Erie Doctrine Explained: Swift, Erie, and Modern Application

advertisement

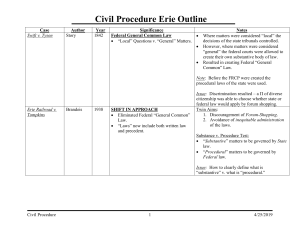

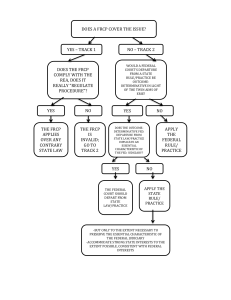

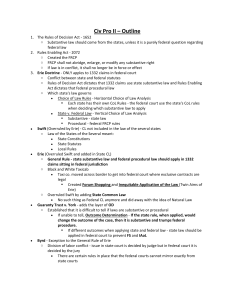

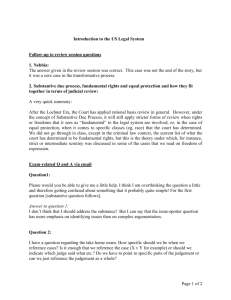

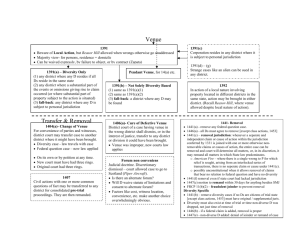

Erie doctrine Swift v. Tyson (1842) held that the rules of decision act (originally passed in 1789 and codified in 28 USC 1652) should only apply to state statutory law. That is, the US Supreme Court held that the language "the laws of the several states . . . shall be regarded as ther ules of decision in civil actions in the courts of the US" for cases in diversity meant that only state statutory law applied. when the outcome of the case was based on case (judge-made) law, the federal judges would apply federal common law. This was part of a grand experiment to reveal the natural law of the universe (the brooding omnipresence) throught he court system and to encourage uniformity of decisions in the states as well with the assumption that state judges would begin to follow federal precendet. The experiment was clearly a failure by 1938. There was no hint that law was becoming uniform throughout the states, and the Swift decision had led to abuse in the form of forum shopping and inequitable application of laws. An example of this can be seen in Black and White Taxi v. Brown and Yellow Taxi. Both parties were originally corporations under Kentucky law. The two parties had a contract dispute that Kentucky law would clearly find in favor of B&W. Therefore, B&Y reincorporated in Tennessee and then rbought a diversity suit in federal court, where the federal common law was applied and B&Y was victorious. Furthermore, scholarly investigations had shown that the legislative intent of the Congress in passing the RDA was that both statutory and decisional law would apply to federal court's sitting in diversity. These considerations were taken into account when the US Supreme Court decided Erie v. tomkins. The court held that the federal common law had led to discrimination against parties due to the rampant forum shopping (as done by B&Y) and by inequitable application of laws. Moreover, it held that the creation of legal principles out of thin air by federal judges in the name of a mythical federal common law had arrogated to the judges legislative power which the Constitution prohited. Theredore, Erie held that in cases sitting in diversity, the state decisional and statutory law of the state in which the district court was located would apply. As usual, a decision that radically changes things led to problems that needed to be sorted out. The main issue was the difference between substantive and procedural. Since Erie declared that state substantive law must always be applied in courts sitting in diversity, where did one draw the line? Guaranty v. York was the first case to address this issue. In this case, York brought a federal diversity suit against Guaranty. Guaranty argued that York's suit was barred by the state statute of limitations and therefore should be barred from being heard at all. York argued that the statute of limitations was merely a procedural issue and so a federal equity court could still give him relief. The justices held that since a federal court in diversity is essentially a state court (as it applies all state laws) the outcome of a suit in federal court must be substantially the same as it would have been in a state court. This is known as the outcome determinative test. Therefore, as York's claim was barred by the state statute of limitations, he had no right to bring the suit in a diversity court. This was not the last word, however. In Byrd v. Blue Ridge, the US Supreme Court held that a even where the outcome would be changed, a federal rule could apply when there were "affirmative countervailing considerations." In this case, a state held that a certain proceeding was to be held in front of a judge rather than a jury. Because the right to trial by jury is a fundamental right granted by the 7th Amendment to the US Constitution and codified in the FRCP 38, state substantive law could not be allowed to trump the procedural aspect of the federal courts because the right to jury trial was held to be more important than a state law. This decision was seconded by Hanna v. Plumer. The issue was whether a service of summons should be done by the method presecribed by state law or federal rules of procedure. The court held that FRCP are based on the Constitution and therefore can rarely be breached. The history is this: Article III, section 1 permits Congress to create the federal courts, while Article I, section 8 (necessary and proper clause) permits Congress to make whatever laws it sees fit. The FRCP were created as a result of the Rules enabling Act, codified in 28 USC 2072. This law permitted the US Supreme Court to enact the prescribe the rules that became the FRCP. Moreover, these rules were created and then analyzed by the finest legal minds in the nation before they were enacted by Congress. The Rules Enabling Act further states that the rules shall not "abridge, enlarge, or modify any substantive right" and that any laws in conflict with the rules will no longer have force. In Hanna the court held that because the service of process affected nothing other than the way in which service was made, the federal rules applied. That is, the rules did not fail the outcome determinitive test, and there were "affirmative countervailing considerations" militating for the application of the federal rule, namely that the rules were enacted by the constitutional power of the US Congress. Another way to look at all this is with the pertinent and valid test created by the court in Stewart v. Ricoh. The court held that so long as any rule of the FRCP is broad enough ot be pertinent to the matter under consideration it should apply if it is valid. Validity goes back to the Rules Enabling Act, in that it is valid so long as it does not "abridge, enlarge, or modifiy the substantive rights" of any litigant. As long as the Federal Rule is arguably procedural, it will not violate the pertinent and valid test. Becaue of the pedigree of the rules discussed supra, it seems nearly impossible that a Federal Rule will ever be found to be invalid.