency to accept all good outcomes to the own person, and all the bad outcomes to external factors. For reasons of self-esteem this trait can be helpful, but, it hinders, or at least reduces learning and taking corrective action. Another aspect considers the control of events and environment. Usually, people tend to believe to have greater control than reality reflects. Fenton-O`Creevy et al. (2003) suggest the risks of a person`s decisions and actions are likely to be underestimated and therefore problems in learning from experience occur. The crucial difference between a living system and a machine is that a machine can be controlled, `a living system, according to the systemic understanding of life, can only be disturbed` (Capra, 2002, p.98). Therefore, companies need to accept that they may influence staff by `giving impulses rather than instructions` (Capra, 2002, p.98). 2.5.6 Leaders Seeking for maximizing profits, `it is crucial for managers and business leaders to understand the interplay between the organization`s formal, designed structures and its informal, selfgenerating networks` (Capra, 2002, p.96). Thus, the managers have an active role in creating the future and they therefore need to build a bridge between the concept or idea, and staff. Feeling environmental changes and being able to respond, is central to leadership – the pure accounting, directing and commanding is not enough. `[I]nterpersonal skills need to be developed, and perceptual and attitudinal skills, too, as Henry (2002) suggests. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 26 Senge highlights the importance of mental models and broad perspectives offered by systems thinking as well as the ability of seeing things from different perspectives – along with him, Kanter introduces the metaphor of a `kaleidoscope` which is `a device for seeing patterns`. Kanter defines kaleidoscope thinking to take `an existing array of data, phenomena, or assumptions and being able to twist them, shake them, look at them upside down or from another angle or from a new direction – thus permitting an entirely new pattern and consequent set of actions` (quoted in Henry, 2002). More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 27 So both systems thinking and kaleidoscope thinking embrace the process of learning, aiming at creating managers sensitive to their environment. Isenberg (1987) suggests managers to use intuition in at least five ways (cf. Henry, 2002, p.55): To sense when a problem exists To perform well-learned patterns rapidly To synthesize isolated dat To use `gut feeling`to check results arrived at rationally To by-pass in-depth analysis all of which focus more on the rationality than on sensitivity. But, Isenberg is aware of a manager`s skills to listen and to develop intuition. Simon (1988) talks of intuition to be no `mysterious talent`, but `a speedy form of recognition` (quoted in Henry, 2002, p.56). Avoiding risks is a trait that many mangers employ. Both fear factor. i.e. how much the potential outcome threatens a person, and control factor, i.e. how much a person is in control of events, are components of risk perception. On the one hand people usually behave risk averse in case they consider potential gains, but on the other hand, people tend towards risks to avoid losses (cf. OU, Themes and Theories, p.36). Kahneman and Tversky (1979) suggested `prospect theory` to introduce the combination of risk and loss aversion depending on a personal reference point due to individual feeling of being in loss or in gain, and this point may change over time. Prospect theory explains that as people are loss averse, they avoid risks above their individual reference point and seek risks below. The willingness to take or avoid risks shapes managerial behavior and may lead to biases according the individual mental map, or, in Senge`s terms `mental model`. Further limits of rationality embrace many options to be filtered out before a formal analysis is performed, and the same data to lead to different conclusions according to decision-makers. Individual ethics shape decision-making as well. 2.5.7 Team According to Henry (2002) an `effective creative team will contain a mix of characters`. Different types of personality are important because they offer a wider range of possibilities how to master a problem and increase `the chance of cross-fertilization of ideas, albeit at the expense of some tension when the inevitable differences arise` (Henry, 2002, p.33-4). The `glue that holds the modern workforce together is common values` according to Kanter (1997, quoted in Henry, 2002, p.36) – an insight that supports Senge`s shared vision. All changes organizations need often trigger anxiousness and feeling uneasy of staff. Creative and innovative organizations `display a capacity to accept ambiguity and uncertainty` as Stacy argues (1996, quoted in Henry, 2002). 2.5.8 Learning of team members More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 28 The importance of active learning is highlighted by Knowles (1975) who advocates the type of self-directed learning, but acknowledges that most people have not learnt how to learn. Self-directed learning includes learning objectives, learning resources and strategies, evidence of accomplishment, and criteria and means of validating. However, as Brookfield (1985) mentioned, if the outcomes of learning is not defined, measurement criteria cannot be identified at start. According to Jarvis (1992, p.11), learning `is the essence of everyday living and of conscious experience; it is the process of transforming that experience into knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, and beliefs`. Learners may encounter five learning gaps, as Light and Cox (2001, p.47) identified: a gap between recall and understanding, a gap between understanding and ability or skills, a gap between ability or skills and actually wanting to use them, a gap between wanting to use abilities or skills and actually doing so, and a gap between actually using abilities or skills and changing. However, barriers to learning may occur. Mumford (1988, p.26) provides a list of hinderers which are perceptual, cultural, emotional, motivational, cognitive, intellectual, expressive, situational, physical, and due to specific environment. Reflection as re-examination of experience is the core of learning and development. Boud et al. (1985) offer a framework that comprises three stages in turn: returning to experience, attending to feelings, at last reevaluating experience. Asking friends for help is another source of a reflective learner, as Moon (1999) stated. Structured reflection according to Johns (1994, p.73) provides questions as the most important part of self-directed learning. Grant (1996) stresses the importance of a knowledge-based theory of the firm, arguing that firms exist because they better integrate and apply specialized knowledge than the markets. The intersection of strategy and HR issues occur in the fields dealing with knowledge, leadership, and the learning of organizations. 