Human Resource Development Strategy

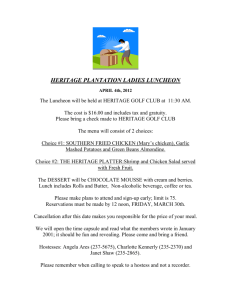

advertisement