North American Industry Classification System–1997

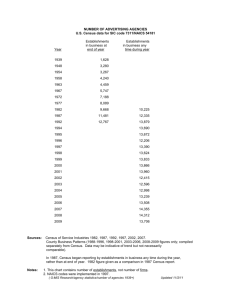

advertisement