5.2.9 Social issues Both economic and psychological views acknowledge that people are prone to `bounded rationality`, a concept introduced by Simon (1957) focusing on the limitations of cognitive and information-processing capacity. Tetlock (1991) characterizes human decision-making by creating three groups: People as naive economists – the rational perspective People as naive psychologists - the psychological perspective People as naive politicians – the social perspective This classification is useful in the field of accounting and finance. Tetlock focuses on rational judgements and does not include the social perspective and individual behavior. Where people work, there is a need to accept and respect them, so even in the business area of finance social communities need to be taken into consideration. Utility theory is based on rationality and More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 29 `describes all decision outcomes (financial and otherwise) in terms of the utility (or value) placed on them by individuals` (OU, Themes and Theories, 2006, p.23). Bazerman (2001, pp.3-4)) advocates utility theory and describes formal decision-making processes based on rational considerations. Formal rationality is an approach to understand economy. But, there is evidence, that understanding decision-making of people supports the assessment of future market behaviours, e.g. in the field of finance. So the limitations of the rational-economic view trigger examination of social behavior. The Hidden Connections by Capra (2002, pp. 61-67) reveal his goal to provide a systemic framework for the understanding of biological and social phenomena. The nature of living systems which he called the `pattern perspective`, the `structure perspective` and the `process perspective` which integrates them. Additonally, Capra introduces a fourth perspective, the `meaning`. He suggests that the perspectives are fundamentally interconnected and share equal importance. The systemic perspective was the result of Talcott Parsons` integration of structuralism and functionalism into a unified framework, highlighting that people`s activities are both goals-oriented and constrained, as Capra explains. The relevance of Capra`s insights affect managerial thinking in relation to people management as there is evidence today that dealing with people should be considered as non-linear and highly complex. There is no recipe for handling persons, staff, or managers. But, as Capra suggests, there are an extremely wide range of factors that affect behaviour and results. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 30 References Bazerman, M. (1998), Judgement in Managerial Decision Making, New York, John Wiley. Boud, D., Keogh, R. and Walker, D (1985), Promoting reflection in learning: a model in D. Boud, R. Keogh and D. Walker (eds) Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning, London, Kogan Page. Brookfield, S. (1985), Self-directed learning: A critical review of research in S. Brookfield (ed.) Self-directed learning: From Theory to Practice. New Directions for Continuing Education, no. 25, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. Capra, F. (2002), The Hidden Connections, Flamingo, An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, 77-85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB. Fenton-O`Creevy, M., Nicholson, N., Soane, E. and Willman, P. (2003), Trading on illusions: Unrealistic perceptions of control and trading performance`, Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 76, pp.53-68. Grant, R.M. (1996), Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (Winter Special Issue): 108-122. Henry, J. (2002), Creativity and Perception in Management, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, ISBN 0 7619 6825 3 (pbk). Henry, J. (2004), Managing Problems Creatively, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, ISBN 0 7492 9579 1. Jarvis, P. (1992), Paradoxes of Learning: On Becoming an Individual in Society, San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. Johns, C. (1994), Nuances of reflection, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 3, pp.71-5. Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979), Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk, Econometrica, 47, pp. 263-91. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 31 Knowles, M. (1975), Self-directed Learning: A Guide for Learners and Teachers, New York, Association Press. Light, G. and Cox, R. (2001), Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: The Reflective Professional, London, Paul Chapman Publishing. Mintzberg, H. (1973), The Nature of Managerial Work, New York, NY, Harper & Row. Mintzberg, H. (1994), Rounding out the manager`s job, Sloan Management Review, 36, pp.11-27. Moon, J.A. (1999), Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice, London, Kogan Page. Mumford, A. (1988), Learning to learn and management self-development in Pedler, Burgoyne and Boydell (eds) op. cit. Open University (OU) (2006), B830 Integrating Practice, Learning and Theory, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, 2nd edn. Open University (OU) (2006), B830 Themes and Theories, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, 2nd edn. Senge, P.M. (2006), The Fifth Discipline, Doubleday, Random House, Inc., ISBN 0-38551782-3. Simon, H. (1957), Models of Man, New York, Wiley. Tetlock, P.E. (1991), An alternative metaphor in the study of judgement and choice: people as politicians, Theory andPsychology, 1 (4), pp.451-75. More Publications | Press Room – AIU news | Testimonials | Home Page 32