Reports_files/Workshop Report_final_final

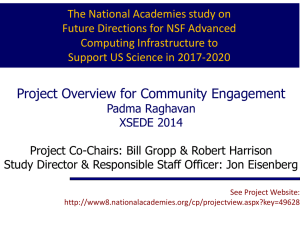

advertisement