Goldsmith Workshop summary report5

advertisement

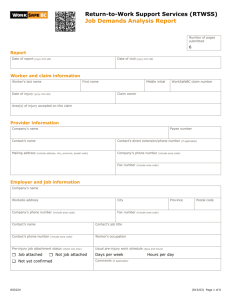

Line Manager Behaviour and Return-to-work Workshop summary report: Research exploring line manager behaviours in facilitating successful return-to-work of employees on long-term sick leave due to anxiety and depression, back pain, heart disease or cancer Introduction to project Sickness absence costs employers approximately £11 billion per year i with long term sickness absence contributing up to 75% of absence costs ii. There is an urgent need to improve the effectiveness of returning employees to work, particularly following long-term sickness. Much of the responsibility for supporting employees’ return-to-work falls on line managers who, in turn, are likely to look for guidance from Human Resource (HR) and Occupational Health (OH) professionals. However, little is known about the behaviours/competencies managers need in order to facilitate a successful return-to-work. To address this, the research team from Goldsmiths, University of London has been commissioned by the British Occupational Health Research Foundation, with the support of the Chartered Institute of Personnel Development, the Health and Safety Executive and Healthy Working Lives to examine the line manager’s role in the return-to-work process. The aim is to produce guidance that will help to improve organisations’ and line managers’ effectiveness at facilitating employee return-to-work. This report provides a summary of the first stage in this research: a series of workshops with HR and OH professionals. Method The research team conducted five workshops for HR and OH professionals iii. A total of 78 OH professionals and 64 HR professionals attended the workshops to explore a range of issues relating to employee return-to-work, following long-term sickness absence. The principal questions explored were: what line manager behaviours facilitate employee returnto-work following long term sickness absence due to anxiety and depression, back pain, heart disease or cancer; and what behaviours represent barriers to employee return-to-work following the same health conditions. To elicit the line manager behaviours, participants were asked to draw from their own experiences of employees who had returned to work following a period of long term sickness absence due to anxiety and depression, back pain, heart disease or cancer, either successfully or unsuccessfully. With each case they were asked to note the positive and negative behaviours the manager had demonstrated throughout the process. These behaviours were discussed within groups and common themes were extracted from case studies. In addition to discussing line manager behaviour, workshop delegates were also asked to discuss a number of current issues facing Occupational Health and Human Resource professionals. The data from these discussions are currently being analysed and will be published in due course. Findings In total there were 57 themes identified after all the data had been collated. While this figure is high, many of the themes, although titled differently, had similarities. The most commonly reported themes are summarised below and examples of positive and negative behaviours as well as the number of groups reporting each theme are provided in Table 1 and information on each theme is as follows. Data from one group could not be used as no specific examples of line manager behaviours from case studies were recorded. Themes: Communication - Communication appeared to be the emerging dominant theme and one group stated this to be the most important factor in the return-to-work process. The participants suggested that if the manager communicates with the employee at an early stage of their sickness absence and then regularly throughout it, the return-to-work is more likely to be successful. It was agreed that there is a need for good communication between the manager and OH and HR whilst the employee is absent or returning to work. Emotional and practical support - Participants suggested that as the employee is returning to work, the manager must show both emotional and practical support. If the manager exhibits consideration, empathy and a genuine interest in the well being of the employee, then they are more likely to feel valued and so return to work successfully. In addition to this, it was suggested that the manager should work with OH and HR to plan the return-to-work process and accommodate practical support such as a phased return-to-work, a buddy system or allowing time off to see physiotherapists and counsellors. Flexibility - Linked closely to practical support is the need for the manager to be flexible in their approach to the returning employee. They must be willing to consider alternative roles and temporary adaptations to the employee’s job during their rehabilitation into the workplace. Manager’s knowledge - The manager’s knowledge of the return-to-work process and of the employee’s condition was considered important. Where the manager could draw upon past experience of the return-to-work process following long term sickness absence, they were able to deal more efficiently with the returning employee. Where the return-to-work was unsuccessful, it was identified that the manager had initially failed to understand and spot the presenting symptoms of the employee’s illness and then lacked the knowledge to obtain help from other