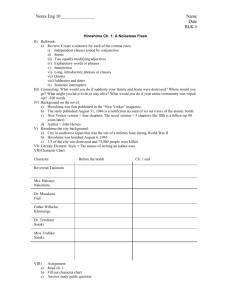

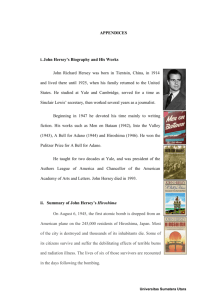

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION

advertisement