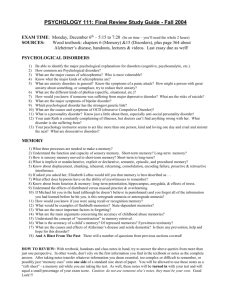

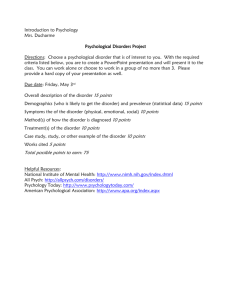

Psychological Disorders Chapter 15 Word Document

advertisement