professionals whilst the employee was returning to work. Manager and employee relationship - The pre-existing relationship between the manager and the employee was highlighted as playing a role in the return-to-work process. If the manager has a good relationship with the employee before the long term sickness absence, then they are more likely to trust them and so accommodate their needs whilst they are returning to work. Referral – Finally, the timing of the referral to OH has an impact on the success of the returnto-work process. If the employee is referred quickly to OH in the initial stages of their illness or subsequent long term absence then they are more likely to return-to-work successfully later on. Table 1: Summary of common themes Theme Communication Emotional support Practical support Flexible Knowledge Manager and employee relationship Referral Examples of positive manager behaviour Examples of negative manager behaviour -Maintained contact with employee throughout absence -Good communication between the manager and OH/HR -Early communication and then kept in regular contact with the employee -Regular contact by telephone and home visits -Considerate -Sympathetic on the return-to-work -Making employee feel valued -Showed concern, interest and empathy -Respect for confidentiality of employee -Manager struggled with difficult conversations -Manager did not contact the employee for a long time -Manager did not tell anyone that the employee was off sick -Frightened and avoided contact -Manager supported OH and HR involvement through the phased return -Allowed the employee release to go to counselling sessions (6 in total) -Encouraged the employee to try a phased return-to-work. Met with HR and employee and all agreed the phased return -Introduced a buddy system -Supported physio sessions- costs and time off -No empathic behaviour following return-towork -Withdrawn due to fear -Cynical towards employee -Hostile towards employee -Mistrust of employee and sarcastic -Manager exclude OH and external health professionals in case-load meetings -Manager did not accept the OH or GP advice regarding staff fitness to work -Didn’t discuss possible rehab plans- no attempt to get the person back to work even if they took up lighter duties -Failed to cover parts of the workload while the employee was absent -Manager reduced the targets for the employee so they were under less stress -Flexible and willing to consider roles and temporary adaptations -Allowed employee to continue to work as it was her wish -Experiences of the process in the past gave the manager more confidence -Manager sorted out all of the paper work for the employee -Professionalism -Unwilling to accommodate recommendations by OH even on a temporary basis -Manager focussed on what the employee couldn’t do rather than what they could do -Lack of flexibility and reluctance to consider phased return and required changes -Manager misread anxiety about job as anxiety about back injury -Lack of knowledge, understanding and value of the different parties involved -Line manager did not spot that stress was causing the presenting illness -Good relationship with the member of staff -The manager originally cared and trusted the employee -Employee and manager trusted each other and so were happy with the decisions made -Early referral and involvement of OH -OH referral by the second week -Blame the employee and state that they are unable to cope with reasonable requests -Poor understanding and distrust of the employee, unable to accept diagnosis and responsibilities -Late referral to OH -Taking too long to refer to treatment No. groups reporting (out of 24) 23 13 13 10 9 7 5 Next stages for the research The preliminary data collected from the workshops will form the foundations of the research. However, it is important to note that the themes were developed from the perspectives of OH and HR professionals only. Therefore, to build on this information, the views of managers and employees who have direct experience of the return-to-work process need to be established. In April/ May 2009 telephone interviews will be conducted with managers who have dealt with employees on long term sickness absence due to anxiety and depression, back pain, heart disease or cancer and employees returning to work after a long term sickness absence due to the same health conditions. In June/July a questionnaire study will be conducted with both managers and employees. Together these three studies will provide valuable information on the effective and ineffective line manager behaviours associated with return to work following long term sickness absence. Once complete, this research aims to develop guidance material for Occupational Health and Human Resource professionals, and line managers to help manage the return to work of employees. For further information or to participate in the next stage of this research please contact Ben Hicks at b.hicks@gold.ac.uk or on 07881 915 776. Alternatively, visit the website: http://homepages.gold.ac.uk/pss01bh. Department of Health (2004) ‘Choosing health: making healthier choices easier.’ London: DH Unum Limited, Institute for Employment Studies (2001), ‘Towards a better understanding of sickness absence costs.’ Dorking: Unum iii The workshops were held at the HSE (23/2/9 for OH), the CIPD (24/2/9 FOR HR), Loughborough University (26/2/9 for OH) and Healthy Working Lives (13/3/9 OH and HR). i ii