Executive Summary

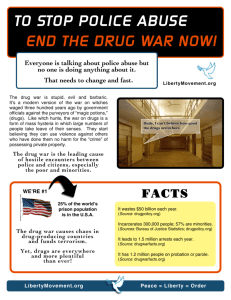

advertisement